* Your assessment is very important for improving the workof artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download - Sacramento - California State University

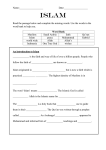

Muslim world wikipedia , lookup

Satanic Verses wikipedia , lookup

The Jewel of Medina wikipedia , lookup

Islamic terrorism wikipedia , lookup

International reactions to Fitna wikipedia , lookup

Islamic democracy wikipedia , lookup

Islam and Mormonism wikipedia , lookup

Salafi jihadism wikipedia , lookup

Islamofascism wikipedia , lookup

Islamic–Jewish relations wikipedia , lookup

Criticism of Islamism wikipedia , lookup

Political aspects of Islam wikipedia , lookup

Islam in Egypt wikipedia , lookup

Islam and secularism wikipedia , lookup

Morality in Islam wikipedia , lookup

Islam and Sikhism wikipedia , lookup

Soviet Orientalist studies in Islam wikipedia , lookup

Islamic missionary activity wikipedia , lookup

War against Islam wikipedia , lookup

Islamic extremism in the 20th-century Egypt wikipedia , lookup

Schools of Islamic theology wikipedia , lookup

Islam in Somalia wikipedia , lookup

Islam and war wikipedia , lookup

Islam and violence wikipedia , lookup

Islam and modernity wikipedia , lookup

Hindu–Islamic relations wikipedia , lookup

Islamic schools and branches wikipedia , lookup