* Your assessment is very important for improving the work of artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download Part_I_Philo - CLSU Open University

Survey

Document related concepts

Transcript

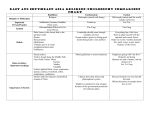

Unit I Philosophy: The Foundation of Knowledge Meaning of Philosophy The word philosophy can be looked at from two aspects: its etymological and its conceptual definition. Etymologically, philosophy comes from the Greek words, philos and sofia, which mean love of wisdom. Thus, a philosopher is a lover of wisdom. Stated briefly, philosophy is a search of meaning. The word “search” means to look, to find, to seek. It connotes, however, something more serious, more intense, more of a quest. There is definitely a world of difference between the ordinary and the philosophical meaning of search. The difference lies in the three elements found in a philosophical search. These are: 1. The object of the search is of real value to the subject. In philosophy, broadly speaking, “object” refers to a thing, “subject” to the person philosophizing. 2. It “consumes” the whole person – his attention, concentration, interest, effort. 3. It is continued without let-up until (a) the answer is found, or (b) the answer is not yet found, but the conviction is reached that for the moment at least, this is the best possible although still imperfect answer. One observes that a human being can never be satisfied, completely and for always. True, for being a homo viator, a traveller, and life presents a lot of questions. Philosophy can answer most, but not all, of these questions. However, this should not be a cause of despair. Accepting one’s life as it is – a finite, imperfect being – is accepting also the inadequate answers to certain questions. It is enough that one tries hard up to life’s end to confront the myriad problems of being a homo viator in this world. Conceptually, philosophy is the rational and critical inquiry into basic principles. Philosophy is often divided into four main branches: metaphysics, the investigation of ultimate reality; epistemology, the study of the origins, validity, and limits of knowledge; ethics, the study of the nature of morality and judgment; and aesthetics, the study of the nature of beauty in the fine arts. 2 The Nature of Philosophy It is in the very nature of philosophy that man searches for the meaning of himself and his world. It can truly be said that philosophy was born the very first time man started wondering at what he saw around him. As used originally by the ancient Greeks, the term philosophy meant the pursuit of knowledge for its own sake. Philosophy comprises all areas of speculative thought and includes the arts, sciences, and religion. As special methods and principles were developed in the various areas of knowledge, each area acquired its own philosophical aspect, giving rise to the philosophy of art, of science, of religion, and every endeavour which individuals undertake (e.g. institutional philosophy, philosophy of development). The term philosophy is often used popularly to mean a set of basic values and attitudes toward life, nature, and society - thus the phrase “philosophy of life.” Because the lines of distinction between the various areas of knowledge are flexible and subject to change, the definition of the term philosophy remains a subject of controversy. To the early philosophers, they looked with favour ”…on a total world picture, in the unity of all truths – whether they are scientific, ethical, religious, or aesthetic.” A Greek philosophos was concerned not only with particular types of knowledge, but with all types. Later, of course, subjects like mathematics, physics, chemistry, biology, psychology, astronomy, theology – come into their own. An individual with advance knowledge of philosophy has adequate understanding of the following: 1. 2. 3. 4. Logic (the science and art of correct thinking). Ethics (the science of the morality of human acts) Epistemology (the theory of knowledge, the goal of which is truth) Metaphysics (the foundation subject of all philosophy, it deals with human reality and system of human thought that seeks to explain the fundamental concepts of man) 5. Cosmology (the study of inanimate things such as the universe, from the philosophical viewpoint) 6. Aesthetics (the study of the beautiful) 7. Rational or Philosophical Psychology (the study of life principle of living things, specifically that of man) 8. Theodicy (the philosophical study of God). 9. Social Philosophy (the study of man in relation to the family, the State, and the Church) 10. Philosophy of Man (is the inquiry into man and his dimension as person and as existent being in the world: his dignity, truth, freedom justice, love death, and his relations with others and with God. 3 The Three Roles of Philosophy Each philosophical movement can be said to be an answer to a crisis situation. The history of philosophy shows that philosophers are quick to grasp, examine, reflect, criticize, and comment on current movements and events. 1. The Role of Krisis One has to look at the economic and political scenery and do some critical reflection which is, after all, “the special role of philosophy in a crisis situation.” a. “Crisis” comes from the Greek word krisis, which means “the act or power of distinguishing, of separating, of distinguishing” the good from the bad, not just concentrating on the bad alone. Examples are critiques are the reviews on newspapers and journals: of musical concerts, of paintings and sculptures, and of books. 2. The Role of Poesis Poesis is a creative role. The philosopher interpreter must dare to say which has been unsaid to transform and lift up his experience. Language is the medium that philosopher uses as critic and as interpreter. Interpretation is actually what all philosophers have done, interpreting the world as they see it, interpreting the other philosophers in the past as well as their contemporaries, as archaeologists do their discovered stones, bones and parchments. 3. The Role of Phronesis Aristotle defines phronesis as a “sort of practical wisdom, a certain capacity to think and feel in the situation as befits a man of action,” thus an individual “dapat matutong makiramdam, ayon sa damdamin.” In phronesis the individual tries look at and assess himself, can look around and find out what makes the community impoverished, determine what factors led to the nation to become a basket case in the region, and what made powerful countries impose their will to less developed nations. This means one has to look at the three dimensions of time: the past, perhaps not so far back as Magellan’s and Legaspi’s voyages but, to something more recent like Ninoy’s struggles against the dictatorship, to see how his untimely death has espoused new concepts (people power, civil society and plunder) that reshaped our nation’s traditions. The past have affected our present, and how we can transform this present to a “better future world,” is determined by actions which are founded on sound institutional philosophies. 4 Importance of Philosophies in the Development of Human Beings Various philosophies have been anchored on the individual’s innate desire to know and understand the reasons of existence, the nature of truth, reality, knowledge, and relationship with environment and society. Philosophy is a search for meaning and the quest for truth - objectives needed by every human being to secure for him a full, meaningful, and satisfying existence. Thus, it can be said that everyone is a “philosopher” by force of necessity. Every social institution–culture, government, economic system, religions, and the family have philosophical roots. Philosophical beliefs, in many historical instances, had influenced the overthrow of regimes; the changing of old economic systems, and the introduction of new ones, because people held certain paramount views and values to influence and guide their beliefs on to what extent should political institutions and economic systems rule and affect their lives. The best argument why philosophy is the concern of all is that, as the “matrix of all knowledge”, it affords wisdom about the totality and essence of the human being, the nature and purpose of the universe, and God. It also provides the necessary answers about how individuals achieve good morality and happy lives - the ideal manifestations of a good and civilized society. Through philosophy, the fundamental questions about the nature of things and the ends of life are also being addressed; thus, people will become practical and productive elements of their communities or social groups. As the early Greeks would say: a man who refuses to have his own philosophy will have the “characteristics of a brute beast, and be left to his own instincts.” Many people used to think and still believe that philosophy is concerned with long formulations of concepts, and study of complicated contradictions from the diverse views of known philosophers. But take away philosophy from one’s life and the individual is mindless of the significant issues of today, like political killings and bureaucratic corruption, the culture of impunity and that people will seem unaffected. They tolerate these events because they don’t want to understand them as these problems do not directly affect them. Philosophy is the “why” and the “how” of things of any phenomenon, which must be considered first when we are tracing the roots of all problems or issues. In a country where its leader is faced with a myriad of economic, political, and institutional problems, the people search for answers and ask for accountable governance from the head of government. In the Philippines, perhaps, what we need, like Plato had prescribed, is not an actor acting as a politician, is not a businessman posing as politician, and is not an opportunist masquerading as president, but should have one who is a philosopher. 5 But a human being is always influenced by his or her own ideas or by someone’s idea even if at times, it is contrary to himself/herself. Is there some truth, therefore, to the popular joke that if you marry a nagger, you will gradually become a philosopher?” What if the issues of a nagging spouse are about vices and immorality, infidelity, immaturity or sexual incompatibility? Do you really need philosophy to contend with such issues? Philosophy, therefore, is the concern of all human beings. It is not just the mastery of complicated philosophical methodologies, or the adequate knowledge of experimental science or pure theology that must necessitate one in the study of the individual; rather philosophy must start with common sense. What takes a person to be philosopher is: the mind that the Almighty gave him and the true love of wisdom to know the ultimate truth. Philosophers and the Origin of “Philosophical Concepts and Isms” Is philosophy obsolete in our present scientific and modern technological age? Francis Bacon (1561-1626), English philosopher and statesman and one of the pioneers of modern scientific thought, declared that “Science gives us power.” Science is a branch of knowledge that deals with a body of facts or truths systematically arranged and showing the application of general laws. The sciences, either natural or social sciences, study physical and social phenomena which enable human beings to exercise control and mastery of nature, and in the process, use this knowledge to create or produce things either constructively or destructively (e.g., discovery of medicines, guns and the atomic bomb.) However, according to the American scholar and author Mortimer Adler (1902-2001), in his famous book “The Difference of Man and the Difference It Makes (1967)”, science itself is not morally neutral, that is indifferent to the value of the ends for which the means are used; it is totally unable to give human beings any moral direction for it affords them no knowledge whatsoever of the order of goods and the hierarchy of ends. Philosophy, therefore according to Adler, teaches man the difference between right or wrong and directs him to the good deeds that befit his nature, Philosophy should be uppermost in any culture or civilization. The more science humanity possesses, the more man needs philosophy, because the more power he has, the more he needs direction. The utility or application of philosophy is moral or directive, in while science, particularly natural or modern science, the utility or application is technical or productive. While science provides man with the means he can use, philosophy directs him to the moral ends he should seek. 6 Socrates (469-399 BC), Socrates was a Greek philosopher who profoundly affected Western philosophy through his influence on Plato. Born in Athens, the son of Sophroniscus, a sculptor, and Phaenarete, a midwife, he received the regular elementary education in literature, music, and gymnastics. Socrates believed in the superiority of argument over writing and therefore spent the greater part of his mature life in the marketplace and public places of Athens, engaging in dialogue and argument with anyone who would listen or who would submit to interrogation. Socrates was reportedly unattractive in appearance and short of stature but was extremely hardy and self-controlled. He enjoyed life immensely and achieved social popularity because of his ready wit and a keen sense of humor that was completely devoid of satire or cynicism. His teachings were 1. That an individual should not be concerned with self or property, but with improvement of his soul through the pursuit of wisdom and truth. Only through wisdom would lead to right living; and that only evil could result from ignorance: an individual must depend on reason as guide in the attainment of good life. 2. That the unexamined life is not worth living. The highest virtue is knowledge of what is good and do the good. No one knowingly does evil. Only through knowledge of the true nature of a person, gained by examining what is good and what is not good for will enable an individual to achieve happiness (Rinder, 1995). Plato (428?-347 BC) Plato, the footnote to all forms of knowledge, was born to an aristocratic family in Athens. His father, Ariston, was believed to have descended from the early kings of Athens. Perictione, his mother, was distantly related to the 6thcentury BC lawmaker Solon. His father died when Plato was a child and his mother married Pyrilampes, an associate of the statesman Pericles. As a young man Plato had political ambitions, but was disillusioned by the political leadership in Athens. He was a follower Socrates’ basic philosophy and dialectical style of debate: the pursuit of truth through questions, answers, and additional questions. Plato witnessed the death of Socrates at the hands of the Athenian democracy in 399 BC. Fearing for his own safety, he left Athens temporarily and travelled to Italy, Sicily, and Egypt. In 387, Plato founded the Academy in Athens, the institution often described as the first European university because it provided a comprehensive curriculum, including such subjects as astronomy, biology, mathematics, political theory, and philosophy. Aristotle was the Academy’s most prominent student. 7 Plato’s Knowledge, Reality, and Psyche For Plato, true knowledge may be attained only through the power of reason, and that the knowledge must be something that is permanent. According to him, only the unchanging and unchangeable things of the world have true reality. He classified two kinds of realities: the reality of physical objects known by the senses and the true reality of the realm of abstract – eternally true, pure ideas and concepts knowable by reason (Plato considered this as the higher reality). Happiness, Morality and on the Absolute To Plato (as well as to Socrates and Aristotle) attaining happiness is the highest good for man; it is his ultimate purpose, and primary goal in one’s existence. However, Plato viewed happiness not as a life of continuous physical pleasure, but as being a result of virtuous and moral behaviour. Plato taught that there is an absolute standard of morality, that a moral life is governed by reason in accordance with virtue. Plato saw the “morality of the soul” as a balanced life, that is, reason ruled and maintained the proper balance and harmony among the elements of man’s psyche. Plato envisioned the Idea of the Good, upon which the universe is founded; which is also the absolute source of all that is right and beautiful in the universe; and the origin of all reason, value, truth and reality. Plato also believed the concepts of the immorality of the soul and its reincarnation. (H. Rinder, 1995). Aristotle Aristotle (384-322 BC) was a Greek philosopher and scientist, one who shares with Plato and Socrates the distinction of being the most famous of ancient philosophers. Aristotle’s philosophy is distinguished from Socrates and Plato by his use of empirical or deductive reasoning. Empiricism, in philosophy, is a doctrine that affirms that all knowledge is based on experience, and denies the possibility of spontaneous ideas or a priori thought (a priori is a term used to denote the kind of knowledge derived from intellect or reason). Until the 20th century the term empiricism was applied to the view held chiefly by the English philosophers of the 17th, 18th, and 19th centuries. Of these the English philosopher John Locke was the first to give it systematic expression, although his compatriot, the philosopher Francis Bacon, had anticipated some of its characteristic conclusions. His works are divided into three categories: popular writings, memoranda, and treaties. His memoranda 8 were great collections of research materials and historical records prepared with help from his students when he taught at the Lyceum, the school he founded. He viewed morality as a state in which reason controls a person’s irrational desires and appetites so that he or she expresses acceptable behaviour. Unlike Socrates, Aristotle believed that moral conduct needed more than just knowledge of the good; it requires that a person practices the good until it becomes a habit and part of his normal behaviour. Aristotle’s believed that all things of the universe; all the changes that occur in nature as well as the motion of planets were caused by the great power – a “First Cause.” He envisioned this power as an immutable, immaterial, eternal “pure form,” having an intellectual essence. Roman Philosophers The most famous of the Roman Stoics was Emperor Marcus Aurelius (121-180 AD). In his book “Meditations,” he expressed the Stoic philosophy that people should live simple lives, master their emotions, and be self-sufficient. Stoicism, a school of philosophy founded in ancient Greece, was developed from that of the Cynics, whose Greek founder, Antisthenes (444?-371 BC), had been a disciple of Socrates. The Roman orator and Stoic Cicero (1906-43 BC) considered reason as a common possession of both God and man; that obedience to law is one of the requirements of civilized life. He said that individuals are servants of the law in order that they may be free. Epitectus (50-130 AD) also contended that individuals are totally responsible for their actions and must try to accept the consequence of these actions through self-examination. He also stressed that all individuals have duties and obligations to society and are entitled to fundamental rights. THE MEDIEVAL PERIOD The barbarian invasions that had caused the fall of the Roman Empire in the west also destroyed much of the trade the Romans had established among the prosperous European and Middle East cities of the Empire. Most of the Europeans were forced to make their living agriculture, and this ushered the advent of feudalism and the Medieval Period, which was divided into the Early Middle Ages and the Later Middle Ages. Several years later, the Dark Ages (the period known in history where education and cultural activities were almost extinguished) followed. During this period, almost all state and city school disappeared. Few could read and write Latin, the lingua franca of educated citizens. And fewer were educated enough to preserve what little remained of the ancient Greek and Roman Writings. 9 Feudalism and Rise of Nation States When the Western Roman Empire fell, the barbarians divided its provinces into many small kingdoms, which continuously defended themselves from attack by others. In order to protect their domains, the barbarian warlords, initially in France developed “feudalism: a new military, political, and economic system during the early Middle Ages. By the 900’s, most of Western Europe had been divided into fiefdoms or feudal estates. These estates had a system of government whereby the population was divided into lords, vassals, and clergy. The nobles and feudal lords were ruling class. They collected taxes, acted as judges, and maintained an army to protect their estates. The peasants became vassals who worked on the land in manors (agricultural estates) to support themselves, the lords, and the clergy. They have few rights, were almost completely at the mercy of their masters, and had to pay the latter rent and taxes. The clergy consisted mainly of high - ranking clergymen and monks. They ruled large estates and live much like other noblemen. The monks lived in monasteries or abbeys and spent a large number of hours each day studying, praying, and taking part in religious services. From 1337 to 1453, England and France fought the “Hundred Years’ War” which disrupted trade and exhausted the economies of both nations. Peasants revolted to win freedom from their feudal lords. This weakened the control and power to the feudal lords and gave kings opportunity to gain power over the feudal lords, giving birth to nation – states such as of England and France. These nation-estates developed new forms of government, organized national armies, decreed royal laws and created courts to provide justice throughout their realms. The Power of the Church Shortly after Constantine gave religious freedom to Christians in 313 AD, a strongly relationship was formed was formed between the Church and the Roman Empire. By the late 300’s, Roman Emperor Theodosius proclaimed Christianity as the official religion of the empire. When the Roman Empire collapsed in the 400’s, the Roman Christian Church replaced the Roman Empire as a center of spiritual and political power in Europe. It was during the Middle Ages, when the Western Christian Church became the most influential force that brought together the Europeans. The peoples of Europe gradually began to worship the same Christian God. The Christian Church did not only provide guidance for the people, but also gave light to Western Europe during the Dark Ages, as it became the preserver of the main repository of culture and enlightenment during the period. 10 Gradually, the Church converted into Christians the Germanic tribes who had overthrown the Roman Empire. The Christians civilized these barbarians by introducing them the Roman concepts of government and justice. The Church also collected taxes and created law courts to punish offenders. Churches, monasteries, and abbeys were not only places of worship but also served as hospitals and as inns for weary travellers. The Church, however, also became the largest landholder in Western Europe during these periods. Thus, the Church’s authority and jurisdiction included not only the peoples’ religion, but also their social, political, and economic lives. It also provided the peoples’ knowledge of the natural and physical world, their culture, their sciences and their philosophies. EARLY MEDIEVAL PHILOSOPHICAL THOUGHT When the Church became powerful during the early Medieval period, it started a vigorous campaign to destroy much of the classical writings of the Greek and Roman civilizations, considering them to be pagan, immoral and unChristian. The philosophical concepts of Socrates, Plato, and Aristotle, which asserted that the nature of the universe is ordered, moral, and that it can be known to man through reason, was replaced by supernatural standpoint introduced by the Roman Christian Church. The early Church “Supernatural Standpoint” asserted that the good life for a person was to believe in salvation through Jesus and to devote one’s life to faith, devotion, prayers, and obedience to God and the Church, rather than being achieved through reason, mathematics, science, philosophy and the arts, as advanced by the ancient Greek philosophers. Early medieval theology cantered in learning and the arts devoted in glorifying God. Philosophy was closely related and linked with Scriptural views, and was developed more as a part of Christian theology than as independent field of philosophical or scientific thoughts. The philosophical thoughts of Plato and Aristotle, however, managed to survive, through the efforts and synthesis of two Christian Philosophers; Saint Augustine (354-430), greatest of the Latin Fathers and one of the most eminent Western Doctors of the Church (Augustine's doctrine held that human spiritual disobedience had resulted in a state of sin that human nature was powerless to change), and Saint Thomas Aquinas (1225-1274) sometimes called the Angelic Doctor and the Prince of Scholastics, Italian philosopher and theologian, whose works have made him the most important figure in Scholastic philosophy and one of the leading Roman Catholic theologians. More successfully than any other theologian or philosopher, Aquinas organized the knowledge of his time in the service of his faith. In his effort to reconcile faith with intellect, he created a philosophical synthesis of the works and teachings of Aristotle and other classic sages; of Augustine and other church fathers. 11 THE LATE MEDIEVAL PHILOSOPHY During the later Middle Ages (1100-1400), scholasticism became the predominant philosophy. Its development was primarily due to the translation of Aristotle’s work into Latin, the official language of the Christian Church at that time. Scholasticism is a philosophic and theological movement that attempted to use natural human reason, in particular, the philosophy and science of Aristotle, to understand the supernatural content of Christian revelation. The ultimate ideal of the movement was to integrate into an ordered system both the natural wisdom of Greece and Rome and the religious wisdom of Christianity. St. Thomas Aquinas (1225-1274) One of the greatest scholastics of his time was Saint Thomas Aquinas. He made use of the writings of Aristotle, but prudently avoided conflict with Church doctrines by distinguishing between philosophy and theology. According to him, Catholic theological doctrines were not to be subjected to the rational discussion and proofs of philosophy, since they were “revealed truths” based on faith alone and, therefore, not provable or disprovable by reason. He considered other philosophical propositions as just forming a “natural” theology, which he claimed as being different from “revealed” theology but nonetheless were part of Christian philosophy. Saint Aquinas also viewed the universe as a hierarchy of things and beings, each with its own form and purpose from the least significant to the highest. He saw at the apex of this hierarchy, God as the Creator of this chain of existence, as well its first cause and final purpose. For him, God is both the ultimate truth and goodness, and the source of man’s salvation. Aquinas also viewed knowledge as a hierarchy: the “revealed truths” of Christian theology at the highest level; the rational principles of philosophy at the next level, and the scientific knowledge at the bottom. He also described man having a dualistic nature - that is; he is composed of both a natural being and a spiritual being. As a natural being, he was species having his own natural, rational, and political goals, and as a spiritual being; he served a Divine purpose, a Supreme Being (God), who is higher and greater than his ends and purposes. The synthesis of his works and that of Aristotle’s brought the Summa Theologica – a composite study of theology, metaphysics, ethics and politics. Pope Leo XIII declared Aquinas’ concepts as absolute truth and it became the official philosophy of the Roman Catholic Church during those times. 12 Renaissance Philosophy The long period of wars, epidemics (notably the Black Death), and economic depression in Europe came to an end. In the 14th century, these developments led to the beginning of a dynamic era - the Renaissance. Renaissance, (from the French word meaning “rebirth.”) originally referred to the revival of interest in the classical learning of Ancient Greece and Rome, which began in the 1300’s. Later, however, the term came to be applied to the period in which far-reaching developments occurred in the arts, intellectual life, and the ways of viewing the universe. The renaissance movement began in Northern Italy and spread to other countries like England, France, Germany, the Netherlands and Spain. The impetus for this movement came with the fall of Constantinople to the Turks in 1453, which made available to Western Europe a greatly increased amount of the vast learning of the Greek culture that had been preserved in the Byzantine Empire. This Renaissance revival of Greek and Roman studies emphasized the value of the classics for their own sake, rather than for their relevance to Christianity. Humanism Humanism in philosophy is an attitude that emphasizes the dignity and worth of the individual. A basic premise of humanism is that people are rational beings who possess within themselves the capacity for truth and goodness. The term humanism is most often used to describe a literary and cultural movement that spread through Western Europe in the 14th and 15th centuries. In the middle of the 14th century, Italian scholars had lively interest in classical literature. They tried everything they learned from classical antiquity and harmonized them with Christian doctrine. Renaissance humanists believed that human beings, through their power of reason, have the ability to understand nature, and achieve which is good for humanity. Good life meant a meaningful life governed by a life of reason, achieving all the needs of the individual in harmony with the needs of other individuals. The humanistic spirit was also expressed in the artistic endeavours of the period, which emphasized the Greek enthusiasm for life in this world. Humanists considered human existence not only a preparation for life to come but also as a joy in itself. Man, with all his faults, was an intelligent being, who could make his own decisions. Along with this concept of “individual dignity” brought also the admiration for individual achievement. Thus, artists and architects glorified men and nature in their works, instead of church and religious symbols. 13 Petrarch and Erasmus Francesco Petrarch, the Father of Humanism was an Italian poet (born in 1304) who rediscovered a number of Roman authors whose works had been forgotten during the Middle Ages. He was able to build up a collection of 200 classical works, which he bequeathed to the city of Venice. Inspired by Greek humanism, Desiderius Erasmus (1466-1536), Dutch writer, scholar, and humanist, became the chief interpreter of the intellectual currents of the Italian Renaissance in northern Europe. He placed an important emphasis on the autonomy of human reason and the importance of moral precepts. As a Christian, he classified three forms of law: laws of nature thoroughly engraved in the minds of all men; laws of works; and laws of faith. Erasmus was convinced that philosophers, who study laws of nature, could also produce moral precepts related to those in Christianity. He believed that Christian justification came ultimately only from the grace attained by individuals who followed the laws of faith. He asserted that: “faith cures reason, which has been wounded by sin.” Decline of the Power of the Church During the time of Pope Innocent III, the Church took an increasingly active role in political affairs, which irked some European rulers. In later years, there was the conflict between Pope Boniface VII and Philip IV of France when the latter demanded that the clergy pay taxes. The Pope ordered the clergy not to pay taxes without his consent. The French king retaliated by ordering the seizure of the Pope and held him prisoner. Within the Church itself, there developed dissensions such that instance when the French Pope who was installed by the French king, transferred the seat of the papacy from Rome to Avignon, in southern France. The next six popes were also Frenchmen, and Avignon became the seat of the Church for about 70 years. This is known in history as the Babylonian Captivity in reference of the time when the Israelites were prisoners in Babylonia. The period of hostile conflicts from 1379 to 1417 between the Italian popes and the French popes is known as the Great Schism. Such conflicts damaged the reputation of the Church, and brought severe criticisms against Church teachings and practices which led to Protestant Movement of Martin Luther and other reformers in the 1500’s. 14 Conflict between the Church and Science The Church opposed vigorously new scientific claims that undetermined their doctrines. Astronomers by the 16th century began to assail scientific soundness of the geocentric theory (the belief that the earth is the center of the universe). This theory was proposed in the 2 nd century by Ptolemy of Alexandria, Egypt, and became the official view held by the Roman Church. But in 1543, the Polish astronomer Nicholas Copernicus in his book on the Revolutions of the Heavenly Spheres concluded that it is actually the earth that revolves around the sun, not the other way around. The Church refused to accept this new view, (the heliocentric theory was proposed by Aristarchus of Samos in the 200’s B.C.), and responded by excommunicating and condemning to hell those holding such a heretical view, as well as sentencing some to imprisonment, torture, or death by burning at the stake, and also accusing them being atheists. Johann Kepler and Galileo In the early 1600’s Johann Kepler, a German astronomer, successfully tested Copernicus heliocentric theory by using mathematics as his tool. From what was earlier written by Copernicus that the earth and other planets were around the sun in orbits, which are exact circles, Kepler found out that the orbits are not exact circles, but ovals called ellipses. Later Galileo, through his telescope, saw more of the heavens, the valleys and mountains of the moon, the rings of Saturn. His discovery that the moon of Jupiter revolved around the planet helped him disproved the geocentric theory, because it showed that not every heavenly body revolves around the earth. In 1632, Galileo published his findings called Dialogue on the Two Great Systems of the World. The Church rejected Galileo’s findings. He was summoned to appear before an Inquisition at Rome. He was ordered to recant, which he did, but the new scientific ideas continued until accepted by later scientists. The Galileo Controversy Galileo understood that “reason” is a scientific inference based on experiment and demonstration. Experimentation was not a matter simply of observation; it also involved measurement, quantification, and formulization of the properties of the objects being studied. He rejected, for example, Aristotle’s claim that every moving thing had a mover whose force had to be continually applied. Galileo found that it was impossible to have more than one force operating on the same body at the same time. For him, without the principle of a singular mover, it was also conceivable that a transcended God could have “started” the world, and then left it to move on its own. 15 Galileo’s discovery sparked great controversy within the Catholic Church. He also theorized that the universe might be indefinitely large. Realizing his conclusions were in contradiction with Church teaching, he followed Augustine’s rule that an interpretation of scripture should be revised when it confronts properly scientific knowledge. The Church forced Galileo to recant his findings in an Inquisition and formally condemned the latter on these reasons: 1. The Church held a literal interpretation of Holy Scriptures, particularly of the account of creation in genesis where it was stated that the earth was the center of the universe. Also in the Old Testament, Joshua once commanded the sun “to stand still” which implied that the sun normally moved around the earth. 2. The Church was biased against “new sciences” and treated them as sources of magic and astrology. Galileo belonged to these new sciences. 3. These new scientific discoveries and observations radically affected much of the traditional views of the universe that in the process, had undetermined the Church’s influence. Moreover, the new scientific views supported many Protestant views of determinism against the Catholic beliefs on free will. Determinism is a philosophical doctrine holding that every event, mental as well as physical, has a cause, and that, the cause being given, the event follows invariably. This theory denies the element of chance or contingency. It is opposed to indeterminism, which maintains that, in phenomena of the human will, preceding events do not definitely determine subsequent ones. Because determinism is generally assumed to be true of all events except volition, the doctrine is of greatest importance when applied to ethics. The Human Being in Modern Western Philosophy It is generally accepted concept that; the philosophy of a people is largely influenced by their social and cultural environment. This is also true of philosophers, whose concepts have evolved in response to the political, social and economic conditions present in their times. The new data and information gained from scientific investigations during the modern times produced radical changes in beliefs and theories about the world. Philosophers looked more to the sciences for answers to their questions about life, the universe, and the kind of society that would foster man’s well being, rather than to the medieval philosophy of scholasticism, or to the Church traditional doctrines. Thus, Modern Philosophy, which after the Renaissance had France, England and Germany distinctly developed their characteristic philosophy. 16 Philosophical Movements The Age of Enlightenment came about from 1650 to1770 (also known as Age of Reason) the period in history in which there was great enthusiasm for rational thinking throughout Europe and America. The period used the term Age of Enlightenment to describe the trends in thought and letters during the 18th century prior to the French Revolution (1789-1799). The phrase was frequently employed by writers of the period itself, convinced that they were emerging from centuries of darkness and ignorance into a new age enlightened by reason, science, and a respect for humanity. Furthermore, a parallel and new philosophical view premised upon the doctrine of natural law emerged during this period. The discovery of the science of the order, harmony, and lawfulness of nature led to the concept of Natural Law. The viewed humans as being ruled by a “natural Law,” and provides them the power through reason to discover scientific truths about both physical and human nature. Natural Law, (in ethical philosophy, theology, law, and social theory), is a set of principles, based on what are assumed to be the permanent characteristics of human nature that can serve as a standard for evaluating conduct and civil laws. It is considered fundamentally unchanging and universally applicable. Because of the ambiguity of the word nature, the meaning of natural varies. Thus, natural law may be considered an ideal to which humanity aspires or a general fact, the way human beings usually act. Natural law is contrasted with positive law, the enactments of civil society. The doctrine of Natural Law stated that all men are equal, and have the same natural rights of life, liberty and property. In Germany, the philosophy of idealism was developed. Reality, as seen by the idealists, is spiritual and dependent upon the human mind for its validity. Idealism is a theory of reality and of knowledge that attributes to consciousness, or the immaterial mind, a primary role in the constitution of the world. More narrowly, within metaphysics, idealism is the view that all physical objects are mind-dependent and can have no existence apart from a mind that is conscious of them. This view is contrasted with materialism, which maintains that consciousness itself is reducible to purely physical elements and processes— thus, according to the materialistic view, the world is entirely mind-independent, composed only of physical objects and physical interactions. In epistemology, idealism is opposed to realism, the view that mind-independent physical objects exist that can be known through the senses. Metaphysical realism has traditionally led to epistemological skepticism, the doctrine that knowledge of reality is impossible, and has thereby provided an important motivation for 17 theories of idealism, which contend that reality is mind-dependent and that true knowledge of reality is gained by relying upon a spiritual or conscious source. Other philosophies soon emerged such that of the political philosophy of Karl Marx who called for a world revolution to overthrow capitalism and all its institutions, as a cure for the social evils brought about by the Industrial Revolution. Marxist philosophy eventually became dogma, and accepted by modern revolutionary movement in Russia (1917) and China (1922). Developments in the early 19th century, such that of the Russian Bolshevik Revolution, World War I, and Great Economic depressions of the 1930’s led to a pessimistic attitude of peoples everywhere, and this was reflected in philosophical thought called existentialism. In general, Existentialism viewed humanity as suffering from chronic anxiety and foreboding, resulting from what it saw as the meaningless and “emptiness” of human existence. The Frenchman Jean-Paul Sarte (born in 1905) became the leading advocate of existentialism which later fell under a sub-field of a broader movement called phenomenology that is, it seeks to understand phenomena. In America, the new philosophy of transcendentalism, (“that which is beyond human experience,”) emerged in the late 1700’s. the chief proponent of this movement was the American poet Ralph Waldo Emerson (1803-1882). Transcendentalism proposed views opposite to that of empiricism, contending that ‘knowledge is not limited to experience and observation, but is knowable also by reason.” Also in America, pragmatic philosophy came into being. Pragmatism evaluates the truthfulness and value of an idea according to its practical consequence and effect on those who believe the idea, and limits a true idea to being one that works. Prominent pioneers of the pragmatism movement were Charles Sanders Pierce, (1839-1914; William James (1842-1910; and John Dewey (1859-1952). Pragmatism, philosophical movement that has had a major impact on American culture from the late 19th century to the present. Pragmatism calls for ideas and theories to be tested in practice, by assessing whether acting upon the idea or theory produces desirable or undesirable results. According to pragmatists, all claims about truth, knowledge, morality, and politics must be tested in this way. Pragmatism has been critical of traditional Western philosophy, especially the notion that there are absolute truths and absolute values. Although pragmatism was popular for a time in France, England, and Italy, most observers believe that it encapsulates an American faith in know-how and practicality and an equally American distrust of abstract theories and ideologies. 18 Rational and Empirical Methods The search for true knowledge from the sciences was approached into two ways: the rational method and the empirical method. The rational method applied deductive reasoning type of reasoning used in the formulation of mathematical principles, whereby logical conclusions are reached from certain self-evident and intuitively known premises, rather than from those known through experience.) The empirical method is based upon sensory experience, observation, experimentation, and inductive reasoning, from which conclusions can be attained from proven or known facts. Descartes (1596-1650) Rene Descartes, the acknowledged founder of rationalism, hoped that philosophy would end the prejudice and discrimination being perpetrated by the Church against those who held scientific but contrary views against its doctrine. Like Plato, Descartes believed that reason is universal in all men and that is the most important element in human nature. He claimed that only science and mathematics provided sure source of true knowledge, since sensory perceptions are often deceptive; and therefore, unreliable. Thus, he believed that mathematical principles of intuition and deductive reasoning are more superior to that of empiricism, which is based on sense experience. Empiricism Empiricism directly opposed rationalistic concept arguing that what is knowable to human understanding is limited to that which is perceivable by sensory perceptions; that sense experiences and experimentation are the only reliable sources for gaining true knowledge. For anything to be real, valid and true, it must pass the test of being knowable by sense perception. If the knowledge is not based upon such observations by the senses, then it is considered to be only an opinion, or theory, a product of the imagination. Hegel’s Dialectical Idealism Hegel’s dialectical idealism believed that human beings were working out a universal history moving out toward “the consciousness of Freedom on the part of Spirit.” Any given stage could serve as the thesis. The opposing stage or mode of organizing social affairs was the anti-thesis, the eventual compromise of the thesis and the antithesis became the synthesis, which became in turn, the new thesis, and the process began all over again. 19 Karl Marx (1818-1833) Marx, considered as the most influential sociologist of all time, believed that the exploitative conditions in the factories in a capitalist system could not be corrected without a worldwide proletarian revolution. The world revolution would liberate men from alienation brought about human greed and selfishness. Theory of Alienation By “human alienation,” Marx argued that man working under the system of industrial capitalism, no longer considers what he produces as an extension of creative self. The products of his efforts become the property of others and he feels that his work is no longer for his own personal benefit, but is just labor forced upon him by exploitative capitalists. The worker is also alienated from others, because the competitive nature of capitalism pits man against man in the greedy struggle to amass profits and wealth. As a result of alienation, man becomes machine-like, and consequently, is reduced to functioning at the level of animals, producing only to satisfy his basic, personal, and psychological needs. Dialectical Materialism Karl Marx adopted Hegel’s dialectical method. But unlike Hegel’s dialectics which was based on the realm of ideas, Marx found his dialectical evolution in the context of material conditions, thus, he coined the word dialectical materialism. According to him, human history is moving, according to dialectics, through five stages of economic development namely: primitive, communalism, slavery, feudalism, capitalism, and socialism. For Marx, the passion of greed for money is the driving force of the capitalistic world. Money worship has become ingrained in man’s essence; all powerful master to which he is a slave. Greed for money has pervaded every aspect of life; the family, morality, religion, the economy, and politics, further alienating human beings from their selves. Theory of World Revolution After the victory of a world revolution, men can overcome alienation by seizing the control of private property from the capitalists and making it the common property of all. For Marx, labor itself will be abolished, and all remnants of capitalistic power must be destroyed. However, a centralized system of production must be installed under the hands of the proletariat. Man will no longer be alienated by exploitative working conditions; he will dominate and control them. Rather than wages strictly for work or services rendered, the ultimate principle of Communism will be, “From each, according to his ability; to each, according to his needs.” 20 Historical Materialism For Marx, throughout all of history, the principal ideas and concepts of society, culture, and politics have been rooted in and determined by economic structures. The ideas and values of the ruling class have always been the ideas which had dominated the consciousness of society. This situation had always served well the interests of the dominant ruling-class, which had always the means of production at its disposal. Thus, the beliefs of a society, and its ideology, are determined by the dominant class, and reflect and promote its economic interests. Thus, according to Marx, the history of mankind is but a record of class struggles in which the ownership of the means of production plated a vital role. In short, Marx, “Historical Materialism” defines history as the story of class antagonisms between masters and slaves, feudal lords and serfs, propertied and property-less class, landlords and landless, and the exploiters and exploited class. CONCEPTS RELATED TO PERSONAL AND INSTITUTIONAL PHILOSOPHIES What are concepts? Conceptualism in philosophy is a theory that is intermediate between nominalism and so-called medieval, or logical, realism. It maintains that although universals (abstractions or abstract ideas) have no real existence in the external world, they do exist as ideas or concepts in the mind and are thus something more than mere words. The theory contradicts nominalism, which holds that abstractions (universals) are mere figments of language, without substantive reality, and that only individual objects have real existence. Conceptualism was espoused by the French Scholastic. Human Nature, essential qualities shared by all humans. Philosophy has often been concerned with identifying what constitutes and drives human nature and with determining whether human nature is essentially good or evil. Being - is a state of existence or reality. Questions about what it means to exist as a person, as a conscious entity, and questions about what is ultimately real, have been the basis of much philosophical and religious thought. The state of being of a rural community often being backward, on the other hand, is the focus of any development intervention. Creativity, capacity to have new thoughts and to create expressions unlike any other. Creativity is a basic element in many human endeavors, such as art, music, literature, and performance. In like manner, rural development programs should be creatively planned in to make them acceptable to the intended beneficiaries. 21 Goal - purpose or objective toward which an endeavour is directed. Will is the capacity to choose among alternative courses of action and to act on the choice made, particularly when the action is directed toward a specific goal (this can be individual or group goals) or is governed by definite ideals and principles of conduct. Willed behavior contrasts with behavior stemming from instinct, impulse, reflex, or habit, none of which involves conscious choice among alternatives. Willed behavior contrasts also with the vacillations manifested by alternating choices among conflicting alternatives. Causality, in philosophy, is the relationship of a cause to its effect. The Greek philosopher Aristotle enumerated four different kinds of causes: the material, the formal, the efficient, and the final. The material cause is what anything is made of - for example, brass or marble is the material cause of a given statue. The formal cause is the form, type, or pattern according to which anything is made; thus, the style of architecture would be the formal cause of a house. The efficient cause is the immediate power acting to produce the work, such as the manual energy of the laborers. The final cause is the end or motive for the sake of which the work is produced - that is, the pleasure of the owner. The principles that Aristotle outlined formed the basis of the modern scientific concept that specific stimuli will produce standard results under controlled conditions. In early modern philosophy, Aristotle's laws of causality were again challenged. The French philosopher and mathematician René Descartes and his school believed that a cause must contain the qualities of the effect or the power to produce the effect. The British philosopher David Hume carried to a logical conclusion the contention of Sextus Empiricus that causality is not a real relation, but a fiction of the mind. To account for the origin of this fiction Hume used the doctrine of association. Hume's explanation of cause led the German philosopher Immanuel Kant to posit cause as a fundamental category of understanding. Kant held that the only knowable objective world is the product of a synthetic activity of the mind. He accepted Hume's skeptical result as far as it concerned the world of things. Dissatisfied, however, with the concept that experience is only a succession of perceptions without any discoverable relationship or coherence, Kant decided that causality is one of the principles of coherence obtaining in the world of phenomena, and that it is universally present there because thought, as part of its contribution to the nature of that world, always puts it there. The British philosopher John Stuart Mill took up the problem at this point. He denied the fundamental postulate of Kant's transcendentalism, namely, that thought is responsible for the order of this world. Mill sought to justify belief in universal causation on empiricist principles; for him, a proposition is meaningful only if it describes what can be experienced. 22 Free Will, power or ability of the human mind to choose a course of action or make a decision without being subject to restraints imposed by antecedent causes, by necessity, or by divine predetermination. A completely freewill act is itself a cause and not an effect; it is beyond causal sequence or the law of causality. The question of human beings’ ability to determine their actions is important in philosophy, particularly in metaphysics and ethics, and in theology. Generally, the extreme doctrine in which freedom of the will is affirmed is termed libertarianism; its opposite, determinism, is the doctrine that human action is not willed freely, but is rather the result of such influences as passions, desires, physical conditions, and external circumstances beyond the control of the individual. Traditional Values, principles or standards followed and revered by a people continuously from generation to generation. These traditional values can either support or impede development efforts in rural communities. Happiness is a state of joy, pleasure, goodness, or satisfaction of an individual or group of individuals. It is the ultimate goal of human development. Harmony is the right and desirable relationship of parts to a whole, whether in nature, society, or an individual. A development program should be a part of a larger community, country, and regional goal. Nonviolence, doctrine or practice of rejecting violence in favor of peaceful tactics as a means of gaining political or social objectives. Nonviolence, doctrine or practice of rejecting violence in favor of peaceful tactics as a means of gaining political or social objectives. Positivism, system of philosophy based on experience and empirical knowledge of natural phenomena, in which metaphysics and theology are regarded as inadequate and imperfect systems of knowledge. Pluralism, theory that reality is composed of many parts and that no single explanation or view of reality can account for all aspects of life. Pluralism also refers to the acceptance of many groups in society or many schools of thought in an intellectual or cultural discipline. Altruism, devotion to the welfare of others. It is the English form of the French word altruisme created by the 19th-century French philosopher and sociologist Auguste Comte from the Italian word altrui, meaning “of or to others.” The word has gradually come into more general use. In philosophy altruism describes a theory of conduct that aspires to the good of others as the ultimate end for any moral action. In theories of ethics, altruism is the antithesis of Egoism, the doctrine or attitude that one's own interests are of greater importance than any other consideration or thing. 23 Individualism, in political and economic philosophy, the doctrine, promulgated by such theorists as English philosopher Thomas Hobbes and Scottish economist Adam Smith, that society is an artificial device, existing only for the sake of its members as individuals, and properly judged only according to criteria established by them as individuals. Individualists do not necessarily subscribe to the doctrine of egoism, which regards self-interest as the only logical human motivation. They may instead be guided in political and economic thinking by motives of altruism, holding that the end of social, political, and economic organization is the greatest good for the greatest number. What characterizes such individualist thinkers, however, is their conception of the “greatest number” as composed of independent units and an opposition to the interference of the state with the happiness or freedom of these units. Individualist tendencies or theories play a part in all the sciences that deal with a person as a social being. Although individualism would theoretically consider the state as placing an artificial restraint on a person's individual tendencies, practical distinctions between individualism and its antitheses, such as socialism, are often difficult to make. Like individualism, socialist or collectivist theories may place high value on the well-being and free initiative of the individual. Individualism differs from such theories in asserting that the welfare of the individual is of the highest value and that each individual exists as a unique end, with society serving only as a means to accomplish the ends of the individual. Instrumentalism in American philosophy is a variety of pragmatism developed at the University of Chicago by John Dewey and his colleagues. Thought is considered by instrumentalists a method of meeting difficulties, particularly such difficulties as arise when immediate, unreflective experience is interrupted by the failure of habitual or instinctive modes of reaction to cope with a new situation. According to the doctrine, thinking consists of the formulation of plans or patterns of both overt action and unexpressed responses or ideas; in each case, the goals of thought are a wider experience and a successful resolution of problems. In this view, ideas and knowledge are exclusively functional processes; that is, they are of significance only as they are instrumental in the development of experience. The realistic and experimental emphasis of instrumentalism has had a farreaching effect on American thought; Dewey and his followers applied it with conspicuous success in such fields as education and psychology. Truth, a concept in philosophy that treats both the meaning of the word true and the criteria by which we judge the truth or falsity in spoken and written statements. Philosophers have attempted to answer the question “What is truth?” for thousands of years. The four main theories they have proposed to answer this question are the correspondence, pragmatic, coherence, and deflationary theories of truth. 24 Fatalism, doctrine that all events occur according to a fixed and inevitable destiny that individual will neither controls nor affects. Fatalism frequently is confused with determinism, the doctrine that events are determined by the events that precede them. According to fatalism, preceding events have no causal connection with the events that follow. A fated event takes place not according to a natural law but in accordance with some mysterious decree issued by some mysterious power, perhaps ages before. Determinism, in its tenet that every event has its determining conditions in its immediate antecedents, which may include the human will, is consistent with a belief in the efficacy of the human will, but fatalism is not. Both fatalism and determinism, thus distinguished from each other, should likewise be distinguished from predestination. Predestination is determination plus the belief in a supernatural power that has established a determining natural sequence of causes. Fatalism is a belief in a supernatural power that predetermines without recourse to natural order. Fatalism appeared among the ancient Hebrews, Greeks, and Romans and today is particularly prevalent among Muslims. In the modern Occident, though, it has retained a degree of acceptance only where science has not had a controlling influence in developing the doctrine of causality. Utilitarianism (Latin utilis, “useful”), is the doctrine that what is useful is good, and consequently, that the ethical value of conduct is determined by the utility of its results. The term utilitarianism is more specifically applied to the proposition that the supreme objective of moral action is the achievement of the greatest happiness for the greatest number. This objective is also considered the aim of all legislation and is the ultimate criterion of all social institutions. The utilitarian theory of ethics is generally opposed to ethical doctrines in which some inner sense or faculty, often called the conscience, is made the absolute arbiter of right and wrong. Utilitarianism is likewise at variance with the view that moral distinctions depend on the will of God and that the pleasure given by an act to the individual alone who performs it is the decisive test of good and evil. Pessimism, doctrine that reality, life, and the world are evil rather than good. Pessimism generally takes one of two forms: that of an entrenched negative state of mind, or a permanent expectation of the worst under all circumstances, and that of a philosophical system. The former instance may arise, depending on the temperament of the individual, from the reaction of a person to the difference between the world as it is and the world as it could be. The existence of evil and the link between suffering and sin have been dwelt upon since ancient times; one example is the ancient Hebrew Book of Job. 25 Self Assessment 1 1. In a matrix format, trace the historical development of philosophies that acknowledge the importance of human beings and the society to which they belong. 2. What prohibited early scientists from advancing scientific investigations in the past? What is the role philosophy in the development of science? Activity 1 1. Write down your agency’s/department’s philosophy, mission, vision and goal. Analyze such institutional philosophy and determine if it is in conformity with the objectives which your agency/department undertakes. 2. If you were tasked to establish a new agency/department that would highlight your expertise, how will you write an institutional philosophy that will embody your ideals and vision as prime mover of rural development interventions? Explain its meaning. References Adler, M. 1967. Great Gooks. Cruz, C. 1995. Philosophy of Man. 3rd Ed. MG Reprographics, Manila. Microsoft ® Encarta ® 2006. © 1993-2005 Microsoft Corporation. All rights reserved. Retried from http/www.encarta.library.com. Farber, M. 1968. Basic Issues in Philosophy. Harper, London. Maguigad, R. 2006. Philosophy of the Human Being. Libro Filipino Enterprises, Manila. Marx, K. 1961. Selected Writings in Sociology and Philosophy. Wats and Company, London. Reyes, R. 1986. The Elements of Society: The Social Philosophy of Edmund Husserl,” Paper presented at the 1986 Annual Convention of the Philosophical Association of the Philippines. ________ A History of Philosophy. Vol. VII. Part II. New York. Image Books.