* Your assessment is very important for improving the work of artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download Document

Sanskrit grammar wikipedia , lookup

Comparison (grammar) wikipedia , lookup

Preposition and postposition wikipedia , lookup

Old Norse morphology wikipedia , lookup

Ojibwe grammar wikipedia , lookup

Old Irish grammar wikipedia , lookup

Transformational grammar wikipedia , lookup

Arabic grammar wikipedia , lookup

Kannada grammar wikipedia , lookup

Untranslatability wikipedia , lookup

Compound (linguistics) wikipedia , lookup

Modern Greek grammar wikipedia , lookup

Zulu grammar wikipedia , lookup

Agglutination wikipedia , lookup

Old English grammar wikipedia , lookup

Macedonian grammar wikipedia , lookup

Swedish grammar wikipedia , lookup

Chinese grammar wikipedia , lookup

Modern Hebrew grammar wikipedia , lookup

Portuguese grammar wikipedia , lookup

Lithuanian grammar wikipedia , lookup

Lexical semantics wikipedia , lookup

Vietnamese grammar wikipedia , lookup

Japanese grammar wikipedia , lookup

Icelandic grammar wikipedia , lookup

Serbo-Croatian grammar wikipedia , lookup

Esperanto grammar wikipedia , lookup

Romanian grammar wikipedia , lookup

Determiner phrase wikipedia , lookup

Yiddish grammar wikipedia , lookup

Morphology (linguistics) wikipedia , lookup

Ancient Greek grammar wikipedia , lookup

Turkish grammar wikipedia , lookup

French grammar wikipedia , lookup

Scottish Gaelic grammar wikipedia , lookup

Latin syntax wikipedia , lookup

Spanish grammar wikipedia , lookup

Polish grammar wikipedia , lookup

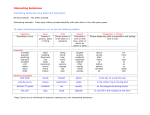

Malay grammar wikipedia , lookup

4.1 Syntax and grammar As another subfield of linguistics, syntax is the study of sentence structure. It is concerned with the rules of how words are put together in certain patterns to form different sentences. As inflections are used by speakers to indicate the grammatical relations between the words in a sentence, traditionally "grammar" refers to syntax and the part of morphology that deals with inflections. This is what we mean by saying "the grammar of the sentence" or "a grammatical study of sentences". We are not using the term "grammar" in the sense Chomsky uses it to call his linguistic theories. 4.2 Word order As we have mentioned before, syntax deals with the patterned relations between words in the sentences, and with the systematic means of stating and analyzing such patterns. By saying that the relation between words in a sentence is patterned, we mean that there are rules which govern the ways words are put together. Let us consider the following sentences: 1. The children sleep peacefully. 2. *Sleep children peacefully the. 3. The ideas sleep furiously. 4. *Ideas the furiously sleep. Sentences 1 and 3 are normal English sentences in that they are grammatically well-formed sequences of words. Being grammatically well-formed mainly means that the words in the sentences are ordered according to syntactic rules of English by following certain patterns, such as "determiner + noun + verb + adverb". Sentence 3 is not meaningful in non-poetic context, but this lack of meaningfulness does not negate its grammaticality. Put in a poetic context, it is meaningful if we stretch our imagination a bit. But sentences 2 and 4 are ungrammatical (hence the asterisk.), because they violate the syntactic rules which control the word order, position of words of various classes relative to one another in sentences. Word order is particularly important to English as it is not so inflectional as some other Indo-European languages. The grammatical functions performed by inflections in highly inflectional languages are therefore performed by word order in English. For example in English the identities of subject or object are solely determined by word order, not by the inflections indicating a subjective or objective case. Word order is often referred to by the term syntagmatic relation. 4.3 Word classes As we have mentioned before, syntax is the patterning of words in the sentences. Speakers of one language do not have total freedom in combining words to make sentences. They have to follow certain syntactic rules concerning the patterning of words, for example, the word order "determiner + noun + verb +adverb" mentioned in the previous section. Words are put together in this order according to the classes they belong to. Word classes are sets of words, which have the same grammatical limitations and the same potential for occurrence. That is to say, they are likely to fit into the same slot in a sentence and mutually substitutable in particular grammatical context. For example, all the words in "The children sleep peacefully" can be substituted by words of the same classes: 1. A cave collapsed suddenly. 2. That man wrote slowly. 3. Those dogs barked angrily. The resulting sentences of the substitution are all grammatical, because the, a, that, those belong to the same word class "determiner"; children, cave, man, dog are all the members of the class "noun"; sleep, collapse, write, bark are "verbs" and peacefully, suddenly, slowly, angrily are "adverbs". We are quite familiar with such terms as "nouns", "verbs", and "adverbs" since they are traditionally referred to as parts of speech. However, in many linguistic works the term "word class" is used instead of "part of speech". Linguists insist that words should be solely classified in accordance with their syntactic properties, their distribution in sentences, as in the above discussion. They regard the traditional definition for parts of speech, such as "A noun is the name of any person, place, or thing", "A verb is a word which denotes an action", "An adjective modifies a noun", as a mixture of inflectional, syntactic and semantic description and as logically defective or circular. The syntactic relation of substitution between words of the same class is also referred to as the paradigmatic relation. The term "paradigmatic" is often used along side with the term "syntagmatic" to specify the two different linguistic relations, "vertical" and "horizontal", at many levels of linguistic system other than words. Syntagmatic and paradigmatic relations are not confined to the relations between single words. For example, in "Whoever takes this pill will sleep peacefully", the primary syntagmatic relation is the one that exists between * "whoever takes this pill", "will sleep" and "peacefully". If the sentence is substituted by "The children sleep peacefully", then there is a paradigmatic relation between "whoever takes the pill" and "children", and between "will sleep" and "sleep". Similar relations also exist on phonological, morphological, phrasal, and even textual levels. In the two phoneme strings /pit/ and /bit/, there is a syntagmatic relation between /p/or /b/, /i/ and /t/, and a paradigmatic relation between /p/ and /b/. In the two words meaningful and meaningless, morphemes mean, -ing and -ful can be viewed as having a syntagmatic relation between them, and the relation between -ful and -less can be viewed as a paradigmatic one. Word classes can be "closed" or "open". If a word class is not expanded by the creation of additional members, it is closed. For example, in English we rarely, if ever, invent or adopt a new or additional pronoun. Semantically closed class words form a system and they are mutually exclusive and usually defined in relation to the rest of the class. On the other hand, an open class is indefinitely extendible. New words are constantly added to open classes. Words belonging to the same open class are not mutually defining. They only have the same grammatical properties and fit into the same slot in a sentence as the other words in the class. In English we have the following closed word classes: Preposition Pronoun Determiner Conjunction in, on, at, in front of, beneath, etc. you, it, his, herself, mine, etc. a, the, this, those, both, etc. but, or, and, etc. Modal verb can, may, must, ought, etc. Primary verb have, be, do. And the following open word classes: Noun Adjective man, dog, China, etc. good, wonderful, green, old, etc. Adverb fast, swiftly, slowly, wonderfully, etc. Full verb run, walk, arrive, beat, etc. 4.4 Word groups We have learned that words are placed one after another in a sentence according to certain word order, but sentences are more than a mere linear sequence of single words. There are word groups in a sentence. For example, in the sentence "The two ugly sisters had gone home without her", it is obvious that certain words, such as had and gone, or the, two, ugly and sisters, "belong together" in a way in which others do not. And had gone appears to have a closer relation with home and without her than with the two ugly sisters. Usually word groups correspond to syntactic categories such as subject, predicate, object, complement, etc. on one hand and clauses or phrases on the other. In the above example, the word group the" two ugly sisters corresponds to the category of "subject" or "noun phrase" with the rest of the sentence can be grouped together as it corresponds to the category of "predicate" or "verb phrase". There is a hierarchical relation between all the possible word groups in a sentence. The idea is that in any given sentences some words are more closely related than others, and a sentence is made up of two-part constructions on a series of levels or layers. The big word groups contain some smaller ones and the smaller ones may in turn contain some still smaller ones. There are groups, subgroups and sub-subgroups. How far the grouping will go is determined by the required depth of syntactic description, but usually we stop at single words. The word groups in a sentence are called its constituents and, when they are considered as part of bigger word groups, they are called its immediate constituents. Immediate Constituents Analysis is the technique of breaking down sentences into word groups by making successive binary cuttings until the level of single words is reached. The single words resulted from an 1C Analysis are called the ultimate constituents. There are many ways to demonstrate the stages of IC Analysis and the resulting constituent structure. For example, to analyze the sentences "In the bank I gave them my application" and "The new product has passed tests with flying colours", we can use vertical bars: 1. In the bank I I gave them my application. 2. In II the bank I I IIgave them my application. 3. In II the III bank II II gave III them my application. 4. In II the III bank I I II gave III them IIIImy application. 5. In II the III bank I I II gave III them IIIImy IIIII application. Or square brackets: 1. [The new product has passed tests with flying colours.] 2. [[The new product] [has passed tests with flying colours.]] 3. [[[The] [new product]] [[has passed tests] [with flying colours.]]] 4. [[[The] [[new] [product]]] [[[has passed] [tests]] [[with] [flying colours.]]] 5. [[[The] [[new] [product]]] [[[[has] [passed]] [tests]] [[with] [[flying] [colours.]]]]] Or tree diagrams: In the bank I gave them my application Figure 4-1 tree diagram IC analysis of this kind does not give labels to the constituents. If syntactic labels are used to indicate the constituents, we will have a "labeled tree diagram": S PP S NP VP Pron NP V NP Pron NP P Det N Det N In the bank I gave them my application. Figure 4-2 labeled tree diagram Or a "labeled square bracketing": [S[NP[Det The] [NP[A new] [Nproduct]]] [vp[vp[tense has] [vpassed]] [Ntests]] [pp[pwith] [NP[A flying] [Ncolours.]]]]] Word groups have two types of constructions: endocentric and exocentric constructions. If the group in question is syntactically equivalent to one of the words it contains, or, to put it another way, if one of the words in the group can stand in place of the whole group, the group is said to have an endocentric construction. If not, the group is said to have an exocentric construction. In an endocentric construction, the word that can stand for the whole group is the head, and the other words are its optional modifiers. Most constructions are exocentric. for example, the English prepositional phrases with care, from the village, on the table and subordinate clauses if you are here, because it won't do, which you like are exocentric constructions made up of a preposition and a noun phrase, or of a conjunction and a clause. Neither of the two parts in either case is syntactically equivalent to the adverbial or modifier they make together. The typical English endocentric constructions are noun phrases and adjective phrases. Take the sentence "The beautiful red dress is very good indeed" for example. The head dress of the noun phrase the beautiful red dress and the head good of the adjective phrase very good indeed can replace the whole phrase respectively in the sentence as there are syntactically the same. 4.5 Grammatical categories The term "grammatical category" is used by some linguists to refer to word class. In TG grammatical categories are syntactic units indicated by "category symbols" such as S, NP, VP, Det, A, etc. But, in more general use, the term refers to certain defining properties of word classes with corresponding inflectional affixes as their formal indications. The inflectional affixes characterize individual word forms, not lexemes. For example, the lexeme "book" has two word forms: the singular book and the plural books. Together they constitute the category of number in English indicated by suffix -s. Similarly, the non-past work and the past worked of the lexeme "work" form the category of tense in English indicated by the suffix -ed. Apart from number and tense, there are case and gender for nouns and adjectives, and aspect, voice and mood for verbs. These grammatical categories are an essential part of the inflectional languages. Many of them are still used in the description of the English language even though the formal indication of them has almost entirely lost long before. Gender is an arbitrarily fixed characteristic of individual nouns, pronouns, or other words in the noun phrases such as determiners and adjectives. Many inflectional languages have three meaning-related gender distinctions: masculine feminine and neuter. We can say that English has no gender because nouns, determiners, adjectives in English have no inflectionally marked gender distinctions. The suffix -ess in princess, duchess, actress, etc. are derivational not inflectional. The choice of English pronouns is based semantically on the non-arbitrary, natural distinction of sex. This "notional gender" in English should be talked about in terms of "male" and "female" instead of "masculine" and "feminine". Compare the following French sentences with their English counterparts: Le cadeau (masculine) est beau. La maison (feminine) est belle. The gift is fine. The house is fine. Gift and house have no sex distinction but they are arbitrarily distinguished in French as masculine and feminine, and there is a gender agreement among the determiner, noun and adjective in the sentence. The category of case applies not only to nouns but also to a whole noun phrase. Cases indicate the syntactic and/or the semantic role of a noun phrase in a sentence. It is very prominent in the grammar of inflectional languages. For example, Latin has six cases: nominative (for subject), vocative (for a noun used in name calling), accusative (for direct object), genitive (for a noun used to modify a higher noun phrase or to indicate a possessive relation), dative (for indirect object) and ablative (for a noun when a departing motion is indicated). Many English pronouns have different forms corresponding to the distinction of subjective (nominative), objective (accusative and dative) and genitive cases, as in I, me, my; we, us, our; he, him, his, etc. Apart from the pronoun system, English has only one case distinction in nouns — the genitive case indicated by the suffix /-iz/, /-z/ and /-s/ in phonetic forms and "apostrophe + s" (boy's), or an apostrophe only (boys') in writing. Ablative n.〈语法〉夺格, 离格(与 by, with, from 等连用) Of, relating to, or being a grammatical case indicating separation, direction away from, sometimes manner or agency, and the object of certain verbs. It is found in Latin and other Indo-European languages. Number is a grammatical category with a relatively clear semantic basis. It is a category primarily for nouns. Not all the English nouns have a singular-plural distinction. Those nouns that have this distinction are called "count nouns". Their regular plural forms are clearly marked by plural suffixes. The other major inflectional categories, such as person, tense, aspect, mood and voice, belong mainly to the verb. The category "person" is overtly marked in English pronoun system. It also belongs to the verbs because the number of the subject is indicated in the verb form when the subject is in the third person and the verb is in the present tense, as in It hurts as against They hurt. Tense shows the relationship between the form of the verb and the speaker's concept of time. In English the formal indication is between past and non-past, with the past formally marked in regular verbs by suffix -ed. Aspect deals with how the event described by a verb is viewed. English has two aspect constructions, the perfective and the progressive, realized by "have + -ed participle" and "be + -ing participle" respectively. Mood involves a choice between indicative, imperative and subjunctive forms of the verb on the semantic basis of the factuality. The English imperative has only a "tenseless" be as the formal marker. Subjunctive mood is used to indicate some of the nonfactual and hypothetical situations. English has two formal markers of the subjunctive mood, the base form and were. When the base form is used, there is a lack of the regular agreement between subject and the finite verb, and the present and the past are not distinguishable. When were is used, there is no indication that the verb is in the past tense or the subject is plural. Compare: Indicative mood He is / was careful. Imperative mood Be careful. Subjunctive mood I demanded that he be careful. If I were you, I would be more careful. Voice is somewhat different from the other grammatical categories. Although it is morphologically a property of the verb, it is closely related to the syntactic structure of the sentence. It makes it possible to view the action of a sentence in either of the two ways without changes in the facts reported. The passive voice of English is realized by "be + -ed participle". The doer in the active sentence is omitted in the passive or is indicated by a "by-phrase" in passive sentence. Compare: Active voice Passive voice Jim caught the ball. The ball was caught. Passive voice with "by-phrase" The ball was caught by Jim. Words occur in a phrase or a sentence in various category-indicating forms. The selection of these forms has two types, government and concord. Government refers to the situation where one word in a phrase or sentence requires that another word in the same phrase or sentence take a particular category form. For example, English prepositions and verbs govern the forms of pronouns that follow them in the same syntactic construction so that the "objective" forms of these pronouns must be used, as in with me, to him, to invite them, to save us, etc. The reflexive pronouns in English are also "governed" by the subject noun in the same clause structure. For example: 1. The boy hurt himself. 2. The woman hurt herself. ; 3. The men hurt themselves. Concord refers to the agreement in a phrase or sentence in terms of marked grammatical categories. English does not have gender concord in a noun phrase as French does. There is only a number concord as shown in the following sentences: 1. This boy goes to school every day. 2. These boys are Chinese. 3. I am a teacher and you are a student. There is a concord of number between this, boy, goes and these, boys, are. And there is also a concord of number and person between I, am and you, are. Sentence structure The grammatical structure of a sentence is traditionally analyzed in terms of the functional categories of its constituents. A sentence is seen as composed of a subject (S) and a predicate(P). The predicate may contain, apart from the verb (V), objects (O), complements (C) and adverbials (A), which are further categorized into direct object (Od), indirect object (Oi), subject complement (Cs), object complement (Co), subject-related adverbial (As) and object-related adverbial (Ao). If we disregard the optional adverbials, we will have seven major sentence types: 1. SV Jane's cat snores. 2. SVO Jane keeps a cat. 3. SVCs Jane is very fit. 4. SVAs . Jane's room is on the second floor. 5. SVOiOd Jane is keeping Archie a piece of pie. 6. SVOCo 7. SVOAo Jane is keeping Archie happy. Jane keeps her cat in the garden. The grammatical structure often corresponds to the semantic structure of sentences, which is analyzed in terms of the semantic roles played by the constituents. These semantic roles normally correspond to certain syntactic categories when the sentence in question is active and with an animate doer. For example, subject usually has a role of an agent and complements are attributes. Indirect object has a role of a beneficiary and direct object is a patient. Adverbials may be instrumental, locative or temporary. The grammatical structure also corresponds to the thematic structure, which is described in terms of the information value of the constituents. The initial constituent of a sentence is called theme and the rest of the sentence rheme. Theme is normally the starting point or the topic and contains given information. As subject in English usually is the first constituent in a sentence, it is often the unmarked theme. The whole predicate is the rheme. However, we will have a different picture when there is passivisation or fronting. The semantic roles of the constituents remain the same but the object can be made subject or fronted to the initial position to become the theme, as shown in the following table: Active sentence Mother Passive sentence my brother this toy. Functional elements subject indirect object direct object Semantic roles beneficiary agent Thematic structure theme My brother patient rheme has been given Functional elements subject this toy direct object by Mother. prepositional object Semantic roles beneficiary Thematic structure theme This toy Fronted direct object has given Functional elements direct object patient agent rheme my brother subject has been given by Mother. prepositional object Semantic roles patient Thematic structure theme beneficiary rheme agent Figure 4-3 thematic structure