* Your assessment is very important for improving the work of artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download monarch butterfly

Ornamental bulbous plant wikipedia , lookup

Plant reproduction wikipedia , lookup

Plant evolutionary developmental biology wikipedia , lookup

Glossary of plant morphology wikipedia , lookup

Pinus strobus wikipedia , lookup

Tree shaping wikipedia , lookup

Ailanthus altissima wikipedia , lookup

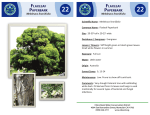

AMERICAN BASSWOOD Many of our native tree genera have species that are native to other continents. Some of these genera may only have 1 species that is native to North America. One of those native species is the American Basswood (Tilia americana L.). American Basswood is a member of the Family Tilaceae, the Subfamily Holopetalae, and the Tribe Tileae. Another scientific name for this tree was Tilia glabra Ventenat. The common name, Basswood, is from “bast”, which is “cordage” or “textile fiber”. Other common names for this species are American Linden, Basswood, Basswood Beetree, Bast Tree, Bee Tree, Black Limetree, Bois Blanc, Lime, Lime Tree, Linden, Linn, Spoonwood, Whistlewood, Whitewood, Wickup, and Yellow Basswood. DESCRIPTION OF THE AMERICAN BASSWOOD Height: Its height is 50-150 feet. Diameter: Its trunk diameter is 16-48 inches. Crowns: Its open area crowns are dense, broad, rounded, and regular. Its forest crowns are narrow and columnar. Its branches are drooping and sagging. Trunks: Its trunks are straight and well formed. There may be more than 1 trunk per tree. These trunks can hollow out in their old age and form cavities for nesting Woodpeckers (Family Picidae) and Wood Ducks (Aix sponsa L.). Twigs: Its twigs are slender or stout, dark gray to green to yellow-brown, smooth, hairless, and zigzag. During their 1st year, they have lenticels. Its leaf scars are semi-oval, raised, and have 5-10 vein scars. Its pith is pale, angled, and continuous. White-tailed Deer (Odocoileus virginianus Zimmermann) eat these twigs. Buds: Its lateral buds are about ¼ inch long, green to bright red, obliquely sessile, acutely tipped, rounded, hairless, smooth, shiny, and have 2-4 visible scales. There are no true terminal buds. Leaves: Its leaves are deciduous, simple, and alternate. They are arranged in 2 rows. Each leaf is about 3-10 inches long, about 2/3 as wide, thin, and broadly ovate to heartshaped (cordated). It has an asymmetrical base and an abruptly pointed tip. Its margins are finely or coarsely serrated and are gland-tipped. These leaves are dull or shiny green on top, paler on the bottom with star-shaped rusty hairs in the vein axils, and have palmated veins. Its petioles are 1-2½ inches long, slender, and have paired stipules that fall off early. These leaves are the largest of all of the Tilia species. They turn light yellow or brown in the fall. When they fall, these nutrient-rich leaves add calcium, magnesium, nitrogen phosphorus, and potassium to the soil. Flowers: Its flowers are arranged in loose, hanging, branched cymed clusters of 3-20. These slender, winged, smooth, gray stalks are attached to the lower midvein of a 4-5 inch long, 1-1½ inch wide, leaf-like, winged, papery, green bract that hangs from the axils of the new leaves. Each flower is creamy yellow or white. It is ½-5/8 inches long and wide. It has 5 petals; 5 sepals; numerous stamens arranged in 5 clusters; and a pistil with a 5-celled ovary, a single style, and a 5-lobed stigma. These flowers contain farnesol, a volatile oil that gives them their fragrance. These flowers produce an abundance of nectar about every other year. Bees (Superfamily Apoidea) and Flies (Order Diptera) pollinate by day and Moths (Order Lepidoptera) pollinate by night. These flowers are in bloom for 2-3 weeks. Flowering season is June to August. Fruits: Its fruits are also arranged in long, wiry, stalked clusters that are attached to the bracts. These bracts later fall off as spinning parachutes. Each fruit is a gray-brown (with fine red-brown wooly hairs), ¼-3/8-inches wide, globose or spherical, unribbed, dry, drupe or nutlet capsule. These fruits have hard, thick shells. Each fruit has 1-2 seeds. These trees can produce seeds after 15 years. Nearly every year, these trees produce many seeds. Blue Jays (Cyanocitta cristata L.), Thrushes (Family Turdidae), Squirrels (Family Sciuridae), Eastern Chipmunks (Tamias striatus L.), and Mice (Genus Mus) eat these seeds. Fruiting season is August to October. Some of these fruits may persist through the winter. They don’t germinate quickly and have about 25% viability. They can remain dormant for up to 4 years. Bark: Its young bark is thin, gray to dark green, and smooth. Its older bark is thicker; dark gray brown; and deeply, longitudinally furrowed with shallow grooves and with black, narrow, scaly, flat-topped ridges. These ridges may be parallel or interlacing. Wood: Its wood is light, soft, brittle, smooth- or close-grained, diffuse-porous, uniform, and odorless. It shrinks when drying and does not easily split. Its heartwood is light redbrown and its thick sapwood is white to light tan. Roots: Its roots are both deep and wide spreading. They may vigorously send up root sprouts around the trunk or around the stump. These trees are windfirm. Habitats: Its habitats consist of cool, moist, rich forests. These forests may be in lowlands and often near water. They are usually found with other deciduous tree species. This tree is shade-tolerant when young but becomes less tolerant as it ages. This is also a fast-growing, but long-lived tree. Range: It range covers most of the northeastern U.S. and southeastern Canada, excluding Nova Scotia. It extends as far west as the Great Plains. It is the most northern Basswood tree. Uses of the American Basswood: Both the Native Americans and the early European settlers had many uses for this tree. This tree provided lumber, medicine, food, and other uses. The wood was used for turnery, veneer, plywood, cabinetry, furniture, coffins, musical instruments, toys, whistles, boxes, crates, kitchenware, food containers, yardsticks, interior trim, and pulp and paper. It takes staining well. However, it makes a poor fuel. The Iroquois Tribe carved ritual false-face masks upon these trees and then removed them to hollow them. If the tree survived this carving, it was believed to have supernatural powers. The inner bark strips were either weighted and soaked under water for 2-4 weeks, were boiled in water and lye (wood ashes), or were pounded. These methods were used to remove some of its soft tissue and its tough bast fibers. Afterwards, these strips were twisted to make rope or thread. This rope was soft on the hands when wet and did not kink when dry. This rope was also stronger than what the Europeans had imported. The soft and silky thread was used in suturing. The inner bark was also used for making nets, brushes, mattings, baskets, bags, shoes, and clothing. The outer bark was used as roof shingles and as covering for wigwams. It contains tannin, which was used for tanning leather. A tea from the inner bark was used for treating lung ailments, kidney stones, gout, heartburn, dysentery, and various stomach troubles. It was also used as a diuretic. A bark poultice was used for treating burns, skin ailments, and for opening boils. Fresh bark was used as a bandage. A tea or tincture from the leaves, flowers, or buds was used for treating nervous headaches, restlessness, high blood pressure, insomnia, respiratory ailments, asthma, epilepsy, and acid indigestion. It was also used as a diaphoretic. However, the flower tea can cause heart damage. A leaf poultice was used for broken bones and swollen areas. A root infusion was used as an anthelminic for treating worms. The wood was made into charcoal and was consumed to treat intestinal disorders. It was also applied externally for treating edema, cellulitis, and ulcers of the lower leg. The flowers were often used as cosmetics. A flower tea in bath water was used as skin treatment, washing hair, and relaxation. The flowers also contain flavonoids (an antioxidant), volatile oils, and mucilaginous substances. The tree’s sap has high sugar content. The sap was used as a beverage or was boiled down to syrup, like Maple (Genus Acer). The leaves contain invert sugar, which is safe for diabetics. The fruits and flowers were ground into a paste that both looks and tastes like chocolate. Unfortunately, this chocolate substitute does not keep well and quickly decomposes. The tiny, young leaves and the closed leaf buds were used in salads or as potherbs. The flowers and flower buds were also used for the same purposes. The leaf buds were chewed as a thirst quencher. The mucilaginous inner bark is also edible. Threats: Basswoods have some weaknesses. Their thin bark is sensitive to fires. They are susceptible to insect attacks, especially from the Japanese Beetles (Popillia japonica Newman). However, they are tolerant of drought and air pollution. REFERENCES MICHIGAN TREES By Burton V. Barnes and Warren H. Wagner, Jr. IDENTIFYING AND HARVESTING EDIBLE AND MEDICINAL PLANTS IN WILD (AND NOT SO WILD) PLACES By “Wildman” Steve Brill with Evelyn Dean THE ENCYCLOPEDIA OF EDIBLE PLANTS OF NORTH AMERICA By Francois Couplan, Ph. D. THE BOOK OF FOREST AND THICKET By John Eastman and Amelia Hansen EDIBLE WILD PLANTS OF EASTERN NORTH AMERICA By Merritt Lyndon Fernald and Alfred Charles Kinsey TREES OF PENNSYLVANIA AND THE NORTHEAST By Charles Fergus and Amelia Hansen EASTERN/CENTRAL MEDICINAL PLANTS AND HERBS By Steven Foster and James A. Duke TREES OF THE EASTERN AND CENTRAL UNITED STATES AND CANADA By William M. Harlow 101 TREES OF INDIANA By Marion T. Jackson NATIONAL WILDLIFE FEDERATION FIELD GUIDE TO TREES OF NORTH AMERICA By Bruce Kershaw, Daniel Mathews, Gil Nelson, and Richard Spellenberg TREES OF ONTARIO By Linda Kershaw DRINKS FROM THE WILDS By Steven A. Krause AUTUMN LEAVES By Ronald Lanner TREES OF THE CENTRAL HARDWOOD FORESTS OF NORTH AMERICA By Donald J. Leopold, William C. McComb, and Robert N. Muller NATIONAL AUDUBON SOCIETY FIELD GUIDE TO NORTH AMERICAN TREES (EASTERN REGION) By Elbert L. Little THE FOLKLORE OF TREES AND SHRUBS By Laura C. Martin NATIVE AMERICAN MEDICINAL PLANTS By Daniel E. Moerman A NATURAL HISTORY OF TREES OF EASTERN AND CENTRAL NORTH AMERICA By Donald Culross Peatties TREES AND SHRUBS By George A. Petrides THE URBAN TREE BOOK By Arthur Plotnik NORTH AMERICAN TREES By Richrad J. Preston, Jr. and Richard R. Braham RED OAKS AND BLACK BIRCHES By Rebecca Rupp OHIO TREES By T. Davis Sydnor and William F. Cowen THE FORAGER’S HARVEST By Samuel Thayer THE USES OF WILD PLANTS By Frank Tozer en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tilia_americana