* Your assessment is very important for improving the work of artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download Unit I: Introduction to Economic Concepts - AP

Survey

Document related concepts

Transcript

AP Government and Economics 2010-11 Reader

Introduction

First: I’d like to congratulate you at reaching this point, only the most dedicated student even attempt to take an AP

class. Hopefully this class will be intellectually rewarding, interesting, and at times even fun.

Second: Don’t panic! This booklet is designed to cover the whole year. If you were given most of your assignments for

any class, it might seem overwhelming. I’ve created this booklet so that you can get ahead, but more importantly so you

can plan your time well. I know that you will have other classes and activities; this is my attempt to give you a way to

manage your time effectively.

Third For those of you who apply for the ACE program for the Second Semester, at the time of creating this reader, I

haven’t quite decided what the additional assignment will be, but don’t worry, it will come to me!

Fourth: You can write in this book, it’s yours. You can underline important passages, make corrections as needed and

make notes in the margins. For the readings, because they are primary sources, spelling was left as it was originally

written, but that doesn’t mean everything is perfect.

Fifth: Don’t get over confident. This is not “everything” that you will be doing this year. You will also be reading,

completing some small assignments, taking notes, reviewing your material, and just plain studying for quizzes and

exams. Additionally, if time is short, I may modify an assignment listed in this reader, especially with the changing

nature of a school day, who knows when we may have a fire drill or a rally to interrupt our perfect plan.

Syllabus Abbreviation Key

Wilson - The APGOV Textbook

Course Unit Topics

General Assignments

Assignments

Multiple Choice Hints

FRQ Rubric

In Class Debates

Study Guides and Notes

Prompted Essay Assignment

Summer Assignment

Semester Bridge Assignment

Online Class Component

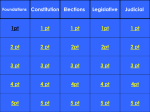

Unit I- Constitutional

Underpinning of the U.S.

Government.

Assessments

Chapter 1 Exam- Multiple

Choice and 1 FRQ

Exam Chapter 2 (25

multiple choice questions 1

FRQ)

Section 1

Unit Exam Chapter 1,2, 3

Multiple Choice and FRQ

Chapter One Study Guide

Basic Politics Simulation

Chapter Two Study Guide

Chapter Three Study Guide

Plato- The Cave

Locke- Two Treaties

AntiFederalist #84

Federalist #51

Federalist #10

Beard- Framing the Constitution

Lawrence and Dorf- How not to read the

Constitution

McCulloch v. Maryland

United States v. Lopez

Unit II-Political Beliefs

and Behaviors

Unit II Exam Ch 4, 5 & 6Multiple Choice and FRQs

Chapter Four Study Guide

Opinion Poll Project

Chapter Five Study Guide

Chapter Six Study Guide

Tocqueville- Democracy in America

Brooks- One Nation Slightly Divisible

Unit III- Political Parties,

Elections

Unit III Exam Ch 7 & 8Multiple Choice

Chapter Seven Study Guide

Chapter Eight Study Guide

Election Project

Jefferson- A Profession of Political Faith

Unit IV- Interest Groups

and Media

Unit IV Exam- Chapters 9

& 10- Three FRQ’s

Chapter Nine Study Guide

Interest Group Project

Chapter Ten Study Guide

Reform the Media Project

Fallows- Why Americans Hate the Media

Page

Unit V- Branches of

GovernmentPart A Congress

Chapter 11 ExamMultiple Choice and One

FRQ

Study Guide for Chapter 11

Article on Congress Essay

Mock Legislation Simulation

Burke- Speech to the Electors of Bristol

Ellwood- In Praise of Pork

Riedl- Nine Thousand Earmarks

Starobin- Pork a Time Honored Tradition

Unit V- Branches of

GovernmentPart B -The Presidency

and the Bureaucracy

Chapter 12 and 13 Exam

Multiple Choice and Two

FRQs

Chapter 12 Study Guide

Chapter 13 Study Guide

Neustadt- Presidential Power and the

Modern President

Weber- Bureaucracy

Unit V- Branches of

GovernmentPart C- The Judiciary

Unit V Exam- Multiple

Choice

Chapter 14 Study Guide

Supreme Court Writing Assignment

Scalia- Liberty and Abortion; A Strict

Constructionist’s View

Unit VI- Policy Making

Economic, Foreign and

Social Policy

Not an error- Ch 20 is

grouped in the Policy unit

Not an error- Ch 21 is

grouped in the Policy unit

Unit Exam Multiple

Choice and FRQs

Chapter 15 Study Guide

Chapter 16 Study Guide

Chapter 17 Study Guide

Chapter 20 Study Guide

Chapter 21 Study Guide

Public Policy Project

Will- Why Didn’t Bush Ask Congress?

Easterbrook- Some Convenient Truths

Unit VII- Civil Liberties

and Civil Rights

Unit IX Exam Ch 18 & 19Multiple Choice and FRQs

Chapter 18 Study Guide

Chapter 19 Study Guide

Supreme Decisions- Civil Rights Project

Williams- Proposition 209

APGOV

Multiple Choice (45 minutes for 60 questions)

1. Don't panic if you come across difficult questions. The test is supposed to have some very hard questions so

they can tell the difference between more and less prepared students.

2. Use at least two go-throughs on the test. On you first run answer only the questions you are sure of. Then

go back and do the other you didn’t know. Often times you will get hints or your memory will be jogged by

the questions you did know.

3. Circle EXCEPT questions so you can remind yourself you are looking for a FALSE statement for the

answer.

4. Do not change an answer unless you are sure it is wrong. Make sure erasers are clear.

5. If a multiple choice question is left blank, no points are deducted. Since a quarter of a point is deducted for

incorrect answers, students should avoid making random guesses. Students may benefit from educated

guesses though.

6. You can and should make marks on the multiple choice test itself in order to keep track of the choices that

they have eliminated.You can write on the test, but not on the answer sheet.

7. Keep your eye on the clock. You have 45 minutes to answer 60 questions. If you have additional time,

double check your answers.

Free-Response (1 hour 45 minutes – 4 questions).

For the AP exam this section accounts for 50% of your overall score. There are four questions – you must answer all

four – which count equally. Because the free-response questions are open-ended, this is your opportunity to

demonstrate your broad understanding of U.S. government and politics. You will be asked to analyze some of the basic

concepts that form the foundation of the American political system. Most questions will ask you to characterize

relationships among various political institutions, their responsibilities, and the consequences of their actions. Some

questions will ask you to analyze both sides of an issue. You will see directives like analyze, assess, evaluate, examine,

and discuss. This means that knowing facts is not enough. You must be able to use facts to construct a thorough and

intelligent response.

1. Understand the Question: READ IT!!! Read and then reread the question for clarity. If it helps, rephrase the question

for clarity. Look for key words such as who, what, when, why, argue argument, explain, and discuss. Know what the

question is asking you. If you are asked to discuss the change in federalism over time, you won’t get full

credit for simply defining federalism. The rest of the answer involves your interpretation of federalism

changing through court cases, new policy, etc. READ THE QUESTION CORRECTLY.

2. Identify the question type

There are generally three types of questions on the exam. The verbs which the question uses will tell you

what kind of question is being asked

I. Write about the meaning of a concept. Key verbs: define, describe, identify, list, state, summarize.

II. Write about both sides of an issue or recognize similarities and differences. You don’t need a full

thesis statement to answer these questions because your not asked to take a position and argue for it,

however, you do need an organizing statement to orient the reader to the answer. Key verbs: compare,

contrast, discuss, explain, and illustrate.

III. Write about a position and argue for a specific point of view. A thesis statement is require for

this type of question. Key verbs: analyze, argue, and interpret.

3. Which path do I take?

Often times, FRQ’s will ask you to come up with several concepts and then to elaborate on them. They might

ask for “two reasons” or “three examples.” However, there is often 7 or 8 possible right answers. Therefore,

before you write, make a list of all possible answers that you know could work. Then, choose the ones that

you feel most comfortable writing about. HINT – AP readers do not penalize you for wrong answers, only

missing answers. Therefore, if they ask for “two examples,” then give three examples because it will give you

another possibility of getting points if your other answers missed the mark.. Aim for three pieces of supporting

evidence in your response. Three examples are just enough to prove your point. Any more than this will read too much

like a list and will detract from your essay and could cost you points.

4. Do I need an introduction?

Does the question ask you to take a position? If so, take one. Don’t sit in the middle, argue one side because

they don’t care which side you argue. They only care that your argument works. ONLY WRITE AN INTRO

IF THEY ASK YOU TO TAKE A DEFINITE STAND. Introductions in an other situation is a waste of time.

5. Format? Formulate and outline. Some questions are multiple-portioned and it will help to formulate an outline in

order to properly answer the entire question. Answers to some questions, even if they are multiple-portioned, might be

answered better in a more traditional format, with each paragraph addressing a piece of evidence. It may help to use

this basic outline format:

Paragraph 1: your position or interpretation of the given information.

Paragraph 2: your first piece of evidence and any supporting details. (The details can be in bullet form)

Paragraph 3: your second piece of evidence and any supporting details.

Paragraph 4: your third piece of evidence and any supporting details.

Paragraph 5: summary of your points and restatement of your position.

The example below is a good way to think about answering most FRQs. It is very mechanical in that you number your

answers, and it is also easy on the reader, which they will appreciate. ALWAYS WRITE LEGIBLY IN BLUE OR

BLACK PEN.

Sample Response from the 2005 Exam

Question: Explain how two factors keep the United States Supreme Court from deviating too far from public

opinion. (AP accepted 6 possible answers)

1. Presidents nominate Supreme Court justices so they can’t deviate too far from public opinion. Since the

president is elected, the general public shares his opinion on a lot of issues. When there is an opening on the

court, the President wants to make a choice that the people agree with, especially if he plans to run for reelection. If he nominates a person who deviates too far from public opinion, there will be a backlash in his

approval ratings.

2. Supreme Court rulings can be overruled with new laws or constitutional amendments so they can’t deviate

too far from public opinion. The members of Congress are responsible to the people, so they must guarantee

that law follows public opinion if they hope to be reelected.

6. Re-read your answers

Students always are in a rush to turn in their tests, but if you have to sit in the room for 100 minutes anyway,

why not re-read your answers? Each question is scored independently. Therefore, you will not be able to “make up”

points on questions that you feel you did not answer well by overcompensating. Go back and make sure you

answered each question fully. If you did not, you can write more at the end, and then draw an arrow to the

appropriate place where the information belongs.

General Tips

Give concrete examples. Specific examples of your answers help solidify your answers.

Answer all part of the question. Exam graders will reward students for more for answering all parts of

the question than for doing well on only one part.

Understand what you are being asked before you start writing.

Don’t panic and start making things up. It is better to just make a brainstorm list and you might get

lucky and stumble across a right answer.

Do’s and Don’ts of the FRQ

Do’s

Write as neatly as possible. If they can’t read it, they can’t grade it. Neatly draw a line through a mistake,

write correct information above.

Read the question. Then read the question again. Make sure you’re answering only what is being asked.

Reread your work if you have time. Make sure you LINK THE QUESTION TO THE ANSWER!

There is no penalty for wrong information, so write as much as you can. If they ask for two examples,

give three.

Use the EXACT VOCABULARY from the question in each component of your answer. Most rubrics ask

for linkage back to the question. This is the sure fire way to move in that direction.

Don’ts

1. Don’t give personal opinions (like your political affiliation or whether you like the president’s policy).

The exam tests your knowledge of political process, not opinion.

2. Don’t give long, unnecessary introductions, get right to the point.

3. Don’t give information they didn’t ask for. There are no extra credit or “brownie” points.

4. Don’t spend more than 25 minutes on any free response question.

5. Don’t fall asleep. Fight the fatigue. Time is generally not a factor. Do not look back and think about

how you wasted it because your were tired, bored, or indifferent. Bring a strong peppermint to the

test. This will jolt you awake, and stimulate your senses.

Scoring and Credit

The raw scores of the exam are converted into the following five-point scale:

5 - Extremely well qualified

4 – Well qualified

3 – Qualified

2 – Possibly qualified

1 – No recommendation

FRQ Rubric

Points given will be indicated on the left, and the reasoning behind the points circled on the chart below.

Points

5

4

3

2

1

0

AP

Rating

9-8

7-6

5-4

3-2

1

0

Thesis

Organization

Balance

Analysis

Evidence

Errors

Superior thesis Explicit and fully

responsive to the

question.

Extremely wellorganized- Essay

organization is

clear, consistently

followed, and

effective in

support of the

argument

Addresses all areas

of the prompt

evenly. If the

question requires

multiple arguments.

at least three ideas

are all covered at

some length

Excellent use

of analysis to

support thesis

and main

ideas.

All major assertions

in the essay are

supported by at least

three specific ideas,

events, or

individuals being

used as relevant

evidence

Extremely wellwritten essay

Strong thesis Explicit and

responsive to the

question,

contains general

analysis

Well-organized

essay – Essay

organization is

clear, effective in

support of the

argument, but not

consistently

followed, tends to

generalize.

Addresses all areas

of the prompt; may

lack some balance

between major areas.

Strong

analysis in

most areas;

needs more

detail.

All major assertions

in the essay are

supported by more

than one specific

ideas, events, or

individuals being

used as relevant

evidence

Well-written essay

Most of the major

assertions in the

essay are supported

by at least one

specific ideas,

events, or

individuals being

used as relevant

evidence

Good Essay

Only one or two

specific ideas,

events, or

individuals are

mentioned, but little

to no use as relevant

evidence

Adequate Essay,

but is somewhat

incomplete (too

short)

Essay is

incomplete

Little to no

relevant facts

No specific ideas,

events, or

individuals are

mentioned or used.

No analysis

No evidence

Clear thesisThesis is explicit,

but not fully

responsive to the

question, tends to

stylistically

wander before

reaching the core

argument to be

addressed.

Organization is

clear, consistently

followed, but not

effective

Underdeveloped

Thesis- Thesis

that merely

repeats/

paraphrases the

prompt

Organization is

unclear and

ineffective, tends

to jump

chronologically.

No discernable

attempt at a

thesis

No discernable

organization;

stylistically

wanders and

jumps

chronologically.

Little to no effort

shown

Thesis is off

topic.

If the question

requires multiple

arguments at least

three ideas suggested

by the prompt are

covered at least

briefly

Essay shows some

imbalance; there is a

discussion of ideas,

but generalized

arguments.

Some

important

information

left out

Contains some

analysis; much

more detail is

needed.

Important

information

left out.

Essay shows serious

imbalance, If the

question requires

multiple arguments.

less than three

specific ideas,

events, or

individuals being

used are discussed,

and only briefly.

Only one or no

arguments are

mentioned

No arguments

mentioned

Lacks analysis

of key issues

Most major

events omitted

No analysis

____ Introduction contains vague or “wasted” sentences

____ Essay contains vague statements or generalizations not supported by facts.

____ Essay attempted to tell a story rather than relaying facts.

____ Essay attempted to validate your personal opinion, rather than answering the prompt.

____ Don’t use “I” or “my” statements

____ Don’t connect issues to “today” (unless asked)

____ Don’t use “flowery” or slang style writing

____ Poor spelling and grammar

____ Poor penmanship: essay difficult to read

The errors that

exist do not detract

from the argument

May contain an

error that detracts

from the argument

such as the wrong

chronology,

associating the

ideas of one figure

with another.

Contains a few

errors that detract

from the argument,

Contains several

errors that detract

from the argument,

Contains numerous

errors that detract

from the argument

Completely

incorrect or not

turned in.

OBJECTIVE: Students in this AP section are required to deliver a formal debate to their class. This requirement may be met by an individual debate (one-on-one),

2v2, or 3v3. Each student will be required to address the class for a period of at least 4-7 minutes. During this time the students will debate issues relating to US

Government.

GRADING THE DEBATE: SEE ATTACHED

STRUCTURE AND CONTENT OF THE FORMAL DEBATE: Students will be divided into two teams; an affirmative team, that will debate/defend the

resolution and a negative team that will oppose the resolution. Each side will research their position gathering facts, data, and other information to their position.

Students will be encouraged to use a variety of sources including information from the library, public institutions (public libraries, local universities), and the

internet. The structure of the debate is as follows:

5 minutes Affirmative Original Construction of the argument:

During this time period the affirmative side will present the major arguments

supporting the resolution based upon the research.

Name: __________________

4 Minutes Cross examination:

During this period the Negative may ask the Affirmative questions of

clarification.

Name: __________________

5 Minutes Negative Original Construction of the argument:

During this period the Negative side will present the major arguments against

the resolution based upon the research.

Name: __________________

4 Minutes Cross Examination:

During this time the Affirmative may ask the Negative questions of

clarification.

Name: __________________

4 Minutes Affirmative Rebuttal:

During this time the Affirmative may challenge the validity of the Negative's original argument. This can be done by introducing

information to counter the points made by the Negative side.

Name: __________________

5 Minutes Negative Rebuttal:

During this period the Negative may offer information to counter any points

brought up during Affirmative's original argument, defend points brought up

during Negative's original argument, defend points raised by Affirmative

rebuttal, and restate their original argument.

Name: __________________

1 Minute Affirmative Rebuttal:

During this time period the Affirmative may rebuttal any of the Negative's

major arguments and sum up their position.

Name: __________________

Original Construction of Argument Speeches: Speeches will allow the Affirmative and Negative speakers to offer evidence in support of their position in addition

to disprove the arguments offered by the opponent. In the original construction speech the student will research the resolution and create arguments in support of

their position.

HINTS:

1) 2-3 main points

3) Anticipate the other side

5) Talking is better than reading: personal experience

6) Strong opening and closing sentences

2) Have a road map

4) Quotes for support (but don’t overdo it)

7) USE note cards, do not read an ESSAY

Rebuttal Speeches: Serve as an opportunity to clarify the issues presented in the debate and to question the evidence presented by the other side. This is best done

by gathering information that rivals or contradicts the other side. The focus of a rebuttal speech should be only to address the information presented by the other

side. No new topics should be introduced.

Time Limits and Visual Aids: All time limits have an extended grace period of up to 15 seconds for each speech. This applies to speeches that go over the limit,

not those that are too brief. There will be a 3-5 minute question and answer period following each debate to allow the class members or instructor to participate by

questioning the speaker and/or discuss the information presented. Visual aids are optional but a good idea. The debates will be presented in front of the classroom,

with the speakers standing when presenting and addressing the audience as well as the opponent. FORMAL ATTIRE IS REQUIRED!

DEBATE TOPICS: To be completed over the course of the semester . Groups of no more than 3

students!

Constitutional Underpinnings

The Federal government has been devolving more power to the states. This trend is positive because it

allows states to better meet the individual needs of their citizens.

Political Beliefs and Behavior

Low voter turnout among people threatens democracy in America.

Because of political apathy among young people, their issues are not adequately addressed.

Political Parties and Interest Groups

Interest groups, PACs, and 527s have too much clout in shaping public policy.

Multi-party political systems more effectively represent citizen interests than does the American two-party

system.

Institutions/Three Branches of Government The Supreme Court is too heavily influenced by politics.

The United States should reduce the number of regulatory agencies, because they generate red tape, raise

prices, and reduce competitiveness in the world market.

Judicial review is undemocratic. It permits non-elected judges to decide whether or not a law is

constitutional. It can frustrate the intentions of democratic governments by overruling the actions of

elected officials.

The president has become so powerful that there is no longer an effective balance of powers.

Public Policy

The Congressional committee system gives too much power to the majority party in setting the political

agenda. As a result, the views of the minority party are ignored.

Civil Liberties and Civil Rights—

Affirmative Action programs are necessary to safeguard equal opportunity in both education and

employment for minorities.

In the interest of public safety, the Fourth Amendment rights of those under the age of 18 should be

severely limited.

Student Critique Form

YOUR NAME:________________________________________________________

DEBATE TOPIC:______________________________________________________

TEAM BEING CRITIQUED:____________________________________________

Positive aspects of opening statement:

How opening could have been improved:

Were the questions clear and focused? Did they challenge the opponent's position?

Did the debaters directly and persuasively respond to questions?

Positive aspects of closing statement:

How closing could have been improved:

How effective was the use of statistics?

How effective was the use of quotations?

What would have improved this debate?

What did these debaters do best?

Debate Grade Sheet

DEBATE TOPIC:

POSITION/STANCE:

TEAM BEING GRADED: 1. _________________________ 2.

___/15 OPENING STATEMENT

TIME: ________

___/10 DIRECT QUESTIONING

TIME: ________

___/15 CLOSING STATEMENT

TIME: ________

___/10 RESPONSE TO QUESTIONING

___/10 USE OF STATISTICS/QUOTATIONS

___/5 ENNUNCIATION, VOLUME, ETC.

___/5 DRESS AND APPEARANCE

___/70 Total

3.

APGOV Study Guide and Note-taking Assignment

For APGOV the college board has broken the course into six major themes:

I. Constitutional Underpinnings of United States Government

II. Political Beliefs and Behaviors

III. Political Parties, Interest Groups, and Mass Media

IV. Institutions of National Government

V. Public Policy

VI . Civil Rights and Civil Liberties

Even though there are less major units than APUSH or APEH, there is still a great deal of information to learn

for this course. This assignment will be the method you will use to organize the course content and how I will

keep you accountable for keeping pace with the reading. I will check your notes on exam days.

For each chapter, you will have a series of questions in a study guide. These study guides will be due on the

day of the chapter or unit exam. In order to be efficient with our time in class, you will have to do some

reading and notetaking at home. Here is the format for notes for APGOV.

For most note taking, the typical Cornell note system follows this format:

1. Record: During the lecture, use the note taking column to record the lecture using telegraphic sentences.

2. Questions: As soon after class as possible, formulate questions based on the notes in the right-hand column.

Writing questions helps to clarify meanings, reveal relationships, establish continuity, and strengthen memory.

Also, the writing of questions sets up a perfect stage for exam-studying later.

3. Recite: Cover the note taking column with a sheet of paper. Then, looking at the questions or cue-words in the

question and cue column only, say aloud, in your own words, the answers to the questions, facts, or ideas

indicated by the cue-words.

4. Reflect: Reflect on the material by asking yourself questions, for example: “What’s the significance of these

facts? What principle are they based on? How can I apply them? How do they fit in with what I already know?

What’s beyond them?

5. Review: Spend at least ten minutes every week reviewing all your previous notes. If you do, you’ll retain a

great deal for current use, as well as, for the exam.

For the notes that I give you in class, or my powerpoints via the web page, they should be written on the right hand side

of your note sheet as you would on typical Cornell notes. For the left hand side however, I would like you to “Enhance”

your notes. What I am looking for, is that you go through the chapter and that you add anything I may have missed,

specficially incorporating the list of terms included on each study guide. Most of the terms are included in the chapter,

but others are not. These terms become important for two major reasons:

1. They serve as the basis of information for many of your multiple choice exams

2. They serve as factual hooks that you can use in your FRQ essays.

For the question area of your notes, you should indicate as you review your notes, which themes did the particular topic,

person, or event address? You could streamline your note-taking with symbols, numbers or letters indicating which part

or parts relates to the PERSIA acronym. This will help with your overall review of your notes.

APGOV Note Organization

Your notes should have the following parts

Enhanced Notes: Notes you have added to the Core Notes

Chapter Terms

Core Notes: Notes provided by Guemmer

Your Notes should look something like this:

APGOV Note Sheet

Enhanced Notes

_________________________________

_________________________________

_________________________________

_________________________________

_________________________________

_________________________________

_________________________________

_________________________________

_________________________________

_________________________________

_________________________________

_________________________________

_________________________________

_________________________________

_________________________________

_________________________________

Summary

Core Notes

______________________________________________

______________________________________________

______________________________________________

______________________________________________

______________________________________________

______________________________________________

______________________________________________

______________________________________________

______________________________________________

______________________________________________

______________________________________________

______________________________________________

______________________________________________

______________________________________________

______________________________________________

______________________________________________

______________________________________________

______________________________________________

______________________________________________

______________________________________________

______________________________________________

______________________________________________

______________________________________________

______________________________________________

______________________________________________

______________________________________________

______________________________________________

______________________________________________

______________________________________________

______________________________________________

______________________________________________

______________________________________________

______________________________________________

______________________________________________

______________________________________________

Prompted Essay Assignment

In a democracy the free flow of opinions is critical for a vital government. To be an active member of society,

you need to be able to express your opinion in an informed way.

The assignment: Choose eight of the following prompts, and write a 5 paragraph persuasive essay for each of

your chosen prompts. Choose a position either pro or con to argue.

Each essay is worth 20 points, and will be graded on the strength of your arguments and the clarity of your

writing. Each prompted essay will be due every week throughout the term on Fridays, unless there is no

Friday that week, in that case they will be due on Thursday. These essays will be due on the day assigned and

will not be accepted late, except in the case of a legitimate medical absence. Individuals who are participating

in athletic events are still obligated to turn their essays in on the due date.

1. A just government ought to value the redistribution of wealth over property rights.

2. In the US, the use of race as a deciding factor in college admissions is just.

3. As general principle, individuals have an obligation to value the common good above their own

interests

4. Individual claims of privacy ought to be valued above competing claims of societal welfare.

5. The US has a moral obligation to promote democratic ideals in other nations.

6. The government’s obligation to protect the environment ought to take precedence over its obligation

to promote economic development.

7. Even if disclosure is legally permissible, journalists have an ethical obligation to limit material

released to the public.

8. A just society ought to value the legal rights of people with mental illness above its obligation to

protect itself.

9. The US has a moral obligation to mitigate international conflicts

10. A society has a moral obligation to redress its historical injustices, such as slavery.

11. When in conflict a business' responsibility to itself ought to be valued above responsibility to

society.

12. In the US Judicial system, truth seeking ought to take precedence over privileged communication

13. In the near future we will be able to build robots that are as intelligent and powerful as humans, and

will therefore have the ability to take over from humans. We should therefore stop conducting

research into robotic intelligence.

14. Should voting in elections be compulsory?

15. The US Constitution prohibits people originally from other countries from being President, and

should be amended to change this

16. The constitutional limit preventing US Presidents from serving more than two terms should be

repealed

17. Young people should be subjected to night-time curfews as a way to reduce crime

18. America should change its Immigration Policy, so children born to illegal immigrants would not

automatically become citizens.

19. The United States federal government should substantially decrease its authority either to detain

without charge or to search without probable cause in the name of national security.

20. The Federal Government should punish states that knowingly attempt to violate Federal Drug laws.

21. Congress should establish English as the national language

22. The government should set minimum education standards as part of voting rights

23. The state of California should be split into two or three parts in order to govern it more efficiently

24. The Federal government should create national identity cards in order to eliminate the problem of

illegal immigration and terrorism in the United States.

25. Teenagers who commit a felony should be charged and tried as adults.

26. California high schools should adopt a statewide uniform dress code in order to eliminate

inappropriate attire.

27. Private businesses should have the right to ban cell phone signals.

28. The age to vote should be raised to the drinking age in order to be more consistent

29. The U.S. should reinstitute a military draft

30. Restrictions on stem cell research should be eliminated in order research cures for neurological

diseases such as Parkinson’s

31. The United States should limit its involvement in international conflicts to those countries that pose

an economic or military threat.

32. Congress should reinstitute the “Fairness Doctrine” on broadcast media.

33. Corporal punishment should be reinstituted in California schools to improve student discipline.

34. The California High School Exit Exam should be expanded to include science and history

35. The California government should allow private corporations to manage their prisons like other

states allow.

ATTENTION !!!

ARE YOU READING THIS !!

THE SUMMER ASSIGNMENT IS ONLY FOR STUDENTS WHO ARE ENROLLED IN THE FIRST AND

THIRD TERM CLASS. !!!

Summer 2010 Assignments

AP Government with Economics

A.P. Government requires different thinking and writing skills than you used in U.S. History. Writing for government

requires the understanding and analysis of abstract concepts and principles. You will depend less on recitation of facts

than on your interpretation of the facts. That means those of you who basically bluffed your way through World and US

History by knowing a laundry list of terms and dates will have to change your methodology.

With the current state of our government and economy, both on a national and a local level, we will be watching the

political battles for spending and foreign policy initiatives unfold. Throughout the year you will become aware of

politics and economics in general and specifically, have an opportunity to explore your own political and economic

ideologies.

This summer assignment is designed to help you to transition from thinking historically to thinking and writing from a

political and economic perspective. There are four parts to this assignment and each part is described below.

Assignments will be due the first day of class.

ASSIGNMENT # 1: Follow the News

Your first assignment is to read the newspaper, weekly news magazines, the internet news sources, and/or the nightly

network news. Keep track of the major news stories that are national or international in scope. (You may want to keep a

journal with a few sentences about the stories) This assignment does not require that you turn in anything but you will

have a quiz on the important big news events of the summer. This will be good practice for the regular news quizzes

you will have throughout the year.

ASSIGNMENT # 2: Comparison Essay (Relating to Smith and Marx/Engels readings)

These two documents have completely opposite views on the role of the market in society. In a comparative essayWhat does Adam Smith say a free market provides to society? What does Marx/Engels say a free market does to

society? Also, how is change accomplished in society according to Adam Smith? What has to occur to create change

for Marx/Engels?

Most students will be required to write a comparative essay at some point in their academic career. A comparative

essay is an academic paper which compares two or more topics, items, concepts, and more. Comparative essays seek to

discuss how items or concepts are similar, not how they are different.

Comparative essays are generally easy to write and should follow the same basic paper structure as any other academic

writing assignment. A comparative essay should have an introduction, a paper body, and a conclusion. The introduction

part of the paper should introduce the topic and should contain a thesis statement which will be supported throughout

the remainder of the paper.

The body of the paper is where the student should discuss the similarities of the items being compared. Although a

comparative essay is intended to primarily discuss the how items are similar, there can be some, very basic, references

to what makes the items different. However, it is imperative that students keep discussions of differences to a minimum

because then the paper becomes a compare and contrast essay instead of a comparative essay.

The conclusion of the comparative essay is where students should restate the thesis and wrap up the discussion. This is

generally where comparative essays give students trouble. It’s difficult to know when to stop comparing. It is not

necessary to compare each and every factor of the items or concepts in the paper. Students should select how many

comparisons to make based on the length of the paper.

For instance, in a one-page paper, students might want to select the number of comparisons based on the number of

body paragraphs. Since a one-page comparative essay generally has one introduction paragraph, three body paragraphs,

and one conclusion paragraph, the student might want to highlight three short comparisons, one per body paragraph, or

one in-depth comparison to discuss throughout the entire three body paragraphs. Longer papers invite longer discussions

and more comparisons.

Finally, comparative essays should follow the basic rules of paper writing. Students should proof their papers to ensure

that they have followed the citation guidelines given to them by the instructor. The paper should also be proofed for

grammar, spelling, and punctuation errors. Paragraphs should hold complete thoughts and the paper should be solid and

well-written to ensure the best grade possible.

Your essay should be 1-2 pages, typed using Times New Roman 12 point font, double spaced. If you use a specific

quote, indicate (Author) following the quote.

ASSIGNMENT # 3: Textbook Reading and Review: Read and review the first two chapters of the Economics

Textbook, you can also refer to the Introduction to Economics notes I have available online. You must have them read

and reviewed thoroughly enough to prepare for the Chapter 1 and 2 Test on the second day of the semester.

Additionally, the terms in the two chapters will help you with the last portion of the summer assignment. You can find

the Chapter 1 and 2 Term list in Unit I of the Economics Section toward the end of this reader. By completing the first

couple of chapters during the summer, it allows for some additional time to cover both more Economics and US

Government this year.

Assignment # 4: Local Business Project- Refer to the specific assignment sheet found in Unit I of the Economics

Section.

TITLE: Adam Smith and the Origin of Capitalism

SUBTITLE::

SOURCE:: Excerpt and condensation of Chapter 4 from The Worldly Philosophers: The Lives, Times, and Ideas of the

Great Economic Thinkers by Robert L. Heilbroner, 7th ed., 1999.

COPYRIGHT::

TAGS:: Adam Smith, Smith, The Wealth of Nations, capitalism, market, markets,

free market, system of perfect liberty, liberty and profit, self interest, competition

COUNTRIES:: Europe

YEARS:: 1776-1800

INTRO:: Robert Heilbroner's The Worldly Philosophers is a uniquely readable introduction to the lives and ideas of the

great economic theorists of the last three centuries. The book has enlivened the study of economics for beginning

students for more than 40 years. Adam Smith published his Inquiry into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations

in 1776, adding a second revolutionary event to that fateful year. A political democracy was born on one side of the

ocean; an economic blueprint was unfolded on the other. But while not all Europe followed America's political lead,

after Smith had displayed the first true tableau of modern society, all the Western world became the world of Adam

Smith: his vision became the prescription for the spectacles of generations. Adam Smith would never have thought of

himself as a revolutionist; he was only explaining what to him was very clear sensible, and conservative. But he gave

the world the image of itself for which it had been searching. After The Wealth of Nations, men began to see the world

about themselves with new eyes; they saw how the tasks they did fitted into the whole of society, and they saw that

society as a whole was proceeding at a majestic pace toward a distant but clearly visible goal. In a word, a new vision

had come into

being. What was that new vision? As we might expect, it was not a State but a System -- more precisely, a System of

Perfect Liberty. Smith's vision is like a blueprint for a whole new mode of social organization, a mode called Political

Economy, or, in today's terminology, economics.

The Laws of the Market

At the center of this blueprint are the solutions to two problems that absorb Smith's attention. First, he is interested in

laying bare the mechanism by which society hangs together. How is it possible for a community in which everyone is

busily following his self-interest not to fly apart from sheer centrifugal force? What is it that guides each individual's

private business so that it conforms to the needs of the group? With no central planning authority and no steadying

influence of age-old tradition, how does

society manage to get those tasks done which are necessary for survival?

These questions lead Smith to a formulation of the laws of the market. What he sought was "the invisible hand," as he

called it, whereby "the private interests and passions of men" are led in the direction "which is most agreeable to the

interest of the whole society."

But the laws of the market will be only a part of Smith's inquiry. There is another question that interests him: whither

society? The laws of the market are like the laws that explain how a spinning top stays upright; but there is also the

question of whether the top, by virtue of its spinning, will be moved along the table.

To Smith and the great economists who followed him, society is not conceived as a static achievement of mankind

which will go on reproducing itself, unchanged and unchanging, from one generation to the next. On the contrary,

society is seen as an organism that has its own life history. Indeed, in its entirety The Wealth of Nations is a great

treatise on history, explaining how "the system of perfect

liberty" (also called "the system of natural liberty") -- the way Smith referred to commercial capitalism -- came into

being, as well as how it worked.

Adam Smith's laws of the market are basically simple. They tell us that the outcome of a certain kind of behavior in a

certain social framework will bring about perfectly definite and foreseeable results. Specifically they show us how the

drive of individual self-interest in an environment of similarly motivated individuals will result in competition; and they

further demonstrate how competition will result in the provision of those goods that society wants, in the quantities that

society desires,

and at the prices society is prepared to pay.

But self-interest is only half the picture. It drives men to action. Something else must prevent the pushing of profit

hungry individuals from holding society up to exorbitant ransom. This regulator is competition, the conflict of the selfinterested actors on the marketplace. A man who permits his self-interest to run away with him will find that

competitors have slipped in to take his trade away. Thus the selfish motives of men are transmuted by interaction to

yield the most unexpected of results: social harmony.

But the laws of the market do more than impose a competitive price on products. They also see to it that the producers

of society heed society's demands for the quantities of goods it wants. Let us suppose that consumers decide they want

more gloves than are being turned out, and fewer shoes. Accordingly the public will scramble for the stock of gloves on

the market, while the shoe business will be dull. As a result glove prices will tend to rise, and shoe prices will tend to

fall. But as glove

prices rise, profits in the glove industry will rise, too; and as shoe prices fall, profits in shoe manufacture will slump.

Again self-interest will step in to right the balance. Workers will be released from the shoe business as shoe factories

contract their output; they will move to the glove business, where business is booming. The result is quite obvious:

glove production will rise and shoe production fall.

Through the mechanism of the market, society will have changed the allocation of its elements of production to fit its

new desires. Yet no one has issued a dictum, and no planning authority has established schedules of output. Self-interest

and competition, acting one against the other, have accomplished the transition.

And one final accomplishment. Just as the market regulates both prices and quantities of goods according to the final

arbiter of public demand, so it also regulates the incomes of those who cooperate to produce those goods. If profits in

one line of business are unduly large, there will be a rush of other businessmen into that field until competition has

lowered surpluses. If wages are out of line in one kind of work, there will be a rush of men into the favored occupation

until it pays no more than comparable jobs of that degree of skill and training. Conversely, if profits or wages are too

low in one trade area, there will be an exodus of capital and labor until the supply is better adjusted to the demand.

All this may seem somewhat elementary. But consider what Adam Smith has done, he has found in the mechanism of

the market a self-regulating system for society's orderly provisioning.

Does the world really work this way? To a very real degree it did in the days of Adam Smith. Business was competitive,

the average factory was small, prices did rise and fall as demand ebbed and rose, and changes in prices did invoke

changes in output and occupation.

And today? Does the competitive market mechanism still operate?

This is not a question to which it is possible to give a simple answer. The nature of the market has changed vastly since

the 18th century. We no longer live in a world of atomistic competition in which no man can afford to swim against the

current. Today's market mechanism is characterized by the huge size of its participants: giant corporations and strong

labor unions obviously do not behave as if they were individual proprietors and workers. Their very bulk enables them

to stand out against

the pressures of competition, to disregard price signals, and to consider what their self-interest shall be in the long run

rather than in the immediate press of each day's buying and selling. That these factors have weakened the guiding

function of the market mechanism is apparent. But for all the attributes of modern-day economic society, the great

forces of self-interest and competition, however watered down or hedged about, still provide basic rules of behavior that

no participant in a market system can afford to disregard entirely. Although the world in which we live is not that of

Adam Smith, the laws of the market can still be discerned if we study its operations....

Smith's View of Economic Growth

"No society can surely be flourishing and happy, of which by far the greater part of the numbers are poor and

miserable," he wrote. And not only did he have the temerity to make so radical a statement, but he proceeded to

demonstrate that society was in fact constantly improving; that it was being propelled, willy-nilly, toward a positive

goal. It was not moving because anyone willed it to, or because

Parliament might pass laws, or England win a battle. It moved because there was a concealed dynamic beneath the

surface of things which powered the social whole like an enormous engine.

For one salient fact struck Adam Smith as he looked at the English scene. This was the tremendous gain in productivity

which sprang from the minute division and specialization of labor.

There is hardly any need to point out how infinitely more complex present-day production methods are than those of the

18th century. Smith was sufficiently impressed with a small factory of ten people to write about it; what would he have

thought of one employing ten thousand! But the great gift of the division of labor lies in its capacity to increase what

Smith calls "that universal opulence which extends

itself to the lowest ranks of the people." That universal opulence of the 18th century looks like a grim existence from

our modern vantage point. But if we view the matter in its historical perspective , it is clear that, mean as his existence

was, it constituted a considerable advance.

What is it that drives society to this wonderful multiplication of wealth and riches? Partly it is the market mechanism

itself, for the market harnesses man's creative powers in a milieu that encourages him, even forces him, to invent,

innovate, expand, take risks. But there are more fundamental pressures behind the restless activity of the market. In fact,

Smith sees two deep-seated laws of behavior which propel the market system in an ascending spiral of productivity.

The first of these is the Law of Accumulation. The object of the great majority of the rising capitalists was first, last, and

always, to accumulate their savings. But Adam Smith did not approve of accumulation for accumulation's sake. He was,

after all, a philosopher, with a philosopher's disdain for the vanity of riches. Rather, in the accumulation of capital Smith

saw a vast benefit to society. For capital -- if put to use in machinery -- provided just that wonderful division of labor

which multiplies

man's productive energy. Accumulate and the world will benefit, says Smith. But here is a difficulty: accumulation

would soon lead to a situation where further accumulation would be impossible. For accumulation meant more

machinery, and more machinery meant more demand for workmen. And this in turn would sooner or later lead to higher

and higher wages, until profits -- the source of accumulation -- were eaten away. How is this hurdle surmounted?

It is surmounted by the second great law of the system: the Law of Population. To Adam Smith, laborers, like any other

commodity, could be produced according to the demand. If wages were high, the number of workpeople would

multiply; if wages fell, the numbers of the working class would decrease. Smith put it bluntly: "... the demand for men,

like that for any other commodity, necessarily regulates the production of men."

If the first effect of accumulation would be to raise the wages of the working class, this in turn would bring about an

increase in the number of workers. And now the market mechanism takes over. Just as higher prices on the market will

bring about a larger production of gloves and the larger number of gloves in turn press down the higher prices of gloves,

so higher wages will bring about a larger number of workers, and the increase in their numbers will set up a reverse

pressure on the level of their

wages.

And this meant that accumulation might go safely on. The rise in wages which it caused and which threatened to make

further accumulation unprofitable is tempered by the rise in population. Smith has constructed for society a giant

endless chain. As regularly and as inevitably as a series of interlocked mathematical propositions, society is started on

an upward march. From any starting point the probing

mechanism of the market first equalizes the returns to labor and capital in all their different uses, sees to it that those

commodities demanded are produced in the right quantities, and further ensures that prices for commodities are

constantly competed down to their costs of production. But further than this, society is dynamic. From its starting point

accumulation of wealth will take place, and this accumulation will result in increased facilities for production and in a

greater division of labor.

This is no business cycle that Smith describes. It is a long-term process, a secular evolution. And it is wonderfully

certain. Provided only that the market mechanism is not tampered with, everything is inexorably determined by the

preceding link. A vast reciprocating machinery is set up with all of society inside it: only the tastes of the public -- to

guide producers -- and the actual physical resources of the nation are outside the chain of cause and effect.

But observe that what is foreseen is not an unbounded improvement of affairs. There will assuredly be a long period of

what we call economic growth but the improvement has its limits. In the very long run, well beyond the horizon, he saw

that a growing population would push wages back to their "natural" level. Growth would come to an end when the

economy had extended its boundaries to their limits, and then fully utilized its increased economic "space."

Smith did not see the organizational and technological core of the division of labor as a self-generating process of

change, but as a discrete advance that would impart its stimulus and then disappear. For all its optimistic boldness,

Smith's vision is bounded, careful, sober -- for the long run, even sobering.

No wonder, then, that the book took hold slowly. It was not until 1800 that the book achieved full recognition. By that

time it had gone through nine English editions and had found its way to Europe and America. Its protagonists came

from an unexpected quarter. They were the rising capitalist class excoriated for its "mean rapacity." AII this was ignored

in favor of the great point that Smith made in his inquiry: let the market alone.

In Smith's panegyric of a free and unfettered market the rising industrialists found the theoretical justification they

needed to block the first government attempts to remedy the scandalous conditions of the times. For Smith's theory does

unquestionably lead to a doctrine of laissez-faire. To Adam Smith the least government is certainly the best:

governments are spendthrift, irresponsible, and unproductive. And yet Adam Smith is not necessarily opposed to

government action that has as its end the promotion of the general welfare.

Government's Economic Role

Smith specifically stresses three things that government should do in a society of natural liberty. First, it should protect

that society against "the violence and invasion of other societies. Second, it should provide an "exact administration of

justice" for all citizens. And third, government has the duty of "erecting and maintaining those public institutions and

those public works which may be in the highest degree advantageous to a great society," but which "are of such a nature

that the profit could never repay the expense to any individual or small number of individuals." Put into today's

language, Smith explicitly recognizes the usefulness of public investment for projects that cannot be undertaken by the

private sector – he mentions roads and education as two examples.

What Smith is against is the meddling of the government with the market mechanism. He is against restraints on imports

and bounties on exports, against government laws that shelter industry from competition, and against government

spending for unproductive ends. These activities of the government all bear against the proper working of the market

system. Smith never faced the problem that was to cause such intellectual agony for later generations of whether the

government is

weakening or strengthening that system when it steps in with welfare legislation.

The Danger of Monopoly

The great enemy to Adam Smith's system is not so much government per se as monopoly in any form. The trouble with

such goings-on is not so much that they are morally reprehensible in themselves -- they are, after all, only the inevitable

consequence of man's self-interest -- as that they impede the fluid working of the market. Whatever interferes with the

market does so only at the expense of the true wealth of the nation.

In a sense the vision of Adam Smith is a testimony to the 18th-century belief in the inevitable triumph of rationality and

order over arbitrariness and chaos. Don't try to do good, says Smith. Let good emerge as the by-product of selfishness.

Smith was the economist of pre-industrial capitalism; he did not live to see the market system threatened by enormous

enterprises; or his laws of accumulation and population upset by sociological developments fifty years off. When Smith

lived and wrote, there had not yet been a recognizable phenomenon that might be called a "business cycle." The world

he wrote about actually existed, and his systematization of it provides a brilliant analysis of its expansive propensities.

Yet something must have been missing from Smith's conception. For although he saw an evolution for society, he did

not see a revolution -- the Industrial Revolution. Smith did not see in the ugly factory system, in the newly tried

corporate form of business organization, or in the weak attempts of journeymen to form protective organizations, the

first appearance of new and disruptively powerful social forces. In a sense his system presupposes that 18th-century

England will remain unchanged

forever. Only in quantity will it grow: more people, more goods, more wealth; its quality will remain unchanged. His

are the dynamics of a static community; it grows but it never matures. But, although the system of evolution has been

vastly amended, the great panorama of the market remains as a major achievement.

For Smith's encyclopedic scope and knowledge there can be only admiration. The Wealth of Nations and The Theory of

Moral Sentiments, together with his few other essays, reveal that Smith was much more than just an economist. He was

a philosopher-psychologist-historian-sociologist who conceived a vision that included human motives and historic

"stages" and economic mechanisms, all of

which expressed the plan of the Great Architect of Nature (as Smith called him). From this viewpoint, The Wealth of

Nations is more than a masterwork of political economy. It is part of a huge conception of the human adventure itself.

Karl Marx and Fredrich Engels - Manifesto of the Communist Party

A spectre is haunting Europe -- the spectre of communism. All the powers of old Europe have entered into a holy

alliance to exorcise this spectre: Pope and Tsar, Metternich and Guizot, French Radicals and German police-spies.

Where is the party in opposition that has not been decried as communistic by its opponents in power? Where is the

opposition that has not hurled back the branding reproach of communism, against the more advanced opposition parties,

as well as against its reactionary adversaries?

Two things result from this fact:

I. Communism is already acknowledged by all European powers to be itself a power.

II. It is high time that Communists should openly, in the face of the whole world, publish their views, their aims, their

tendencies, and meet this nursery tale of the spectre of communism with a manifesto of the party itself.

To this end, Communists of various nationalities have assembled in London and sketched the following manifesto, to be

published in the English, French, German, Italian, Flemish and Danish languages.

I -- BOURGEOIS AND PROLETARIANS

The history of all hitherto existing society [2] is the history of class struggles.

Freeman and slave, patrician and plebian, lord and serf, guild-master [3] and journeyman, in a word, oppressor and

oppressed, stood in constant opposition to one another, carried on an uninterrupted, now hidden, now open fight, a fight

that each time ended, either in a revolutionary reconstitution of society at large, or in the common ruin of the contending

classes.

In the earlier epochs of history, we find almost everywhere a complicated arrangement of society into various orders, a

manifold gradation of social rank. In ancient Rome we have patricians, knights, plebians, slaves; in the Middle Ages,

feudal lords, vassals, guild-masters, journeymen, apprentices, serfs; in almost all of these classes, again, subordinate

gradations.

The modern bourgeois society that has sprouted from the ruins of feudal society has not done away with class

antagonisms. It has but established new classes, new conditions of oppression, new forms of struggle in place of the old

ones.

Our epoch, the epoch of the bourgeoisie, possesses, however, this distinct feature: it has simplified class antagonisms.

Society as a whole is more and more splitting up into two great hostile camps, into two great classes directly facing each

other -- bourgeoisie and proletariat. From the serfs of the Middle Ages sprang the chartered burghers of the earliest

towns. From these burgesses the first elements of the bourgeoisie were developed.

The discovery of America, the rounding of the Cape, opened up fresh ground for the rising bourgeoisie. The East-Indian

and Chinese markets, the colonisation of America, trade with the colonies, the increase in the means of exchange and in

commodities generally, gave to commerce, to navigation, to industry, an impulse never before known, and thereby, to

the revolutionary element in the tottering feudal society, a rapid development.

The feudal system of industry, in which industrial production was monopolized by closed guilds, now no longer suffices

for the growing wants of the new markets. The manufacturing system took its place. The guild-masters were pushed

aside by the manufacturing middle class; division of labor between the different corporate guilds vanished in the face of

division of labor in each single workshop.

Meantime, the markets kept ever growing, the demand ever rising. Even manufacturers no longer sufficed. Thereupon,

steam and machinery revolutionized industrial production. The place of manufacture was taken by the giant, MODERN

INDUSTRY; the place of the industrial middle class by industrial millionaires, the leaders of the whole industrial

armies, the modern bourgeois.

Modern industry has established the world market, for which the discovery of America paved the way. This market has

given an immense development to commerce, to navigation, to communication by land. This development has, in turn,

reacted on the extension of industry; and in proportion as industry, commerce, navigation, railways extended, in the

same proportion the bourgeoisie developed, increased its capital, and pushed into the background every class handed

down from the Middle Ages.

We see, therefore, how the modern bourgeoisie is itself the product of a long course of development, of a series of

revolutions in the modes of production and of exchange.

Each step in the development of the bourgeoisie was accompanied by a corresponding political advance in that class.

An oppressed class under the sway of the feudal nobility, an armed and self-governing association of medieval

commune [4]: here independent urban republic (as in Italy and Germany); there taxable "third estate" of the monarchy

(as in France); afterward, in the period of manufacturing proper, serving either the semi-feudal or the absolute monarchy

as a counterpoise against the nobility, and, in fact, cornerstone of the great monarchies in general -- the bourgeoisie has

at last, since the establishment of Modern Industry and of the world market, conquered for itself, in the modern

representative state, exclusive political sway. The executive of the modern state is but a committee for managing the

common affairs of the whole bourgeoisie.

The bourgeoisie, historically, has played a most revolutionary part.

The bourgeoisie, wherever it has got the upper hand, has put an end to all feudal, patriarchal, idyllic relations. It has

pitilessly torn asunder the motley feudal ties that bound man to his "natural superiors", and has left no other nexus

between people than naked self-interest, than callous "cash payment". It has drowned out the most heavenly ecstacies of

religious fervor, of chivalrous enthusiasm, of philistine sentimentalism, in the icy water of egotistical calculation. It has

resolved personal worth into exchange value, and in place of the numberless indefeasible chartered freedoms, has set up

that single, unconscionable freedom -- Free Trade. In one word, for exploitation, veiled by religious and political

illusions, it has substituted naked, shameless, direct, brutal exploitation.

The bourgeoisie has stripped of its halo every occupation hitherto honored and looked up to with reverent awe. It has

converted the physician, the lawyer, the priest, the poet, the man of science, into its paid wage laborers.

The bourgeoisie has torn away from the family its sentimental veil, and has reduced the family

relation into a mere money relation.

The bourgeoisie has disclosed how it came to pass that the brutal display of vigor in the Middle Ages, which

reactionaries so much admire, found its fitting complement in the most slothful indolence. It has been the first to show

what man's activity can bring about. It has accomplished wonders far surpassing Egyptian pyramids, Roman aqueducts,

and Gothic cathedrals; it has conducted expeditions that put in the shade all former exoduses of nations and crusades.

The bourgeoisie cannot exist without constantly revolutionizing the instruments of production, and thereby the relations

of production, and with them the whole relations of society. Conservation of the old modes of production in unaltered

form, was, on the contrary, the first condition of existence for all earlier industrial classes. Constant revolutionizing of

production, uninterrupted disturbance of all social conditions, everlasting uncertainty and agitation distinguish the

bourgeois epoch from all earlier ones. All fixed, fast frozen relations, with their train of ancient and venerable

prejudices and opinions, are swept away, all new-formed ones become antiquated before they can ossify. All that is

solid melts into air, all that is holy is profaned, and man is at last compelled to face with sober senses his real condition

of life and his relations with his kind.

The need of a constantly expanding market for its products chases the bourgeoisie over the entire surface of the globe. It

must nestle everywhere, settle everywhere, establish connections everywhere.

The bourgeoisie has, through its exploitation of the world market, given a cosmopolitan character to production and

consumption in every country. To the great chagrin of reactionaries, it has drawn from under the feet of industry the

national ground on which it stood. All old established national industries have been destroyed or are daily being

destroyed. They are dislodged by new industries, whose introduction becomes a life and death question for all civilized

nations, by industries that no longer work up indigenous raw material, but raw material drawn from the remotest zones;

industries whose products are consumed, not only at home, but in every quarter of the globe. In place of the old wants,

satisfied by the production of the country, we find new wants, requiring for their satisfaction the products of distant

lands and climes. In place of the old local and national seclusion and self-sufficiency, we have intercourse in every

direction, universal inter-dependence of nations. And as in material, so also in intellectual

production. The intellectual creations of individual nations become common property. National

one-sidedness and narrow-mindedness become more and more impossible, and from the numerous national and local

literatures, there arises a world literature.

The bourgeoisie, by the rapid improvement of all instruments of production, by the immensely facilitated means of

communication, draws all, even the most barbarian, nations into civilization. The cheap prices of commodities are the

heavy artillery with which it forces the barbarians' intensely obstinate hatred of foreigners to capitulate. It compels all

nations, on pain of extinction, to adopt the bourgeois mode of production; it compels them to introduce what it calls

civilization into their midst, i.e., to become bourgeois themselves. In one word, it creates a world after its own image.

The bourgeoisie has subjected the country to the rule of the towns. It has created enormous cities, has greatly increased

the urban population as compared with the rural, and has thus rescued a considerable part of the population from the

idiocy of rural life. Just as it has made the country dependent on the towns, so it has made barbarian and semi-barbarian

countries dependent on the civilized ones, nations of peasants on nations of bourgeois, the East on the West.

The bourgeoisie keeps more and more doing away with the scattered state of the population, of the means of production,

and of property. It has agglomerated population, centralized the means of production, and has concentrated property in a

few hands. The necessary consequence of this was political centralization. Independent, or but loosely connected

provinces, with separate interests, laws, governments, and systems of taxation, became lumped together into one nation,

with one government, one code of laws, one national class interest, one frontier, and one customs tariff.

The bourgeoisie, during its rule of scarce one hundred years, has created more massive and more colossal productive

forces than have all preceding generations together. Subjection of nature's forces to man, machinery, application of

chemistry to industry and agriculture, steam navigation, railways, electric telegraphs, clearing of whole continents for

cultivation, canalization or rivers, whole populations conjured out of the ground -- what earlier century had even a

presentiment that such productive forces slumbered in the lap of social labor?

We see then: the means of production and of exchange, on whose foundation the bourgeoisie built itself up, were

generated in feudal society. At a certain stage in the development of these means of production and of exchange, the

conditions under which feudal society produced and exchanged, the feudal organization of agriculture and

manufacturing industry, in one word, the feudal relations of property became no longer compatible with the already

developed productive forces; they became so many fetters. They had to be burst asunder; they were burst asunder.

Into their place stepped free competition, accompanied by a social and political constitution adapted in it, and the

economic and political sway of the bourgeois class.

A similar movement is going on before our own eyes. Modern bourgeois society, with its relations of production, of

exchange and of property, a society that has conjured up such gigantic means of production and of exchange, is like the

sorcerer who is no longer able to control the powers of the nether world whom he has called up by his spells. For many

a decade past, the history of industry and commerce is but the history of the revolt of modern productive forces against

modern conditions of production, against the property relations that are the conditions for the existence of the bourgeois

and of its rule. It is enough to mention the commercial crises that, by their periodical return, put the existence of the

entire bourgeois society on its trial, each time more threateningly. In these crises, a great part not only of the existing

products, but also of the previously created productive forces, are periodically destroyed. In these crises, there breaks

out an epidemic that, in all earlier epochs, would have seemed an absurdity -- the epidemic of overproduction. Society

suddenly finds itself put back into a state of momentary barbarism; it appears