* Your assessment is very important for improving the workof artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download New variant of rabbit haemorrhagic disease

Brucellosis wikipedia , lookup

Hospital-acquired infection wikipedia , lookup

Meningococcal disease wikipedia , lookup

Neonatal infection wikipedia , lookup

Onchocerciasis wikipedia , lookup

Oesophagostomum wikipedia , lookup

Orthohantavirus wikipedia , lookup

Chagas disease wikipedia , lookup

Eradication of infectious diseases wikipedia , lookup

Ebola virus disease wikipedia , lookup

Human cytomegalovirus wikipedia , lookup

Herpes simplex virus wikipedia , lookup

Coccidioidomycosis wikipedia , lookup

Middle East respiratory syndrome wikipedia , lookup

Leptospirosis wikipedia , lookup

African trypanosomiasis wikipedia , lookup

Schistosomiasis wikipedia , lookup

West Nile fever wikipedia , lookup

Hepatitis C wikipedia , lookup

Marburg virus disease wikipedia , lookup

Henipavirus wikipedia , lookup

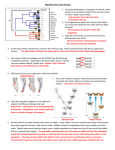

Vet Times The website for the veterinary profession https://www.vettimes.co.uk New variant of rabbit haemorrhagic disease – implications for UK pets Author : Frances Harcourt-Brown Categories : Exotics, Vets Date : February 8, 2016 Rabbit haemorrhagic disease (RHD) is a universally recognised cause of sudden death in rabbits and vaccination has proved to be an effective control. Image: iStock © Christopher Arndt However, there has been an upsurge in cases of RHD and vaccinated rabbits have been affected. A new variant of RHD is believed to be responsible. This is proving a problem in rescue centres and may be a problem in veterinary surgeries as well. History and terminology In 1984, a highly lethal disease broke out in rabbits in China. The disease was characterised by haemorrhages around the body. A calicivirus was identified as the cause. It was named viral haemorrhagic disease (VHD) or rabbit haemorrhagic disease (RHD), with the latter becoming the standard term in recent years. The acronym RHDV (rabbit haemorrhagic disease virus) is used to describe the virus. 1 / 10 Since the discovery of RHD, variants of the virus have emerged (RHDVa and RHDVb). Nonpathogenic strains of the calicivirus have also been found. The RHDVb variant has been recently shown to differ from RHDV in many characteristics, so the virus was renamed RHDV2. There is an opinion this is a new virus, which is a distinct serotype from RHD. The term “lagovirus” encompasses all types of RHDV and its variants. ‘Classic’ RHD The first outbreak of RHD in China appeared to originate from a colony of angora rabbits imported from Germany. Millions of rabbits were lost in a year. The disease was introduced to Korea by rabbit fur (Abrantes et al, 2012) and subsequently spread to other countries in Asia. In Europe, RHD was first diagnosed in Italy in 1986. By 1988, it was reported in many countries worldwide; it was probably introduced through rabbit meat. RHD spread to the wild rabbit population and, by 1990, the disease reached Scandinavia, where wild rabbits in the densely populated island of Gotland became nearly extinct in one week. Hundreds of rabbits were seen dead in the fields and many more died in their burrows. The first recorded outbreaks of RHD in wild rabbits in the UK were recorded in 1994 (White et al, 2001). In 1997, in Australia, RHD was released on to Wardang Island to biologically control the wild rabbit population. Infection spread to the mainland, where it has killed millions of wild rabbits. The infection was also surreptitiously introduced into New Zealand. The first confirmed case in the United States occurred in 2000 in a small breeding colony of exhibition rabbits in Iowa. Twenty-five of the 27 rabbits died with no indication of the source of infection (Percy and Barthold, 2007). Non-pathogenic rabbit calicivirus Although fatalities from RHD were first reported in 1984, retrospective testing showed antibodies to the virus in sera collected before that time. It was proposed non-pathogenic strains of RHDV rabbit calicivirus (RCV) could have protected rabbits by stimulating antibody production (Chasey et al, 1995). In 1996, a non-pathogenic calicivirus was recovered from breeding rabbits in Italy that produced seroconversion and was found to protect rabbits against RHD. Subsequent investigations in 2 / 10 Australia and the UK revealed the presence of non-pathogenic strains of calicivirus that may confer some immunity to RHD. Studies in Australia suggest rabbits living in areas of higher rainfall are more likely to be infected with RCV and, therefore, may have some immunity to RHD (Liu et al, 2014). New variant In 2010, an atypical outbreak of RHD occurred in a rabbitry in France in which 25% of vaccinated rabbits died (Le Gall-Reculé et al, 2013). Emergency vaccination appeared to stop the mortalities, but in 7 to 15 days compared with the usual 7 to 9 days. New outbreaks of atypical RHD in wild rabbits also occurred. Samples were genetically analysed and found the virus causing the fatalities was related to, but highly distinct from, the strains of RHD isolated from previous outbreaks. This variant is known as RHD2, and the virus as RHDV2. By 2011, this variant was identified in Italy. It was detected in the UK in 2013, although retrospective sample analysis suggests it has been present since 2010 (Westcott and Choudhury, 2015). The infection has potential to devastate the wild rabbit population and can affect vaccinated pet rabbits. Unlike RHDV, it also appears to affect hares. Natural immunity to RHDV and RHDV2 Most rabbits younger than four weeks remain unaffected by RHD and develop a lifelong immunity, if exposed to the disease. Unexposed rabbits become increasingly susceptible until 6 to 10 weeks old, when physiological resistance to the virus disappears. This age resistance is an interesting feature of the disease. It appears to be due to a rapid and effective inflammatory response by the liver, with a sustained elevation in local and systemic B macrophages and T lymphocytes (Marques et al, 2012). Subsequent exposure to the virus boosts immunity, protecting these young rabbits when they reach adulthood (Ferreira, 2006). This age immunity does not occur with RHDV2; young and suckling rabbits may be affected. Vaccination Due to the devastating effects of RHD in China, a vaccine was quickly developed from inactivated virus obtained from the liver and spleens of infected rabbits. 3 / 10 Although the immunological response to vaccines was good, they have been superseded in the UK by a bivalent vaccine that protects against both myxomatosis and RHD. It is constructed from a laboratory-attenuated strain of myxoma virus and the capsid protein gene of RHDV. The vaccine is only partially effective against RHDV2, so some vaccinated rabbits can still succumb to the disease. Vaccines against RHDV2 have been developed in France and Spain, but are not available in UK. Characteristics and transmission of RHDV RHD only affects European rabbits (Oryctolagus cuniculus). It does not affect other lagomorphs, such as cottontails, or other small mammals, such as chinchillas, guinea pigs, rats and mice. The RHD virus is a positive-sense, single-stranded RNA virus and the complete genomic sequence has been determined. However, it does not grow in tissue culture, which limits research. RHDV is difficult to kill and can survive harsh environmental conditions. It can survive temperatures of 50°C for up to an hour and is not inactivated by freezing. The virus can survive in the environment and rabbit carcases for months (Henning et al, 2005). Infection is easily transmitted between infected rabbits by the oral, nasal or conjunctival routes, with the digestive system and respiratory tract as the main portals. Only a few virions are required to produce infection. Food bowls and bedding can transmit infection. Carcases from wild rabbits that died from RHD can be a source of infection, by spreading the virus via the faeces of scavengers. It is believed rabbits that recover from RHD are potentially infectious to other rabbits for one month. It is not known how long the period is for RHDV2. Clinical signs of RHD RHD has a short incubation period of one to four days. The virus replicates in many tissues, including the lung, liver and spleen, with subsequent viraemia and haemorrhage. The RHD calicivirus has a predilection for hepatocytes and replicates in the cytoplasm of these cells. The disease it causes is essentially a necrotising hepatitis, often associated with necrosis of the spleen. Disseminated intravascular coagulation produces fibrinous thrombi in small blood vessels in most organs, notably the lungs, heart and kidneys, resulting in haemorrhages. Death is due to disseminated intravascular coagulopathy or liver failure. Three manifestations of the infection may be seen: Peracute, with animals found dead within hours of eating and behaving normally. This is a common presentation. 4 / 10 Acute, with affected rabbits showing lethargy, pyrexia (above 40°C) and increased respiratory rate. These animals usually die within 12 hours. Blood samples show leukopenia, thrombocytopenia, fibrin thrombi and markedly raised liver enzymes, but a feature of the disease is a dramatic drop in blood pressure that makes it difficult to find a vein to take blood samples or set up intravenous fluids. Dying rabbits are pallid, shocked and collapsed. Haematuria, haemorrhagic vaginal discharges or foamy exudate from the nostrils may be seen. Vascular infarcts can occur in the brain and occasionally convulsions or other neurological signs are seen just before death. The “classic” picture is a dead rabbit in opisthotonus with a haemorrhagic nasal discharge. Rarely, a rabbit may recover from the acute phase only to develop jaundice and die a few days later. A rabbit can very occasionally survive this period, but with permanent liver damage. Subacute, with rabbits showing mild or subclinical signs from which they recover and become immune to infection. Clinical signs of RHD2 Experimental infections with RHDV2 have shown mortalities occur later and over a longer period than RHD. In laboratory rabbits infected with RHDV2, clinical signs developed after three to nine days and lasted, on average, five days instead of three to four days with RHD (Le Gall-Reculé et al, 2013). Subacute or chronic infections were more frequent and more rabbits survived, showing a more protracted disease with weight loss and jaundice. Diagnosis 5 / 10 Figure 1. Gross appearance of the abdominal organs of a rabbit that died from RHD. The liver is enlarged and congested. RHD is usually diagnosed at postmortem. It is suspected in any sudden death, especially if more than one rabbit in the household has died. The postmortem picture may be of a healthy rabbit with non-impacted food in the stomach and hard faecal pellets in the distal colon, suggesting death was sudden. Gross postmortem signs may be minimal or obvious (Figure 1). Suggestive findings include: An enlarged pale, friable liver with a distinct lobular pattern (Figure 2). The liver is always affected, although the gross appearance may not reflect the severe histopathological changes. An enlarged spleen is highly suggestive of RHD (Figure 3). There are few differential diagnoses, as acute viraemic infections in rabbits are rarely encountered. Haemorrhages in any part of the body may or may not be obvious. Free blood may be found in the abdomen or in the retroperitoneal spaces (Figure 4). Ecchymotic haemorrhages may be seen on the serosal surfaces or in the lungs (Figure 5). Petechiae may be seen in the muscles, including the heart. A trachea filled with foamy exudate that may or may not be blood stained. 6 / 10 Figure 2. Appearance of the liver and lungs. Close examination shows a distinct lobular pattern. Haemorrhages can be seen in the lungs. Figure 3. An enlarged spleen is seen in acute cases of RHD. Areas of focal necrosis are seen histologically. Figure 4. Free blood may be seen in the abdomen. In this case there was a small amount of haemorrhage. 7 / 10 Figure 5. The lungs show areas of haemorrhage and congestion. Histopathology confirms acute hepatic necrosis. Apoptosis (extensive vacuolations, alterations in the mitochondrial structure, karyopyknosis and karyolysis) may be seen on electron microscopy. There may be many other changes, such as pulmonary oedema, acute nephropathy or alveolar haemorrhage. Necrosis of lymphocytes in the splenic follicles and lymph nodes are typical findings. Fibrin thrombi are present in small vessels of multiple organs, including the kidneys, brain, adrenal glands, heart, testes and lung. Erythrophagocytosis may be evident in the spleen. The typical histopathological changes in the liver are highly suggestive of RHD, but further tests are required to confirm the diagnosis and identify the variant. PCR testing is available at the APHA. Fresh or frozen liver is required. Treatment There is no specific treatment for affected rabbits. Most will die quickly. Generalised supportive care, including fluid therapy, syringe feeding and warmth, is indicated for rabbits that survive, but bear in mind these rabbits can be infectious to others; barrier nursing is required. Prevention Although vaccination is effective against RHD, there is no certain way of protecting a pet rabbit in the UK against RHDV2. Until a vaccine against RHDV2 is available, the vaccine against RHDV is the best option. It is recommended vaccines are given at least annually and earlier if the rabbit is deemed to be “at risk” through, for example, boarding kennels, hospitalisation at a practice or a show where there is 8 / 10 increased contact with other rabbits. Early vaccination (four weeks) is recommended for young rabbits, with a second vaccination four to six weeks later. The risk of spreading RHDV2 from outbreaks in wild rabbits to pet rabbits is unknown. Picking wild plants to feed pet rabbits (foraging) is growing in popularity because it has many health benefits. Wild plants could also theoretically be a source of infection, but this has not been demonstrated. The risk has to be weighed up alongside the possibility of introducing infection from other sources, such as flying insects or on footwear. Even hay could be a source of infection; urine, faeces or tissues of rabbits that were hiding in the hay before they died of RHD could contaminate it. It is also possible exposure to lagoviruses from the wild rabbit population is advantageous for a healthy, vaccinated pet rabbit; it may develop a stronger immunity if challenged. Not all lagoviruses are pathogenic, so natural exposure could be protective. The situation is not clear and more information should come to light in the future. References Abrantes J, van der Loo W, Le Pendu J and Esteves PJ (2012). Rabbit haemorrhagic disease (RHD) and rabbit haemorrhagic disease virus (RHDV): a review, Vet Res 43: 12. Chasey D, Lucas MH, Westcott DG et al (1995). Development of a diagnostic approach to the identification of rabbit haemorrhagic disease, Vet Rec 137(7): 158-160. Ferreira PG, Costa-E-Silva A and Águas AP (2006). Liver disease in young rabbits infected by calicivirus through nasal and oral routes, Res Vet Sci 81(3): 362-365. Henning J, Meers J, Davies PR and Morris RS (2005). Survival of rabbit haemorrhagic disease virus (RHDV) in the environment, Epidemiol Infect 133(4): 719-730. Le Gall-Reculé G, Lavazza A, Marchandeau S et al (2013). Emergence of a new lagovirus related to rabbit haemorrhagic disease virus, Vet Res 44: 81. Liu J, Fordham DA, Cooke BD et al (2014). Distribution and prevalence of the Australian non-pathogenic rabbit calicivirus is correlated with rainfall and temperature, PLoS One 9(12): e113976. Marques RM, Costa-E-Silva A, Águas AP et al (2012). Early inflammatory response of young rabbits attending natural resistance to calicivirus (RHDV) infection, Vet Immunol Immunopathol 150(3-4): 181-188. Percy DH and Barthold SW (2007). Rabbit. In Pathology of Laboratory Rodents and Rabbits (3rd edn), Blackwell, Iowa: 253-307. Westcott DG and Choudhury B (2015). Rabbit haemorrhagic disease virus 2-like variant in Great Britain, Vet Rec 176(3): 74. White PJ, Norman RA, Trout RC et al (2001). The emergence of rabbit haemorrhagic 9 / 10 disease virus: will a non-pathogenic strain protect the UK?, Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci 356(1,411): 1,087-1,095. 10 / 10 Powered by TCPDF (www.tcpdf.org)