* Your assessment is very important for improving the workof artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download The American Indian in the Civil War

Issues of the American Civil War wikipedia , lookup

Military history of African Americans in the American Civil War wikipedia , lookup

Battle of Wilson's Creek wikipedia , lookup

Union (American Civil War) wikipedia , lookup

Georgia in the American Civil War wikipedia , lookup

Conclusion of the American Civil War wikipedia , lookup

Mississippi in the American Civil War wikipedia , lookup

Border states (American Civil War) wikipedia , lookup

United Kingdom and the American Civil War wikipedia , lookup

Commemoration of the American Civil War on postage stamps wikipedia , lookup

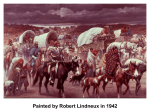

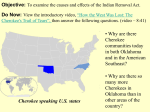

Shared Stories of the Civil War Reader’s Theater Project The Cherokee Nation in the Civil War After a protracted court battle in the early 1830s, the Cherokee Nation were eventually removed from their homelands in Georgia and relocated to Indian Territory, in modern-day southeastern Kansas and northeastern Oklahoma. When the Kansas Territory opened for settlement in 1854, the Cherokee once again faced displacement. The tribe approached the federal government for assistance. Although the Cherokee had agreements with the government providing support and protection for their lands, their requests for help went unanswered. As the Border War raged between Kansas and Missouri, and tensions mounted between the North and the South, war seemed inevitable. The Cherokee faced a decision: In the event of Civil War, would they side with the United States government or the Confederacy? Please Note: Regional historians have reviewed the source materials used, the script, and the list of citations for accuracy. The Cherokee Nation in the Civil War is part of the Shared Stories of the Civil War Reader’s Theater project, a partnership between the Freedom’s Frontier National Heritage Area and the Kansas Humanities Council. FFNHA is a partnership of 41 counties in eastern Kansas and western Missouri dedicated to connecting the stories of settlement, the Border War and the The Cherokee Nation in the Civil War 2 Enduring Struggle for Freedom in this area. KHC is a non-profit organization promoting understanding of the history and ideas that shape our lives and strengthen our sense of community. For More Information: Freedom’s Frontier National Heritage Area www.freedomsfrontier.org Kansas Humanities Council www.kansashumanities.org Shared Stories of the Civil War Reader’s Theater project A partnership between Freedom’s Frontier National Heritage Area and the Kansas Humanities Council Version 3/28/11 The Cherokee Nation in the Civil War 3 Introduction Instructions: The facilitator can either read the entire introduction out loud or summarize key points. This introduction is intended to provide context to the reader’s theater script, it is not a comprehensive look in the role played by all American Indians in the Civil War or the complete history of the Cherokee Nation. The early relationship in the United States between the indigenous populations and the Europeans settlers was, in some ways, a holdover from the established Doctrine of Discovery, which gave Europeans dominion over the indigenous populations of any lands they conquered. This perspective was solidified in 1823 with the United States Supreme Court decision in Johnson v. McIntosh. Johnson and McIntosh both claimed ownership of the same track of land in Illinois. Johnson purchased the land from the Piankeshaw Indians, while McIntosh purchased the same land from the United States government. The Supreme Court found in favor of McIntosh, stating that only the United States government had the right to purchase and sell the lands occupied by indigenous people. In writing the opinion, Chief Justice John Marshall described Indians as occupants of the land, not owners. Indigenous populations struggled to establish themselves as sovereign nations in the eyes of the United States government, with freedom to enforce their own laws and to retain their homelands. The United States government failed to acknowledge their sovereignty and began forcibly removing indigenous populations from their homelands in the East to land in the West. The Cherokee Nation was one of many that experienced removal at the hands of the United States government. After a protracted court battle in the early 1830s, they were eventually removed from their homelands in Georgia and relocated to Indian Territory, in modern-day southeastern Kansas and northeastern Oklahoma. When the Kansas Territory opened for settlement in 1854,the Cherokee once again faced displacement. The tribe approached the federal government for assistance. Although the Shared Stories of the Civil War Reader’s Theater project A partnership between Freedom’s Frontier National Heritage Area and the Kansas Humanities Council Version 3/28/11 The Cherokee Nation in the Civil War 4 Cherokee had agreements with the government providing support and protection for their lands, their requests for help went unanswered. As the Border War raged between Kansas and Missouri, and tensions mounted between the North and the South, war seemed inevitable. The Cherokee faced a decision: In the event of Civil War, would they side with the United States government or the Confederacy? In October 1861, persuaded by promises to protect their lands and preserve their way of life, the Cherokee Nation signed an agreement with the Confederacy and assembled troops to fight within Indian Territory against the Union Army. Stand Watie and John Drew led the Confederate Cherokee troops. After defeat at the Battle of Pea Ridge in northwest Arkansas in March of 1862, Drew’s forces joined the Union and became part of the Indian Home Guard in Kansas. Stand Watie and his supporters remained with the Confederacy. Six months later, John Drew and his Indian Home Guard met Stand Watie and his Confederate forces at the First Battle of Newtonia in southwestern Missouri. For the first time in the Civil War, Cherokee troops faced one another on opposites side of the battlefield. Group Discussion Questions Instructions: The facilitator should pose one or more of these questions in advance of the reading of the script. At the conclusion of the reading, participants will return to the questions for consideration. 1. Would it have been possible for anyone living in the United States to remain neutral during the Civil War? 2. The circumstances of the Cherokee Nation were unique compared to other settlers living along the border. What motivations ultimately persuaded them to get involved? 3. How did the Doctrine of Discovery and the decisions of the U.S. Supreme Court impact the Cherokee? Did they contribute to the irreparable divisions within the tribe? Shared Stories of the Civil War Reader’s Theater project A partnership between Freedom’s Frontier National Heritage Area and the Kansas Humanities Council Version 3/28/11 The Cherokee Nation in the Civil War Shared Stories of the Civil War Reader’s Theater project A partnership between Freedom’s Frontier National Heritage Area and the Kansas Humanities Council Version 3/28/11 5 The Cherokee Nation in the Civil War 6 Script Instructions: Each part will be read out loud by an assigned reader. Readers should stand and speak into a microphone when it’s their turn. The source of the quote should also be read out loud (this is the information bolded beneath each quote). NARRATOR: The United States government used the Doctrine of Discovery as justification for claiming the homelands of American Indian tribes and forcing them to relocate to lands in the Trans-Mississippi West. No tribe was exempt, not even the Cherokee, who had successfully adopted European ideas and customs, including a written language, a constitution, formal education, and slavery. Yet, despite the Cherokee’s efforts to assimilate into the white world, the demand for their lands and riches was too great. READER 1: The Doctrine provided,…, that newly arrived Europeans immediately and automatically acquired property rights in native lands and gained governmental, political, and commercial rights over the inhabitants without the knowledge nor the consent of the indigenous peoples. Robert J. Miller, Native America, Discovered and Conquered: Thomas Jefferson, Lewis and Clark, and Manifest Destiny, 2006.i READER 2: ---they spread before the eyes of the Indians firearms, woolen garments, kegs of brandy, glass necklaces, bracelets of tinsel, earrings, and lookingglasses. If, when they have beheld all these riches, they still hesitate, it is insinuated that they have not the means of refusing their required consent and that the government itself will not long have the power of protecting them in their rights. What are they to do? Half convinced and half compelled, they go to inhabit new deserts, where the importunate whites will not let them remain ten years in tranquility. In this manner do Shared Stories of the Civil War Reader’s Theater project A partnership between Freedom’s Frontier National Heritage Area and the Kansas Humanities Council Version 3/28/11 The Cherokee Nation in the Civil War 7 the American obtain, at a very low price, whole provinces, which the richest sovereigns of Europe could not purchase. Alexis de Tocqueville, Democracy in America, 1839.ii NARRATOR: When the United States government ordered the removal of the Cherokee from their homelands in Georgia, the tribe challenged the order through the courts. The lengthy battle that followed divided the Cherokee Nation into two factions. The Treaty Party wanted to save the Cherokee and accepted removal to Indian Territory. Chief John Ross led the majority faction that opposed removal to Indian Territory. READER 3: Offering larger and larger inducements to remove with only minimal results, the federal government despaired of reaching a treaty with the duly elected representatives of the Cherokee Nation. Unable to convince the legitimate Cherokee government to give up their land, U.S. officials sought to recognize a minority faction as the new leadership with the intent of imposing any treaty they signed on the entire population. The Treaty Party, as it became known was led by Major Ridge, his son John Ridge, and nephews, Elias Boudinot,…and Stand Watie. Duane King, The Cherokee Trail of Tears, 2007.iii READER 4: I know I take my life in my hand, as our fathers have done also. We will make and sign this treaty….We can die, but the great Cherokee Nation will be saved. They will not be annihilated; they can live. Elias Bouinot at Treaty of New Echota, 1835. iv NARRATOR: Despite the legitimate leadership’s efforts to have the Treaty of New Echota declared invalid, the deed was done. The Cherokee were removed Shared Stories of the Civil War Reader’s Theater project A partnership between Freedom’s Frontier National Heritage Area and the Kansas Humanities Council Version 3/28/11 The Cherokee Nation in the Civil War 8 to Indian Territory. Many in the Cherokee Nation viewed members of the Treaty Party as traitors. READER 5: The removal of the Cherokee Indians from their life long homes in the year 1838 found me a young man in the prime of life and a private soldier in the American Army…..I saw the helpless Cherokees arrested and dragged from their homes, and driven at the bayonet point into the stockades. And in the chill of a drizzling rain on an October morning I saw them loaded like cattle or ship into six hundred and forty-five wagons and started toward the rest. One can never forget the sadness and solemnity of that morning. Chief John Ross led in prayer and when the bugle sounded and the wagons started rolling many of the children rose to their feet and waved their little hands good-by to their mountain homes, knowing they were leaving them forever. John G. Burnett, U.S. Cavalry, written in 1890. v READER 1: The Cherokees who lost their homes in the east came west in two very distinct factions. Between 1835 and 1837, members of the Treaty Party…and other supporters of removal who voluntarily relinquished their homes and lands in the east [moved to Indian Territory.] The years of 1838-39 saw the forced mass migration of the Cherokees opposed to removal and the treaty which had caused it. Bitter hatred seethed in the hearts of families who had lost everything,… David A. Cornsilk, Cherokee Observer, 1997.vi READER 2: In Indian Territory, the Cherokee soon rebuilt a democratic form of government, churches, schools, newspapers and businesses. They rebuilt a Shared Stories of the Civil War Reader’s Theater project A partnership between Freedom’s Frontier National Heritage Area and the Kansas Humanities Council Version 3/28/11 The Cherokee Nation in the Civil War 9 progressive lifestyle from remnants of the society and the culture they were forced to leave behind. History of the Cherokee Nation. NARRATOR: vii The Cherokee living in southern Kansas benefitted from the area’s excellent farmland. READER 3: May 31st. Struck camp and marched seven miles west, which brought us to … the left bank of Spring river, where emerging from the timber for the first time we came in full view of an open rolling prairie extending north, south and west as far as the eye can see. After striking the valley of this river I noticed several Indian farms, having neatly fenced fields of oats, wheat and corn. They also plant cabbage, turnips &c. The soil in this portion of the valley is very fertile. The timber on the banks of Spring river consists chiefly of oak, cottonwood & ash with a heavy undergrowth in many places. The grass and general vegetation on the prairie west is now between 6 and 8 inches long presenting rich verdure, and luxuriance. Hugh Campbell, Journal Entry, May 31, 1857.viii NARRATOR: The opening of Kansas Territory for settlement brought new settlers. Squatters soon became a problem, and the Cherokee Nation looked to the federal government to remove them. READER 4: In 1859, the Cherokee Nation sent a sharp complaint to the U.S. government and passed a law authorizing tribal law enforcement officials to cooperate with U.S. agents in removing the intruders. The U.S. government responded by ordering the white squatters to leave,… Gary L. Cheatham ’If the Union Wins, We Won’t Have Anything Left’: The Rise and Fall of the Southern Cherokees of Kansas, 2007. ix Shared Stories of the Civil War Reader’s Theater project A partnership between Freedom’s Frontier National Heritage Area and the Kansas Humanities Council Version 3/28/11 The Cherokee Nation in the Civil War NARRATOR: 10 At the start of the Civil War, the Cherokee found themselves divided, once again, along the same lines that had separated them at the time of their forced removal from Georgia. When the Confederacy arrived to woo the Cherokee Nation, the minority proslavery faction, led by Watie, was interested in joining them. The majority abolitionist faction, led by Ross, wished to remain neutral. READER 1: Although I regret most deeply the excitement which has arisen among our white brothers, yet by us it can only be regarded as a family misunderstanding among themselves. And it behooves us to be careful, in any movement of ours, to refrain from adopting any measures liable to be misconstrued or misrepresented; and in which (at present, at least) we have no direct and proper concern. I cannot but confidently believe, however, that there is wisdom and virtue and moderation enough among the people of the United States, to bring about a peaceable and satisfactory adjustment of their differences. Chief John Ross, 1861. x NARRATOR: Brigadier General Ben McCulloch, of the Confederate Army, commanded the troops in Arkansas and Indian Territory. He sought to bring the Cherokee Nation into the Confederacy. READER 3: I take the first opportunity of assuring you of the friendship of my government, and the desire that the Cherokees and other tribes in the Territory unite their fortunes with the Confederacy. I hope that you as Chief of the Cherokees will meet me with the same feelings of friendship that actuate me in coming among you, and that I may have your hearty co-operation in our common cause against a people who are endeavoring to deprive us of our rights. Shared Stories of the Civil War Reader’s Theater project A partnership between Freedom’s Frontier National Heritage Area and the Kansas Humanities Council Version 3/28/11 The Cherokee Nation in the Civil War 11 Brigadier General Ben McCulloch, 1861. xi NARRATOR: Chief Ross resolved to remain neutral. READER 4: In regard to the pending conflict between the United States and the Confederate States, I have already signified my purpose to take no part in the same course. The determination to adopt that course was the result of consideration of law and policy and seeing no reason to doubt its propriety, I shall adhere to it in good faith and hope that the Cherokee people will not fail to follow my example….We have done nothing to bring about the conflict in which you are engaged with your own peoples and I am unwilling that my people shall become its victims. Chief John Ross, 1861. xii NARRATOR: The Confederacy’s pleas were not lost on Stand Watie, leader of the Cherokee Treaty Party. Like New Echota, the Confederacy appealed to a minority faction within the Cherokee. Watie began organizing regiments to fight for the Confederacy. However, Chief Ross remained unconvinced. Both sides came together in August 1861 to determine the will of the tribe. They adopted this resolution: READER 5: Resolved, that reposing full confidence in the authorities of the Cherokee Nation, we submit to their wisdom the management of all questions which affect our interests growing out of the exigencies of the relations between the United States and the Confederate states of America, and which may render an alliance on our part with the latter states expedient and desirable. Oklahoma Genealogy Website, The Indians in the Civil War of 1861 to 1865. xiii Shared Stories of the Civil War Reader’s Theater project A partnership between Freedom’s Frontier National Heritage Area and the Kansas Humanities Council Version 3/28/11 The Cherokee Nation in the Civil War NARRATOR: 12 On August 10, 1861, Stand Watie’s regiments fought for the Confederacy at the Battle of Wilson’s Creek in Missouri. This victory for the Southern forces, combined with mounting pressure within the tribe to align with the Confederacy and the Cherokee leadership’s growing concerns over the future of the United States, convinced Chief Ross to sign a treaty with the Confederacy. READER 2: When circumstances beyond their control compel one people to sever the ties which have long existed between them and another state or confederacy, and to contract new alliances and establish new relations for the security of their rights and liberties, it is fit that they should publicly declare the reasons by which their action is justified. Declaration by the People of the Cherokee Nation, 1861. xiv NARRATOR: Through this declaration, Chief Ross detailed the Cherokee Nation’s reasons for joining forces with the Confederacy. Ross viewed the Confederacy as a drifting log, offering the Cherokee people a chance for survival. READER 3: We are in the situation of a man standing alone upon a low, naked spot of ground, with the water rising rapidly all around him. He sees the danger but does not know what to do. If he remains where he is, his only alternative is to be swept away and perish. The tide carries by him, in its mad course, a drifting log. It, perchance, comes within reach of him. By refusing it, he is a doomed man. By seizing hold of it he has a chance for his life. He can but perish in the effort, and may be able to keep his head above water until rescued, or drift to where he can help himself. Chief John Ross, 1861. xv Shared Stories of the Civil War Reader’s Theater project A partnership between Freedom’s Frontier National Heritage Area and the Kansas Humanities Council Version 3/28/11 The Cherokee Nation in the Civil War NARRATOR: 13 The Cherokee Nation signed their treaty and joined the Confederacy with beneficial terms. READER 4: Under the agreement signed on October 7, 1861, the Confederate States of America assumed all of the treaty obligations due to the Cherokee from the government of the United States. The Confederates also guaranteed the Cherokee protection from invasion, respect for Cherokee title to their lands, payments of Indian annuities, and the recognition of the Cherokee right to maintain the institution of slavery. Laurence Hauptman, Between Two Fires, 1995. xvi NARRATOR: Although Chief Ross had signed a treaty with the Confederacy, his allegiance remained in question and old factions remained within the Cherokee. Some members sided with Stand Watie, while others aligned themselves with John Drew, who was related to Chief Ross by marriage. Watie and Drew fought together at the Battle of Pea Ridge in March 1862. READER 5: …Drew’s forces were reluctant warriors….At the three-day battle of Pea Ridge, the Union forces won a major victory despite Watie’s active Shared Stories of the Civil War Reader’s Theater project A partnership between Freedom’s Frontier National Heritage Area and the Kansas Humanities Council Version 3/28/11 The Cherokee Nation in the Civil War 14 leadership right to the end of the battle. After the defeat, Drew’s Second Indian Mounted Rifles defected to the Union side while Watie and his mounted forces made their way back toward the Cherokee Nation. Now the Cherokee schism was wider – between blue and gray as well as Indian and Indian. Laurence M. Hauptman, Between Two Fires, 1995.xvii READER 1: In March 1862,…Confederate Indians fought at the Battle of Pea Ridge, Arkansas, but…were criticized for their disorderly fighting during the Southern defeat, and some of them were accused of scalping or otherwise mutilating the enemy dead. Larry Wood, The Two Civil War Battles of Newtonia, 2010. xviii NARRATOR: It quickly became apparent that the Confederacy could not live up to the promises they made to the Cherokee. The Confederate Cherokee troops who defended the borders were inadequately supplied. Ross feared invasion by Union troops was imminent and pleaded with the Confederate leadership for help. READER 5: In June 1862 federal troops,….met little resistance as they moved south from Kansas toward Cherokee Nation. ….a message from William G. Coffin, superintendent of Indian affairs, assur[ed] the chief that the United States government would not overlook its obligations to the loyal Indian tribes. Doubtless Coffin…did not consider Ross disloyal, but rather as one Shared Stories of the Civil War Reader’s Theater project A partnership between Freedom’s Frontier National Heritage Area and the Kansas Humanities Council Version 3/28/11 The Cherokee Nation in the Civil War 15 forced into an uncomfortable position. Gary E. Moulton, John Ross Cherokee Chief, 1978. xix READER 1: As a consequence of the federal invasion of Indian Territory …, the Union forces marched on the Cherokee capital of Tahlequah and captured Ross. The Cherokee’s Principal Chief was soon paroled, spending the remainder of the war in Washington, D.C. and Philadelphia after a proclamation of Cherokee loyalty to the Union. Laurence M. Hauptman, Between Two Fires, 1995.xx NARRATOR: After Chief Ross’ departure, many of the Cherokee left Indian Territory to seek safety and resources elsewhere. READER 2: From an unidentified observer: One morning I was at Emporia, Kansas, and saw slopes down the river and the whole slopes were alive with Indians. There were some on ponies and children in blankets, looking like mummies, and there they were, this great multitude of people getting into the timber…It was an awful sight. We went out to look at them, and they had had two weeks of traveling across that country, 200 miles, and the wolves followed them. Children had died or were frozen to death, some of them frozen almost in their mothers’ arms, and as these children died they threw them to the wolves to keep the wolves back. John Ehle, Trail of Tears: The Rise and Fall of the Cherokee Nation, 1988. xxi NARRATOR: Chief Ross lobbied heavily in Washington, D.C. during his time in exile, assuring the United States government of the Cherokees Nation’s loyalty. The struggles between Union and Confederate supporters within the tribe Shared Stories of the Civil War Reader’s Theater project A partnership between Freedom’s Frontier National Heritage Area and the Kansas Humanities Council Version 3/28/11 The Cherokee Nation in the Civil War 16 continued throughout the war. Watie assumed control of the Cherokee Nation. READER 2: The Union Army had been occupying the southwestern Ozarks of Missouri since the spring of 1862. The 6th Missouri Cavalry had been present..., and …the 37th Illinois Infantry and 1st Missouri Cavalry moved in to support the 6th, as rumors of encroaching Confederate troops took root. The 6th Kansas moved in and would remain stationed at Newtonia for the duration of the War. Coming in from Kansas, as well, to support the Union effort, were its first Native American soldiers, in the Indian Home Guard. They would meet their fellow Indian tribesmen at Newtonia. Community and Conflict, Battle of Newtonia, 1862. xxii NARRATOR: Newtonia, Missouri was strategic point due to its proximity to Kansas, Indian Territory, and Arkansas. The area was rich in agricultural products, mills for processing, and lead mines for ammunition. Guerilla warfare was rampant in Newtonia, as the Southern sympathizers sought to make things difficult for the Union forces in any way they could. READER 3: At seven a.m. on September 30, the fighting began. The Union outgunned the Confederates 5 to 2, but the bluecoats were unable to silence the Rebel pieces. The Union Army came in, then the Confederate forces surged. The Union retreated, and then was met with reinforcements and returned to fight the Rebels. Just when the Confederates were lagging, their reinforcements arrived. By dark, the Rebels were chasing the Yankees out of Newtonia,… The organized Union retreat, brought on by the perception of being outmanned by the Rebels, turned into a rout, as the Yankees, dropped their arms and fled. Some were captured, some were killed, and the Rebels added to their sorry arms supply with the discard weapons. Shared Stories of the Civil War Reader’s Theater project A partnership between Freedom’s Frontier National Heritage Area and the Kansas Humanities Council Version 3/28/11 The Cherokee Nation in the Civil War 17 Community and Conflict, The First Battle of Newtonia.xxiii READER 4: Newtonia is a nice clean little town But it [don’t] take many houses hear to make a town…our men had a fight with the [Rebels] hear about 10 days ago and had to retreat [there] was [too] many of them… the Rebels took some of our men [prisoners] William Murray, October 8, 1862. xxiv READER 4: They lost heavily in horses, their own poorly shod ponies; but they themselves stood fire well. To rally them after defeat proved, however, a difficult matter. Their disciplining had yet left much to be desired. Scalping of the dead took place as on the battle-field of Pea Ridge; but, in other respects, the Indians of both armies acquitted themselves well and far better than might have been expected. Annie Heloise Abel, The American Indian as Participant in the Civil War, 1919. xxv READER 5: The dead of the enemy were scalped, I am informed by an officer who was there, in or after the engagement of September 30, at Newtonia, notwithstanding my orders prohibiting it, issued long ago. Brigadier General Albert Pike, 1862. xxvi NARRATOR: The First Battle of Newtonia was a Confederate victory, but its significance lies in the troops who participated in the battle. Not only did Union Indians and Confederate Indians face one another on the battlefield, but members of the same tribe found themselves fighting on opposite sides. Bitterness and rage, lingering from removal, followed the Cherokee on to the battlefield in Missouri. Shared Stories of the Civil War Reader’s Theater project A partnership between Freedom’s Frontier National Heritage Area and the Kansas Humanities Council Version 3/28/11 The Cherokee Nation in the Civil War READER 1: 18 Although Watie had no intention of abandoning the struggle, he had begun to realize that his cause was a markedly different one from that of the Confederacy. [In November 1863], Watie also realized that the Confederate cause was lost. Fearing reprisals if he abandoned the South and wanting to insure the continuing leadership of his family in Cherokee tribal affairs in any future peace, Watie urged his followers… to press on ‘for the preservation of the Indian country.’ Laurence M. Hauptman, Between Two Fires, 1995. xxvii NARRATOR: When the war ended in April 1865, Watie sought assurance from the United States that he, his family, and his supporters and their property would be protected from encroachment by whites and from the Indians who had fought on the Union side. In September 1865, the two Cherokee factions met with representatives of the United States to write a new treaty. READER 2: At the Fort Smith conference, the Cherokee were treated as one people, as if they had all supported the Confederacy. Since the Cherokee Nation had signed a treaty with the Confederacy, [the United States representatives] insisted that it had forfeited all rights of every kind, character, and description – annuities, lands, and protection – which had been promised and guaranteed to them by the United States. Laurence M. Hauptman, Between Two Fires, 1995.xxviii NARRATOR: At the conference, the Cherokee were required to abolish slavery and cede lands in Kansas to the United States. After the new treaty, Stand Watie removed himself from leadership in the tribe. Chief John Ross died in August, 1866, ten days before the treaty was ratified by the United States Senate. Shared Stories of the Civil War Reader’s Theater project A partnership between Freedom’s Frontier National Heritage Area and the Kansas Humanities Council Version 3/28/11 The Cherokee Nation in the Civil War 19 Instructions: The facilitator will now return to the questions found on page 3 for consideration by the group. At the conclusion of the event: The local coordinator will indicate whether the scripts need to be returned. The page titled Citations is intended to be a take-home handout for participants. The words spoken by Readers in this script are the exact words of historical participants in Kansas and Missouri, 1861-1865, taken from first-hand accounts. For ease of reading, spelling and punctuation have been modernized in the script passages. You can read these accounts as they were recorded, and more, in the following sources: Footnotes i Robert J. Miller. Native America, discovered and conquered: Thomas Jefferson, Lewis and Clark, and Manifest Destiny. Westport, CT: Praeger Publishers, 2006. pg. 1 ii Alexis de Tocqueville. Democracy in America Volume I. New York: George Adlard, 1839. p. 339. iii Duane King. The Cherokee Trail of Tears. Portland, Oregon: Graphic Arts Center Publishing Company, 2007. pg. 29. iv Elias Boudinot at Treaty of New Echota on December 22, 1835. John Ehle. Trail of Tears The Rise and Fall of the Cherokee Nation. New York: Anchor Books: 1988, pg.294. v John G. Burnett written in 1890. Ibid., pg. 393. David A. Cornsilk. Footsteps – Historical Perspective:History of the Keetoowah Cherokees. The Cherokee Observer. 1997., pg. 3 (www. cherokeeobserver.org/Keetoowah/octissue97.html) vi “A Brief History of the Cherokee Nation” Official Site of the Cherokee Nation http://www,cherokee.org/Culture/57/Page/default.aspx vii Campbell’s group were near Baxter Springs on May 31, 1857. “The Southern Kansas Boundary Survey From the Journal of Hugh Campbell, Astronomical Computer.” Edited by Martha B. Caldwell. Kansas Historical Quarterly. November 1937 (vol. 6, no. 4) p. 347 http:///www.kshs.org/p/kansas-historical-quarterly-the-southern-kansas-boundary-survey/12727 viii Gary L. Cheatham. “If the Union Wins, We Won’t Have Anything Left”: The Rise and Fall of the Southern Cherokees of Kansas. P.165. ix x Chief John Ross (Cherokee) to Governor Harris (Chickasaw) “Indians in the Civil War of 1861 to 1865” Oklahoma Genealogy Website.(URL: http://www.oklahomagenealogy.com/indianscivilwar.htm) Shared Stories of the Civil War Reader’s Theater project A partnership between Freedom’s Frontier National Heritage Area and the Kansas Humanities Council Version 3/28/11 The Cherokee Nation in the Civil War 20 xi Brigadier General Ben McCulloch to John Ross, June 12, 1861.Henry J. Lemley. Historic Letters of General Ben McCulloch and Chief John Ross in the Civil War. The Chronicles of Oklahoma. (digital.library.okstate.edu/chronicles/v040/v040p286.pdf.) pg. 286. xii Chief John Ross to Brigadier General Ben McCulloch, June 17, 1861. Henry J. Lemley. Historic Letters of General Ben McCulloch and Chief John Ross in the Civil War. The Chronicles of Oklahoma. (digital.library.okstate.edu/chronicles/v040/v040p286.pdf. p. 287. Oklahoma Genealogy Website:“Indians in the Civil War 1861 to 1865” xiii “Declaration by the People of the Cherokee Nation of the Causes Which Have Impelled Them To Unite Their Fortunes With Those of the Confederate States of America” Adopted by The Cherokee National Committee, October 28, 1861. xiv xv Chief John Ross, August 21, 1861. Gary E. Moulton. John Ross Cherokee Chief. Athens, Georgia: The University of Georgia Press, 1978. pp. 172-173. xvi Laurence M. Hauptman. Between Two Fires American Indians in the Civil War. New York: The Free Press, 1995. pg. 48. xvii Ibid. xviii Larry Wood. The Two Civil War Battles of Newtonia. Charleston: The History Press, 2010. p. 38 xix Gary E. Moulton. p. 174. xx Hauptman.p. 49. xxi Ehle. p. 388 xxii Community and Conflict Website. Battle of Newtonia 1862. (www.ozarkscivilwar.org/archives/336) p.2 xxiii Ibid. p. 3 xxiv William Murray letter to Charles Murray and his mother, October 8, 1862. Missouri Digital Heritage. (cdm.sos.mo.gov/cdm4/document.php?CISOROOT=/mack&CISOPTR=388&REC=9) xxv Annie Heloise Abel. The American Indian as Participant in the Civil War.1919 The Project Gutenberg eBook #12541, released June 6, 2004, p. 194. xxvi Report of Albert Pike, Brigadier-General, Commanding Department of Indian Territory October 24, 1862. P. 894D xxvii Hauptman. p. 52 xxviii Ibid. p. 59 Shared Stories of the Civil War Reader’s Theater project A partnership between Freedom’s Frontier National Heritage Area and the Kansas Humanities Council Version 3/28/11