* Your assessment is very important for improving the workof artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download Osteoarthritis

Survey

Document related concepts

Transcript

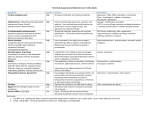

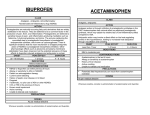

Osteoarthritis Defenition Osteoarthritis (OA) is a common, slowly progressive disorder affecting primarily the weight-bearing diarthrodial joints of the peripheral and axial skeleton. It is characterized by progressive deterioration and loss of articular cartilage, resulting in osteophyte formation, pain, limitation of motion, deformity, and progressive disability. Inflammation may or may not be present in the affected joints. Pathophysiology Primary (idiopathic) OA, the most common type, has no known cause. Subclasses of primary OA are localized OA (involving one or two sites) and generalized OA (affecting three or more sites). The term erosive OA indicates the presence of erosion and marked proliferation in the proximal and distal interphalangeal (PIP and DIP) hand joints. Secondary OA is associated with a known cause such as rheumatoid arthritis or another inflammatory arthritis, trauma, metabolic or endocrine disorders, and congenital factors. Pathophysiology OA usually begins with damage to articular cartilage through injury, excess joint loading from obesity or other reasons, or joint instability or injury that causes abnormal loading. Damage to cartilage increases the metabolic activity of chondrocytes, leading to increased synthesis of matrix constituents with cartilage swelling. This hypertrophic reparative response to damage does not restore cartilage to normal but instead is the first step in the process leading to further cartilage loss. Clinical presentation The prevalence and severity of OA increase with age. Potential risk factors include obesity, repetitive use through work or leisure activities, joint trauma, and heredity. The clinical presentation depends on duration and severity of disease and the number of joints affected. The predominant symptom is a localized deep, aching pain associated with the affected joint. Early in OA, pain accompanies joint activity and decreases with rest. With progression, pain occurs with minimal activity or at rest. Clinical presentation Joints most commonly affected are the DIP and PIP joints of the hand, the first carpometacarpal joint, knees, hips, cervical and lumbar spine, and the first metatarsophalangeal joint of the toe. In addition to pain, limitation of motion, stiffness, crepitus, and deformities may occur. Patients with lower extremity involvement may report a sense of weakness or instability. Clinical presentation Upon arising, joint stiffness typically lasts less than 30 minutes and resolves with motion. Joint enlargement is related to bony proliferation or to thickening of the synovium and joint capsule. The presence of a warm, red, and tender joint may suggest an inflammatory synovitis. Joint deformity may be present in the later stages as a resul of subluxation, collapse of subchondral bone, formation of bone cysts, or bony overgrowths. Physical examination of the affected joints reveals tenderness, crepitus, and possible joint enlargement. Heberden’s and Bouchard’s nodes are bony enlargements (osteophytes) of the DIP and PIP joints, respectively. Diagnosis The diagnosis of OA is dependent on patient history, clinical examination of the affected joint(s), radiologic findings, and laboratory testing. Criteria for the classification of OA of the hips, knees, and hands were developed by the American College of Rheumatology (ACR). The criteria include the presence of pain, bony changes on examination, a normal erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR), and radiographs showing characteristic osteophytes or joint space narrowing. • For hip OA, a patient must have hip pain and two of the following: (1) an ESR less than 20 mm/hour, (2) radiographic femoral or acetabular osteophytes, or (3) radiographic joint space narrowing. Diagnosis For knee OA, a patient must have knee pain and radiographic osteophytes in addition to one or more of the following: (1) age greater than 50 years, (2) morning stiffness of 30 minutes’ or less duration, or (3) crepitus on motion, (4) bony enlargement, (6) bony tenderness, or (7) palpable joint warmth. No specific clinical laboratory abnormalities occur in primary OA. The ESR may be slightly elevated in patients with generalized or erosive inflammatory OA. The rheumatoid factor test is negative. Analysis of the synovial fluid reveals fluid with high viscosity. This fluid demonstrates a mild leukocytosis (less than 2,000 white blood cells/mm3) with predominantly mononuclear cells. Desired outcome The major goals for the management of OA are to: (1) educate the patient, caregivers, and relatives; (2) relieve pain and stiffness; (3) maintain or improve joint mobility; (4) limit functional impairment; and (5) maintain or improve quality of life. Non-pharmacological therapy educate the patient about the extent of the disease, prognosis, and management approach. Dietary counseling and a structured weight-loss for overweight. Physical therapy—with heat or cold treatments to maintain and restore joint range of motion and reduce pain and muscle spasms. Exercise programs to strengthen muscles, improve joint function and motion, and decrease disability, pain, and the need for analgesic use. Assistive and orthotic devices such as canes, walkers, braces, heel cups, and insoles can be used during exercise or daily activities. Surgical procedures (e.g., osteotomy, partial or total arthroplasty, joint fusion) are indicated for patients with functional disability and/or severe pain unresponsive to conservative therapy. Pharmacological therapy General approch Drug therapy in OA is targeted at relief of pain. Because OA often occurs in older individuals who have other medical conditions, a conservative approach to drug treatment is warranted. An individualized approach to treatment is necessary. For mild or moderate pain, topical analgesics or acetaminophen can be used. If these measures fail or if there is inflammation, nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) may be useful. Appropriate non-drug therapies should be continued when drug therapy is initiated. Acetaminophen Acetaminophen is recommended by the ACR as first-line drug therapy for pain management of OA. The dose is 325 to 650 mg every 4 to 6 hours on a scheduled basis (maximum dose 4 g/day; maximum 2 g/day if chronic alcohol intake or underlying liver disease). However, some patients respond better to NSAIDs. Acetaminophen is usually well tolerated, but potentially fatal hepatotoxicity with overdose is well documented. It should be used with caution in patients with liver disease and those who chronically abuse alcohol. Renal toxicity occurs less frequently than with NSAIDs. NSAIDs NSAIDs at prescription strength are often prescribed for OA patients after treatment with acetaminophen proves ineffective, or for patients with inflammatory OA. Analgesic effects begin within 1 to 2 hours, whereas anti-inflammatory benefits may require 2 to 3 weeks of continuous therapy. All NSAIDs have similar efficacy in reducing pain and inflammation in OA, although individual patient response differs among NSAIDs. Selection of an NSAID depends on prescriber experience, medication cost, patient preference, toxicities, and adherence issues. An individual patient should be given a trial of one drug that is adequate in time (2 to 3 weeks) and dose. If the first NSAID fails, another agent in the same or another chemical class can be tried. Combining two NSAIDs increases adverse effects without providing additional benefit. NSAIDs Cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2) selective inhibitors (e.g., celecoxib) demonstrate analgesic benefits that are similar to traditional nonselective NSAIDs. NSAIDs NSAIDs should be avoided in late pregnancy because of the risk of premature closure of the ductus arteriosus. The most potentially serious drug interactions include the concomitant use of NSAIDs with lithium, warfarin, oral hypoglycemics, high-dose methotrexate, antihypertensives, ACEI, β-blockers, and diuretics. Topical therapy Capsaicin, an extract of red peppers that causes release and ultimately depletion of substance P from nerve fibers, has been beneficial in providing pain relief in OA when applied topically over affected joints. It may be used alone or in combination with oral analgesics or NSAIDs. To be effective, capsaicin must be used regularly, and it may take up to 2 weeks to work. It is well tolerated, but some patients experience temporary burning or stinging at the site of application. Patients should be warned not to get the cream in their eyes or mouth and to wash their hands after application. Application of the cream, gel, or lotion is recommended four times daily, but tapering to twice-daily application may enhance long-term adherence with adequate pain relief. Topical diclofenac in a dimethyl sulfoxide carrier (Pennsaid) is a safe and effective treatment for OA pain. It is thought to act primarily by local inhibition of COX-2 enzymes. Topical rubefacients containing methyl salicylate, trolamine salicylate, and other salicylates may have modest, short-term efficacy for treating acute pain associated with OA. Glucosamine & chondroitin are dietary supplements that were shown to stimulate proteoglycan synthesis from articular cartilage in vitro. Although their excellent safety profile makes them appealing for patients at high risk of adverse drug events, enthusiasm waned after results of clinical trial demonstrated no significant clinical response to glucosamine alone, chondroitin alone, or combination therapy when compared to placebo. glucosamine sulfate 1,500 mg/day and chondroitin sulfate 1,200 mg/day in divided doses. Glucosamine adverse effects are mild and include GI gas, bloating, and cramps; it should not be used in patients with shellfish allergies. The most common adverse effect of chondroitin is nausea. Corticosteriods Systemic corticosteroid therapy is not recommended in OA, given the lack of proven benefit and the well-known adverse effects with long-term use. Intraarticular corticosteroid injections can provide relief, particularly when a joint effusion is present. Average doses for injection of large joints in adults are methylprednisolone acetate 20 to 40 mg or triamcinolone hexacetonide 10 to 20 mg. After aseptic aspiration of the effusion and corticosteroid injection, initial pain relief may occur within 24 to 72 hours, with peak relief occurring in about 1 week and lasting for 4 to 8 weeks. The patient should minimize joint activity and stress on the joint for several days after the injection. Therapy is generally limited to three or four injections per year because of the potential systemic effects of the drugs and because the need for more frequent injections indicates poor response to therapy. Hyaluronate injection High-molecular-weight hyaluronic acid is a constituent of normal cartilage that provides lubrication with motion and shock absorbency during rapid movements. Hyaluronic acid injections temporarily and modestly increase synovial fluid viscosity and were reported to decrease pain, but many studies were short term and poorly controlled with high placebo response rates. 4 intraarticular hyaluronic acid preparations are available for treating pain associated with OA of the knee: sodium hyaluronate. Injections are well tolerated, but acute joint swelling and local skin reactions (e.g., rash, ecchymoses, or pruritus) have been reported. These products may be beneficial for OA of the knee that is unresponsive to other therapy, but they are expensive because treatment includes both drug and administration costs. Opioid analgesics Low-dose opioid analgesics (e.g., oxycodone) may be useful for patients who experience no relief with acetaminophen, NSAIDs, intraarticular injections, or topical therapy. They are particularly useful in patients who cannot take NSAIDs because of renal failure, or for patients in whom all other treatment options have failed and who are at high surgical risk, precluding joint arthroplasty. Low-dose opioids should be used initially, usually in combination with acetaminophen. Sustained-release compounds usually offer better pain con Tramadol Tramadol with or without acetaminophen has modest analgesic effects in patients with OA. It may also be effective as add-on therapy in patients taking concomitant NSAIDs or COX-2 selective inhibitors. As with opioids, tramadol may be helpful for patients who cannot take NSAIDs or COX-2 selective inhibitors. Tramadol should be initiated at a lower dose (100 mg/day in divided doses) and may be titrated as needed for pain control to a dose of 200 mg/day. It is available in a combination tablet with acetaminophen and as a sustained-release tablet. Opioid-like adverse effects such as nausea, vomiting, dizziness, constipation, headache, and somnolence are common. Evaluation of therapeutic outcome To monitor efficacy, the patient’s baseline pain can be assessed with a visual analog scale, and range of motion for affected joints can be assessed with flexion, extension, abduction, or adduction. Depending on the joint affected, measurement of grip strength and 50-feet walking time can help assess hand and hip/knee OA, respectively. Baseline radiographs can document the extent of joint involvement and follow disease progression with therapy. Other measures include the clinician’s global assessment based on the patient’s history of activities and limitations caused by OA, the Western Ontario and McMaster Universities Arthrosis Index, Stanford Health Assessment Questionnaire, and documentation of analgesic or NSAID use. Patients should be asked if they are having adverse effects from their medications. They should also be monitored for any signs of drug-related effects, such as skin rash, headaches, drowsiness, weight gain, or hypertension from NSAIDs. Baseline serum creatinine, hematology profiles, and serum transaminases with repeat levels at 6- to 12-month intervals are useful in identifying specific toxicities to the kidney, liver, GI tract, or bone marrow.