* Your assessment is very important for improving the workof artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download Nature’s Queer Performativity “O 25

Orchestrated objective reduction wikipedia , lookup

Quantum electrodynamics wikipedia , lookup

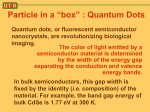

Particle in a box wikipedia , lookup

Symmetry in quantum mechanics wikipedia , lookup

Interpretations of quantum mechanics wikipedia , lookup

Wheeler's delayed choice experiment wikipedia , lookup

Quantum entanglement wikipedia , lookup

Quantum machine learning wikipedia , lookup

Quantum group wikipedia , lookup

Theoretical and experimental justification for the Schrödinger equation wikipedia , lookup

Copenhagen interpretation wikipedia , lookup

History of quantum field theory wikipedia , lookup

EPR paradox wikipedia , lookup

Quantum key distribution wikipedia , lookup

Quantum teleportation wikipedia , lookup

Hydrogen atom wikipedia , lookup

Delayed choice quantum eraser wikipedia , lookup

Quantum state wikipedia , lookup

Bohr–Einstein debates wikipedia , lookup

Wave–particle duality wikipedia , lookup

Canonical quantization wikipedia , lookup

Hidden variable theory wikipedia , lookup

Matter wave wikipedia , lookup

Atomic theory wikipedia , lookup