* Your assessment is very important for improving the workof artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download Facial Nerve Paralysis presentation (NXPowerLite)

Survey

Document related concepts

Transcript

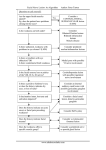

Imaging in Acute Facial Nerve Paralysis M Castillo, MD, FACR Department of Radiology University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill Overview of Presentation • Introduction • Review of facial nerve anatomy • Clinical and Imaging features of Bell’s palsy – Typical – Atypical • Other causes of acute facial paralysis Introduction • Bell’s palsy accounts for 75% of cases of acute facial nerve (7th cranial nerve) paralysis • Imaging is not needed in majority of patients unless they have atypical features • W/atypical features, MR & CT may demonstrate potentially treatable lesions affecting facial nerves • Facial nerves can be affected anywhere along their course Anatomy Review • Facial nerve nuclei lie in reticular formation of brainstem, ventral to floor (tegmentum) of 4th ventricle(4) • Motor Nuclei: – Efferent fibers surround nuclei of CN VI & form small mounds on floor of 4th ventricle (facial colliculi) • Non-Motor Nuclei: – Salivatory – Solitary Facial colliculus • Efferent fibers surround 6th CN nucleus & exit at cerebellopontine angle (CPA) • 7th nerve courses into internal auditory canal (IAC) – Within superior anterior quadrant(6) Ant Post Fallopian Canal • Exits IAC via Fallopian canal – Narrowest point throughout entire course – Felt to be culprit in facial nerve compression in Bell’s palsy & other causes of nerve swelling Geniculate ganglion • Progress to geniculate ganglion – Gives rise to greater superficial petrosal nerve • Contains taste axons from tongue & somatic fibers • Fibers then course posteriorly under lateral semicircular canal in middle ear (tympanic portion) • Fibers angle back & inferiorly at “second genu” diving the descending canal – Here last somatic & parasympathetic fibers separate from facial nerve via the chorda tympani nerve Mastoid segment Tympanic Portion • Facial nerve exits skull base at stylomastoid foramen • Facial nerve angles superiorly & anteriorly behind posterior margin of vertical mandibular ramus – Just before entering parotid gland, inferior branches originate • Posterior auricular, digastric & stylohyoid – Within substance of parotid gland, superior branches arise • Temporal, zygomatic, buccal, orbicularis oris, mandibular & cervical Clinical Signs Suggesting Site of Facial Nerve Lesion • Upper facial territory is supplied by bilateral motor cortices • Lower facial territory is supplied only by contralateral motor cortex • Therefore, unilateral central lesions spare upper face • Lesions distal to geniculate ganglion – Mostly motor abnormalities • Lesions proximal to geniculate ganglion – Motor, gustatory & autonomic abnormalities Typical Bell’s Palsy • Incidence – 15–30 per 100,000 – Usually during winter • Etiology not entirely understood – Possibly viral (Herpes Simplex Virus) or idiopathic • Viral infection of facial nerve results in demyelination, inflammation & swelling – Traps nerve in narrow confines of fallopian canal • Diagnosis of exclusion – Made only when clinical & imaging (if necessary) findings are supportive Typical Bell’s Palsy • Usually a clinical diagnosis – Acute onset unilateral (lower or upper) facial paralysis, posterior auricular pain, decreased tearing, hyperacusis (30%) & disturbances of taste – By physical examination, Bell’s palsy divided according to classification by House and Brackman • Grades 1 & 2 have better outcomes with worse outcome as grade increases. • 80-90% recover completely – Over age 60, only 40% recover completely Imaging in Typical Bell’s Palsy • Imaging in typical Bell’s palsy is not usually necessary – When necessary, MRI is best • Normal facial nerve distal to geniculate ganglion may enhance – Facial nerve proximal to geniculate ganglion does not normally enhance • In patients with Bell’s palsy, enhancement of facial nerve in fallopian & ICA is typical C/o Dr. M. Michel, Wisconsin Atypical Bell’s Palsy • Clinical features – Slower onset of symptoms – Bilateral – Recurrence • Numbness is not unusual • Progression beyond seven days suggests another cause Imaging in Atypical Bell’s Palsy C/o Dr. M. Michel, Wisconsin Alternative Causes of Acute Facial Nerve Paralysis • Atypical signs & symptoms which suggest etiology other than Bell’s palsy require imaging • Clinical history is crucial in distinguishing etiologies • Choice of imaging technique depends on clinical suspicion Lyme Disease • Lyme disease (borreliosis) – Endemic areas (Northeast USA, central Europe, Scandinavia, Canada) – Consider in children w/atypical facial palsy • Imaging: small white matter lesions similar to multiple sclerosis, enhancement of facial & other cranial nerves • Bilateral facial paralysis: 25% • Important to make diagnosis early because it is curable early w/antibiotics Ramsay Hunt Syndrome • Caused by reactivation varicella zoster virus (herpes virus type 3) • Facial paralysis + hearing loss +/- vertigo – Herpes zoster oticus • Two-thirds of patients have rash around ear • Other cranial nerves, particularly trigeminal nerves (5th CN) often involved • Worse prognosis than Bell’s (complete recovery: 50%) • Important cause of facial paralysis in children 6-15 years old C/o Dr. M. Michel, Wisconsin Infectious causes • Acute facial paralysis may result from bacterial or tuberculous infection of middle ear, mastoid & necrotizing otitis externa • Incidence of facial paralysis with otitis media: 0.16% – Infection extends via bone dehiscences to nerve in fallopian canal leading to swelling, compression & eventually vascular compromise & ischemia • Immune compromised patients are at risk for pseudomona infection • Poor prognosis (complete recovery is < 50%) Tuberculosis Parotid & peri-parotid disease HIV Infection Bezold’s abscess & coalescent mastoiditis Trauma • Most acute post traumatic facial palsies are due to t-bone fractures • Historically fractures classified as longitudinal or transverse with transverse carrying risk of permanent paralysis – Longitudinal fracture usually leads to temporary paralysis from concussion & swelling of nerve – Transverse fracture can lead to transection of nerve • In all types of paralysis due to fracture, usually the region of geniculate ganglion is involved Neoplasms • 27% of patients with tumors involving the facial nerve develop acute facial paralysis • Most common causes: schwannomas, hemangiomas (usually near geniculate ganglion) & perineural spread such as with head and neck carcinoma, lymphoma & leukemia • Other neoplasms can also involve the facial nerve – Adults: metatstatic disease, glomus tumors, vestibular schwannomas & meningiomas – Children: eosinophilic granuloma & sarcomas Hemangioma Hemangioma Facial Nerve Schwannoma Perineural Tumor Spread Glomus Tumor • Glomus tumors arising from jugular bulb (jugulare) and/or middle ear (tympanicum) may involve the facial nerve Other tumors Rhabdomyosarcoma & squamous cell carcinoma of the EAC Vestibular Schwannoma • Common tumor • However, facial nerve is resistant to compression – Therefore, tends to produce facial paralysis mostly when they attain a large size Vestibular Schwannoma Common tumor -However, facial nerve is resistant to compression, thus, tends to produce facial paralysis mostly when they attain a large size - Meningioma • Second most common primary tumor of cerebellopontine angle • Rarely results in facial paralysis Rhabdomyosarcoma Miscellaneous Causes Hypertrophic Polyneuropathy • Hypertrophic polyneuropathies occasionally lead to facial paralysis Wegener’s Granulomatosis Other Causes • Guillain-Barre Syndrome – Ascending paralysis • Iatrogenic – Temporal bone surgery • Excision of vestibular schwannoma has <10% chance of paralysis • Middle ear surgeries – Babies who required forceps delivery • >90% recovery Melkersson-Rosenthal Syndrome • Acute episodes of facial paralysis – Facial swelling – Fissured tongue • “Scrotal” tongue • Very rare • Familial but sporadic – Usually begins in adolescence • Leads to facial disfigurement • No definite therapy Conclusion • While Bell’s palsy does not typically require imaging for diagnosis, imaging evaluation is important in the work-up of patients with atypical or unusual presentations of acute facial nerve paralysis, identification of discreet lesions may lead to a change in management of these patients.