* Your assessment is very important for improving the work of artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download Morality and Practical Reason: Kant

Survey

Document related concepts

Transcript

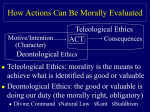

Chapter 7: Ethics Morality and Practical Reason: Kant Introducing Philosophy, 10th edition Robert C. Solomon, Kathleen Higgins, and Clancy Martin Immanuel Kant (1724-1804) • German philosopher, probably the greatest philosopher since Plato and Aristotle • Lived his entire life in a small town in East Prussia (Konigsburg); was a professor at the university there for more than thirty years • Never married; neighbors said that his habits were so regular that they could set their watches by him (a later German poet said, “It is hard to write about Kant’s life, for he had no life”) • Yet, from a safe distance, Kant was one of the most persistent defenders of the French Revolution and, in philosophy, created no less a revolution himself • His philosophical system, embodied in three huge volumes called Critique of Pure Reason (1781), Critique of Practical Reason (1788), and Critique of Judgment (1790), changed the thinking of philosophers as much as the revolution changed France • His central thesis is the defense of what he calls synthetic a priori judgments (and their moral and religious equivalents) by showing their necessity for all human experience • In this way, he escapes from Hume’s skepticism and avoids the dead-end intuitionism of his rational predecessors Kant’s Ethics: The Basics • Morality must be based solely on reason. Its central concept is the concept of duty (dein), and so morality is a matter of deontology • Morality must be autonomous, a function of individual reason, such that every rational person is capable of finding out what is right and what is wrong for himself or herself • All personal feelings, desires, impulses, and emotions are inclinations. Morality is independent of inclination The Good Will • Kant begins by saying that what is ultimately good is a good will. And a good will, in turn, is the will that exercises pure practical reason • What we will, that is, what we try to do, is wholly within our control. And reason serves the purpose of instructing our will in our duty. “The notion of duty includes that of a good will” • A good will subjects itself to rational principles. Those rational principles are moral laws, and it is action in accordance with such laws that alone makes a person good The Categorical Imperative(s) • The general formulation of Kant’s notion of duty is the categorical imperative • Categorical imperatives demand that one simply “do this” or “don’t do this,” whatever the circumstances • The word that distinguishes moral commands in general is the word ought, and categorical imperatives tell us what we ought to do, independent of circumstances or goals There is therefore but one categorical imperative, namely, this: Act only on that maxim whereby you can at the same time will that it should become a universal law • Moral or categorical imperatives provide universal laws that tell us what to do in every circumstance. With hypothetical imperatives, on the other hand, what is commanded depends upon particular circumstances • A maxim, according to Kant, is a “subjective principle of action,” or what we would call an intention. It is distinguished from an “objective principle,” that is, a universal law of reason • The categorical imperative is an a priori principle: – Necessary – Independent of particular circumstances – True for all rational beings Objections to Kant’s Conception of Morality • It may be too strict: the idea that morality and duty have nothing to do with our personal desires or inclinations seems to make the moral life undesirable • Kant’s emphasis on the categorical imperative systematically rules out all reference to particular situations and circumstances, but the right thing to do is often determined by the particular context or situation • Kant gives us no adequate way of choosing between moral imperatives that conflict. The rule that tells us “don't lie!” is categorical; so is the rule that tells us “keep your promises!” • Suppose that I promise not to tell anyone where you will be this weekend. Then some people wishing to kill you try to force me to tell. Either I break the promise, or I lie. Kant gives us no solution to this moral conflict