* Your assessment is very important for improving the workof artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download Achaemenid Persia

Athenian democracy wikipedia , lookup

Spartan army wikipedia , lookup

List of oracular statements from Delphi wikipedia , lookup

Second Persian invasion of Greece wikipedia , lookup

Battle of the Eurymedon wikipedia , lookup

Corinthian War wikipedia , lookup

Peloponnesian War wikipedia , lookup

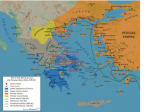

Marathon Ionian Rebellion and First Persian War Greek Cities of Asia Minor: Yauna Satrapy Ionian Rebellion (499/8-494 BCE) Possible Causes Disruption of established trade routes Egypt conquered in 525 BCE (Naucratis in decline) Darius’ Scythian expedition of 513/512 BCE and Black Sea trade Destruction of Sybaris (Italy) in 511/510 BCE (Milesian trading post) Persian rule comparatively more alien than (Hellenized) Lydian suzerainty Personal motivation? Histiaeus and Aristagoras (Herodotus, 5.35) Miletus, the Satrap, and the Naxos Expedition Tyrant of Miletus, Histiaeus, after proving his loyalty during Darius’ Scythian expedition, allowed to established post in Thrace at Myrcinus (Strymon river) Darius grows suspicious of Histiaeus’ plans at Myrcinus, recalls him to Susa (house arrest), 511-499 BCE Aristagoras (Histiaeus’ son-in-law) left to rule in Miletus Aristagoras convinces the Persian satrap, Artaphernes, to support an expedition against the island of Naxos, with designs on conquest of other islands and Euboea Aristagoras and Persian commander Megabates quarrel; Megabates warns Naxians; Naxos expedition fails (499 BCE) “Aristagoras was unable to fulfill his promise to Artaphernes; and, along with that, the expenses of the campaign that were demanded of him were causing him distress, and he was afraid because of the ill success of the army and his quarrel with Megabates, and he thought the kingship over Miletus would be taken from him. Because every one of these matters was a terror to him, he meditated revolt.” (Herodotus, 5.35) Aristagoras’ Failed Expedition against Naxos Miletus Naxos Aristagoras and Histiaeus (Herodotus, 5.35) At that same moment there came to [Aristagoras] from Susa a fellow from Histiaeus, with his head tattooed, urging Aristagoras to desert from the King. For Histiaeus wanted to urge Aristagoras to revolt but he had no other safe way of communicating with him (for all the roads were watched); so he took the most trustworthy of all his slaves and shaved his head and then tattoed a message on it and waited until the hair grew in again. He sent the man off to Miletus with no instructions save that, when he came to Miletus, he should bid Aristagoras to shave his hair off and examine his head. The tattoed marks did, as I said before, urge Aristagoras to revolt. Histiaeus acted this way because he found it dreadful to be held in Susa so long. If there were a revolt, he had great hopes that he would be sent down to the coast; but if there were no revolution in Miletus, he reckoned that he never would go home again. Electrum Coin from Lesbos Ionian Rebellion (499-494 BCE) Facing Lion’s Head 1.76 grams Western Fringe of Achaemenid Persian Empire and Athenian and Spartan Spheres of Influence Aristagoras’ Appeal to Sparta (Herodotus, 5.50) When the day appointed for the answer came and they met at the place arranged, [the Spartan king] Cleomenes asked Aristagoras how many days journey it was from the Ionian sea to where the Great King was. In everything else Aristagoras was very clever and had tricked Cleomenes successfully, but here he tripped up. He ought not to have told the truth if he wanted to bring the Spartans into Asia. However, he did tell it, saying that the journey from the sea up to Susa was a matter of three months. Cleomenes cut off all the rest of the story that Aristagoras was set to give him about the journey and said, “My friend from Miletus, away with you from Sparta before the sun sets!” Aristagoras’ Appeal to Athens (Herodotus, 5.97) It was just at this moment [when the Persians commanded the Athenians to take back Hippias], when the Athenians were thinking like this and were at odds with the Persians, that Aristagoras of Miletus came to Athens, being driven out of Sparta by King Cleomenes; for Athens was far the most powerful of the remaining cities. Aristagoras came before the popular assembly. He said all the same things that he had said in Sparta, about the riches of Asia and the Persian style of warfare and how these people were not used to spears or shields and would be easy to conquer. He said this, and he also said that Miletus was a colony of Athens and that, given the greatness of Athenian power, they should certainly protect the Milesians. He promised them anything and everything, for he was very eager indeed, and in the end he persuaded them. Ionian Revolt (499/8-494 BCE): Summary Asia Minor Greeks appeal to Sparta (unsuccessful) Asia Minor Greeks appeal to Athens (successful) Athens sends assistance (contingent of 20 ships) Burning of Sardis and Athenian Naval Support (Herodotus, 5.105) Darius and the Burning of Sardis (Herodotus, 5.105) When King Darius was informed that Sardis had been captured and burned by the Athenians and the Ionians…he first (so the story goes), when he heard the news, made no account of the Ionians--for he knew well that they would surely not get off scot-free for their rebellion--but he put the question, “Who are the Athenians?” and, having his answer, asked for a bow. He took it, fitted an arrow to it, and shot it into the sky, and as he sent it up he prayed, “Zeus, grant me the chance of punishing the Athenians.” Having said that, he ordered one of his servants that, as often as a meal was set before him, the man should says three times, “Master, remember the Athenians.” Darius’ Preparations After this, Darius tried to find out what the Greeks had in mind. Would they fight him or surrender? He sent heralds here and there throughout Greece, under instructions, and ordered them to ask for earth and water for the King. These he sent to Greece itself; others he sent to his own tributary cities that lay along the coast, and these heralds were to demand the construction of warships and horse transports. (Herodotus, 6.48) Medizing Objectives: Eretria on Euboea and Athens First Persian Expedition Battle at Marathon (September, 490 BCE) Principal Account: Herodotus, 6.108-115 Marathon: large deme of Attica 26 miles NE of Athens Modern estimations of the size of the Persian expedition around 20,000 troops Athenian and Plataean forces probably around 10,000 troops Casualties: 6,400 Persians; 192 Athenians (Herodotus, 6.117) Battle Site: Marathon (Herodotus, 6.102) So [the Persians] conquered Eretria and stayed a few days there and then sailed for Attica, pressing the Athenians hard and thinking that they would do to them the very same as they had done to the Eretrians. And because Marathon was the most suitable spot in Attica for cavalry action and the nearest to Eretria, it was to Marathon that Hippias, son of Pisistratus, guided them. Battle of Marathon (490 BCE) Battle of Marathon Double-Envelopment Tactic; Superiority of Hoplite Phalanx This was the order of battle at Marathon, and it fell out that, as the line was equal in length to the Persian formation, the middle of the Greek side was only a few ranks deep, and at this place the army was weakest; but each of the two wings was very strong. (Herodotus, 6.111) Delayed Battle: Athenians hoping for Spartan assistance (?); Athenians wait for absence of Persian cavalry (?); Athenians fight only when Persians begin moving against Athens (?) Marathon: Phases of Battle Marathon Tumulus: Monument for the Fallen Spearheads from the Battlefield of Marathon Herodotus (6.112) on Marathon The lines were drawn up, and the sacrifices were favorable; so the Athenians were permitted to charge, and they advanced on the Persians at a run. There was not less than three quarters of a mile in the no-man’s land between the two armies. The Persians, seeing them come at a run, made ready to receive them; but they believed that the Athenians were possessed by some very desperate madness, seeing their small numbers and their running to meet their enemies without the support of cavalry or archers. That was what the barbarians thought; but the Athenians, when they came to hand-to-hand fighting, fought right worthily. They were the first Greeks we know of to charge the enemy at a run and the first to face the sight of the Median dress and the men who wore it. For till then the Greeks were terrified even to hear the name of the Medes. Summary of First Persian Invasion Persian Objectives Contest for glory in Athens among great families Punitive Expedition; not Conquest Restoration of pro-Persian Pisistratid, Hippias Defeat not significant for Persian Empire (contrary to Greek representations) Miltiades of the Philaid clan (leading general in the battle) Athenians rush back to city to defend it (origins of marathon athletic event); Persians sail home Charges of Treachery against Alcmaeonids (Herodotus, 6.115) Problems with Herodotus’ Account Absence of Persian Cavalry Running of Hoplites for almost a mile Casualties (6,400 Persians; 192 Greeks) Ramifications of Marathon Ideology of Great King of Persia demands Retribution Spartan Non-Participation Spartans observed the Carneia religious festival; they had to wait for the next full moon (Herodotus, 6.106) “After the full moon there came to Athens 2,000 Spartans, who were so eager to reach the city that they arrived in Attica on the third day out of Sparta. Though they had come too late for the battle, they were nonetheless anxious to see the Persians; and so they went to Marathon and saw. Thereafter, praising the Athenians and their action, they went home again.” (Herodotus, 6.120) Athenian Reputation Soars Marathonomachoi (Aeschylus) Reinforcement of Cleisthenes’ democratic reforms Athens as Second State in Greece (to Sparta) Marathon Inscription (discovered in 2004) Good report indeed, as it reaches always the furthest ends of well-lit earth, will report the aretê of these men, how they died fighting against Medes and crowned Athens, a few having awaited the attack of many.