* Your assessment is very important for improving the workof artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download Cellulitis - National University Hospital

Survey

Document related concepts

Hepatitis C wikipedia , lookup

Clostridium difficile infection wikipedia , lookup

Hepatitis B wikipedia , lookup

Carbapenem-resistant enterobacteriaceae wikipedia , lookup

Leptospirosis wikipedia , lookup

Rocky Mountain spotted fever wikipedia , lookup

Schistosomiasis wikipedia , lookup

Anaerobic infection wikipedia , lookup

Visceral leishmaniasis wikipedia , lookup

Onchocerciasis wikipedia , lookup

Neonatal infection wikipedia , lookup

Traveler's diarrhea wikipedia , lookup

Oesophagostomum wikipedia , lookup

Staphylococcus aureus wikipedia , lookup

Transcript

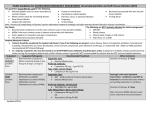

spotlight MD Singapore April 2011 Cellulitis Only Skin Deep? Cellulitis is an inflammatory condition of the skin and subcutaneous tissue. The clinical manifestations include erythema, swelling, warmth and pain. Streptococcus pyogenes and Staphylococcus aureus are the most common aetiological agents. Erysipelas may closely resemble cellulitis; however, it tends to involve only the superficial lymphatics and upper dermis and so, has a distinctive raised appearance with a clearly visible demarcation line. Clinically, it is more common in infants, children and older adults. Cellulitis involves the deeper dermis. In practice, it is often difficult to distinguish and treatment is usually the same.1 The lower limbs are the most common site for infection. Lymphangitis and regional lymph node involvement may also be seen in addition to skin erythema. Identifying the source of infection may be helpful in providing clues to the causative microorganismand to guide further management.1,2 Examples of these can be found in Table 1. Risk Factors for Acute Lower Limb Cellulitis Multiple studies have suggested that risk factors include presence Dr Surinder Pada of sites of entry, being overweight and lymphoedema.3 Dermatophytic toe web intertrigo, although in itself does not cause cellulitis, is a risk factor as it causes scaling and fissuring of the skin resulting in a portal of entry for bacteria.1-4 Diagnosis The diagnosis is generally based on the clinical setting and appearance of the lesion. Cultures of needle aspirates or punch biopsies are not indicated in routine care.1 Previous studies have shown that the microorganisms implicated remain primarily gram positive cocci. Special consideration is warranted in diabetics, which may also harbour gram negative aerobes as well anaerobes. Where bullous lesions are present, however, gram stain and culture of fluid from these lesions may be helpful. Although bacteraemia is uncommon in cellulitis, blood cultures should be drawn in patients who have superimposed lymphoedema, buccal or periorbital cellulitis, salt water or fresh water exposure, and in patients who have chills and high fevers of more than 38°C. Radiological imaging is usually unwarranted unless necrotising fasciitis or underlying acute osteomyelitis is being considered in which case an MRI would Table 1. Source of infection and possible causes of infection1,2 Source Likely bacteria Skin trauma, underlying lesion Staphylococcus aureus, group A eg, ulcer, fissured toe webs streptococcus Animal or Human bites Oral flora of biter eg, Pasteurella multocida from cat bites Oral anaerobes like Bacteroides species, Peptostreptococcus; Eikenella corrodens; viridans streptococci; Staphylococcus aureus Exposure to sea water Vibrio vulnificus Fresh water Aeromonas hydrophilia 15 16 spotlight MD Singapore April 2011 Table 2. Differential diagnosis for cellulitis1,2 Process Clinical clues Infectious Necrotizing fasciitis Acute rapidly developing, deep fascia: marked pain, tenderness and swelling. May have bullae and crepitus of overlying skin. If caused by group A streptococci, may be accompanied by toxic shock syndrome. Anaerobic myonecrosis Rapidly progressive and toxemic infection from injured muscle. Marked oedema, crepitus and brown bullae. Gram stain shows gram positive bacilli. Gas gangrene commonly from Clostridium perfringens Furuncles and carbuncles Infection of hair follicles, usually with Staphylococcus aureus. Local erythematous pustular appearing lesions. Coalescing furuncles form carbuncles Non infectious Insect and spider bite Local pruritis, no fever or toxicity Acute gout Foot involvement, joint pain, history of previous attacks Deep venous thrombophlebitis Leg involvement, sentinel venous cord and linear extension Fixed drug reaction Not as rapidly spreading as cellulitis, low fever, history of medication use Pyoderma gangrenosa Lesions become nodular or bullous and ulcerate. History of collagen vascular disease or inflammatory bowel disease Sweet’s syndrome (acute febrile neutrophilic dematosis) Acute, tender pseudovesiculated plaques, fever and neutrophilic leukocytosis. Associated with haematologic malignancy. Kawasaki’s disease Fever, conjunctivitis, acute cervical lymphadenopathy, oropharyngeal erythema, dermatitis of palms and soles, mainly in young. Neoplastic process eg, carcinoma erysipeloides, Marjolins ulcer Absence of fever, slower progression than cellulitis. the imaging of choice. In cases where gas gangrene or chronic osteomyelitis is suspected, plain x-rays may show gas pockets in tissue or cortical luscencies in bone respectively. Differential Diagnosis There are a number of important differential diagnoses for cellulitis to consider. They can be divided into infectious and non-infectious. These are summarised in Table 2. Treatment Strategies Ancillary measures Local measures to reduce swelling such as elevation and immobilisation of the affected limb can be useful. Non-stick dressings should be used on any lesions that are actively purulent. If interdigital dermatophytic infections are detected, then topical antifungal agents should be used. Patients who suffer from peripheral oedema, who are at risk of recurrent cellulitis, should observe good skin hygiene and use support stockings. Tinea paedis should be promptly treated. In some instances, expert referral to lymphoedema clinics may be beneficial. Antibiotic therapy Most studies of cellulitis have involved patients with serious infections. Studies to determine the specific criteria for case definitions of mild cellulitis are lacking. In spotlight MD Singapore April 2011 general however, for mild early cellulitis, therapy that will cover Staphylococcus aureus and Streptococcus pyogenes such as cloxacillin may be used. For patients hypersensitive to penicillin, cephalexin is a reasonable alternative. In patients who have immediate penicillin hypersensitivity, clindamycin may be considered. The duration of therapy is usually seven to ten days.1,2 We do not routinely recommend broader spectrum antibiotics such as Augmentin or the quinolones. For furunculosis, consider culture and treatment with co-trimoxazole, particularly in patients from the US, as there have been recent cases of community acquired methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) in Singapore. Who To Admit to Hospital Patients who have significant systemic features of high fever, chills, rigors and tachycardia hypotension should be referred to Accident and Emergency for consideration of admission for intravenous antibiotic therapy. Patients who have failed to respond to oral therapy after 48 hours, or have rapid spread of cellulitis with increasing pain should also be referred immediately. Failure of Treatment: What to Consider There are several things to consider if cellulitis fails to improve or resolve. The first is that patients may have deeper infections such as myositis or even osteomyelitis which typically not only need intravenous therapy but also a longer duration of antibiotics. Further imaging may be useful in this instance. Underlying conditions such as chronic venous Patients who have significant systemic features of high fever, chills, rigors, tachycardia hypotension should be referred to Accident and Emergency for consideration of admission for intravenous antibiotic therapy. Patients who have failed to respond to oral therapy after 48 hours, or, have rapid spread of cellulitis with increasing pain, should also be referred immediately. insufficiency or lymphoedema may also predispose to failure of conventional treatment due to poor drainage of infected tissue and may require a longer duration of antibiotics. The microorganisms involved may not be susceptible to the antibiotics used. Diabetics are more vulnerable to anaerobes and gram negative rods (including Burkholderia pseudomallei) as a cause cellulitis. Communityacquired methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus is also an increasing problem globally and has a predilection for causing skin and soft tissue infection.2 Noninfectious causes may also result in treatment failure. Skin biopsy, not only for gram stain and culture but histology as well, may be helpful in this scenario. Conclusion Cellulitis is a common condition seen in the community that is readily amenable to treatment. Ancillary measures as well as antibiotic therapy play an important part in its management. Failure of treatment or complete resolution should prompt further investigation. References 1Swartz MN. Cellulitis. N Engl J Med 2004;350:902-12. 2Stevens DL, Bisno AL, Chambers HF, Everett ED, Dellinger P, Goldstein EJC et al. Practice Guidelines for the Diagnosis and Management of Skin and Soft-Tissue Infections. Clin Infect Dis 2005;41:1373-406. 3Bjornsdottir S, Gottfredsson M, Thorisdottir AS, Gunnarsson GB, Rikardsdottir H, Kristjansson M et al. Risk Factors for Acute Cellulitis of the Lower Limb: A Prospective Case-Control Study. Clin Infect Dis 2005;41:1416-22. 4McNamara DR, Tleyjeh IM, Berbari EF, Lahr BD, Martinez J, Mirzoyev SA et al. A predictive Model of Recurrent Lower Extremity Cellulitis in a Population-Based Cohort. Arch Intern Med 2007;167:709-715. Dr Surinder Pada is an Associate Consultant in the Division of Infectious Disease at the National University Hospital. She is also the Chairperson of Infection Control at Alexandra Hospital. Dr Pada graduated from the University of New South Wales (Sydney) in 2000 and obtained her Fellowship of the Royal Australasian College of Physicians (FRACP) in 2009. Her areas of interest include infection control, in particular methicillin-resistant Staphyloccus aureus, as well as Influenza and general Infectious Diseases. 17