* Your assessment is very important for improving the work of artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download 296

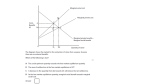

Survey

Document related concepts

Transcript

Second Pan-European Conference Standing Group on EU Politics Bologna, 24-26 June 2004 296 Industrial Subsidies in OECD Countries, 1989-1995 Presented by Umut Aydin Please note that there may be more paper authors than paper presenters http://www.jhubc.it/ecpr-bologna Industrial Subsidies in OECD Countries, 1989-1995 Umut Aydin University of Washington Prepared for 2nd Pan-European Conference on EU Politics 24-26 June, 2004, Bologna, Italy Abstract Subsidies have become increasingly important tools of industrial policy due to the gradual liberalization of trade and finance since the 1960s. Still, there is considerable variation in subsidy levels in industrialized countries. In this paper, I seek to explain the variation in the levels of industrial subsidies among OECD countries in the period 1989-1995. I test the impact of both domestic political and economic factors and international constraints on the level of subsidies. The results indicate that higher unemployment leads to higher levels of subsidies, while increased exposure to international trade and EU membership is associated with lower levels of subsidies. Contrary to theoretical expectations, leftist governments and upcoming elections are associated with lower levels of subsidies. 1. INTRODUCTION The French government recently offered euro600 million aid to rescue Alstom, the French company that makes high-speed trains and employs 110,000 workers (Economist, 2003). The amount might be exceptionally high, but the practice of granting subsidies is not exceptional. While tariffs gradually declined since the 1960s, industrial subsidies have become increasingly important (Ford and Suyker 1990, 2). Yet, the extent of government subsidization of industry varies from country to country. In 1992, the level of subsidies accounted for less than 0.5% of manufacturing GDP in Switzerland, 2.5% in Denmark and 5% in Norway.1 What accounts for this variation in the level of subsidies in these industrialized countries? This paper explains the variation in levels of state support to industry in industrialized countries. The focus is on subsidies to the manufacturing sector in sixteen Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) countries from 1989-1995. During the period under study, there was an overall upward trend in state subsidies to manufacturing in OECD countries, but with considerable diversity among individual countries and over the years (OECD 1998, 26). In this paper, I investigate the factors that influence governments’ decisions regarding the level of subsidies. In particular, this paper examines the impact of electoral pressures, governing party ideologies, unemployment, exposure to international trade and international regimes on the level of subsidies in a country. Industrial subsidies refer to “all types of selective financial government support to manufacturing industry at the central or sub-central level or, indirectly through intermediary institutions” following the definition of the OECD (OECD 1998, 19).2 1 These are the level of state support to manufacturing industry as percentage of manufacturing GDP for the year 1992 (OECD 1998). 2 This definition covers grants, low-interest loans and tax breaks to firms, but does not cover “in-kind subsidies” such as provision of real estate, goods and services at below market prices (OECD 1998, 19). 2 As tariff and non-tariff barriers to trade have declined since the 1960s, many observers argued that governments would increasingly turn to subsidies (Ford and Suyker 1990, European Commission 1989). In this view, we would expect an across the board increase in the use of subsidies as countries liberalize trade. However, arguments from the literature on globalization suggest that government’s capacity and willingness to intervene in the economy decreases at the same time that societal demands for protection increases (Cerny 1995). In the case of subsidies, I expect governments to be responding to a complex set of demands and pressures from domestic and international sources. This paper tries to capture this complexity by exploring the variation in the level of subsidies among industrial countries. This paper contributes both to theoretical and policy discussions on subsidies. Subsidies raise a fundamental question about the role of the state in the economy. Through subsidies, states influence the structure of the industry, the level of production, the price of the output and the income of the firms (Blais et al. 1986). The factors that influence the level of subsidies, the central focus of this paper, give insights into why and to what extent governments choose to intervene in the economy. More broadly, this paper also contributes to the discussions on globalization and national autonomy. Governments can use subsidies to deal with the risks created by increased international integration. Explaining the domestic and international factors that affect the level of subsidies may provide some insights into the debate about globalization and its domestic consequences. This paper is also relevant for policy discussions on subsidies. The regulation of subsidies has been an issue of debate in international trade agreements like the Uruguay Round and the negotiations for the US-Canada Free Trade Agreement (Morici 1996). Regulation of subsidies has been on the agenda of European Community since the Treaty of Rome in 1957. Recently, 3 disputes over agricultural subsidies contributed to the breakdown of the World Trade Organization talks in Cancun in September 2003. Given the significance of subsidies for international trade negotiations, this paper can make a timely contribution by exploring the reasons why governments give subsidies. The paper is organized as follows. In section two, I start with a brief summary of the existing research on subsidies and then present a set of testable hypotheses to explain the variation in subsidies in the countries and period under study. Section three discusses the research design, data sources and operationalization of the dependent and independent variables. In section four I present the results of this study and in section five, I summarize my conclusions, look at recent developments in subsidies and suggest further avenues for research. 2. SUBSIDIES IN A COMPARATIVE PERSPECTIVE In this section, I first offer a brief review of the two strands of literature that this paper draws on and contributes to. I summarize the literature on regional development policies in the US and comparative research on subsidies in industrialized countries, I then derive a set of testable hypotheses to explain the variation in the level of manufacturing subsidies in OECD economies. There is extensive discussion of subsidies and tax breaks in the literature on economic development policies of the American states. Economic development policy “refers to those efforts by government to encourage new business investment in particular locales in the hopes of directly creating or retaining jobs, setting into motion the secondary employment multiplier, and enhancing and diversifying the tax base” (Eisinger 1992, 3-4). Research on economic development policies in the United States focuses mostly on the effectiveness of state subsidies, whether they bring higher investment in states that offer them, whether they cause economic 4 distortions and more broadly whether they are harmful or useful for state economies (Saiz 2001, Burnier 1992). The increasing interest in the role of American state and local governments in economic development is reflected “in the emergence of new journals like Economic Development Quarterly, which are devoted exclusively to considering regional, state and local economic development strategies” (Grant II, Wallace and Pitney 1995: 134). Works in this literature suggest that public officials offer subsidies “to protect the state from losing business to other states, shield businesses from competition, rescue failing firms, attract outside firms or start up new businesses” (Buss 2001: 91). Most of these studies emphasize the political incentives for policymakers to offer subsidies. For elected officials, “political payoffs [of subsidies] are dramatic” (Eisinger 1995: 151). Thomas argues governments rely on business for economic activity to tax, as well as for job creation. Without these factors, they have neither the funds to carry out their jobs nor an economic performance that is likely to get them reelected. Thus, maintaining an adequate level of investment is a prerequisite for a government to meet any other goals it might have. (Thomas 2000: 24-5). Similarly, Noto argues that “if nothing else, subsidies allow politicians to take some decisive action and demonstrate that they care about attracting business to their jurisdiction” (Noto 1991: 256-7). This literature emphasizes the political objectives for state governments of subsidizing industry. The underlying argument, then, is that politicians are driven by an interest in attracting or maintaining companies in their jurisdictions in order to increase their chances of reelection. Comparative research on subsidies in OECD and European Union (EU) member states makes similar arguments to explain the demand for subsidies. Verdier (1995) explores the incentives of both governments and social groups in offering and demanding subsidies. He argues that politicians “maximize their chances of staying in power through deliberate use of subsidies and to structure the political debate and embed factor owners into stable policy 5 networks” (Verdier 1995, 5). His quantitative and qualitative analysis of OECD countries for the period 1986-1989 supports his argument that left governments offer subsidies favoring labor and right governments offer subsidies favoring capital.3 The broad implication of his argument is that state subsidies are tools for governments to increase their chances of staying in power. Zahariadis (1997) also argues that ideological orientation of the political parties in power and domestic socioeconomic factors such as unemployment influence the level of subsidies in the EU. A crucial difference between the literature on the American states and the literature on comparisons among industrial countries is the greater emphasis on international factors in the latter. For example, in exploring the reasons for EU governments to grant subsidies to their industries, Zahariadis (1997) tests for the impact of world markets and finds that trade deficits increase the overall level of subsidies to manufacturing sector. Zahariadis (2001) focuses on the effects of international competition on firms with specific assets in OECD countries in the period 1990-1993. He argues that industries with high asset specificity have higher costs of switching production in the face of international competition and thus they are expected to lobby more intensely for subsidies. He finds that the level of subsidies varies systematically with the degree of asset (factor) specificity employed in a national economy (Zahariadis 2001, 603). To summarize, comparative research on subsidies in OECD and EU countries focuses on factors such as unemployment levels, asset specificity of national industries, political ideologies of governments, and international economic factors in determining the level of subsidies. The discussions on the American regional development policies focus on the political attractiveness 3 Verdier grouped each category of subsidies in the OECD data depending on their factor content (Verdier 1996, 23). The group of subsidies favoring capital more than labor includes general investment, R&D, export and aid to SMEs. In the group of subsidies favoring labor more than capital, he includes retraining and subsidies to traditonal sectors like steel, coal and ship-building. 6 and job creating potential of subsidies. The current research tests both domestic and international explanations to account for the variation in subsidy levels in OECD countries. I assume that governments respond to societal demands to increase their chances of reelection. This is a reasonable assumption because in order to achieve any other kind of ideological or social goals they pursue, politicians need to be (re)elected for office. However, I also hold that they are constrained by international factors in offering subsidies. If governments are motivated to get reelected, maintaining high levels of employment would be an important concern for them. Creating employment and saving jobs are frequently cited by governments as reasons for industrial subsidies. In the literature on American state development policies, creating employment is cited as one of the most important reasons behind industrial support programs and is an indicator of success (Saiz 2001, 54). Anderson and Wassmer ask “after all, who has not heard the three reasons most often cited by politicians to justify a local economic development incentive program: jobs, jobs, jobs” (Anderson and Wassmer 2000, 1-2). We would expect that creating employment will be a bigger concern in times of high unemployment. Zahariadis argues that “governments can ill-afford not to pay attention to unemployment since it affects their electoral chances.” (Zahariadis 1997, 342). Studies looking at the impact of unemployment on subsidies, however, have contradictory empirical findings. Blais (1986) finds that in the 1980s subsidies increased along with unemployment rates in OECD countries. Zahariadis, on the other hand, does not find any systematic relationship between unemployment rate and subsidies across EU countries for the period 1981-1986 (Zahariadis 1997, 351). Given the contradictory findings of these studies, it is important for the current study to establish the impact of unemployment on subsidy levels in the 7 time period under concern here. The first hypothesis concerns the level of unemployment in a country. H1: The higher the level of unemployment, the higher will be the level of state support to industry. If governments seek reelection, we would also expect to see higher levels of subsidies before elections. There is a well-established literature on the tendency of incumbent governments to stimulate the economy by expansionary monetary and fiscal policies before elections in order to increase their chances of reelection (Alesina and Roubini 1992, Alesina, Roubini and Cohen 1997). This argument has not been made with respect to subsidies, but one could expect governments to use subsidies to provide benefits to their constituencies and boost their popularity especially before elections. H2: Governments will tend to disburse more subsidies in periods before elections. Political ideology is used as a factor to explain variations in the extent and type of government intervention in the economy. Garret and Lange argue, despite the constraining effects of globalization, that partisan politics influences the extent of government intervention in the economy (Garret and Lange 1991). Zahariadis argues “parties of the left generally exhibit a proclivity toward more state intervention in the economy. Such governments would therefore be more likely to favor subsidies for their own sake as a means of controlling and socializing more industries and to a greater degree” (Zahariadis 1997, 343). The expectation here, then, is that left-leaning governments will tend to disburse more subsidies then right-leaning governments. H3: Governments that lean towards the left are likely to disburse more subsidies. My paper also focuses on international constraints faced by the governments when making decisions to grant subsidies. Subsidies are a way for governments to deal with the pressures of increasing integration in world markets and thus, the subsidy issue falls under the 8 broader debate on globalization. The conventional wisdom on globalization suggests that the capacity and effectiveness of government intervention in the economy has been on the decline with increasing trade and capital mobility (Garret 2001, Berger 1996). Much of the academic research on globalization, however, emphasizes that trade liberalization increases citizens’ demand for compensation. These authors demonstrate that government spending increases in response to the inequality and insecurity associated with increasing trade liberalization and capital mobility (Cameron 1978, Ruggie 1982, Rodrik 1998, Quinn 1997).4 Rodrik, for instance, argues that more open economies have bigger governments because government spending has a risk-reducing role in economies open to trade (Rodrik 1998). Applying this argument to subsidies, Zahariadis claims that more intense competition from abroad leads to higher subsides (Zahariadis 1997, 343). He holds that governments are motivated to protect certain industries in the face of international competition, especially defense-related industries and industries that are considered vital to the economy’s long-term growth (Ibid, 343). Blais associates the increases in government support to industries with the general decline in tariff protection. He argues that through subsidies government “attempts in some degree to cushion the potential shock associated with trade” (Blais 1986, 15). He finds “subsidies to industry are more substantial in countries where tariff protection is weakest” (Blais 1986, 15). The argument here, then, would be that the more exposed the industry to international trade, the more the state is expected to play a risk-reducing role by granting subsidies. 4 Ruggie (1982) drawing on Polanyi (1944), explains the emergence of ‘embedded liberalism’ in Western countries in the post-war period. Cameron (1978) argues that small open economies of continental Europe were more likely to foster the emergence of strong labor unions and left parties, and that these in turn result in more demand for government transfers to ameliorate the risks associated with open economies. Rodrik (1998)) finds in a sample of 23 OECD countries that an economy’s exposure to international trade and the size of its government are positively correlated. Quinn (1997) finds that greater capital mobility is associated with higher levels of government spending in his 38-country sample from OECD and non-OECD countries. 9 The opposite argument with regard to the effects of trade is more plausible, however. As Zahariadis (1997) argues, some sectors of the economy may demand more subsidies, but overall, firms’ demand for subsidies may be declining with increased trade. One could argue that the more open the economy, the more likely it is that firms will have adjusted to international competition, and the less dependent they are on subsidies. Hathaway shows, through a theory of dynamic industry preferences, “how trade liberalization can increase the global competitiveness of firms, lower the potential costs of future trade liberalization, and thereby make producer groups less likely to demand trade protection” (Hathaway 1998, 584). International economic exposure stimulates domestic firms to adopt new technologies, and become more competitive by focusing production in areas where they are relatively more efficient and by reducing capacity (Hathaway 1998, 554, Frieden and Rogowski 199, 33). Thus “trade liberalization tends to reduce, rather than increase, industry demands for protection” (Hathaway 1998, 576). Applying her argument to subsidies, one can expect that higher trade exposure would decrease the demands for subsidies. H4: The more open an economy to international trade, the lower is the level of subsidies. There are other international factors that can influence the government decision to subsidize. There are emerging international agreements that seek to limit the level of subsidies granted by their members. These international regimes may increase the costs for governments to grant subsidies, if they have effective monitoring and enforcement mechanisms. They may also change firms’ calculations of the costs and chances of success of lobbying for subsidies. Both the WTO and the EU founding treaties target industrial subsidies and try to limit their use (WTO Agreement on Subsidies and Countervailing Measures, Treaty of the EU Articles 87-90). The 10 WTO system to regulate subsidies was established after 1995, so it cannot affect subsidy levels in the period covered by this study. The EU rules on state aid have been in force since the Treaty of Rome. Observers of the EU state aid policy argue that the European Commission has become very active in the implementation of the state aid policy since the mid 1980s (Smith 1998). All plans to grant subsidies by the EU member states have to be reviewed by the European Commission. The Commission can request a government to stop a subsidy program, if it decides that the subsidy in question distorts trade among EU members. It can also order governments to recover the subsidy from the firm if it declares the subsidy is illegal based on the rules of the Treaty, and can take the government to European Court of Justice if the government does not comply. Therefore, with these enforcement and monitoring mechanisms, the European Commission can affect the calculations of the member states in giving subsidies. The EU rules on subsidies can also affect the firms’ demand for subsidies. If firms see that their chances of success in getting subsidies are low due to international constraints on the government, they may decrease their efforts to lobby governments, since lobbying is costly. The expectation is, then, that subsidy levels in EU member states should be lower than the nonmembers. H5: Governments of the EU member states are likely to disburse lower levels of subsidies than non-member governments. To summarize, I argue that domestically, three factors could account for the level of subsidies: the level of unemployment, elections and ideology of governing parties. Moreover, a country’s openness to trade and constraining international regimes could also account for the variation the level of subsidies. In what follows, I test the impact of these five variables, the level 11 of unemployment, elections, the ideology of the governing party, the level of trade openness and constraining international agreements on the level of industrial subsidies, after a discussion of the research design and methodology used for testing these hypotheses. 4. RESEARCH DESIGN AND METHODOLOGY Data This paper tests the hypotheses discussed above on data from sixteen OECD countries for which data is available for the period 1989-1995. The countries under study here are Austria, Belgium, Czech Republic, Denmark, Finland, France, Germany, Iceland, Japan, Norway, Portugal, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, Turkey and the United Kingdom.5 Unfortunately, the OECD data does not include data on the United States and Canada, thus there are no cases from North America. However, it includes Japan and Turkey, which extends the geographical scope of the study beyond Western Europe. The total number of observations is 98 country years. A list of data sources is presented in Table 2 in the Appendix.6 Variables The dependent variable, state subsidies, is operationalized as state support to manufacturing industries as percentage of manufacturing GDP. This data is taken from the OECD Industry Committee’s publication Spotlight on Public Support to Industry (1998). OECD project covers “all types of selective financial government support to manufacturing industry at the central or sub-central level, or indirectly through intermediary institutions” (OECD 1998, 19). This means that non-financial support to manufacturing is not included in the data.7 This may lead to an underestimation of the level of subsides, since in-kind subsidies such as provision 5 For Austria, Belgium, Czech Republic, Germany, Japan, Portugal and Spain subsidy data is only available until 1993. For the remaining countries data goes until 1995. 6 Data used in this paper is available from the author. 7 OECD reports that “a methodology for measuring the Net Cost to Government for indirect support measures have not yet been developed” (OECD 1998, 20). 12 of real estate, goods and services at below-market prices may be significant. However, the data includes industrial support schemes such as export credits and guarantees, equity capital infusions, basic research, venture capital funds and tax credits, which is an improvement over previous OECD publications (Ibid, 19). The first independent variable, unemployment refers to the percentage of unemployed in civilian labor force in the country. The election is a dummy variable takes on the value 1 if there was an election during that year or in the first six months of the following year, and 0 otherwise. If an election takes place towards the beginning of a year, it is expected that the governing party would start distributing subsidies the year before, so both the previous year and the election year are coded as 1 in such cases. Party ideology is operationalized as the dominance of left or right parties in the parliament. It is measured as the share of total parliament seats occupied by the members of a governing left party.8 Trade openness is measured as the sum of the value of exports and imports of a country divided by its GDP, all measured in current prices. Finally European Union membership takes 1 if the country is a member of the EU in that given year and 0 otherwise. Table 1 in Appendix 1 summarizes descriptive statistics of the independent and dependent variables. The dependent variable, manufacturing subsidies as a percentage of manufacturing GDP, is transformed using a logistic function and estimated by a quasibinomial model.9 The level of manufacturing subsidies is taken to be a linear additive function of unemployment, elections, percentage of left party seats in the government, trade openness and EU membership. 8 This refers to the average of quarterly distribution of seats in the parliament. OLS model is not appropriate for truncated data like percentage scores that are bounded by (0, 100). Therefore, I transformed the percentages using the logistic transformation to provide an unbounded scale on the dependent variable. Because this transformation is not linear, I use a quasibinomial model to estimate the fixed effects of the independent variables on the dependent variable. The quasibinomial model is appropriate for continuous logistic variables (see King 1998). This was estimated using the statistical package R 1.6.2. 9 13 The data used in testing these models is a pooled cross-section and time-series data. Two problems commonly associated with such data are autocorrelation and heteroscedasticity. Autocorrelation occurs when error terms of the regression are not independent of one another. In time-series data, serial autocorrelation produces biased estimates of variances. Even though the coefficients are not biased, t-tests on the coefficients will be biased upwards and this will make inferences unreliable. An analysis for autocorrelation in the OECD subsidy data reveals that there is some temporal autocorrelation. The standard approach in dealing with this issue is adding lagged dependent variables in the equation. However, the data series is too short to allow for this option. Instead, I examined the residuals from the estimated model to determine whether they exhibited patterns which would reflect this mild temporal correlation. The estimated temporal correlation is 0.12, which is not significant. Spatial autocorrelation suggests that observations close to each other in space may be influencing each other. The consequence of spatial autocorrelation is similar to serial autocorrelation. Since the variance-covariance matrix of the estimated coefficients is biased, it is difficult to make reliable inferences. I examined the model for autocorrelation using both geographical proximity and trade among these countries as a measure of economic closeness.10 I found that there was no apparent spatial dependency that affects the reported results. Heteroscedasticity means that the error terms of the estimated equation does not have constant variation. Under heteroscedasticity, estimated parameters are not biased, but since the variance of the estimates are biased and inconsistent, inferences based on these will be 10 I examined this model for spatial correlation using the trade among the sixteen countries in 1993 as a measure of economic closeness. There is a correlation of 0.63 between the trade openness, for example, and the weighted average trade among these countries. However, including a spatial lag in this model has no effect on the results, and the spatial lag itself is the only insignificant variable in the regression. In addition, the purely geographical spatial lag based on the number of borders was also insignificant in a spatial lag formulation. 14 unreliable. Unfortunately, the data used in this analysis seems to suffer from heteroscedasticity.11 The error terms seem to increase over time. To correct for this problem, I calculated heteroscedasticity-controlled standard errors, which are reported in the regression tables. 4. RESULTS The results of the generalized linear regression of the dependent variable, manufacturing aid, on the independent variables are presented in Table 3. Since the reported coefficients are logged probabilities; we can interpret only the signs and the significance of the coefficients as reported in this table. Table 1: Factors that influence the level of state support to industry in OECD countries, 1989-1995. Variable Unemployment Elections Left Party Trade Openness EU Coefficient Standard Error 0.061 -0.283 -0.002 -0.003 -0.817 0.003 0.026 0.001 0.001 0.032 Quasibinomial dispersion parameter= 0.017 N= 97 Notes: Heteroscedasticity-controlled standard errors are reported. The regression results show that all independent variables are statistically significant at high confidence levels, and two of them, unemployment and EU membership have signs in the expected directions. The coefficients for these variables, unemployment and EU membership are also significant at the highest confidence levels among these five variables. The coefficient for the variable unemployment is positive and highly significant. Governments in countries that have 11 I checked for heteroscedasticity in the data by using a graphic display of the distribution of residuals around the estimated regression line. 15 higher levels of unemployment, all else being equal, are likely to offer higher levels of subsidies to their industries. The coefficient of trade openness is significant and negative. Countries that have higher levels of international trade are likely to have lower level of subsidies. The coefficient of the EU membership variable is negative and significant at very high levels. Thus, governments of the EU member states are likely to disburse lower levels of subsidies than nonmembers, which provide support for the argument that EU subsidy regime has been successful in curbing down subsidies. According to the regression results, coefficients of the variables elections and left party are statistically significant, but their signs are opposite of theoretical expectations. Contrary to my expectations, governments facing elections and governments that are left-leaning are likely to grant lower levels of subsidies. The explanation for this might be that governments facing elections reallocate their expenditures on subsidies into other means of spending that provide more direct benefits to their supporters. Left governments might also be more likely to spend more on welfare and labor market policies rather than subsidizing industries. More in-depth research is needed to uncover the impact of elections and left governments on subsidy levels. In Figures 2 and 3, I demonstrate the effects of unemployment and EU membership on subsidy levels. I use the statistical model discussed above, then simulate how predicted levels of subsidies change when we vary unemployment level in figure 2 and EU membership in figure 3. In Figure 2, I plotted a simulation to show the effects of unemployment on the level of subsidies. Left government seats and trade openness are kept constant at their mean values (19.7 and 61.5 respectively). It is assumed that the country is a member of the EU, and there are no elections underway. This graphical display demonstrates that a country with 5% of unemployment level spends 1.18% of its manufacturing GDP on subsidies, holding all other values constant, whereas 16 a country with 15% unemployment level spends 2.14%. If we repeat this simulation for non-EU members, with 10% higher unemployment, the level of subsidies increases from 2.6 % to 4.7 %. The model predicts that a country with 15% unemployment rate will spend almost twice as much as a country with 5% unemployment. 1.5 5 Percent Unemployment 1.0 15 Percent Unemployment 0.5 0.0 0 1 2 3 4 Projected Percentage Change in Manufacturing Aid Figure 2: The effect of unemployment on subsidies. Left government seats and trade openness are held at their mean values (19.7 and 61.5). It is assumed that the country is a member of the EU and there are no elections underway. Conditional on these values, the model predicts that as employment varies from 5% to 15 % subsidies increase from about 1% to 2 %. Figure 3 simulates the effects of EU membership on the level of subsidies. Here unemployment, left governing party seats and trade are held at their mean values (7, 19.7 and 61.5 respectively). It is assumed that there are no elections underway. This figure reveals that in EU member countries subsidies account for 1.33% of manufacturing GDP, while in non-EU 17 members they account for 2.95%. Non-EU countries spend more than twice as much of their manufacturing GDP on state subsidies compared to EU member states, holding all else constant. 1.5 EU Members 1.0 Non EU Members 0.5 0.0 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 Projected Percentage change in Manufacturing Aid Figure 3: The effect of EU membership on subsidy levels. Unemployment, left governing party seats, and trade are held at their mean values (7, 19.7, and 61.5 respectively) and it was assumed that no elections were underway. Conditional on these values the model predicts that an EU member country spends around 1% of its manufacturing GDP on subsidies while a non-EU member spends about three times this amount. I simulate the effects of the continuous independent variables, unemployment, left party seats in parliament and trade openness to show their marginal effects on predicted level of manufacturing subsidies. The graphs in Figure 3 represent these simulations. Unemployment has a strong effect on the predicted subsidy levels to the manufacturing sector, which reaches about 10% for extreme levels of unemployment. Trade openness and parliamentary strength of the governing left party have slight negative effects on predicted levels of manufacturing aid. For 18 these projections, variables are set at their historical means or medians in simulations (unemployment =7%, left coalition=20%, trade = 61; elections, EU membership=0). Excluded from the graphs in Figure 3 are the two binary variables, elections and EU membership. Elections also influence the level of subsidies negatively. A non-EU country in which there are elections underway spends 2.2% of its manufacturing GDP on subsidies, while if there were no elections, the same country would spend 3% on subsidies. An EU country under the same conditions would spend 1% when there are no elections and 1.3% when there are elections coming up. EU membership influences subsidy levels negatively. As discussed above, the level of manufacturing subsidies in non-EU states more than twice as much as EU members. ^ β = 0.06 ^ β = − 0.001 ^ β = − 0.002 10 10 10 projected manufacturing aid 15 projected manufacturing aid 15 projected manufacturing aid 15 5 5 5 0 0 0 0 5 10 15 20 Unemployment Level 25 30 0 20 40 60 Left Governing Coalition 20 40 60 80 100 140 Trade Openness Figure 1: There is a strong effect of the unemployment level on the predicted subsidy levels to the manufacturing sector, which reaches about 10% for extreme levels of unemployment. Conversely, neither trade nor the strength of the left governing party appear to have any strong effect on predicted levels of manufacturing aid. For these projections, variables are set at their historical means or medians in simulations (unemployment =7%, left coalition=20%, trade = 61; elections, EU membership=0). 19 How do the findings of this study fit with previous research in this literature? I find partial support for the underlying assumption that governments respond to domestic demands in order to increase their chances for reelection. One of the strongest findings is that unemployment leads to higher levels of subsidies. Governments use subsidies to stimulate the economy to create new jobs, which confirms Blais’s findings and contradicts Zahariadis (Blais et al. 1986, Zahariadis 1997). There is a strong negative relationship between EU membership and subsidy levels. EU members are more constrained than nonmembers in granting subsidies. This confirms the observations of some EU scholars that EU subsidy regime has been effective since the late 1980s (Smith 1998, Cini and McGowan 1998). Proximate elections and left party governments, contrary to my expectations outlined in Section two, are associated with lower levels of subsidies. The finding about elections contradicts with the literature on electoral cycles; however, it is possible that incumbent governments redirect subsidy expenditures towards other means of stimulating the economy. The negative relationship between left governments and subsidies also goes against the conventional wisdom that left governments intervene more in the economy. However, left governments might also be more inclined to spend on redistributive and labor market policies, rather than subsidies. I find that greater trade openness leads to a decline in subsidy levels. This supports the argument that international competition forces firms to become more competitive, therefore leads to lower demand and lower levels of subsidies. This could also suggest that governments are increasingly unwilling or unable to maintain their subsidy levels, as countries integrate into international markets. In this sense, my finding goes against the compensation argument that Rodrik (1998) and others have made. 20 How do the findings fit into the debate on globalization and national autonomy discussed in the introduction? The conventional view on globalization suggests that pressures for efficiency will reduce government spending and lead to a race to the bottom in most public services. In line with this efficiency argument, I find that greater exposure to trade results in lower levels of subsidies. However, viewed in the context of other findings of this study, the picture that emerges is not of a government that is overwhelmed by efficiency concerns with increasing integration in world markets. The fact that average level of subsidies has increased in the OECD during the period under study suggests that government spending is not completely scaled back. Governments also respond to social concerns like unemployment by granting subsidies, which suggests that they still use compensatory mechanisms to respond to risks associated with globalization. The picture of government that emerges from this study is a complex one that responds to domestic demand, international competitiveness and international rules. This is consistent with others who find that state responses to trade and capital market liberalization are more complicated than the efficiency or compensation arguments suggest (Garret 2001, Berger 2000). As Blais argues “the strategy [of governments] may not be as clear or coherent as some people would wish, but this ambiguity results from the political necessity of reconciling partly contradictory objectives, such as growth, stability and jobs, not to mention political-military considerations” (Blais 1986, 14). 5. CONCLUSION In this paper I analyzed the causes of variation in the level of subsidies in sixteen OECD countries for the period 1989-1995. I used pooled time-series cross-sectional data to test the influence of unemployment, elections, governing party ideology, trade openness and European 21 Union membership on the level of industrial subsidies in these OECD countries. The results of regression analysis show that unemployment positively affects subsidy levels, while elections, left governments, trade openness and EU membership influence them negatively. The OECD data on state support to industry used in this study covers the period until 1995. The OECD discontinued publication of subsidy data after its 1998 report (Steenblik 2002, 10). This precludes the possibility of extending the quantitative research to more recent years. However, discussions on subsidies within the EU and in the European financial press give insights into recent debates and events. There is evidence that most of the factors discussed in this paper continue to influence governments’ decisions to subsidize industries. One of the significant findings of this study is the impact of unemployment on the level of subsidies. Unemployment is still a very common argument governments use when granting subsidies. In 1999, the British government offered to grant the equivalent of $249 million in subsidies to Rover in order to save thousands of jobs in Birmingham, which was eventually prevented by the European Commission (Burt 1999, 6). In 2000, the British government argued that it offered regional subsidies to create employment and boasted creating 50,000 jobs in the last 3 years through its regional aid programs (The Economist 2000). Similarly, the German government maintains a costly subsidy program to maintain jobs in the coal-mining industry (The Economist 1997). The French government recently emphasized its concerns for jobs in its negotiations with the European Commission on the subsidy for the engineering firm Alstom (Dombey 2003, 29). This anecdotal evidence suggests that unemployment and the concern for creating and maintaining jobs is still influential in governments’ decisions to subsidize industries. 22 The analysis in this paper suggests that European Union membership was a significant constraining factor on the level of industrial subsidies. The European Commission, the EU body responsible for implementing the state aid policy of the Union has been actively trying to curb subsidies in member states since the mid-1980s. The Commission reports that since 1986, the average share of subsidies in member states dropped from 3% of to 1% of their GDP (Commission 1989, Commission 2001, 23). The Commission also reports a continuous declining trend in subsidy levels since 1993. It might be early to comment on whether the WTO Agreement on Subsidies and Countervailing Measures will be effective in limiting subsidies among its members. So far, however, even its requirement for notification of subsidy plans proved to be technically difficult due to the large number of member states. To create enforcement and monitoring mechanisms on subsidies at the level of the WTO would be much more of a challenge. In this sense, the EU might be an exception as an international subsidy regime, rather than the rule. This project reveals some of the factors that influence subsidy levels in industrialized countries in the period 1989-1995. Available evidence suggests that similar trends have been in place after 1995 as well. In a period when regional and international agreements try to regulate and limit the use of subsidies, it is valuable to know that governments subsidize industries more when unemployment levels are high. It is also important to note that international regimes regulating the use of subsidies can be influential on government decisions on subsidization. As a future research agenda, one could explore spending on subsidies in relation to other government spending. This could provide insights into the trade-offs governments have to make when allocating resources to subsidies and other types of spending, given increasing international pressures. One could also explore the variation in subsidies at the subnational 23 levels, especially in federal states. The OECD reports that sub-central share of total expenditure on subsidies in 1995 was 14% more than its share in 1989 among OECD countries (OECD 1998, 30). Subnational governments also face increasing pressures due to domestic and international trade competition and increasing capital mobility. It would be interesting to investigate to what extent they face similar incentives and constraints in granting subsidies. As globalization makes competition and cooperation between firms and governments more intense, subsidies will remain high on the agenda of both domestic and international actors, and scholars. 24 Appendix 1: Table A1: Descriptive Statistics for Variables in the Model Unit Minimum Value Maximum Value Mean Median percentage 0.1 10.1 1.942 1.30 index 16.31 138.30 61.45 63.46 percentage 0.2 22.40 6.964 6.60 dummy 0.0 1.0 N/A mode=0.0 Left percentage 0.0 52.0 19.7 20.0 EU dummy 0.0 1.0 N/A mode=0.0 Variable Manufacturing Subsidies Trade Unemployment Election Table A2: Data Sources Variable Source Manufacturing Subsidies OECD, Spotlight on Public Support to Industry (1998) Trade Penn World Tables [Online] Unemployment IMF, International Financial Statistics (1998) Election Comparative Parties Dataset, by Duane Swank [Online] Note: Swank’s data does not include the Czech Republic, Iceland, or Turkey. These were completed with data from Parties and Elections in Europe (http://www.parties-andelections.de/indexe.html). Left Comparative Parties Dataset, by Duane Swank [Online] EU European Union Online 25 Bibliography Alesina, A. and N Roubini. (1992) “Political Cycles in OECD”, Review of Economic Studies 59: 663-688. Alesina, A., N. Roubini and G.D. Cohen (1997) Political Cycles and the Macroeconomy, Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press. Anderson, J.E. and R.W. Wassmer (2000) Bidding for Business: The Efficacy of Local Economic Development Incentives in a Metropolitan Area, Kalamazoo, Michigan: W.E. Upjohn Institute for Employment Research. Berger, S. (1996) “Introduction”, in Suzanne Berger and Ronald Dore (ed.s), National Diversity and Global Capitalism, Ithaca and London: Cornell University Press: 1-25. Berger, S. (2000) “Globalization and Politics”, Annual Review of Political Science 3: 43-62. Blais, A., C. Desranleau and Y. Vanier (1986) A Political Sociology of Public Aid to Industry, Toronto: University of Toronto Press. Blais, A. (1986) Industrial Policy, Toronto: University of Toronto Press. Burnier, D. (1992) “Becoming Competitive: How Policymakers View Incentive-Based Development Policy”, Economic Development Quarterly 6 (1): 14-24. Burt, T. (1999) “Carmaker’s state aid opposed by rival Porsche”, Financial Times, 7 February, 6. Buss, T. F. (2001) “The Effect of State Tax Incentives on Economic Growth and Firm Location Decisions: An Overview of the Literature”, Economic Development Quarterly 15 (1): 90105. Cameron, D. R. (1978) “The Expansion of the Public Economy”, American Political Science Review 72 (4): 1243-1261. Cerny, (1995) “Globalization and the changing logic of collective action”, International Organization 49(4). Cini M. and L. McGowan. (1998) Competition Policy in the European Union, New York: St. Martin’s Press. Commission of the European Communities (1989) First Survey on State Aids in the European Community, Luxembourg: Office for Official Publications of the European Communities. Commission of the European Communities (2001) Ninth Survey on State Aids in the European Community, Luxembourg: Office for Official Publications of the European Communities. Dombey, D. (2003) “Tense times for commissioner”, The Financial Times, September 2003: 29. Economist (1997). “State Aid: The Addicts in Europe”, November 22: 75. Economist (2000) “A friend turned foe”, October 7. European Union Online. www.europa.eu.int Eisinger, P. K. (1988) The Rise of the Entrepreneurial State: State and Local Economic Development Policy in the United States, Madison, WI: University of Wisconsin Press. Frieden, J. and R. Rogowski (1996) “The Impact of the International Economy on National Policies: An Analytical Overview”, in R.O. Keohane and H. Milner (ed.s) Internationalization and Domestic Politics, New York: Cambridge University Press: 79107. Ford, R. and Suyker, W. (1990) “Industrial Subsidies in the OECD Economies”, OECD Department of Economics and Statistics Working Papers, no. 74. Paris: OECD Publications. 26 Garret, G. (2001) “Globalization and Government Spending around the World”, Studies in Comparative International Development 35 (4): 3-29. Garret, G. and Lange P. (1991) “Political Responses to Interdependence: what’s “left” for the left?” International Organization 45 (4): 539-564. Grant II, D. S., M. Wallace and W. D. Pitney. (1995) “Measuring State-Level Economic Development Programs, 1970-1992”, Economic Development Quarterly 9 (2): 134-145. Hathaway, O. A. (1998) “Positive Feedback: The Impact of Trade Liberalization on Industry Demands for Protection”, International Organization 52(3): 575-612 International Monetary Fund (1994) International Financial Statistics Yearbook, Washington, D.C., International Monetary Fund Publication Services. ______ (1998) International Financial Statistics Yearbook, Washington, D.C., International Monetary Fund Publication Services. ______ (2001) Government Finance Statistics Manual 2001, Washington, D.C.: International Monetary Fund Publication Services. King, G. (1989) Unifying Political Methodology: The Likelihood Theory of Statistical Inference, Ann Arbor: Michigan University Pres. Morici, P. (1996) Resolving the North American Subsidies War, Bangor, ME: FurbushRoberts Printing Co. Noto, N. A. (1991). “Trying to Understand the Economic Development Official’s Dilemma,” in D. A. Kenyon and J. Kincaid, ed.s. Competition among States and Local Governments, Washington, D.C.: The Urban Institute Press, 251-258. Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (1998) Spotlight on Public Support to Industry, Paris: OECD Publication Services. Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (1996) “Public Support to Industry: Report by the Industry Committee to the Council at Ministerial Level”, OECD Working Papers Vol. 4 no. 39, Paris: OECD Publication Services. Parties and Elections in Europe. [Online]. Available: http://www.parties-and-elections.de/indexe.html Penn World Tables. [Online]. Available: http://www.bized.ac.uk/dataserv/penndata/pennhome.htm Political Reference Almanac. [Online]. Available: http://www.polisci.com/almanac/nations.htm Quinn, D. (1997) “The Correlates of Changes in International Financial Regulation”, American Political Science Review 91: 531-552. Rodrik, D. (1998) “Why do more open economies have bigger governments?” Journal of Political Economy 106:5, 997-1031. Ruggie, J.G. (1982) “International Regimes, transactions and change: embedded liberalism in the postwar economic order”, International Organization 36 (2): 195-231. Saiz, M. 2001. "Using Program Attributes to Measure and Evaluate State Economic Development Strategies," Economic Development Quarterly 15 (1): 45-57. Smith, M.P. (1998) “Autonomy by the Rules: The European Commission and the Development of State Aid Policy”, Journal of Common Market Studies 36:1, 55-78. Steenblik, R. (2002) Subsidy Measurement and Classification: Developing a Common Framework, Paper presented at the OECD Workshop on Environmentally Harmful Subsidies, November 7, Paris. Available online: http://www1.oecd.org/agr/ehsw/SG-SD(2002)17.pdf 27 Swank, D. Comparative Parties Dataset. [Online]. Available: http://www.marquette.edu/polisci/Swank.htm Thomas, Kenneth P. (2000) Competing for Capital: Europe and North America in a Global Era, Washington, D.C.: Georgetown University Press. Verdier, D. (1995) “The Politics of Public Aid to Private Industry”, Comparative Political Studies 28(1): 3-42. Zahariadis, N. (1997) “Why State Subsidies? Evidence from European Community Countries, 1981-1986,” International Studies Quarterly 41(2): 341-354. Zahariadis, N. (2001) "Asset specificity and state subsidies in industrialized countries", International Studies Quarterly 45 (4): 603-616. 28