* Your assessment is very important for improving the workof artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download The Night Sky September 2016 - Bridgend Astronomical Society

History of astronomy wikipedia , lookup

Star of Bethlehem wikipedia , lookup

Archaeoastronomy wikipedia , lookup

Corona Borealis wikipedia , lookup

Dialogue Concerning the Two Chief World Systems wikipedia , lookup

Chinese astronomy wikipedia , lookup

Orion (constellation) wikipedia , lookup

Hubble Deep Field wikipedia , lookup

Canis Minor wikipedia , lookup

Aries (constellation) wikipedia , lookup

Auriga (constellation) wikipedia , lookup

Spitzer Space Telescope wikipedia , lookup

Constellation wikipedia , lookup

International Ultraviolet Explorer wikipedia , lookup

Malmquist bias wikipedia , lookup

Crab Nebula wikipedia , lookup

Canis Major wikipedia , lookup

Stellar kinematics wikipedia , lookup

Cassiopeia (constellation) wikipedia , lookup

Cosmic distance ladder wikipedia , lookup

Extraterrestrial skies wikipedia , lookup

Star formation wikipedia , lookup

Corona Australis wikipedia , lookup

H II region wikipedia , lookup

Astrophotography wikipedia , lookup

Corvus (constellation) wikipedia , lookup

Observational astronomy wikipedia , lookup

Aquarius (constellation) wikipedia , lookup

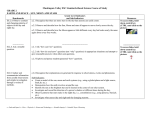

Perseus (constellation) wikipedia , lookup

BRIDGEND ASTRONOMICAL SOCIETY NEWSLETTER FUTURE TALKS AT 7.30 pm PYLE CHURCH HALL, PYLE NOV 11 "Overthrowing Newton -Proving Einstein right" by Dr Rhodri Evans of Cardiff University. DEC 2 “Star Men” Full length movie starring four “retired” British astronomers JAN 13th “The Moons of the Solar System” by Marc Delaney of Cardiff AS FEB "Neutron Stars and other extreme matter" by Professor Chris Allton of Swansea University MAR 10 “What has astronomy ever done for us?” by Dr Fraser Lewis of Cardiff University APR 14th “Planet 9” by Dr Bob Owens of the National Museum of Wales MAY 12th AGM The Night Sky November 2016 Compiled by Ian Morison Cambridge University Press has recently published two book by the author. 'An Amateurs Guide to Observing and Imaging the Heavens' is a handbook to bridge the gap between the beginner's books on amateur astronomy and the books which cover a single topic in great detail. Stephen James O'Meara and Damian Peach have both given it excellent reviews. 'A Journey through the Universe' covering our current understanding of the Universe (up to June 2014) was also published last year. Martin Rees has written a very nice review of it. Image of the Month Orion Constellation with Barnard's Loop and the Angel Fish Nebula Image: Ian Morison This image is just to attract some attention so that I can point you towards a wonderful website - The Photopic Sky Survey (www/skysurvey.org/survey/) It is the most beautiful image of the heavens that has ever been taken and was taken using 6 cooled CCD cameras to take over 37,000 frames which were combined into a 5 million pixel image. It took the photographer, Nik Risinger, travelling to some of the darkest sites in both hemispheres, a year to cover the sky. Do please visit his website! Highlights of the Month November early mornings: November Meteors. A Leonid crossing the Sword of Orion In the hours before dawn, November gives us a chance to observe meteors from two showers. The first that it is thought might produce some bright events is the Northern Taurids shower which has a broad peak of around 10 days but normally gives relatively few meteors per hour. The peak is around the 10th of November and, pleasingly, the Moon is first quarter on the 7th so, in the first week of November will have set by midnight. The meteors arise from comet 2P/Encke. Its tail is especially rich in large particles and, this year, we may pass through a relatively rich band so it is possible that a number of fireballs might be observed! The better known November shower is the Leonids which peak on the night of the 17th/18th of the month. Sadly, the Moon will be just after full so will hinder our view. As one might expect, the shower's radiant lies within the sickle of Leo and meteors could be spotted from the 15th to the 20th of the month. The Leonids enter the atmosphere at ~71 km/sec and this makes them somewhat challenging to photograph but its worth trying as one might just capture a bright fireball. Up to 15 meteors an hour could be observed if near the zenith. The Leonids are famous because every 33 years a meteor storm might be observed when the parent comet, 55P/TempleTuttle passes close to the Sun. In 1999, 3,000 meteors were observed per hour but we are now halfway between these impressive events hence with a far lower expected rate. Around the beginning and end of November (with no Moon in the sky): find M31 - The Andromeda Galaxy - and perhaps M33 in Triangulum How to find M31 Image: Stellarium/IM In the evening, the galaxy M31 in Andromeda is visible in the south The chart provides two ways of finding it: 1) Find the square of Pegasus. Start at the top left star of the square - Alpha Andromedae - and move two stars to the left and up a bit. Then turn 90 degrees to the right, move up to one reasonably bright star and continue a similar distance in the same direction. You should easily spot M31 with binoculars and, if there is a dark sky, you can even see it with your unaided eye. The photons that are falling on your retina left Andromeda well over two million years ago! 2) You can also find M31 by following the "arrow" made by the three rightmost bright stars of Cassiopeia down to the lower right as shown on the chart. Around new Moon (beginning and end of the month) - and away from towns and cities you may also be able to spot M33, the third largest galaxy after M31 and our own galaxy in our Local Group of galaxies. It is a face on spiral and its surface brightness is pretty low so a dark, transparent sky will be needed to spot it using binoculars (8x40 or, preferably, 10x50). Follow the two stars back from M31 and continue in the same direction sweeping slowly as you go. It looks like a piece of tissue paper stuck on the sky just a bit brighter than the sky background. Good Hunting! November 2nd - after sunset: Venus, Saturn and a thin crescent Moon Venus, Saturn and a thin crescent Moon Image: Stellarium/IM After sunset on the 2nd and seen in the west, a thin crescent Moon will lie above Saturn (magnitude +0.5) whilst over to the lower left will lie Venus (magnitude -4). November 5th - before sunrise : Jupiter lies below Porrima in Virgo Jupiter in Virgo above Porrima Image: Stellarium/IM Around one hour before sunrise looking towards the the East-Southeast, Jupiter will be seen lying in Virgo below Porrima, Gamma Virginis, and above Spica, Alpha Virginis. November 15th - late evening until sunrise: The full Moon close to the Hyades Cluster. The Full Moon in Taurus Image: Stellarium/IM During the night, the full moon will be seen moving away to the left of the Hyades Cluster in Taurus. Lying half way towards the cluster is the red-giant star Aldebaran. November 25th - one hour before sunrise: The third quarter Moon close to Regulus in Leo. The third quarter Moon in Leo Image: Stellarium/IM In the hours before dawn, the third quarter Moon will lie close (just over 3 degrees) to Regulus in Leo. NGC 891 imaged with the Faulkes Telescope Edge-on Image: Faulkes Telescope North. galaxy NGC Danial 891 Duggan Galaxy NGC 891, imaged by Daniel Duggan. This image was taken using the Faulkes Telescope North by Daniel Duggan - for some time a member of the Faulkes telescope team. NGC 891 is an edge-on spiral lying in the constellation Andromeda at a distance of 27 million light years. We think that this is very much as our own galaxy might look when seen edge-on. Learn more about the Faulkes Telescopes and how schools can use them: Faulkes Telescope" Observe the International Space Station The International Space Station and Jules Verne passing behind the Lovell Telescope on April 1st 2008. Image by Andrew Greenwood Use the link below to find when the space station will be visible in the next few days. In general, the space station can be seen either in the hour or so before dawn or the hour or so after sunset - this is because it is dark and yet the Sun is not too far below the horizon so that it can light up the space station. As the orbit only just gets up the the latitude of the UK it will usually be seen to the south, and is only visible for a minute or so at each sighting. Note that as it is in low-earth orbit the sighting details vary quite considerably across the UK. The NASA website linked to below gives details for several cities in the UK. (Across the world too for foreign visitors to this web page.) Find details of sighting possibilities from your location from: Location Index See where the space station is now: Current Position The Moon The Moon at 3rd Quarter. Image, by Ian Morison, taken with a 150mm MaksutovNewtonian and Canon G7. Just below the crator Plato seen near the top of the image is the mountain "Mons Piton". It casts a long shadow across the maria from which one can calculate its height - about 6800ft or 2250m. ` new moon first quarter full moon last q November 29th November 7th November 14th Novem The Planets Jupiter Jupiter is the only planet that can be seen in the pre-dawn sky this month rising some two and a half hours before the Sun at the start of November bit by ~ 2:20 UT (GMT) by the end of the month. On the first of November it will lie some 20 degrees above the south-eastern horizon an hour before sunrise and some 10 degrees higher by month's end. Though at its smallest and dimmest, it still has a magnitude of ~-1.7 and shows a 32 arc second disk. It remains in Virgo throughout the month and initially lies just 2 degrees below Porrima, Gamma Virginis, and sinks slowly southwards until by month's end it lies half way between Porrima and Spica, Alpha Virginis. With a small telescope, early risers should be able to see the equatorial bands in the atmosphere and the four Gallilean moons as they weave their way around it. Saturn Saturn is still visible low in the southwest after sunset, but is only some 10 degrees above the horizon 45 minutes after sunset. However as the month progresses it will sink lower and become harder to see. It lies in the southern part of Ophiuchus some 7 degrees up and to the left of Antares in Scorpius. One could not hope for a sharp view (but I am going to try using an Atmospheric Dispersion Corrector to help) but its wide open ring system should be seen. Sadly Saturn is moving towards the southern part of the ecliptic so for quite a few years will only be seen at low elevations - that is, of course, unless you travel to the southern hemisphere! Mercury Mercury shining at magnitude -0.5 and with a disk some 5 arcs seconds across becomes visible low in the southwest after sunset by the third week of November and slowly climbs higher in the sky until it reaches its furthest angular distance from the Sun in mid December. it might just be spotted close to Venus on the 23rd. Mars Mars, moving quickly eastwards through eastern Sagittarius and Capricornus dims from magnitude +0.4 to +0.6 during November. The red (actually salmon pink) planet can be seen low above the southern horizon throughout the month but, with a disk only ~7 arc seconds across, no surface features will be seen. Venus Venus sets some 2 hours after the Sun at the start of the month in the west but an hour later by month's end as it begins to dominate the evening sky. Its brightness increases from -4.0 to -4.2 magnitudes during the month whilst the angular size of its gibbous disk increases from 14 to 17%. As it does so its phase reduces from 78 to 70% which explains why the brightness changes so little. Venus is moving eastwards, leaving Ophiuchus on the 9th into Sagittarius where it passes over the Teapot and will be just 7.5 arc minutes below its 'lid' star, Lambda Sagittari (shining at magnitude 2.8) on the 17th. The Stars The Evening November Sky The November Sky in the south - early evening This map shows the constellations seen towards the south in early evening. To the south in early evening moving over to the west as the night progresses is the beautiful region of the Milky Way containing both Cygnus and Lyra. Below is Aquila. The three bright stars Deneb (in Cygnus), Vega (in Lyra) and Altair (in Aquila) make up the "Summer Triangle". East of Cygnus is the great square of Pegasus - adjacent to Andromeda in which lies M31, the Andromeda Nebula. To the north lies "w" shaped Cassiopeia and Perseus. The constellation Taurus, with its two lovely clusters, the Hyades and Pleiades is rising in the east during the late evening. The constellations Lyra and Cygnus Lyra and Cygnus This month the constellations Lyra and Cygnus are seen almost overhead as darkness falls with their bright stars Vega, in Lyra, and Deneb, in Cygnus, making up the "summer triangle" of bright stars with Altair in the constellation Aquila below. (see sky chart above) Lyra Lyra is dominated by its brightest star Vega, the fifth brightest star in the sky. It is a blue-white star having a magnitude of 0.03, and lies 26 light years away. It weighs three times more than the Sun and is about 50 times brighter. It is thus burning up its nuclear fuel at a greater rate than the Sun and so will shine for a correspondingly shorter time. Vega is much younger than the Sun, perhaps only a few hundred million years old, and is surrounded by a cold, dark disc of dust in which an embryonic solar system is being formed! There is a lovely double star called Epsilon Lyrae up and to the left of Vega. A pair of binoculars will show them up easily - you might even see them both with your unaided eye. In fact a telescope, provided the atmosphere is calm, shows that each of the two stars that you can see is a double star as well so it is called the double double! Epsilon Lyra - The Double Double Between Beta and Gamma Lyra lies a beautiful object called the Ring Nebula. It is the 57th object in the Messier Catalogue and so is also called M57. Such objects are called planetary nebulae as in a telescope they show a disc, rather like a planet. But in fact they are the remnants of stars, similar to our Sun, that have come to the end of their life and have blown off a shell of dust and gas around them. The Ring Nebula looks like a greenish smoke ring in a small telescope, but is not as impressive as it is shown in photographs in which you can also see the faint central "white dwarf" star which is the core of the original star which has collapsed down to about the size of the Earth. Still very hot this shines with a blue-white colour, but is cooling down and will eventually become dark and invisible - a "black dwarf"! Do click on the image below to see the large version - its wonderful! M57 - the Ring Nebula Image: Hubble Space telescope M56 is an 8th magnitude Globular Cluster visible in binoculars roughly half way between Albireo (the head of the Swan) and Gamma Lyrae. It is 33,000 light years away and has a diameter of about 60 light years. It was first seen by Charles Messier in 1779 and became the 56th entry into his catalogue. M56 - Globular Cluster Cygnus Cygnus, the Swan, is sometimes called the "Northern Cross" as it has a distinctive cross shape, but we normally think of it as a flying Swan. Deneb, the Arabic word for "tail", is a 1.3 magnitude star which marks the tail of the swan. It is nearly 2000 light years away and appears so bright only because it gives out around 80,000 times as much light as our Sun. In fact if Deneb where as close as the brightest star in the northern sky, Sirius, it would appear as brilliant as the half moon and the sky would never be really dark when it was above the horizon! The star, Albireo, which marks the head of the Swan is much fainter, but a beautiful sight in a small telescope. This shows that Albireo is made of two stars, amber and bluegreen, which provide a wonderful colour contrast. With magnitudes 3.1 and 5.1 they are regarded as the most beautiful double star that can be seen in the sky. Alberio: Diagram showing the colours and relative brightnesses Cygnus lies along the line of the Milky Way, the disk of our own Galaxy, and provides a wealth of stars and clusters to observe. Just to the left of the line joining Deneb and Sadr, the star at the centre of the outstretched wings, you may, under very clear dark skies, see a region which is darker than the surroundings. This is called the Cygnus Rift and is caused by the obscuration of light from distant stars by a lane of dust in our local spiral arm. the dust comes from elements such as carbon which have been built up in stars and ejected into space in explosions that give rise to objects such as the planetary nebula M57 described above. There is a beautiful region of nebulosity up and to the left of Deneb which is visible with binoculars in a very dark and clear sky. Photographs show an outline that looks like North America - hence its name the North America Nebula. Just to its right is a less bright region that looks like a Pelican, with a long beak and dark eye, so not surprisingly this is called the Pelican Nebula. The photograph below shows them well. The North American Nebula Brocchi's Cluster An easy object to spot with binoculars in Cygnus is "Brocchi's Cluster", often called "The Coathanger",although it appears upside down in the sky! Follow down the neck of the swan to the star Albireo, then sweep down and to its lower left. You should easily spot it against the dark dust lane behind. Brocchi's Cluster - The Coathanger The constellations Pegasus and Andromeda Pegasus and Andromeda Pegasus The Square of Pegasus is in the south during the evening and forms the body of the winged horse. The square is marked by 4 stars of 2nd and 3rd magnitude, with the top left hand one actually forming part of the constellation Andromeda. The sides of the square are almost 15 degrees across, about the width of a clenched fist, but it contains few stars visible to the naked eye. If you can see 5 then you know that the sky is both dark and transparent! Three stars drop down to the right of the bottom right hand corner of the square marked by Alpha Pegasi, Markab. A brighter star Epsilon Pegasi is then a little up to the right, at 2nd magnitude the brightest star in this part of the sky. A little further up and to the right is the Globular Cluster M15. It is just too faint to be seen with the naked eye, but binoculars show it clearly as a fuzzy patch of light just to the right of a 6th magnitude star. Andromeda The stars of Andromeda arc up and to the left of the top left star of the square, Sirra or Alpha Andromedae. The most dramatic object in this constellation is M31, the Andromeda Nebula. It is a great spiral galaxy, similar to, but somewhat larger than, our galaxy and lies about 2.5 million light years from us. It can be seen with the naked eye as a faint elliptical glow as long as the sky is reasonably clear and dark. Move up and to the left two stars from Sirra, these are Pi amd Mu Andromedae. Then move your view through a rightangle to the right of Mu by about one field of view of a pair of binoculars and you should be able to see it easily. M31 contains about twice as many stars as our own galaxy, the Milky Way, and together they are the two largest members of our own Local Group of about 3 dozen galaxies. M31 - The Andromeda Nebula M33 in Triangulum If, using something like 8 by 40 binoculars, you have seen M31 as described above, it might well be worth searching for M33 in Triangulum. Triangulum is the small faint constellation just below Andromeda. Start on M31, drop down to Mu Andromedae and keep on going in the same direction by the same distance as you have moved from M31 to Mu Andromedae. Under excellent seeing conditions (ie., very dark and clear skies) you should be able to see what looks like a little piece of tissue paper stuck on the sky or a faint cloud. It appears to have uniform brightness and shows no structure. The shape is irregular in outline - by no means oval in shape and covers an area about twice the size of the Moon. It is said that it is just visible to the unaided eye, so it the most distant object in the Universe that the eye can see. The distance is now thought to be 3.0 Million light years - just greater than that of M31. M33 in Triangulum - David Malin The constellation Taurus Taurus Taurus is one of the most beautiful constellations and you can almost imagine the Bull charging down to the left towards Orion. His face is delineated by the "V" shaped cluster of stars called the Hyades, his eye is the red giant star Aldebaran and the tips of his horns are shown by the stars beta and zeta Tauri. Although alpha Tauri, Aldebaran, appears to lie amongst the stars of the Hyades cluster it is, in fact, less than half their distance lying 68 light years away from us. It is around 40 times the diameter of our Sun and 100 times as bright. The Hyiades and Pleiades. Copyright: Alson Wong. More beautiful images by Alison Wong : Astrophotography by Alson Wong To the upper right of Taurus lies the open cluster, M45, the Pleiades. Often called the Seven Sisters, it is one of the brightest and closest open clusters. The Pleiades cluster lies at a distance of 400 light years and contains over 3000 stars. The cluster, which is about 13 light years across, is moving towards the star Betelgeuse in Orion. Surrounding the brightest stars are seen blue reflection nebulae caused by reflected light from many small carbon grains. These reflection nebulae look blue as the dust grains scatter blue light more efficiently than red. The grains form part of a molecular cloud through which the cluster is currently passing. (Or, to be more precise, did 400 years ago!) VLT image of the Crab Nebula Close to the tip of the left hand horn lies the Crab Nebula, also called M1 as it is the first entry of Charles Messier's catalogue of nebulous objects. Lying 6500 light years from the Sun, it is the remains of a giant star that was seen to explode as a supernova in the year 1056. It may just be glimpsed with binoculars on a very clear dark night and a telescope will show it as a misty blur of light. Lord Rosse's drawing of M1 Its name "The Crab Nebula" was given to it by the Third Earl of Rosse who observed it with the 72 inch reflector at Birr Castle in County Offaly in central Ireland. As shown in the drawing above, it appeared to him rather like a spider crab. The 72 inch was the world's largest telescope for many years. At the heart of the Crab Nebula is a neutron star, the result of the collapse of the original star's core. Although only around 20 km in diameter it weighs more than our Sun and is spinning 30 times a second. Its rotating magnetic field generate beams of light and radio waves which sweep across the sky. As a result, a radio telescope will pick up very regular pulses of radiation and the object is thus also known a Pulsar. Its pulses are monitored each day at Jodrell Bank with a 13m radio telescope.