* Your assessment is very important for improving the work of artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download Full article

Ketogenic diet wikipedia , lookup

Gastric bypass surgery wikipedia , lookup

Human nutrition wikipedia , lookup

Food politics wikipedia , lookup

Food studies wikipedia , lookup

Obesity and the environment wikipedia , lookup

Diet-induced obesity model wikipedia , lookup

Raw feeding wikipedia , lookup

Food choice wikipedia , lookup

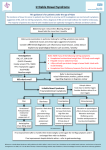

CLINICAL AND SYSTEMATIC REVIEWS nature publishing group 1 Food: The Main Course to Wellness and Illness in Patients With Irritable Bowel Syndrome William D. Chey, MD, AGAF, FACG, FACP, RFF1 Food sits at the intersection between gastrointestinal (GI) physiology and symptoms in patients with the irritable bowel syndrome (IBS). It is now clear that the majority of IBS sufferers associate eating a meal with their GI and non-GI symptoms. This is hardly surprising when one considers that food can affect a variety of physiologic factors (motility, visceral sensation, brain–gut interactions, microbiome, permeability, immune activation, and neuro-endocrine function) relevant to the pathogenesis of IBS. In recent years, clinical research has increasingly focused on diet as a treatment for IBS. There is a relative paucity of data from rigorous, randomized, controlled trials for any dietary intervention in IBS patients. Currently, the largest body of literature has addressed the efficacy of dietary restriction of fermentable oligo, di, monosaccharides, and polyols (FODMAPs). In the future, dietary treatments for IBS will move beyond the current focus on elimination to embrace supplementation with “functional” foods. Am J Gastroenterol advance online publication, 9 February 2016; doi:10.1038/ajg.2016.12 INTRODUCTION The ancient Greek philosopher and physician, Hippocrates, once said “Let food be your medicine and medicine be your food”. Early in the history of humankind, food was primarily viewed as a means of maintaining adequate nutrition. Over time, however, food has transcended its humble roots of nutrition, taking on important cultural and religious connotations. In the modern, developed world, food has become the focal point of many people’s entire day—most activities are planned around or viewed in relation to meal time. As getting enough to eat is no longer a primary concern for most residents of developed countries (indeed, billions are spent each year trying to help people to eat less…), food has transformed into one of our most important sources of entertainment and pleasure. Who would have ever guessed that Chefs like Jamie Oliver, Rachel Ray, Bobbie Flay, and Emeril Lagassi would become household names, reaching a level of notoriety on par with many famous athletes? Of course, our hero worship of Chefs reflects the modern trend of increasingly eating prepared or restaurant meals rather than home-cooked meals. Restaurants almost universally provide larger portions of calorie-dense foods, typically with less balance and diversity when compared with the home-cooked meal your mom would have prepared. “food as entertainment” has undoubtedly gotten us far from Hippocrates notion of “food as medicine”. However, attitudes regarding food are changing. This change in attitude has not been driven by health-care providers but by the general public. Despite a healthy degree of skepticism on the part of the medical community, billions of dollars are spent each year on dietary interventions and supplements, most of which are not supported by credible scientific evidence. The reasons for this behavior are complex but undoubtedly reflect growing frustration on the part of many patients with gastrointestinal symptoms for the usual solutions offered by traditional western medicine providers. The most common gastrointestinal (GI) condition diagnosed by gastroenterologists is the irritable bowel syndrome (IBS). IBS is a symptom-based diagnosis that requires the presence of abdominal pain and altered bowel habits (1). Similar to the clinical phenotype, the pathogenesis of IBS is heterogeneous with alterations in motility, visceral sensation, brain–gut interactions, microbiome, mucosal immune function, bile acid metabolism, and permeability having been implicated (2). Medical treatments for IBS typically target patient’s most bothersome symptoms and in methodologically rigorous randomized, controlled registration trials offer therapeutic gains of 8–20% over placebo and make half or less of patients better (2,3) (Table 1). With increasing frequency, patients are demanding more holistic solutions, including dietary and behavioral counseling, for their GI symptoms. DOES FOOD CAUSE IBS SYMPTOMS? Multiple survey studies have found that between half and three quarters of patients with IBS associate eating a meal with 1 Department of Internal Medicine, Division of Gastroenterology, University of Michigan Health System, Ann Arbor, Michigan, USA. Correspondence: William D. Chey, MD, AGAF, FACG, FACP, RFF, Department of Internal Medicine, Division of Gastroenterology, University of Michigan Health System, 3912 Taubman Center, SPC 5362, Ann Arbor, 48109-5362 Michigan, USA. E-mail: [email protected] Received 8 December 2015; accepted 31 December 2015 © 2016 by the American College of Gastroenterology The American Journal of GASTROENTEROLOGY REVIEW CME 2 Chey REVIEW Table 1. Primary end point data for FDA-approved medical treatments of IBS Drug Indication a Alosetron b Percentage response drug Percentage response placebo NNT 51 36 7 IBS-D Rifaximin IBS-D 43 34 11 Eluxadolinec IBS-D 27 17 10 Lubiprostoned IBS-C 18 10 12.5 Linaclotidee IBS-C 34 14 5 FDA, food and drug administration; IBS-C, irritable bowel syndrome with constipation; IBS-D, irritable bowel syndrome with diarrhea; NNT, number needed to treat, primary end points. a Adequate relief of IBS-D symptoms (33). b Adequate relief of IBS symptoms (34). c >30% Reduction in the mean abdominal pain score and the bristol stool form score of <5 on the same day for >50% of days during weeks 1–12 (35). d Monthly responder for ≥2 of 3 months. Monthly responder defined as having at least moderate relief for 4 of 4 weeks or significant relief for 2 of 4 weeks (36). e Each week, ≥30% decrease in worst abdominal pain+increase ≥1 complete spontaneous bowel movement from baseline for ≥6 of 12 weeks (37). triggering or exacerbating their IBS symptoms. Investigators from Sweden found that over 80% of their IBS patients associated their symptoms with food (4). Another study found a similar result, and both studies reported that IBS patients with food-related symptoms had reduced quality-of-life when compared with IBS patients whose symptoms were not related to food (4,5). Contrary to the accepted notion that fat is the primary culprit food, patients tell us that carbohydrates and proteins are actually more bothersome to them (4). food categories—i.e., low fermentable oligo, di, monosaccharides, and polyols (FODMAPs), gluten-free, elimination diets (8). Although a number of diet strategies have been suggested, the greatest number of studies has addressed the role of the low-FODMAP diet as a treatment for IBS (9). Further, there are a number of emerging dietary interventions that involve foods or food derivatives that can be taken, rather than eliminated, to improve symptoms or prevent disease (10,11). ELIMINATION: LOW-FODMAP DIET HOW DOES FOOD CAUSE GI SYMPTOMS? The mantra of researchers with an interest in nutrition is “food is complicated”. Doctors tend to think about food based on their content of carbohydrates, proteins, lipids, vitamins, and minerals. On the other hand, the USDA divides foods into five main groups—fruits, vegetables, grains, protein foods, and dairy (http://fnsweb01.edc.usda.gov/food-groups/). Within these categories, there are large differences in the effects that one food constituent vs. another will exert in the GI tract. Numerous factors beyond the actual content of an individual food including the combined effects of other foods consumed, meal volume, meal consistency, time of day the meal is consumed, and the host’s microbiome and mood all likely influence the likelihood of food to cause pleasure or pain. There is mounting evidence that food exerts effects on motility, visceral sensation, brain–gut interactions, microbiome, permeability, immune activation, and neuro-endocrine function—all key factors that have been implicated in the pathogenesis of GI symptoms (6–8) (Figure 1). WHAT ARE THE MAIN DIETARY STRATEGIES TO IMPROVE IBS SYMPTOMS? At present, the best evidence favoring dietary modification for GI symptoms has been accrued in patients with IBS. Most dietary interventions for IBS have focused on restriction of one of more The American Journal of GASTROENTEROLOGY FODMAPs are variable chain carbohydrates that are poorly or nondigested by the human small intestine and, as a consequence, reach the colon where they are fermented by the resident microbiome producing short-chain fatty acids and a number of gases including hydrogen and methane (12). Using a variety of techniques, numerous studies have reported qualitative and/or quantitative differences in the colonic microbiome identified from the stool of IBS patients compared with non-IBS controls (13,14). Although it is fair to conclude that the colonic microbiome found in IBS patients appears to be different than that found in nonIBS controls, the specifics of the differences identified have not been consistent from study to study undoubtedly related to a host of variables including diet, genetics, supplements, medications, psychological state, and methodological differences. Another critically important point is that these types of descriptive studies cannot decipher whether the observed microbiome differences are the cause or consequence of IBS. Understanding the functional consequences of the differences in colonic microbiome might lend some insight in this regard. A recent study from the University of North Carolina used wireless motility pH capsule testing to find that IBS patients had similar pH values in the small intestine but lower pH values in the colon than healthy volunteers, suggesting differences in colonic fermentation (15). These observations are relevant to the discussion of FODMAPs, which are poorly digestible/absorbable, carbohydrates that exert direct VOLUME XXX | XXX 2016 www.amjgastro.com Food and IBS 3 Bacterial fermentation Osmotic effects SCFA (Butyrate, propionate, acetate) Trophic effects Microbiome changes Luminal pH Gas production (CH4, H2, CO2) Increased osmotic load Increased biomass Acceleration of transit time Effects on: • Motility • Visceral sensation • Immune activation • Permeability GI symptoms • Pain • Gas/bloating • Altered bowel movements Cognitive and Emotional factors Adapted from Spencer M, et al. Cur Tx Opt Gl. 2014;12:424-440 Figure 1. How fermentable oligo, di, monosaccharides, and polyols cause IBS symptoms. osmotic effects and, as a consequence of colonic fermentation, create short-chain fatty acids and gas (16). Although FODMAPs are often referred to as a single group of carbohydrates, it is important to understand that they are a diverse group of carbohydrates that exert different effects in different parts of the GI tract. A recent study involving fMRI in healthy volunteers found that fructose led to secretion and distension of the small bowel, whereas the fructan inulin led to gas production and luminal distension primarily in the colon (17). A more recent study confirmed these findings in IBS patients, and unlike in healthy volunteers these were associated with the development of symptoms (18). Further, the changes in the luminal microenvironment induced by FODMAPs affect the gut microbiome (19–21) and may also affect bile acid metabolism, which has also been implicated in the development of symptoms in IBS patients (9). In IBS patients, many of whom have abnormalities in motility/transit and visceral sensation, the changes in luminal pH, water content of fecal contents, and luminal distention are more likely to trigger typical symptoms such as pain, cramping, bloating, flatulence, and altered bowel habits (18,22). Observational studies and a growing number of randomized, controlled trials suggest that the low-FODMAP diet leads to symptom improvement in between half and two-thirds of IBS patients (22–25). Although the diet appears to be effective for many IBS patients, it does not benefit otherwise healthy persons (22). Although most studies have found benefits of the low-FODMAP diet in IBS patients, a recent 4-week randomized trial from Sweden reported similar efficacy with the low-FODMAP diet and a diet intervention based on guidelines from the National © 2016 by the American College of Gastroenterology Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) and British Dietetic Association (BDA) guidelines (26,27). It is important to note that both interventions were delivered by a trained dietician and that the “control” intervention involved active recommendations, and thus this trial should be considered a comparative effectiveness trial rather than a placebo controlled trial (23). In one of the only studies with extended follow-up, an Italian group found that >70% of patients were willing to continue the low-FODMAP diet with a mean of 16-month follow-up (24). This study also reported no incremental clinical benefit but a decreased willingness to continue when a gluten-free diet was added to the lowFODMAP diet. Practical tips regarding the low-FODMAP diet for IBS can be found in Table 2. Many IBS patients will respond within 1–2 weeks of initiating the low-FODMAP diet (22,28). Indeed, some patients will respond within a few days of starting the diet. It can be difficult to unravel whether improvement is the consequence of physiologic effects or placebo. This usually becomes more apparent with continued use of the diet over the course of several weeks. Although many patients respond soon after initiating the diet, some patients can take 3–4 weeks to respond. It is critically important to understand that the low-FODMAP diet is a “blunt instrument”, which is intended to identify patients who are sensitive to FODMAPs. The full elimination phase is “not” intended to be a long-term treatment strategy. Patients who respond to the low-FODMAP diet should be instructed to systematically reintroduce foods that contain known FODMAPs. In this way, patients can determine whether their symptoms are the cumulative effects of all of the FODMAPs they are consuming or whether clinical The American Journal of GASTROENTEROLOGY REVIEW FODMAPs 4 Chey REVIEW Table 2. Practical pointers regarding the low-FODMAP diet for IBS Teaching is ideally provided with the assistance of a trained dietician. In the absence of a dietician, appropriately vetted books, web-based resources, and mobile apps can help patients implement the low-FODMAP diet in a medically responsible manner. A one-page handout is “not” sufficient to implement the diet. A 2–4-week trial is usually sufficient to gauge clinical response. Bloating and abdominal pain are the most likely symptoms to respond. Diarrhea is more likely to improve than constipation. The full low-FODMAP diet is “not” intended to last a lifetime. Responders should be instructed to implement a stepwise reintroduction of foods containing individual FODMAPs to identify triggers and allow diversification of their diet. The low-FODMAP diet is “not” intended for people who do not experience gastrointestinal symptoms. FODMAP, fermentable oligo, di, monosaccharides, and polyol; IBS, irritable bowel syndrome. response is driven by specific types of FODMAPs. Clinical experience tells us that most patients will be able to reintroduce some FODMAP-containing foods while maintaining adequate control of their symptoms. Allowing patients to broaden their food palate is likely to improve adherence and reduces concerns about the restrictiveness of full dietary FODMAP exclusion. Recent studies suggest that an important driver of response to any dietary intervention is interacting with a trained GI dietician—optimally one on one, but even group education sessions can be highly effective (25). It is important to draw a distinction between a general dietician who may or may not have training or experience in caring for patients with GI disorders and a GI dietician who has specialized training and spends a substantial proportion of her/his time caring for patients with GI disorders. At present, many gastroenterologists have access to a general dietician, but only a small percentage has access to a registered dietician with specialized GI training. Going forward, it will be important for professional societies and/ or health systems to create training opportunities to increase the number of GI dieticians. The introduction of web and app-based teaching tools offers another exciting, although untested, means by which to administer the low-FODMAP diet in a medically responsible way. A number of clinical and research priorities remain regarding the low-FODMAP diet. There is a pressing need for further methodologically rigorous, adequately powered, randomized, controlled trials from around the world to validate the efficacy of the low-FODMAP diet. There is also a need for trials that assess the long-term benefits and safety of the diet, as well as well-designed trials to provide a recipe for FODMAP reintroduction. There remain concerns about preliminary reports of alterations in the colonic microbiome with the low-FODMAP diet (29). Studies to understand the long-term effects of the diet on the microbiome and any associated functional/clinical consequences of these changes will be vitally important. Concerns have also been The American Journal of GASTROENTEROLOGY raised about the long-term nutritional consequences of intensive FODMAP exclusion. Such concerns underscore the importance of incorporating a GI dietician into the health-care team to assure that patients are using the diet in a medically responsible manner and to guide the gradual reintroduction of foods containing FODMAPs. On the flipside, it is interesting to speculate about the development of biomarkers, which might improve outcomes to diet therapies. For example, there may come a day when our rapidly expanding knowledge of the gut microbiome and/or the functional consequences of these changes through measurement of short-chain fatty acids or volatile gases can be leveraged to identify patients more or less likely to improve with different dietary interventions. Data from a recent study in children with IBS who responded to the low-FODMAP diet support this interesting possibility (21). These insights make clear the need for further research to better understand how FODMAP restriction benefits symptoms in patients with IBS. Although most of the current discussion is focused on the effects of FODMAP exclusion on the microbiome and fermentation, it is also possible that the clinical benefits of this diet are related to exclusion of proteins (contained by wheat and milk for example) rather than FODMAPs per se (30). FOOD AS MEDICINE: FUNCTIONAL FOODS AND MEDICAL FOODS As mentioned earlier, diet strategies to date have focused on elimination of culprit foods. On the horizon is a push to find foods or food derivatives with medicinal value. Two groups that fit this bill are “functional foods” and “medical foods”. A functional food has been defined by the Food & Agricultural Organization of the United Nations as “a foodstuff that provides a health benefit beyond basic nutrition, demonstrating specific health or medical benefits, including the prevention and treatment of disease”. Functional foods can be categorized as follows (31): • • • Conventional foods that contain bioactive components. Foods enriched or fortified with bioactive food compounds. Synthesized food ingredients such as “indigestible oligosaccharides” that provide a health benefit or serve as precursors to compounds that provide a health benefit. Medical Foods represent a regulatory category designated by the FDA Orphan Drug Act of 1983. To be designated as a medical food, a substance must be intended for the specific dietary management of a disease or condition. Medical foods do not require a prescription but are given under the supervision of a physician. To be a medical food, a product must (32). • • • Comply with FDA-labeling requirements. Comprise ingredients that are sage and comply with FDA regulations. Be specially formulated and processed (as opposed to naturally occurring). VOLUME XXX | XXX 2016 www.amjgastro.com The development of foods or food derivatives with medicinal value is likely to accelerate in the coming years. Of course, strategies that exclude culprit foods and those that supplement foods with potentially beneficial effects should not be viewed as mutually exclusive. After all, recall that carbohydrates in general and FODMAPs specifically are important prebiotics and that their exclusion from the diet decreases the abundance of potentially beneficial colonic bacteria (19–21). Providing prebiotics or probiotics along with exclusion diets might be a way by which to address such concerns. CONCLUDING REMARKS In recent years, diet and nutrition have enjoyed a renaissance in gastroenterology and, indeed, in medicine as a profession. Interestingly, this movement has been driven as much by the general public as by physicians and academicians. Although the “greatest generation” and “baby boomers” typically expected medications to solve their health issues, “Gen Xers” and “Millennials” are seeking more natural and holistic solutions to slow down the march of time, prevent disease, and address the health problems that do occur. A huge part of this seismic shift toward holism will involve diet. Large companies that have benefited from the gluten-free craze can attest to the riches that can be accumulated on the heels of people’s beliefs. Some will remember a show called the “The X-Files” that ran from 1993 to 2002. Although many of the story lines were quite fanciful involving extraterrestrials, El Chupacabra, Golem, Mutants, Vampires, and government conspirators to name a few. The show’s popularity drew from an intriguing cast and well-written stories that weaved in just enough “facts” to allow an active imagination to rewrite reality for an hour. As Fox Mulder used to famously say—“I want to believe”. Alas, the internet is awash with fad diets and supplements that have drawn from the “X-Files” playbook—attractive marketing sprinkled with just enough “evidence” to create a plausible story. For a general public who “wants to believe”, the temptation of the next “scientifically proven” miracle can be just too great. It is time for scientists, gastroenterologists, and other health-care providers to do the necessary research and to educate ourselves on what is fact and what is fiction and in so doing help our patients navigate the troubled waters of the new holistic world—the truth really is out there. We just have to be interested enough to find it. CONFLICT OF INTEREST Guarantor of the Article: William D. Chey, MD, AGAF, FACG, FACP, RFF. Financial Support: None. Potential competing interests: Consultant and Research funding provided by Nestle. REFERENCES 1. Longstreth G, Thompson WG, Chey WD et al. Functional bowel disorders. Gastroenterology 2006;130:1480–91. © 2016 by the American College of Gastroenterology 2. Chey WD, Eswaran S, Kurlander J. Management of irritable bowel syndrome. JAMA 2015;313:949–58. 3. Ford AC, Moayyedi P, Lacy BE et al. ACG monograph on the management of IBS and chronic constipation. Am J Gastroenterol 2014;109:S2–S26. 4. Bohn L, Storsrud S, Tornblom H et al. Self-reported food-related gastrointestinal symptoms in IBS are common and associated with more severe symptoms and reduced quality of life. Am J Gastroenterol 2013;108:634–41. 5. Nojkov B, Eswaran S, Chey WD. Dietary restrictions predict worse diseasespecific quality of life in patients with irritable bowel syndrome. Gastroenterology 2014;146:S199. 6. Farré R, Tack J. Food and symptom generation in functional gastrointestinal disorders: physiological aspects. Am J Gastroenterol 2013;108:698–706 7. Corley DA, Schuppan D. Food, the immune system, and the gastrointestinal tract. Gastroenterol 2015;148:1083–6. 8. Spencer M, Chey WD, Eswaran S. Dietary renaissance in IBS: has food replaced medications as a primary treatment strategy? Curr Treat Options Gastroenterol 2014;12:424–40. 9. Gibson PR, Varney J, Malakar S et al. Food components and irritable bowel syndrome. Gastroenterology 2015;148:1158–74. 10. Tilg H, Moschen AR. Food, the immune system, and the gastrointestinal tract. Gastroenterology 2015;148:1107–19. 11. Rajilic-Stojanovic M, Jonkers DM, Salonen A et al. Intestinal microbiota and diet in IBS: causes, consequences, or epiphenomena? Am J Gastroenterol 2015;110:278–87. 12. Shepherd SJ, Lomer MCE, Gibson PR. Short-chain carbohydrates and functional gastrointestinal disorders. Am J Gastroenterol 2013;108:707–17. 13. Bennet SM, Ohman L, Simren M. Gut microbiota as potential orchestrators of irritable bowel syndrome. Gut Liver 2015;9:318–31. 14. Simren M, Giovanni B, Flint HJ et al. Intestinal microbiota in functional bowel disorders: a Rome foundation report. Gut 2013;62:159–76. 15. Ringel-Kulka T, Choi CH, Temas D et al. Altered colonic bacterial fermentation as a potential pathophysiological factor in irritable bowel syndrome. Am J Gastroenterol 2015;110:1339–46. 16. Ong DK, Mitchell SB, Barrett JS et al. Manipulation of dietary short chain carbohydrates alters the pattern of gas production and genesis of symptoms in irritable bowel syndrome. J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2010;25:1366–73. 17. Murray K, Wilkinson-Smith V, Hoad C et al. Differential effects of FODMAPs (Fermentable Oligo-, Di-, Mono-Saccharides and Polyols) on small and large intestinal contents in healthy subjects shown by MRI. Am J Gastroenterol 2014;109:110–9. 18. Major GA, Pritchard SE, Murray K et al. A double-blind crossover study using magnetic resonance imaging shows that fructose and inulin mediate symptoms in IBS patients through different mechanisms: early increase in small bowel water versus late increase in colonic gas. Gastroenterol 2015;148:S55–6. 19. Staudacher HM, Lomer MCE, Anderson JL et al. Fermentable carbohydrate restriction reduces luminal bifidobacteria and gastrointestinal symptoms in patients with irritable bowel syndrome. J Nutr 2012;142:1510–8. 20. Halmos EP, Christophersen CT, Bird AR et al. Diets that differ in their FODMAP content alter the colonic luminal microenvironment. Gut 2015;64:93–100. 21. Chumpitazi BP, Cope JL, Hollister EB et al. Randomised clinical trial: gut microbiome biomarkers are associated with clinical response to a low FODMAP diet in children with the irritable bowel syndrome. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2015;42:418–27. 22. Halmos EP, Power VA, Shepherd SJ et al. A diet low in FODMAPs reduces symptoms of irritable bowel syndrome. Gastroenterol 2014;146:67–75. 23. Böhn L, Störsrud S, Liljebo T et al. Diet low in FODMAPs reduces symptoms of irritable bowel syndrome as well as traditional dietary advice: a randomized controlled trial. Gastroenterol 2015;149:1399–407. 24. Piacentino D, Rossi S, Alvino V et al. Low-FODMAP diet in irritable bowel syndrome patients offers more benefit than a low-FODMAP gluten-free diet in the medium- and long-term. results from a double-blind randomized controlled clinical study and follow-up. Gastroenterology 2015; Vol. 148:S119. 25. Whingham L, Joyce T, Harper G et al. Clinical effectiveness and economic costs of group versus one-to-one education for short-chain fermentable carbohydrate restriction (low FODMAP diet) in the management of irritable bowel syndrome. J Hum Nutr Diet 2015;28:687–96. 26. NICE guidelines for IBS: Available at https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ cg61/chapter/1-Recommendations. Accessed February 2015. 27. McKenzie YA, Alder A, Anderson W et al. Gastroenterology Specialist Group of the British Dietetic Association. British Dietetic Association The American Journal of GASTROENTEROLOGY 5 REVIEW Food and IBS REVIEW 6 Chey evidence-based guidelines for the dietary management of irritable bowel syndrome in adults. J Hum Nutr Diet 2012 Jun;25:260–74. 28. Azpiroz F, Hernandez C, Guyonnet D et al. Effect of a low-flatulogenic diet in patients with flatulence and functional digestive symptoms. Neurogastroenterol Motil 2014;26:779–85. 29. Lacy BE. The science, evidence, and practice of dietary interventions in irritable bowel syndrome. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2015;13: 1899–906. 30. Fritscher-Ravens A, Schuppan D, Ellrichmann M et al. Confocal endomicroscopy shows food-associated changes in the intestinal mucosa of patients with IBS. Gastroenterol 2014;147:1012–20. 31. Ross S. Functional foods: the FDA perspective. Am J Clin Nutr 2000; 71:1735s–8. 32. Morgan SL, Baggott JE. Medical foods: products for the management of chronic diseases. Nutrition Rev 2006;64:495–501. The American Journal of GASTROENTEROLOGY 33. Ford AC, Brandt LJ, Young C et al. Efficacy of 5-HT3 Antagonists and 5-HT4 Agonists in Irritable Bowel Syndrome: Systematic Review and MetaAnalysis. Am J Gastroenterol 2009;104:1831–43. 34. Pimental M, Lembo A, Chey WD et al. Rifaximin therapy for patients with irritable bowel syndrome without constipation. NEJM 2011;364:22–32. 35. Lembo AJ, Lacy BE, Zuckerman MJ et al. Eluxadoline for irritable bowel syndrome with diarrhea. NEJM 2016;374:242–53. 36. Drossman DA, Chey WD, Johanson JF et al. Clinical trial: lubiprostone in patients with constipation-associated irritable bowel syndrome-results of two randomized, placebo-controlled studies. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2009;29:329–341. 37. Chey WD, Lembo AJ, Lavins BJ et al. Linaclotide for Irritable Bowel Syndrome With Constipation: A 26-Week, Randomized, Double-blind, Placebo-Controlled Trial to Evaluate Efficacy and Safety. Am J Gastroenterol 2012;107:1702–12. VOLUME XXX | XXX 2016 www.amjgastro.com