* Your assessment is very important for improving the work of artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download PERICLES` RECKLESS MEGARIAN POLICY WAS

Liturgy (ancient Greece) wikipedia , lookup

Thebes, Greece wikipedia , lookup

Ancient Greek literature wikipedia , lookup

Theban–Spartan War wikipedia , lookup

Battle of the Eurymedon wikipedia , lookup

Athenian democracy wikipedia , lookup

List of oracular statements from Delphi wikipedia , lookup

Greco-Persian Wars wikipedia , lookup

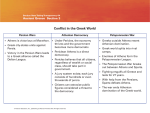

Spartan army wikipedia , lookup

PERICLES’ RECKLESS MEGARIAN POLICY WAS THE CENTRAL CAUSE OF THE PELOPONNESIAN WAR Stan Prager Student # 1058335 HIST531 K001 Fall 10 Research Paper January 25, 2011 PERICLES’ RECKLESS MEGARIAN POLICY WAS THE CENTRAL CAUSE OF THE PELOPONNESIAN WAR Introduction The year was 425 BCE. The great Peloponnesian War (431 BCE-404 BCE) between the rival alliances of competing hegemons Athens and Sparta, that would forever alter the landscape of ancient Greece in unrivaled catastrophe, was in its sixth year. Pericles – the celebrated leader of Athens in its Golden Age -- and perhaps a third of the population he once governed were dead in a devastating plague. Pericles’ defensive policy of securing the Athenian population within its impenetrable walls while Sparta sacked the surrounding countryside of Attica had failed; Athens was short on cash, the war was stalemated. That same year, Demosthenes, an Athenian strategos (an elected general) managed a surprise victory on the Peloponnesus at Pylos and entrapped hundreds of Spartans on the island of Sphacteria. Remarkably, Sparta (also known as Lacedaemon) sent a delegation to Athens to offer not only general peace terms but an offensive and defensive alliance in exchange for a cessation of hostilities and a return of the Spartans trapped on Sphacteria. This was an opportunity to end the war before the true horror and brutality that was to follow hardens the hearts of all concerned. Yet, the Athenians turned it down. Thucydides – the exiled general and great Athenian historian whose magisterial chronicle, The History of the Peloponnesian War, serves as a kind of bible for the conflict -reports that Cleon, the leading demagogue whom the historian clearly detests, rejects the opportunity for peace in order to pursue grander goals. Yet, if the text of Thucydides is read carefully, it becomes apparent that what Cleon actually did was to make counterproposals to Sparta that could not be honored: namely a return to the status quo ante during the time of 1 Athens’s greatest territorial sphere of influence during the heights of what later came to be called the First Peloponnesian War (460 BCE - 445 BCE) when Athens had control of Boeotia, north of Attica, as well as neighboring Megara. Perhaps there were negotiable points here – how much did Sparta really care about Boeotia, the Theban sphere of influence? But this would mean that the Spartans would have to abandon Megara – something that was impossible. As Dr. Donald Kagan, perhaps the leading historian of the Peloponnesian War in the twenty-first century puts it: “The suggestion that the Spartans might have been willing to give up Megara, or at least its harbors, however, was unrealistic . . . to have surrendered Megara would have placed the power of Athens directly on the isthmus and cut Sparta off from . . . central Greece . . . Clearly no such agreement was possible.”1 Where was Megara? What was its significance? Why would settlement of a destructive war that was devastating both sides hinge upon the status of what was actually a very tiny polis that bordered Athens? Thucydides history listed three direct causes of the Peloponnesian War, but insisted these were little more than pretexts. Instead he promulgated a kind of doctrine of inevitability and boldly claimed that: "The growth of the power of Athens, and the alarm which this inspired in Lacedaemon, made war inevitable."2 Still, he describes two of these “direct causes” – the Athenian clash with neighboring Corinth over the former Corinthian colony Corcyra, and the heavy handed way that Athens dealt with its own ally, Potidaea, another former Corinthian colony – in some detail. But the third cause he introduced, a kind of trade embargo issued against Megara termed the Megarian Decree, is treated only peripherally, with little emphasis and almost no elucidation, as if it hardly merited discussion. 1 Donald Kagan, Thucydides: The Reinvention of History (NY: Viking, 2009), 126-29. Thucydides, The History of the Peloponnesian War, 1.1.23, The Landmark Thucydides: A Comprehensive Guide to the Peloponnesian War. Edited by Robert B. Strassler. (New York: Free Press, 1996). 2 2 Thucydides also provides only scant detail on the First Peloponnesian War, the SpartanAthenian conflict of a generation before, which was detonated by the defection of Megara from the Spartan-led Peloponnesian League to the Athenian-led Delian League.3 The lack of focus upon the earlier war is striking and conspicuous in its absence: much as if a modern historian chronicling the rise of Hitler in the twentieth century lent scant reference to the defeat of Germany in the First World War. This paper rejects Thucydides’ inevitability doctrine, and will demonstrate that the central cause of the Peloponnesian War can be traced to the conflict over Megara, of which the Megarian Decree was but a device. Most studies of this kind focus primarily upon the Megarian Decree itself and the attendant politics of Pericles in this period. This paper will eschew this approach – this ground has been covered exhaustively by other scholars -- and instead devote itself to establishing the centrality of Megara as the vital strategic geography it represented to both sides by resurrecting its focal point in the First Peloponnesian War, where Megara’s status in the competing alliances was a dramatic pivot point. Moreover, it will demonstrate that Pericles’ Megarian policy was a reckless gamble deeply carved upon the ruins of that earlier war -- a gamble that was to have catastrophic consequences for Athens and ultimately for the wider Greek world. Megara Where was Megara and what was its significance in the politics of fifth century Greece? Megara was a very small (perhaps, by one estimate, 470 kilometers, or roughly 292 square miles) polis located on the Isthmus of Corinth between the poleis of Athens and Corinth which 3 Russell Meiggs, The Athenian Empire (London: Oxford University Press, 1972), 92. 3 due to its strategic geography secured an importance well out of proportion to its size.4 N.G. L. Hammond describes it as “. . . built on a barren limestone outcrop.”5 The soil was indeed poor. Isocrates quipped that the Megarians “farmed rocks.”6 According to Kagan: “The Megarians inhabited a small, infertile plain, with mountains on both ends … It could not produce enough grain to feed the 25,000 to 40,000 Megarians, but the highlands had enough vegetation to feed the flocks of sheep that produced Megara’s chief export: coarse, low-priced woolen coats.”7 Like Corinth but unlike Athens, Megara had ports on both the Corinthian Gulf (Pegae) and the Saronic Gulf (Nisaea), which fostered great wealth in trade relationships, although Hammond notes that Megara “. . . had a less convenient route than Corinth for portage across the Isthmus.”8 Not unsurprisingly, Megara’s economy was constructed upon a foundation of trade. Figure 1: The Megarid and its Environs9 4 Ronald P. Legon, Megara: The Political History of a Greek City-State to 336 B.C. (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1981), 22. 5 N.G.L. Hammond, A History of Greece to 322 B.C. (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1967), 12. 6 Isocrates, Speeches, 8.117 7 Donald Kagan, Pericles of Athens and the Birth of Democracy (NY: The Free Press, 1991), 69. 8 Hammond, 129. 9 William R. Shepherd, “Reference Map of Ancient Greece. Southern Part,” (cropped by the author) in Historical Atlas, 1926 ed., 14-15, Perry-Castañeda LibraryMap Collection, http://www.lib.utexas.edu/maps/historical/history_shepherd_1923.html, accessed 1/23/11. 4 Yet, Megara’s small size and location between two much greater powers made its security tenuous. Once dominated by Corinth, it established its independence in a war in the seventh century BCE, although not without a crippling loss to Corinth of its southern territory of fecund, arable land.10 Historically one of the four districts of Attica, it was nevertheless populated by Dorians rather than the Ionians of neighboring Athens. There was a tradition that Megara was once a part of a kingdom of Attica, yet Megarians spoke a different dialect than the rest of Attica.11 In the archaic period, Megara was “active in colonization,” a response to overpopulation, since the war with Corinth had “. . . robbed [them] of territory which was rich in pasture and timber.”12 Megara once controlled the important island of Salamis, and decisively defeated the Athenians in their first attempt to seize it, but eventually lost it to Athens in war shortly after 600 BCE.13 According to Plutarch, both the venerable Solon and Peisistratus (later tyrant of Athens) were involved.14 Hammond notes that: “. . . by 560 Peisistratus secured lasting possession of [Salamis] which was as vital to the future of Athens as the occupation of the southern Megarid was to Corinth. Henceforth Megara remained a small but valiant state, depending for survival upon astute diplomacy.”15 Not only Corinth and Athens competed for influence with Megara, but so did Sparta. Megara seems to have joined the loose Spartan confederacy later known as the Peloponnesian League as early as 519 BCE. Sparta may have been involved in the arbitration that finally 10 Hammond, 135. R.J. Hopper. The Early Greeks. (New York: Barnes and Noble Books, 1977), 60; Maurice Sartre. Histoires Grecques: Snapshots From Antiquity, trans. Catherine Porter. (Cambridge: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 2009), 9; Hammond, 78, 106-07. 12 Sartre, 22; Hammond, 134. 13 Tom Holland. Persian Fire: the First World Empire and the Battle For the West. (New York: Doubleday, 2005), 105;Barry Strauss, The Battle of Salamis: The Naval Encounter that Saved Greece – and Western Civilization (NY: Simon & Schuster, 2004), 60. 14 Plutarch, Lives: Solon, 8-10; Sartre, 49; Sealey, 123. 15 Hammond, 135. 11 5 awarded legal title of Salamis to Athens in 510 BCE, but Megara itself remained well within the Spartan sphere of influence.16 Notably, Megara joined both the Spartans and the Athenians to combat the Persian invasion in 480 BCE, ironically participating in a famous naval battle at the site of its former possession, the island of Salamis.17 Strategically, modern historians sometimes liken Megara’s geography with Belgium, as both served as a kind of open corridor for invasion.18 In Megara’s case, it was the “doorway” through which a hoplite levy could pass from the Peloponnesus into Attica to threaten Athens. Hammond underscores this: “Its strategic position is important. The main road from Boeotia to the Peloponnese runs through its territory, and it has ports . . . on the Saronic and Corinthian gulf.”19 Tom Holland describes it as “. . . a narrow and precipitous corniche hacked out of the flanks of coastal cliffs, and effectively the only land route that an army could follow to -- or from – the Isthmus.” Holland notes that during the first part of the Persian Wars when the Spartans contemplated abandoning the Athenians to their fate, they began “. . . demolishing the road to Megara . . .” to forestall Persian invasion from the north.20 That same route was also the only way for a land army to invade Athens. A friendly Megara could offer absolute security on land to Athens from this peril, as well as access to a western port on the Corinthian Gulf for both trade and military advantage over any rivals. A hostile Megara was not only a negation of those advantages, but actually an open avenue for invasion from the south. As such, Megara’s strategic location was to play a role of 16 Raphael Sealey, A History of the Greek City States 700-338 B.C. (Berkeley: University Of California Press, 1976), 147. 17 Holland, 255. 18 Kenneth Harl, Lecture 4: “Sparta and Her Allies” in The Peloponnesian War. (VA: The Teaching Company, 2007) Audio CD and Course Guidebook. 19 Hammond, 12. 20 Holland, 300. 6 some significance in both the first and the second Peloponnesian Wars. And this strategic value simply cannot be underestimated. Perhaps Ronald Legon sums it up best: Since it was impossible to travel by land from northern and central Greece into the Peloponnese without traversing the Megarid, its commercial and strategic importance was considerable. Megara was necessarily involved in all peaceful contacts and hostilities between the Peloponnesian states and the rest of mainland Greece, including a great many situations in which her role has been entirely ignored by historians. The issue constantly before the Megarians was whether to encourage, aid, obstruct, or ignore this traffic, weighing such factors as friendship, profit and security. Conversely, states that had a particular interest in securing safe passage through the Isthmus had also to consider how best to influence the Megarians’ behavior, whether through friendship, reward, intimidation, or outright coercion.21 The First Peloponnesian War As the era historians term the Pentecontaetia dawned following the defeat of Persia in 479 BCE, Megara was an ally of both Corinth and Sparta in the Peloponnesian League. Megara’s defection to Athens in 461 BCE due to an unresolved border dispute with Corinth launched the First Peloponnesian War. A paper of this size does not permit a comprehensive examination of the First Peloponnesian War, but an expanded outline is required in order to effectively put later events, and Megara’s place in these events, in the appropriate context. An alliance of convenience of Athens, Sparta and a limited number of other poleis – including Megara -- confronted the massive invasion by the Persian Great King Xerxes in 480 BCE that was to result in the sack of Athens. Unlikely victories by the Greeks at Salamis, Plataea and Mycale had by 479 BCE not only soundly defeated the Persians and guaranteed Greek sovereignty, but resulted in independence for most of the Ionian poleis on the coast of Asia Minor and left a newly confident Greece in charge of its own destiny, a destiny that included enforcing the peace with Persia. Sparta took the lead in this, but a variety of factors led 21 Legon, Megara, 33-34. 7 to a kind of passing of the baton to Athens, who formed a wide alliance of poleis in the Aegean that came to be called the Delian League, although it rapidly evolved into what can only be described as an Athenian Empire. The Athenian hegemony, based upon sea power, came to rub up against the traditional hegemony of land-based Sparta and its Peloponnesian League, a kind of looser alliance with some history which included Thebes, Corinth – and Megara. Despite this perhaps unavoidable chafing between the hegemons, they were rarely in direct conflict with one another and relations remained friendly, at least outwardly, especially while Cimon – a Spartan admirer and Athenian strategos who came to have a dominant political role – held primacy in Athens. This was to change when a devastating earthquake in Sparta provided an opportunity for a helot (Spartan state serfs/slaves) rebellion. Cimon led an Athenian contingent to aid the embattled Spartans, only to be turned away by Sparta for reasons that have prompted much speculation, but resulted in the humiliation and eventual ostracism of Cimon, and the rise to power of the leader of the radical democracy, Ephialtes. Ephialtes was soon assassinated and this leadership devolved to his protégé, the strategos Pericles who became the preeminent leader of Athens for years to come, and who -- unlike Cimon-- was no friend of Sparta. Soon, Sparta’s insult in sending away Cimon’s Athenian troops was repaid by the resettling of rebellious Spartan helots in a city on the Corinthian Gulf called Naupactus, where they would have their own polis, ever hostile to Sparta and its allies.22 According to Thucydides, this move by Athens was a deliberate swipe at Sparta “. . . because of their enmity towards the Spartans.”23 So relations between Sparta and Athens were rather cool when something quite unexpected occurred that shook Greece: Megara, a long-time Spartan ally and member of the 22 23 Donald Kagan, The Outbreak of the Peloponnesian War, (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1969), 9-78. Thucydides, 1.103.3. 8 Peloponnesian League rebelled and joined the Delian League. Megara, embroiled “. . . in a boundary dispute with Corinth, found themselves getting the worst of the war.”24 According to first century BCE historian Diodorus Siculus, Athenian entry into the conflict was to tip the balance of power and was very costly to Corinth, a key Spartan ally.25 It also ignited the First Peloponnesian War.26 The Athenians welcomed Megara into their alliance for both the enormous trade advantage of access to the Corinthian Gulf and the strategic coup of controlling the Megarid. As Kagan duly notes: “Control of the Megarid was of enormous strategic advantage to Athens. It made the invasion of Attica from the Peloponnese almost impossible; the control of Pegae [the Megarian port on the Corinthian Gulf] made it possible to supply Naupactus and control the Gulf of Corinth without making the long and dangerous voyage around the Peloponnese.”27 Sealey further underscores this: “. . . as long as the Athenians held the Megarid, they were secure against a Peloponnesian invasion of Attica and they were in a strong position to encroach on the Corinthiad or on Boeotia.”28 Elsewhere Kagan sums it up aptly: “An alliance with Megara would bring security against attack and thereby provide freedom to pursue opportunities wherever they arose.”29 Legon goes even further: “. . . there was hardly a more valuable prize for Athens in all of Greece than Megara.”30 Athens quickly exploited the opportunities that suddenly were available to her and devoted a focused effort to maximize these advantages and the strategic gains of controlling 24 Kagan, Outbreak, 80. Diodorus Siculus, The Library of History, Book 11.79.3. 26 Kagan, Thucydides, 44. 27 Kagan, Outbreak, 80. 28 Sealey, 262. 29 Kagan, Pericles, 70. 30 Legon, Megara, 185. 25 9 Megara. Suddenly, Athenian “. . . troops occupied Megara and Pegae.”31As Kenneth Harl describes it: “Megara was remodeled as a democracy, the city was fortified, long walls were built between Megara’s central city and its port Nisaea [the Megarian port on the Saronic Gulf] comparable to the long walls being built in Athens.”32 Now the Athenians would have control of the Isthmus by turning Megara into a “. . . land island.”33 More ominous for the Spartans perhaps, the Athenians also installed a garrison to secure Nisaea.34 As Kagan underscores: “This could only be interpreted as an act of war against the Spartans. Athens’ acceptance of a rebellious ally into the Athenian alliance, her fortification of the vital route between the Peloponnese and the rest of Greece were acts that Sparta could not tolerate.”35 This First Peloponnesian War was nothing like its later and greater namesake. For one thing, as Harl observes, “. . . the Athenians fought the Peloponnesians largely as a sideshow in comparison to other operations going on . . .” notably the ongoing clashes with Persia that saw Athens lending active support to several rebellions in the Persian Empire, included a significant effort to liberate grain-rich Egypt from Persian domination.36 The Egyptian rebellion was nothing short of “. . . a major commitment.”37 For another, as Harl stresses, control of Megara gave the Athenians “. . . an overwhelming strategic advantage . . . the Spartans could not invade Attica . . . So Megara’s importance comes out throughout this war.”38 31 Malcolm F. McGregor, The Athenians and Their Empire (Vancouver: University of British Columbia Press, 1987), 48. 32 Kenneth Harl, Lecture 11: “The First Peloponnesian War” in The Peloponnesian War. (VA: The Teaching Company, 2007) Audio CD and course guidebook. 33 Charles W. Fornara and Loren J. Samons II, Athens from Cleisthenes to Pericles (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1991), 89. 34 Sealey, 268; Thucydides, 1.103 35 Kagan, Outbreak, 80; Kagan, Pericles, 72. 36 Harl, Lecture 11. 37 Kagan, Outbreak, 81. 38 Harl, Lecture 11. 10 Despite Athenian focus on its wars within the Persian Empire, Sparta significantly does not do at all well in its engagements with Athens. Sparta launched a fleet to “. . . challenge Athenian control of Megara . . .” but was “. . . soundly defeated . . .” and Athens took control of the island of Aegina, a strategic Dorian ally of Sparta, so that Athens could now “. . . raid the Peloponnesian shores freely . . .” Later, the Athenians invaded central Greece, and installed democracies that were friendly to Athenian interests. So the Athenian position was very strong, and Sparta had good reasons to worry about the ultimate outcome. Utilizing the western Megarian port at Pegae as a launch point, in 454 BCE Pericles “. . . embarked 1,000 fighting men on 100 . . . ships . . .” and wrecked havoc on the Peloponnese.39 As Harl emphasizes: “. . . the Peloponnesians found themselves in 457 BC in a hopeless position where they could not wage any kind of effective war . . . and it was only because the Athenians were so busy fighting the Persians that the Athenians did not exploit these advantages and put an army in the Peloponnesus . . . and march directly on Sparta. And the danger that Sparta and her Peloponnesian allies faced is . . .” not to be underestimated.40 Athens’ winning streak was dramatically interrupted by a tactical and strategic disaster in Egypt that doomed its commitment to confrontation with Persia in that theater while spawning a series of rebellions elsewhere: “. . . in 454 the entire Greek force was destroyed, and Egypt was restored to Persian control . . . [which resulted in] serious unrest in the Aegean . . .”41 In the course of the long, complicated war, Athens’ fortunes rose and fell, but perhaps the lowest point occurred when a rebellion in Megara in 447/6 BCE overthrew the democratic government friendly to Athens, “butchered” the Athenian contingent, reinstated oligarchy and returned Megara to the Peloponnesian League – ironically with the assistance of Corinth, the 39 McGregor, 58; Kagan, Pericles, 85. Harl, Lecture 11. 41 Kagan, Outbreak, 97. 40 11 source of the original conflict!42 According to James McDonald: the massacre of the Athenians “. . . was an extraordinary act of betrayal which seems to have been contrived to win back the trust of Sparta and Corinth.”43 The war that began with Megara’s defection to Athens ended with its about-face and return to the Peloponnesian League.44 “The Megarian barrier blocking the road into Attica had been removed . . .”45 Shortly thereafter, Spartan hoplites marched through the strategic Megarian mountain passes and confronted Athens.46 Plutarch reports that Pericles negotiated a substantial bribe with an advisor of the Spartan king Pleistoanax to avoid hostilities; modern scholars are divided on the authenticity of this account.47 Whatever the reality, battle was averted, and the treaty of the Thirty Years Peace followed in 445 BCE, in which both sides made concessions to end the war. The return of Megara to the Peloponnesian League was integral to that treaty.48 The Thirty Years Peace and Beyond The Thirty Years Peace had something for both sides. For the Athenians, it was recognition of their position as hegemon and a license to control the poleis in their alliance with impunity. For the Spartans and their allies, it meant that Athens abandoned their budding land empire in Central Greece and returned Megara safely to the fold of the Peloponnesian League. 42 Harl, Lecture 11; Diodorus, Book 12.5.1; McGregor, 87; Hammond, 308; Thucydides, 1.114. James McDonald, “Supplementing Thucydides’ Account of the Megarian Decree” in Electronic Antiquities, (Volume II, Issue 3, 1994), 3, accessed at the Virginia Tech Digital Library and Archives “Electronic Antiquity” http://scholar.lib.vt.edu/ejournals/ElAnt/V2N3/mcdonald.html , accessed January 1, 2011. 44 Kagan, Thucydides, 43-45. 45 Kagan, Pericles, 120. 46 Thucydides, 1.114. 47 Plutarch, Lives: Pericles, 22; McGregor, 87. 48 Kagan, Outbreak, 124-128. 43 12 The treaty included arbitration, so in theory future conflicts between the hegemons could be resolved without resort to war.49 The peace held for almost fifteen years, a generation of hoplite soldiers, with no serious breach. Meanwhile, the Persian threat diminished so it was but a memory. Pericles was elected strategos repeatedly and came to occupy a position of prominence in the democracy far more consequential than that military title implied. He led Athens through what has been termed its “Golden Age,” diverting much of the contributions made by members of the Delian League – ostensibly to combat the Persians – to massive building projects, including the Parthenon. Athens became wealthy and powerful, while Sparta returned to the static, conservative political culture that characterized much of its history, content to not make war far from home lest the helots have another opportunity at uprising. Rivalries heated up, however, once Athens took some very aggressive steps in 435- 432 BCE that put them in direct conflict with Corinth, a key Spartan ally. This included intervention in a local affair between Corinth and its former colony Corcyra, and the Athenian heavy-handed behavior towards a former Corinthian colony, Potidaea, that was a member of the Delian League. Yet, the most provocative step was a Periclean policy known as the Megarian Decree. The Megarian Decree Much has made of the Megarian Decree, but this paper will devote the least amount of space to discussing the decree specifically and the purported intentions behind its enactment, largely because the details are surprisingly unimportant; rather the decree must be measured by its consequences. 49 Sealey, 291-94. 13 Historians are not certain of the precise terms of the decree, nor even exactly when it was legislated, but it appears that it was a trade sanction directed against Megara. In “. . . late 433 or early 432 BC . . . the Athenian assembly on the initiative of Pericles introduced . . .” what can only be described as an economic embargo against the polis of Megara, essentially banning the Megarians from trading in Athenian markets and ports, as well as any ports belonging to a member of the Delian League.50 Thucydides barely touches upon it, noting only that at the later Spartan assembly to hear grievances against Athens in 432 BCE, “. . . the Megarians called special attention to the fact of their exclusion from the ports of the Athenian empire and the market of Athens . . .” as well as a brief reference to the later Spartan willingness to back off hostilities if the Athenians revoked it.51 Since the Megarian economy was based upon trade and the Athenian Empire that controlled the Aegean would be closed to them under this decree, it would essentially put Megara out of business, lead to severe food shortages, perhaps even starvation. In short, the decree clearly “. . . threatened economic ruin for the Megarians.”52 Ian Worthington puts this into a modern perspective: “They were entirely dependant on trade for their livelihood. All of a sudden, not to be allowed to use the hundreds of ports belonging to allies in the Delian League and especially that of Athens . . . would be like closing off the whole of Asia to the USA today.”53 The various pretexts for the Megarian Decree included: “. . . the Megarians’ cultivation of sacred land claimed by the Athenians, their illegal encroachment upon borderlands, and their 50 Kenneth Harl, Lecture 18: “Outbreak of the Peloponnesian War” in The Peloponnesian War. (VA: The Teaching Company, 2007) Audio CD and course guidebook; Hammond, 320. 51 Thucydides, 1.67, 1.139.1-2. 52 McGregor, 128. 53 Ian Worthington, Lecture 26: “The Causes of the Peloponnesian War” in The Long Shadow of the Ancient Greek World (VA: The Teaching Company, 2009), Audio CD and course guidebook. 14 harboring of fugitive slaves.”54 It was also alleged that they murdered an Athenian herald.55 As E. Badian notes, such disputes with Megara should have been easy to resolve.56 But these alleged affronts were clearly a thin veil to cloak what was a punishing blow to a neighboring polis that came largely unprovoked, and obviously represented some kind of hidden agenda. Naturally, the Athenians were not fond of the Megarians; the first Peloponnesian War would be within most Athenian’s living memory, and that memory certainly would have included the fact that Megara switched sides and murdered the Athenians garrisoned there, this while Athens was at its weakest point in the war. Megara also contributed ships to the Corinthian side in a recent clash at sea that involved the Athenian navy in the conflict that swirled around Corcyra, but so did other Peloponnesian League members.57 Megara was part of the Peloponnesian League again under the terms of the Thirty Years Peace, and there was little context for the Athenian squeezing of Megara through this unique method of embargo, something that does not appear prior to this in the ancient world.58 All scholars seem to agree that Pericles was the force behind the Megarian Decree, and he was to stubbornly cling to it as the clock ticked towards war with Sparta, but as to his motives and his strategy there has been – and remains – only speculation. Dr. Kagan, Eduard Meyer, and numerous other scholars have often drawn bold lines between the events of the Peloponnesian War and conflicts of the modern era, while also attempting to read “ancient minds” with confidence. As M.I. Finley brilliantly points out: “It is significant that no two historians who 54 55 56 Kagan, Pericles, 208 Plutarch, Lives: Pericles, 29-30 E. Badian, From Plataea to Potidaea: Studies in the History and Historiography of the Pentecontaetia (Baltimore: John Hopkins University Press, 1993), n.234 57 58 Hammond, 318. Kagan, Pericles, 207. 15 study the causes of the Peloponnesian . . . War in that way ever agree, yet they can all quote Thucydides and Aristophanes with equal facility.”59 One might also ask: do Pericles’ intentions really matter? A minority of historians believe Pericles used the Megarian Decree to deliberately provoke war with Sparta.60 Kagan represents a view diametrically opposed to this, which holds that the decree was simply a tactic and should not be accorded very much weight.61 This author takes a position somewhat between these two extremes: that Pericles was not seeking to provoke war but that indeed the Megarian Decree was most consequential in its outbreak. Given this, exactly what Pericles had in mind is not that important, only that he zealously supported the Megarian Decree and even more zealously resisted its repeal, that Sparta viewed it as an act of aggression that could not be tolerated, and what followed was the great Peloponnesian War. In this sense, how Sparta perceived the decree is far more significant than the strategy it was based upon. As previously noted, Thucydides, who viewed all the war’s direct causes to be simply pretexts for its inevitability, hardly gives weight to the decree at all and barely mentions it, although according to Harl “. . . the rest of the surviving literary tradition . . . [makes it] . . . clear that the Megarian Decree was one of the major issues in the crisis during the summer of 432 BC which drove the Spartans to war.”62 Kagan suggests that because Thucydides’ thesis was that the war was inevitable, and because he admired Pericles -- and because the populace later blamed Pericles and his Megarian Decree for their wartime suffering -- the historian deliberately omitted 59 M.I. Finley, Ancient History: Evidence and Models (NY: Viking, Elisabeth Sifton Books, 1986), 85-86. Kagan, Outbreak, 262. 61 Kagan, Outbreak, 251-72. 62 Harl, Lecture 18. 60 16 all but superficial coverage of the decree in his account.63 Kagan goes so far as to accuse Thucydides of deliberate revisionism; indeed, the title of his most recent book is: Thucydides: The Reinvention of History.64 Harl concurs, adding that Thucydides essentially glosses over it because the decree “. . . was proposed by Pericles and was regarded as a colossal blunder on the part of Pericles.”65 Kagan, who also rejects Thucydides’ doctrine of inevitability, nevertheless generally admires Pericles; he sees Pericles as a centrist figure in the turmoil of Athenian politics, interprets his policies in the lead-up to the Peloponnesian War as essentially moderate compromises to keep the peace while protecting Athenian strategic interests, and dismisses the Megarian Decree as little more than a tactic, while acknowledging that its effect upon the Spartan audience was more dramatic.66 Other historians are not so sure. “At the very least . . . some see this action by Pericles “. . . as a strong warning to Corinth to back off on Corcyra.”67 Others see it for how it must have seemed at the time: a concerted effort to isolate Megara economically, rock their political world, perhaps force a change in government. Worthington argues that “. . . everyone knew that Pericles’ hidden agenda was to force Megara back into the Delian League . . .”68 With Megarians starving, what hope would they have but to defect again from the Spartan bloc and switch once more to an Athenian alliance? “. . . Thus Athens might regain the strategic advantage she held during most of the first Peloponnesian War.”69 Most significantly, it would put those strategic passes in the Megarid back under Athenian control. Robin Lane Fox is convinced this was indeed the goal: 63 Kagan, Thucydides, 58-74. Kagan, Thucydides. 65 Harl, Lecture 18. 66 Kagan, Outbreak, 251-72. 67 Harl, Lecture 18. 68 Worthington, Lecture 26. 69 Sealey, History, 318. 64 17 “The aim, surely, was to destabilize the Megarians’ ruling oligarchy indirectly, without actually declaring war. If the Megarians could be turned into a democracy, they might become allies of the Athenians. The . . . [First Peloponnesian War] had shown what a vital strategic ally they could be, as they could block their mountain-passes against Spartan invaders and close the natural route for invasions of Attica.”70 Harl emphasizes: “In effect, Megara could not trade in the Athenian empire and that meant Megarian ships could not sail to the Black Sea, and this is where Megarian trade interests lay. Without access to Athenian ports, no Megarian ship could ever leave Megara. That would mean that as the spring moved into summer there would be food shortages in Megara. At the very least there would be riots, and possibly a toppling of the government, and the replacement of the oligarchy by a government more friendly to Athens.”71 If Pericles’ intent was indeed to force Megara into alliance once more, his reckless strategy failed.72 Predictably, this was quite alarming to the Spartans, who “. . . took the precaution of installing a garrison at Nisaea.”73 This garrison underscores an earlier point: how Sparta perceived the decree is far more significant than its intent. And perhaps it points to something else, as well: Meiggs adds to the analysis a trenchant point that most scholars seem to have overlooked: “. . . by closing the harbours of the allies to Megarian ships . . . [Athens] was also interfering with the trading interests of those who traded regularly with Megara.”74 Legon underscores it: “Megara was the main economic link between the Peloponnesian states and the Aegean trading area. Any Athenian action which affected trade adversely could have a major 70 Robin Lane Fox, The Classical World: An Epic History from Homer to Hadrian (NY: Basic Books, 2006), 151. Harl, Lecture 18. 72 Sealey, 325. 73 Sealey, 325. 74 Meiggs, 266. 71 18 impact on nearby Peloponnesian states.”75 As Kagan -- often an apologist for Pericles – concedes, the Megarian Decree was “a blunder” that “. . . unlike any other Athenian action since 446/45 could be made to appear an act of aggression against a Peloponnesian state.”76 The ancients clearly held Pericles’ promulgation of the Megarian Decree directly responsible for the cause of the war.77 Perhaps modern efforts to flesh out the greater complexities of the conflict have moved too far a field to recognize the centrality of this event as the casus belli, much as modern scholarly attempts to describe the multiplicity of issues that led to the American Civil War sometimes overlook the absolute centrality of slavery to that struggle. Thucydides by fact and omission misleads his audience about the true nature of the decree, Pericles’ responsibility for it, and the perception of the Athenian population. But material intended for a different audience -- the contemporary satiric comedies of Aristophanes -- are often cited as clear indications that the Athenians blamed Pericles for the war, both in Peace (and especially in Acharnians, which describes in some detail the suffering of the Megarian people.78 Badian notes that: “Aristophanes, of course, is being satirical; but the facts on which he bases his satire must be true. since they were known to his audience.”79 In Acharnians, the Megarians are described as on the verge of starvation, and in one notable section of the play, a Megarian is so wretched he has dressed his daughters up as piglets that he attempts to sell to the protagonist, Dicaeopolis. For perhaps the sake of both comedy and pathos, the “. . . exchange plays on the double sense of . . . χοιρ α . . .” the ancient Greek word for piglet: “. . . a staple meat and sacrificial animal . . .” -- as well as the vulgar slang for 75 Ronald P. Legon, “The Megarian Decree and the Balance of Greek Naval Power,” (Classical Philology, Vol. 68, No. 3, Jul., 1973), 166 76 Kagan, Outbreak, 269. 77 Kagan, Outbreak, 254. 78 Badian, 144; Kagan, Thucydides, 36-37. 79 Badian, 144. 19 “hairless vulva . . .”80 The Megarian, in other words, is beyond desperate; he is willing to sell his daughters as prostitutes in order to feed his family. The hapless Megarian is reduced to this pathetic status by the war that has cut off access to Athenian markets, the same fate the Megarian Decree would have seen him condemned to. It seems clear from this that had Sparta not intervened, Megara would have had little choice to avoid famine but to capitulate to the Athenians to get the decree lifted, which would only have been accomplished through abandoning its affiliation with the Peloponnesian League and joining the Delian League, as it did in 461 BCE. This, as has been established thus far in this narrative, is something the Spartans could not and would not permit. The Path from the Megarian Decree to War With aggressive Athenian behavior in Corcyra and Megara further enflamed by the now besieged Potidaea, the Spartan assembly met to consider war. There were serious grievances all around and Corinth gave these the loudest voice, yet although Thucydides again barely touched upon it in his narrative, it was, in the final analysis, Pericles’ Megarian policy that was fundamental to the eventual declaration of war. Why was the Megarian Decree a central cause of the war? If one were to reject Thucydides’ assertion that the war was simply inevitable – as Dr. Kagan, this author and many scholars rightly do – then the immediate causes must be carefully examined. Without going into great detail over Corcyra and Potidaea, it is quite unconvincing that Sparta would go to war over these incidents, even if the Spartans were troubled and angry by evident Athenian aggression. 80 Aristophanes, The Acharnians, edited and translated by Jeffrey Henderson, [Cambridge: Harvard University Press, Loeb Classical Library 178, 2006] lines 735-750 and footnote #94, p.147; James Davidson, Courtesans & Fishcakes: The Consuming Passions of Classical Athens, [NY: Harper Perennial, 1999], 116-117. 20 And what of Potidaea? The Athenian action there was cause enough to bring a Spartan assembly to consider war, but there is little reason to believe Sparta would fight for Potidaea, especially since Athens was not technically violating the Thirty Years Peace: Athens could act as she would with her allies, however distasteful that might be. As Worthington acidly sums it up: “. . . the Spartans were pretty much indifferent to the woes of their allies. They really didn’t care about them because they weren’t being affected about what Athens was doing to Corcyra or Potidaea . . .”81 But Megara was a different story altogether. The Spartans that sat in assembly would have all been over thirty and therefore all would have had a living memory of the First Peloponnesian War. This memory would have to have included the threat to Spartan security and the concomitant impotence Sparta was faced with when Athens controlled those passes in the Megarid. Those Spartans would have to have recalled the frustration of their great land power’s inability to invade Attica while Athens the great naval power could act with impunity on the Peloponnese. It would not have been lost to them that in 432 BCE, Athens was both wealthier and stronger than it had been a generation before, prior to the Thirty Years Peace, and that this Athens was not engaged in multiple conflicts with the Great King of Persia. Permitting this stronger Athens control of Megara would surely tip the balance further. The Spartans simply could not allow that to happen. With this in mind Harl concludes forcefully with his “. . . contention that all the other issues were secondary and Corinth could never have gotten the Spartans to fight on any of them … but the Spartans would fight for Megara. And that’s because Megara held those strategic passes that allowed the Peloponnesian army movement into Attica and central Greece and the members of the Spartan citizen body who 81 Worthington, Lecture 26. 21 could vote, that is men over the age of 30, remembered very clearly what happened when Sparta lost those passes back in 461 BC.”82 There is a Spartan declaration of war, but actual combat does not break out for a full year; when it does, it is Thebes, the Boeotian ally of Sparta, that draws the first blood. If Sparta was eager for war, why the delay? In fact, several attempts to forestall open hostilities with Athens are reported in the sources. One obliquely seeks Pericles’ exile, another vaguely calls for freedom for the Greeks. But one offer from Sparta appears quite forthright: abandon the Megarian Decree and there will be no war. Everything else was on the table. As Kagan relates: “This proved to be the most significant grievance of the Peloponnesians, who, in the end, pronounced themselves willing to preserve the peace on the condition that the Athenians withdraw . . . [it]83 Plutarch underscores this: “. . . it seems likely that the Athenians might have avoided war on any of the other issues, if only they had been persuaded to lift their embargo against the Megarians . . .” He then goes on to relate an interesting anecdote that may be apocryphal yet manages to capture the essence of how far Sparta was willing to go to avoid war without relinquishing control of the Megarid to Athens. A Spartan diplomat was said to confront Pericles about the decree, to which Pericles replied that there was “. . . a law which forbade the tablet on which . . . [it] . . . was inscribed to be taken down. ‘Very well, then,” one of the envoys . . . suggested, ‘there is no need to take it down. Just turn its face to the wall! Surely there is no law forbidding that!’”84 The message seems clear: simply don’t enforce the decree and there will be no war. Finally, as Badian articulates so well: “. . . in the end Sparta was not concerned with her 82 Harl, Lecture 18. Kagan, Thucydides, 34. 84 Plutarch, Lives: Pericles, 29-30. 83 22 allies interests or even with her own promises, let alone with the strict terms of the Peace, but would have been satisfied with the cessation of Athenian moves against . . . Megara.”85 Pericles was immovable. He called for arbitration, as required by the Thirty Years Peace, but of course the legalistic Athenians through Pericles were careful to frame their provocative actions so as not to violate the letter of the treaty while certainly trampling over the spirit of it. Pericles remained adamant: there would be no compromise over Megara. In fact, he delivered a forceful oratory that seems to draw a kind of line in the sand over Megara: “I hope that you will none of you think that we shall be going to war for a trifle if we refuse to revoke the Megara decree . . .” and trumpeting “. . . the principle of no concession to the Peloponnesians . . . [lest it lead to] slavery.”86 This jingoistic hyperbole was effective: the Athenians voted to follow Pericles to war. Just as scholars cannot be certain what Pericles hoped to gain with the Megarian Decree, there can only be speculation as to why he so fiercely resisted its repeal. Whether he interpreted the Spartan delay in engagement as a sign of hesitation or even weakness, whether he was full of a false confidence based upon the twelfth-hour peace he negotiated back in 446 BCE, whether he fully expected the Spartans to offer a fourth olive branch, whether he simply boxed himself into a corner he could not emerge from – the result was the same. The Megarian Decree was dangerous to the point of recklessness. It would cost the Athenians thousands of lives, all of its treasure, all of its fleet, even its empire, and the world of Classical Greece would be forever altered for the worse by the terrible conflict that it engendered. 85 86 Badian, 160. Thucydides, 1.149-1.141. 23 Conclusion This paper opened with brief discussion of the events in 425 BCE that led Sparta to seek a peace treaty with Athens. This peace treaty that never was provides a solid date on a timeline of Megara’s relevance to the overall conflict, along with 461/460 BCE, when Megara’s defection from the Peloponnesian League led to the First Peloponnesian War; and with 447/446 BCE, marked by the Athenian loss of Megara that permits Spartan troops to invade Attica and hastens a settlement acceptable to both sides; and finally, with 432 BCE when the promulgation of the Megarian Decree brought on the Peloponnesian War. These four dates plotted together seem to point to an inescapable conclusion: Megara is a non-negotiable piece of property Athens covets and Sparta and will not relinquish whatever the costs on each side. Megara was a main cause of the first conflict and its status was a big piece of its settlement. Whatever his strategy, Pericles’ reckless gamble with the Megarian Decree became a combustible core that exploded into a conflict that was eventually to destroy him and the Athenian Empire he led. As for Megara, although it retained its independence and Athens suffered eventual defeat in the war, time would not heal its scars. Fox reports that: “More than 500 years later the [Roman] Emperor Hadrian still met memories of this famous feud. On visiting Megara, he found that, only recently in his reign, the Megarians had been refusing to allow Athenians and their families, ancestral enemies, into their houses.”87 Pericles’ Megarian Decree was to cut quite a deep groove into the history of Hellas. 87 Fox, 151. 24 BIBLIOGRAPHY Aristophanes. The Acharnians. Edited and translated by Jeffrey Henderson. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, Loeb Classical Library, 2006. Badian, E. From Plataea to Potidaea: Studies in the History and Historiography of the Pentecontaetia, Baltimore: John Hopkins University Press, 1993. Davidson, James. Courtesans & Fishcakes: The Consuming Passions of Classical Athens. NY: Harper Perennial, 1999. Diodorus Siculus, The Library of History, Book 11 and 12. Finley, M.I. Ancient History: Evidence and Models. NY: Elizabeth Sifton Books/Viking, 1986. Fornara, Charles W., and Loren J. Samons II. Athens from Cleisthenes to Pericles. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1991. Fox, Robin Lane. The Classical World: An Epic History From Homer to Hadrian. NY: Basic Books, 2006. Hammond, N.G.L. A History of Greece to 322 B.C. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1967. Harl, Kenneth W. The Peloponnesian War. Chantilly VA: The Teaching Company, 2007. Audio CD and Course Guidebooks. Holland, Tom. Persian Fire: the First World Empire and the Battle For the West. New York: Doubleday, 2005. Hopper, R.J. The Early Greeks. New York: Barnes and Noble Books, 1977. Isocrates. Speeches. 8.117 Kagan, Donald. Pericles of Athens and the Birth of Democracy. NY: The Free Press, 1991. Kagan, Donald. The Outbreak of the Peloponnesian War. Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1969. Kagan, Donald. Thucydides: The Reinvention of History. NY: Viking, 2009. Legon, Ronald P. Megara: The Political History of a Greek City-State to 336 B.C. Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1981. 25 Legon, Ronald P. “The Megarian Decree and the Balance of Greek Naval Power.” Classical Philology, Vol. 68, No. 3, Jul., 1973. McDonald, James. “Supplementing Thucydides’ Account of the Megarian Decree” in Electronic Antiquities, Volume II, Issue 3, 1994. Accessed at the Virginia Tech Digital Library and Archives “Electronic Antiquity.” http://scholar.lib.vt.edu/ejournals/ElAnt/V2N3/mcdonald.html.Accessed January 1, 2011. McGregor, Malcolm F. The Athenians and Their Empire. Vancouver: University of British Columbia Press, 1987. Meiggs, Russell. The Athenian Empire. London: Oxford University Press, 1972. Plutarch. Lives: Pericles. Plutarch. Lives: Solon. Sartre, Maurice. Histoires Grecques: Snapshots From Antiquity, Translated by Catherine Porter. Cambridge: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 2009. Sealey, Raphael. A History of the Greek City States 700-338 B.C. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1976. Shepherd, William R. “Reference Map of Ancient Greece. Southern Part,” (cropped by the author). Historical Atlas, 1926 ed., 14-15, Perry-Castañeda LibraryMap Collection. http://www.lib.utexas.edu/maps/historical/history_shepherd_1923.html. Accessed 1/23/11. Strauss, Barry. The Battle of Salamis: The Naval Encounter that Saved Greece – and Western Civilization. NY: Simon & Schuster, 2004. Thucydides. The History of the Peloponnesian War. The Landmark Thucydides: A Comprehensive Guide to the Peloponnesian War. Edited by Robert B. Strassler. New York: Free Press, 1996. Worthington, Ian. The Long Shadow of the Ancient Greek World. VA: The Teaching Company, 2009. Audio CD and Course Guidebooks. 26