* Your assessment is very important for improving the work of artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download Shakespeare`s scripts as blueprints for performance at

Antitheatricality wikipedia , lookup

Meta-reference wikipedia , lookup

Theatre of the Oppressed wikipedia , lookup

Theatre of France wikipedia , lookup

Augustan drama wikipedia , lookup

Theater (structure) wikipedia , lookup

Medieval theatre wikipedia , lookup

English Renaissance theatre wikipedia , lookup

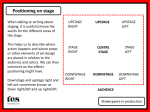

Colorado Shakespeare Festival wikipedia , lookup

Premier’s English Literature Scholarship Stripping the Bard bare— Shakespeare’s scripts as blueprints for performance at ‘The Wooden O’ Paul Macdonald McDonald College, North Strathfield Sponsored by PREMIER’S TEACHER SCHOLARSHIPS Focus of the study In the 400 years since their inception, Shakespeare’s scripts have been revisited, reinterpreted and reinvented to suit the contexts and tastes of an evolving theatre audience. Sometimes ‘bardolaters’1 have with noble reasons worked hard to hold the Bard’s texts aloft as revered utterances. Shakespeare’s plays, however, were never meant to be culturally weighty works but evolving scripts necessarily full of energy and variety to engage what would have been an eclectic and demanding crowd. Today’s students certainly need opportunities to visit Shakespeare’s works and to hopefully revisit, interpret, reinterpret and reinvent. It is paramount that they should also be given the opportunity to gain a sense of Shakespeare’s works as blueprints for performance within their original socio-historical contexts, to appreciate the scripts as being written for the ‘wooden O’ type framework of Elizabethan theatres such as The Rose and The Globe. And then, yes, students may take Shakespeare and make him their own! Theatre was spoken of in the same terms as brothels and animal baiting. We thus should be wary of such comments as those of critic Harvey who claims that a tragedy such as Hamlet was a play to ‘please the wiser sort’.2 Shakespeare was a shrewd audience-pleaser and he wrote to essentially please all types. He offered dramatic layers that would draw in crowds from all walks of life and thus hopefully raise profits for his shared company. What was crucially important—and we have in a sense largely lost this focus—was the power of language to delight. People came to listen rather than to watch Shakespeare’s plays, which offers a profound shift in our perceptions of Shakespeare’s plays. Keirnan3 has stated that to explore the relationship between dramaturgy and physical structure of a theatre, particularly as it was exploited by Shakespeare, ‘may take us beyond a limited and limiting definition of authenticity.’ And the experiences of performances at The New Globe have further illuminated what those first experiences of working within the physical structure of The Globe might have been like, what the Elizabethan groundlings and the ‘idle gallants’ 4 would have shared at 2 o’clock after the flag had gone up to signal the beginning of performances at The Globe. It is the aim of this paper to try to strip back the perceptions of Shakespeare’s now canonical works to see them as dynamic scripts for performance, as living texts that emerged from ‘earthy’ origins. So many of Shakespeare’s established techniques such as the invitation to the actor to play to the audience, the ‘attacking’ north-to-south entrances, the intimate soliloquy, choric speaking to the audience, the use of the aside, the grouping of characters (for liaison and repulsion) and his awareness of meta-theatrical conventions highlight the effort on his part to break down the barrier between actor and spectator. And it is of this incredible sharing of script between actor and audience at The Globe, the absence of what we now refer to as the fourth wall and the explicit self-reflexivity that students need to have a greater sense. As a result of the opportunity to research staging at the old and The New Globe settings, the following is an investigation of the original staging of Shakespearean plays. Students need to have a sense that Shakespeare may be read from a multitude of frameworks, but may also appreciate the works of the Bard as Elizabethan scripts that may be read as blueprints for performance on the stage of The Globe. If you like, they need to strip the Bard bare. As Kinney states: In ‘reading’ Shakespeare this way, we become collaborators with the playwright, too, just as his actors were.5 2 PREMIER’S TEACHER SCHOLARSHIPS Every writer must govern his pen according to the capacity of the stage he writes to. —The Printer to the Reader, The Two Merry Milkmaids, 1620 6 Shakespeare’s scripts should not be pigeonholed as historical texts that may not be tampered with. Rather, by appreciating Shakespearean scripts as blueprints for performance at The Globe, students may hopefully appreciate that the works of the Bard belong to the people. Pretensions may be stripped away and students should then not fear playing with what have since been deemed canonical texts. It is thus paramount that students have a strong sense of the performance of Shakespeare’s plays within their original socioeconomic context at The Globe Theatre. By appreciating the performance of Shakespeare’s scripts within Elizabethan times, students may then be more willing to reinvent Shakespeare for their own contexts. The Globe was built in 1599 after the existing theatre across the Thames, The Theatre, was dismantled as a result of the termination of a 21-year lease signed in 1576. Although not built until 1599, most of Shakespeare’s plays were written with the structure of The Globe or The Rose in mind, the latter playhouse probably offering the same structure, an amphitheatre space. The New Globe, completed in 1995, has further offered an amazing learning experience. Apart from what we have gleaned from diagrams, diary entries, the archaeological site of The Rose (excavated in 1989) and supposition, we have learnt much from the playing at The New Globe, what Kiernan describes as ‘a theatre for the twenty-first century built as close to modern scholarship so far could get to the sixteenth century original’.7 The actor playing Hamlet in 1601 would have walked onto the stage of The Globe, a 14-sided hatched polygon with irregularly shaped sides. The actor walked under the sky in the open amphitheatre, on a platform that felt out of doors in comparison to today’s modern theatres. Standing on the stage platform which was possibly 40 metres across, the actor could see a ground space before him, with raked yard where the groundlings stood, sloping downwards for drainage and also to help view-lines. There would have been three storeys of seating around, the theatre like its neighbour The Swan, able to hold up to 3000 people at any one time. Note that there were no toilets. At the back of the stage was a wall fronting the ‘tiring house’ (attiring or dressing area). The front of this tiring room was perhaps used as a discovery space, according to theorists such as Kinney, acting as an acting space for such settings as a cave, an apothecary shop or tomb (this is considered less certain because of limited view-lines for many in the audience). The back of the stage gave access to the playing area by two or more doors on either side and a balcony above. There were two stage doors, so Pericles’ stage directions tell us - ‘one door’, ‘the other’. There was a curtained area - ‘an arras’ - that Polonius, stood behind. We also know there was a trapdoor, which was needed for Hamlet in the grave scene and for Malvolio’s cell in Twelfth Night. The popular perception of the stage is the inclusion of a balcony, the balcony scene from Romeo and Juliet part of our collective consciousnesses. This was probably also used by musicians who, as 3 PREMIER’S TEACHER SCHOLARSHIPS discussed later, were very significant contributors to the playgoing experience. Above the balcony, or ‘terras’, was a cover, or ‘heavens’, supported by two pillars. These pillars, while controversial with players at The New Globe, were used as trees or for spying; their presence often signalled within the text by ‘steps aside’ (for instance, Berowne in Love’s Labour’s Lost). The cover over the stage was perhaps more to protect the costumes than the actors. Rain or not, the performances went on, but the bulk of the company’s money went into the wardrobe - therefore, the clothing needed to be protected. The underside of the stage ceiling was probably painted with the sun, moon and stars and probably with the signs of the zodiac. There was a trapdoor in the stage ceiling to drop down ‘angels’ and others. The intimacy of the Elizabethan stage offered possibilities for shared experience on the part of the audience since there were no physical or psychological barriers. As Kiernan states, the groundlings could become ‘an angry mob, a fearsome army, (or) a threatening force to those on stage’.8 The opportunity afforded by the physical conditions of the space for eye contact between actor and playgoer was to become the most significant element of the transformation in the actor-audience relationship which took place when the first full scale production took place at The New Globe Theatre. Because of the absence of the fourth wall that was born with realism, we relate to each of the figures on the stage in a number of different ways simultaneously. We relate to them ‘as characters in a fiction, as real people moving and talking close to us, and as actors, who are at once both real and fictitious, and neither’.9 The audience was drawn from all classes so Elizabethan plays needed to appeal on many levels. A major factor for the interactive audience response may be that the audience were not in the dark at The Globe. This inversion in terms of lighting becomes quickly apparent at The New Globe. The audience are in the spotlight, the playgoers highly visible to the actors on stage and more importantly the playgoers are highly visible to each other. Again the result seems to be a strangely empowering and energising experience according to Kiernan.10 The Elizabethan audience was also an oral audience, having grown up on sermons and other formalised public speech-audiences were used to those conventions left over from medieval theatre where the mystery, miracle and morality plays sermonised. Today’s audience is much more visually literate, which has obvious implications for staging Shakespeare today. Because there was no controlled lighting to ‘spotlight’ the experiences on stage, what the audience heard often became more important than what was seen. Remember that the Lord’s rooms, considered the best for seating, have the worst sightlines but offer the best position in terms of acoustics - supporting the Elizabethan preoccupation with sound rather than sight. In The Two Merry Milkmaids (1619), the Prologue calls the groundlings to order: We hope for your own good, you in the yard Will lend your ears attentively Things that shall flow so smoothly to your ear. Use of the stage at The Globe Shakespeare’s dramaturgy always has a practical basis. He had commonsense and understood what people wanted in the theatre. The variation of pace, the contrasting moods and the swift scene changes are dramatically effective but ultimately make sense as practical necessities to heighten audience involvement. Shakespeare certainly knew how to write plays that worked on stage at The Globe because he had a profound sense of the capacity of that stage. A number of specific factors influenced Shakespeare’s stage choices. Staging implications of a repertory system Probably the major factor influencing the staging of plays at The Globe was the repertory system. The Admirals 1594–95 season, for instance, performed six days a week offering the audience a 4 PREMIER’S TEACHER SCHOLARSHIPS total of 38 plays, of which 21 were new, added at more or less fortnightly intervals. Two of the plays were performed only once and only eight of the plays survived to the next year’s program. There are records of eight different plays over a 14-day period. There was no director as we might expect today either. Thus it was an intense experience further complicated by actors assuming multiple roles. The repertory system also demanded no or minimal sets because it would have been too difficult and too expensive to change sets. Rather settings were signalled by words, through numerous allusions to the natural elements and a range of exotic countries so that the audience might be transported via the imagination to other places and times, leaving the relatively featureless stage behind. Costumes and music become all important in place of lack of sets, as will be discussed later. Stage realism did have its layers. We know that sponges soaked in vinegar were concealed in the armpit and squeezed to produce the semblance of blood. Feigned hangings always received a big audience reaction. And spectacle, wherever possible, ruled. Audiences would have witnessed fireworks on occasions, descents through the heavens and the use of trickery and illusion (such as reversible top tables in banquet scenes such as in The Tempest. We also know that canons were used on occasions from the upper rooms since the fire that destroyed The Globe in 1613 was created by a canon shot during a performance of Henry VIII. The stage itself The Globe offered a fluid stage, what Kinney refers to as an ‘essential emptiness’.11 The scripts, in a sense, were spatially neutral, defined by the text itself. As Bernard Beckerman states: The actors did not regard the stage as a place but as platform from which to project a story, and therefore they were unconscious of the discrepancy between real and dramatic space.12 The stage thus offered the capacity for an infinite variety. With little or no attempt to achieve a mimetic verisimilitude, greater was the opportunity for ‘place’ to become invested with significances beyond mere physical existence. We thus often witness the juxtaposing of private and public spaces because the unadorned space allowed for this. This freedom is drawn from the tradition of medieval staging in which a pageant wagon with a formal platform, the locus, was in constant dialogue with the space below, bordering on the audience and given to more informal, and even intimate, shared speech, the platea. On The Globe stage, downstage becomes the platea that is ideal for intimate and close communications with the audience via soliloquies, asides and stichomythia. Upstage on The Globe stage, the locus, offers the more formal space for King’s addresses etc. Actors at The New Globe have found the extreme edges outside the pillars provide the most powerful positions to play - the ‘hotspots’ for interacting with the audience. Thus Shakespeare blocks the scene in the writing of it and this was read by players at The Globe. The words define the space from which they are shared. Three-dimensional performances The Globe stage offered more than a thrust stage, indeed almost theatre in the round with the Lord’s Room behind the players next to the balcony. This obviously had profound implications because acting became virtually three-dimensional. There is no front and back in a circle and certainly no room for stasis. Almost continuous movement was required on the stage, as performers kept moving for the sake of their audience. Diagonal blocking was required using the depth as well as the breadth of the stage. The impulse of the modern actor is to move forwards to the front of the stage. Directors at The New Globe have thus resorted to using ‘imaginary ropes’ in rehearsals to try to pull actors towards the diagonal lines. The actor is a storyteller surrounded by an intimate circle of ‘listening ears’, rather than an actor framed inside a proscenium-arch stage being ‘viewed’ by a grey outline of spectators. Rylance stated that: It (performing at The Globe) was closer to pure storytelling … The audience weren’t to be ignored.13 5 PREMIER’S TEACHER SCHOLARSHIPS The timing of plays As Kermode states, the plays at The Globe must have been shorter than many productions of Shakespeare today.14 While, as stated, there was no intermission, two hours would probably have had to be the maximum duration of performances particularly during colder days when the dark descended at 4 p.m. because the theatre had no lighting. While we reject the ‘bad’ Quarto of 1603 for the exclusions and cuts, its existence further highlights that Shakespeare’s plays did exist in different forms and were most probably cut and patched, particularly for provincial touring and for time reasons, particularly for winter months. Once again, the audience was to be served. Illusion Since no gulf existed between actor and audience, there was no stage realism in the sense that we know it. The actor had to find a balance so that they did not completely step outside the fiction offered by the play. Rather than assume the position of voyeur, the audience were part of the action and seem to have been able to suspend disbelief to an extent and become involved with the action. The Shakespearean audience had a sense that fiction is used to explore realities, not imitate reality, and Hamlet knew this well, hence his use of theatre, the play within the play, to ‘catch the conscience of the King’. Records do confirm that audiences were involved and showed emotions freely. Shakespeare in Love, the film, delightfully captures this audience appeal. Speaking the script If, as discussed, people came to listen rather than to watch Shakespeare’s plays, rhetorical skills rather than acting as we know it would have been emphasised and appreciated. Many players would have thus employed direct speech in performance, directly communicating with the audience. The acting that took place, however, was not pantomime as some critics might imply. Links with Commedia dell’Arte are obvious in conventional physicality and in the audience participation in moulding the theatrical experience. Perhaps we need a new term to describe this shared space of fictional and theatre worlds. Never would the audience have stood back reverently applauding the now so-called sacred works of Shakespeare—the play ‘sank or swam’ based on audience interest. Realism at the Globe, then, was a far cry from the kind of realism we expect in modern plays. It is a testament to the genius of Shakespeare, however, that his plays can be performed in almost any acting style and still have something to say to an audience. Music and dance The New Globe experience has demonstrated that when there is no stage design in terms of set, controlled lighting and elaborate properties, music becomes much more important in the creation of mood and meaning, a more truly expressive form through necessity. Claire van Kampden, a contemporary music director, has stated of her experience at The New Globe: Music has to be very specific to what is going on stage … (since) the economy of sound draws the audience into the story.15 Performances probably started with music while the seats were filling. Plays, whether comedy or tragedy, ended with jigs, however incongruous that might seem for today’s audiences. The Elizabethan actors Will Kemp and Richard Tarlton were famous as dancers. An Elizabethan eyewitness, Platter, tells us that at the end of Julius Caesar the actors danced ‘exceedingly gracefully’. Elizabethan actors must have been extremely versatile—as tumblers, dancers and swordsmen as well as master rhetoricians. While we may witness the tradition of end-ofperformance jigs (and within performances for The New Globe’s 2004 production of Measure for Measure), this is a tradition and practice that has been lost. Certainly the jig for Elizabethan audiences would have brought the play back to fiction, debriefed them if you like. It also seems to have been a tradition for males to remove headdress in the jig while still in Elizabethan 6 PREMIER’S TEACHER SCHOLARSHIPS women’s dress, further evidence of the jig acting as a debriefing session while also offering valuefor-money entertainment. Costumes A major source of stage symbolism, costumes offered crucial signifiers of meaning that reinforced the dialogue. They signified not only a particular role but also social status. High hats, for example, signalled high status, the monarch figure upon the stage always wearing the highest hat. Costumes also helped to establish settings. Nightcaps, for example, quite obviously signalled night. In a time of little scenery and often just a bare platform, the relationships between and identification of characters could rest solely with dress. Thus Viola and Sebestian in Twelfth Night were made identical twins not by their faces but by their similar dress. This was also the Age of Procession as Elizabeth’s costumed Coronation Progress in 1559 indicated. Colour of costume was particularly significant. Hamlet’s black and Malvolio’s yellow garters stood out immediately for the Elizabethan audience as discordant elements in a tradition of dress that everyone knew in detail. Thus colour was an instrument of meaning as well as offering the spectacle. Perhaps even more so than today, the dramaturgical possibilities of costumes could be exploited in terms of characterisation and social hierarchy, particularly in terms of ironic potential. It would also seem though that actors mixed their own clothes and costumes. If an actor was to dress as a Roman, for instance, we have drawings that tell us that the toga would be draped over contemporary fashions, with no real attempt to disguise the undergarments or to offer the degree of realism that we would expect. Conclusions and implications for teaching Shakespeare in performance As stressed by Brown in sharing the experience of Shakespeare’s scripts with students, we need to focus on these scripts as they become part of a theatrical event.16 Going back to Kinney’s words: In ‘reading’ Shakespeare this way we become collaborators with the playwright, too, just as his actors were.17 By appreciating Shakespearean scripts as blueprints for performance at The Globe, students may hopefully appreciate that the works of the Bard belong to the people. Pretensions may be stripped away and students should thus not fear playing with what have since been deemed canonical texts. The Globe playhouse occupies a special place in the collective consciousness of Shakespearean studies and The New Globe reconstruction has brought important theoretical and practical conflicts into the open. It was in 1642 that Parliament closed the theatres in London and they stayed closed until the Restoration, when they returned in a very altered form. The history of Shakespeare and his company, indeed the great age of English drama, need not end here, however. As Germaine Greer states: Shakespeare developed a theatre of dialectical conflict, in which idea is pitted against idea and from their deeper friction a deeper understanding of the issues emerges.18 Ultimately Shakespeare entertained the masses but he also raised a myriad of interesting ideas. Hopefully students will gain from their study of Shakespeare and his plays a ‘deeper understanding’ of both themselves and the world in which they live. The more willing we are to ‘strip the Bard bare’, the closer we may approach the works of the Bard and thus make them our own. 7 PREMIER’S TEACHER SCHOLARSHIPS Endnotes 1. A term denoting worshippers of the Bard as cited by Groom and Piero, Introducing Shakespeare, Icon Books UK, 2001, p. 4. 2. F Kermode, Age of Shakespeare, Weidenfeld and Nicholson, 2004, p. 64. 3. P Kiernan, Staging Shakespeare at the New Globe, Palgrave, 1999, p. 8. 4. Cited in A Gurr, Shakespearean stage, 3rd edn, Cambridge, 2003, p. 6. 5. AF Kinney, Shakespeare by stages, Blackwell Publishing, 2003, p. 32. 6. AF Cited in Kinney, Shakespeare by stages, Blackwell Publishing, 2003, p. xii. 7. P Kiernan, Staging Shakespeare at the New Globe, Palgrave, 1999, p. 3. 8. P Kiernan, op cit., p. 5. 9. Golmman cited in P Kiernan, p. 37 10. P Kiernan, p. 37. 11. AF Kinney, op cit, p. 12. 12. AF Kinney, p. 13. 13. P Kiernan, op cit, p. 28. 14. F Kermode, op cit, p. 119. 15. Cited in P Kiernan, op cit, p. 86. 16. JB Brown, Shakespeare and the theatrical event, Palgrave, 2002, p. 4. 17. AF Kinney, op cit, p. 32. 18. G Greer, Shakespeare, a very short introduction, Oxford, 2002. Bibliography Brown, JB, Shakespeare and the theatrical event, Palgrave, 2002. Greer, G, Shakespeare, a very short introduction, Oxford, 2002. Groom and Piero, Introducing Shakespeare, Icon Books UK, 2001. Gurr, A, Shakespearean stage, Third Edition, Cambridge, 2003. Herford, R, ‘Little did I imagine’, in The Woman in Black Theatre Program, 2004. http://www.bardweb.net/words.html Jones, J., Southwark: A history of Bankside, Bermondsey and ‘The Borough’, Robert J Godley Publishers, 1996. Kermode, F, Age of Shakespeare, Weidenfeld and Nicholson, 2004. Kiernan, P, Staging Shakespeare at the New Globe, Palgrave, 1999. Kinney, AF, Shakespeare by stages, Blackwell Publishing, 2003. Laroque, F, Shakespeare: Court, crowd and playhouse, Thames and Hudson, 2002. 8 PREMIER’S TEACHER SCHOLARSHIPS 9