* Your assessment is very important for improving the work of artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download Malaria and the human genome

Survey

Document related concepts

Transcript

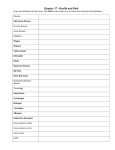

STUDENT’S GUIDE Case Study Malaria and the human genome Steve Cross, Bronwyn Terrill and colleagues Wellcome Trust Sanger Institute Hinxton Version 1.1 Case Stu Case Stud malaria and the human genome Malaria and the human genome IMAGE FROM: Wellcome Images. Each year, the malaria parasite Plasmodium falciparum kills over a million African children and causes debilitating illness in over half a billion people worldwide. Malaria is the strongest known selective force in the recent history of the human genome. Many types of genetic variation have evolved in humans due to selection by the malarial parasite, causing variation in red blood cell regulation, structure and antigen expression. In this activity, you will investigate the origin and action of mutations that are thought to have arisen in human populations in response to selection pressure from malaria. Activity overview Malaria is a debilitating illness that affects more than 40% of the world’s population caused by parasites of the genus Plasmodium. This disease is thought to be the strongest selective force on our species’ in recent history. Researchers believe that this is responsible for the diverse range of genetic adaptations that protect against malaria in different populations’ genomes. In this activity, you will use a common statistical test (chi-squared) to work out whether a genetic mutation is associated with incidence of the disease, or whether the two events are independent. What is malaria? Every year, malaria causes hundreds of millions of people to be ill and kills between one and three million, most of them children in sub-Saharan Africa. It is a disease caused by a protozoan parasite that is spread by mosquitoes and which multiplies inside human blood cells. It causes fevers, chills and shortness of breath (the symptoms are like severe flu) and, in extreme cases, coma and death. Malaria is a disease that is older than humans, and there are malarial parasites that infect birds, lizards and primates other than humans. The human form of malaria seems to have existed for at least 100,000 years, although it probably only became such a vicious killer about 10,000 years ago. Malaria is currently found in a band that extends across the tropics, throughout Africa, southern Asia, Central America and the north of South America. At one time, it also extended north into Europe and North America. Copyright © Steve Cross, Bronwyn Terrill et al 2011 2 www.dnadarwin.org malaria and the human genome Malaria can be treated with a wide variety of drugs, from the threehundred-year-old quinine to recently-developed treatments. The choice of drug depends on the type of malaria infection and the development of resistance to drugs by some strains in some areas. There is currently no vaccine for malaria, but there is a huge international effort to develop one. Malaria is the focus of a large amount of medical research, and the genome of the most common forms of the disease was sequenced in 2002 by staff at the Wellcome Trust Sanger Institute. How malaria is caused Malaria is caused by a group of protozoan parasites of the genus Plasmodium. There are four types of Plasmodium. P. falciparum is the most common form on the African continent and causes the most severe malaria of any type. P. vivax is the form of the infection most often seen in Asia. The other two species, P. ovale and P. malariae, are less common. Malaria life cycle The malaria parasites are spread by female Anopheles mosquitoes, being injected into the human bloodstream when the mosquito sucks blood (1). Once in the blood vessels (2), the parasites (known as sporozoites) migrate to the liver (3), where they can multiply, safe from attack by the immune system. The next stage in the parasite’s life cycle is to invade red blood cells (4). In the red blood cells, the malarial parasites of this stage (merozoites) can multiply to huge numbers before bursting the cells and re-entering the bloodstream (5a). Alternatively, they can invade red blood cells to turn into sex cells known as gametocytes (5b). Gametocytes can be taken up by mosquitoes through the same biting process and blood meal as before. In the mosquito’s intestine, the sex cells mate; their offspring can then migrate to the mosquito salivary glands ready to be passed into a new human host. Copyright © Steve Cross, Bronwyn Terrill et al 2011 3 www.dnadarwin.org malaria and the human genome Malaria as a selective pressure on humans Researchers believe that there is evidence in the human genome that malaria has been the single greatest selective pressure on human beings in recent genetic history. Because it is so widespread, and so deadly, malaria has killed huge numbers of humans, and our genomes bear scars of a long ‘arms race’ with this disease. There are numerous specific genetic variations which are found most often in areas where malaria is common, some of which have been shown to offer protection against infection. One of these genetic variants might explain why P. vivax is so rare in Africa compared to P. falciparum. In western and central Africa most people have genetic variants that mean that they do not produce a specific protein, called the Duffy protein, on the surface of their red blood cells. This protein is used by P. vivax as a way to enter red blood cells, and thus these people are immune to P. vivax. This suggests that there has been very high exposure to P. vivax in these regions in the past few thousand years, but that human DNA changes have meant that this particular parasite is much rarer now. Sickle cell trait and sickle cell anaemia Sickle cell anaemia is a genetic condition that is found mainly in areas where malaria in endemic. The mutation that causes sickle cell anaemia is commonly said to be recessive, in that only people with two copies of the disorder form of the gene are affected by the full disease. In fact, even carriers with one copy of the gene, who are said to have ‘sickle cell trait’, will have a small percentage of sickled cells in their blood. At a molecular level, they also have a significant change in half of their haemoglobin molecules. The molecular structure of haemoglobin. The two beta subunits are in blue. Copyright © Steve Cross, Bronwyn Terrill et al 2011 4 www.dnadarwin.org malaria and the human genome A change of a single nucleotide in the HBB gene, β-globin (on chromosome 11), causes sickle cell trait, and having this change on both copies of chromosome 11 causes sickle cell anaemia. β-globin is one of the proteins that makes up haemoglobin — a complex found in red blood cells that binds oxygen for transport around the body. The allele with this change is often called Hbs for short, with the non-sickle cell version being known as Hba. The unaffected genotype is therefore written Hba Hba , the sickle cell trait genotype is Hba Hbs and the sickle cell anaemia genotype is Hbs Hbs . PHOTO BY: E.M. Unit, Royal Free Hospital School of Medicine/Wellcome Images. The symptoms of the disorder are visible at a microscopic level. The red blood cells of a homozygote for the sickle cell allele tend to adopt a rigid sickle shape. This means that they cannot move as freely through small blood vessels, and therefore cannot transfer oxygen as effectively to some organs. Symptoms include organ pain and fever, and often occur in bouts rather than being continuous. People with sickle cell anaemia usually have a shortened life span. Sickle and normal red blood cells. People with one copy of the sickle cell allele and one standard allele only tend to feel sickle cell symptoms under extreme conditions of oxygen deprivation, such as climbing a mountain, or if seriously dehydrated. Because the sickle-cell mutation only alters a single base in the DNA sequence, it is known as a single-nucleotide polymorphism, or SNP (pronounced ‘snip’). Internationally, researchers focus on the role that SNPs play in human disease. SNPs have been found that offer some protection against obesity, heart disease and diabetes. In malarial regions of Africa, about 1 in 10 people carries at least one sickle cell allele. Copyright © Steve Cross, Bronwyn Terrill et al 2011 5 www.dnadarwin.org malaria and the human genome Is sickle cell trait or anaemia associated with malaria? Sickle cell anaemia is, at first glance, a paradox. If possessing two copies of an allele causes such serious disorder, and historically would have caused death before reproductive age, how can that allele be so common? A clue to the reasons can be found by looking at the distribution of the sickle cell allele on a world map, and comparing it to the distribution of P. falciparum; Both are found in the same regions. This would suggest that maybe the sickle cell allele is protecting some people against malaria, even as it has adverse effects on others. Number of cases of malaria 1 million or more 1 million — 500, 000 500, 000 — 100, 000 100, 000 — 10, 000 10, 000 — 1, 000 Fewer than 1, 000 A map of the distribution of malaria in populations of Africa and South Asia. The darker the green, the greater the incidence of the disease. Data source: World Health Organisation. % of population with Hbs 14 + 12 — 14 10 — 12 8 — 10 6—8 4—6 A map of the distribution of the sickle cell allele in populations of Africa and South Asia. Copyright © Steve Cross, Bronwyn Terrill et al 2011 6 www.dnadarwin.org malaria and the human genome The key to this protection is that carriers of only one copy of the sickle cell allele, who also have one healthy allele, do not suffer from the anaemia, but are protected against malaria by their sickle cell trait. This is often quoted as an example of a phenomenon known as heterozygote advantage. In this instance, because the heterozygote is fitter (in an evolutionary sense) than either of the homozygotes in a specific set of circumstances, there will always be a balance of genes in the population, rather than one form being fixed by selective pressure. Where there is little malaria, the superior fitness of the non-sickle form drives this variant to fixation. Exercise 1 Exploring the effects of sickled cells To understand the effect of the SNP that causes sickle cell trait and sickle cell anaemia, you will first need to characterise it. You will be using JavaScript DNA Translator 1.1, a simple tool for analysing DNA sequences. The first 60 nucleotides of the normal form of the gene look like this: ATG GTG CAT CTG ACT CCT GAG GAG AAG TCT GCC GTT ACT GCC CTG TGG GGC AAG GTG AAC The mutated (sickle cell) form looks like this: ATG GTG CAT CTG ACT CCT GTG GAG AAG TCT GCC GTT ACT GCC CTG TGG GGC AAG GTG AAC Open the file JVTtranslator.shtml with a web browser (it looks best in Mozilla Firefox). You will be presented with this screen: Give your sequence a name here. Paste the DNA sequence here. Ensure that the 'Reading frame' is set to '1' so that the software starts at the beginning of the sequence. Click 'Translate'. Copyright © Steve Cross, Bronwyn Terrill et al 2011 7 www.dnadarwin.org malaria and the human genome Type a name for your sequence into the top box (‘standard’ or ‘sickle’ for example). Cut and paste one of the DNA sequences from the text file called DNA_sequences.txt into the second box. You’ll need to tell the software that you’re only interested in one protein sequence from this DNA, by changing Reading Frame to 1. Now click the Translate button. The screen that is generated will give you your results. The easiest version of the protein sequence to read is in the yellow box. Here is a list of what the letter codes in the yellow box represent in terms of the amino acids in the predicted protein. Asp Glu Arg Lys His Asn Gln Ser Thr Tyr D Aspartic acid E Glutamic acid RArginine KLysine HHistidine NAsparagine QGlutamine SSerine TThreonine YTyrosine Ala AAlanine Gly GGlycine Val VValine Leu LLeucine IleIIsoleucine Pro PProline Phe FPhenylalanine Met MMethionine Trp WTryptophan Cys CCysteine Amino acid codes The three-letter and single letter codes for the 20 amino acids that are found in proteins. Most computer software uses the single-letter codes to show the different amino acids. An example of output from the JaveScript Translator. The amino acid sequence is in the yellow box. Questions a. What has changed in the sickle cell gene? b. What has changed in the sickle cell protein? Copyright © Steve Cross, Bronwyn Terrill et al 2011 8 www.dnadarwin.org malaria and the human genome Exercise 2 Does sickle cell protect against malaria? In this exercise you will test the hypothesis that the sickle cell allele is associated with protection against malaria. Rather than look at the geographical distribution of the parasite and the gene, you will be looking directly at the life histories of people with and without the sickle cell SNP, and comparing their chances of infection. When trying to demonstrate a relationship or association between a genetic change and a disease, it is important to gather data in different ways and from different sources, to prevent yourself from coming to inaccurate conclusions about a gene’s importance. There are many studies that claim to have found a correlation between a specific genetic change and a disease or susceptibility, without any idea of how this might happen. Only by repeating studies and looking for mechanisms by which the disease is caused can scientists be sure that associations are real rather than just statistical anomalies. The data You are going to analyse real data from a 2008 study to evaluate the evidence that the sickle cell allele is associated with malarial incidence. The hypothesis is that people with sickle cell trait will be less likely to become hospitalised with malaria. Every year millions of children worldwide are hospitalised with severe malaria. For this study, DNA was taken from 500 children attending a single hospital. The DNA was examined, and the sickle cell SNP status was determined for each child. As the control sample, DNA was also taken from 500 people in the population near the hospital. These were people who had not been admitted to hospital with severe malaria as children. The sickle cell SNP status was also determined for each person in this population. You will need to perform a statistical test to find out whether the prevalence of the sickle cell allele is significantly greater in the general population than in children being admitted to hospital with severe malaria. This test evaluates whether the variation in numbers is a result of chance or a real effect. You will be looking at individual chromosomes rather than people. This is because the paired chromosomes of humans would make the test much more complicated than it would be if you were to use individual chromosomes. Copyright © Steve Cross, Bronwyn Terrill et al 2011 9 www.dnadarwin.org malaria and the human genome The Chi-Squared test The Chi-Squared test can be used here to test the following null hypothesis. Null hypothesis: There is no difference in the prevalence of the sickle cell allele in the chromosomes of people with and without malaria. Alternative hypothesis: There is a significant difference in the prevalence of the sickle cell allele in these populations. Open the Excel spreadsheet called malaria_data_student. There are two worksheets: Cases and Controls. (Your teacher may also give you another worksheet called Student Table to use.) On the Cases and Controls worksheets, there are 500 people’s genotypes at specific locations in the genome. Remember the Cases were from people in hospital with malaria; Controls were from people in the community. The column you’re interested in is Column E: HbS. Sort the data and count the rows to work out how many As and Ts have been observed in the different populations. Fill in the table below using the chromosome data you have been given: Category Observed (O) Expected* (E) (see below) O–E (O–E)2 (O–E)2 E Has malaria Has Hbs (T) Has malaria No Hbs (A) No malaria Has Hbs (T) No malaria No Hbs (A) TOTALS * To calculate the Expected values, you will need to count the number of Hbs alleles found across the entire population under test (1,000 people and therefore 2,000 chromosomes). This figure, divided by the total chromosome population size (2,000) will give you the prevalence of the Hbs allele. Multiplying the prevalence of each form of the allele by the number of people’s chromosomes in each test group, will give you the Expected values. Copyright © Steve Cross, Bronwyn Terrill et al 2011 10 www.dnadarwin.org malaria and the human genome Size of population (ignoring alleles) Category Prevalence of allele Expected Has Hbs No Hbs (O–E)2 The total of E across all four groups is the chi-squared value ( χ 2). There is only one degree of freedom in this experiment. Using this information, calculate the probability of the null hypothesis being true using this lookup table, where p is the probability. p 0.25 0.2 0.15 0.1 0.05 0.025 0.01 0.005 0.001 0.0005 χ 2 1.32 1.64 2.07 2.71 3.84 5.02 6.63 7.88 10.83 12.12 Questions c. What is the probability that the null hypothesis is true? d. Does this mean that the result is statistically significant? e. Does this information reinforce or contradict the data based on mapping the prevalence of malaria and the sickle cell allele published above? Copyright © Steve Cross, Bronwyn Terrill et al 2011 11 www.dnadarwin.org