* Your assessment is very important for improving the work of artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download Optimal Loading of Audio Transformers for Crystal Set Use

Chirp spectrum wikipedia , lookup

Opto-isolator wikipedia , lookup

Electric power system wikipedia , lookup

Transmission line loudspeaker wikipedia , lookup

Electrification wikipedia , lookup

Loudspeaker wikipedia , lookup

Skin effect wikipedia , lookup

Power inverter wikipedia , lookup

Voltage optimisation wikipedia , lookup

Variable-frequency drive wikipedia , lookup

Mathematics of radio engineering wikipedia , lookup

Pulse-width modulation wikipedia , lookup

Power engineering wikipedia , lookup

History of electric power transmission wikipedia , lookup

Nominal impedance wikipedia , lookup

Magnetic core wikipedia , lookup

Mains electricity wikipedia , lookup

Zobel network wikipedia , lookup

Audio power wikipedia , lookup

Resistive opto-isolator wikipedia , lookup

Three-phase electric power wikipedia , lookup

Electrostatic loudspeaker wikipedia , lookup

Buck converter wikipedia , lookup

Distribution management system wikipedia , lookup

Switched-mode power supply wikipedia , lookup

Utility frequency wikipedia , lookup

Resonant inductive coupling wikipedia , lookup

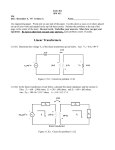

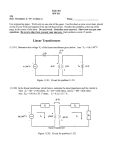

Optimal Loading of Audio Transformers for Crystal Set Use Crystal receivers have attracted for decades the attention of radio enthusiasts, mainly because of its low parts count and capability for long-distance reception when connected to an efficient antenna-ground system. Overall crystal set design (and construction) criteria try to get the most of the RF power intercepted by the antenna into the headphones, ultimately as audio-frequency power, this power being converted into sound by the hearing element. In recent years, utmost importance has been given to the utilization of matching audio transformers and suitable hearing devices for ultimate volume improvements in these receivers. Fig.1 shows the schematic diagram of a basic crystal set featuring an audio impedance-matching stage. This article will present technical material the author believes could be helpful to the hobbyist when selecting a suitable audio transformer for his set or when studying utilization of the one just found in the spare parts box. We shall begin making some basic power calculations. First, consider a sine-wave generator delivering power to a resistive load RL, as shown in Fig.2. Vg is the peak amplitude of the source voltage and Rg is the source resistance. The average power dissipated by RL is: 2 PL VL 2 RL …(1) where VL is the peak value of the voltage across the load. VL is computed as: RL VL V g RL R g Substitution into eq.(1) yields: PL V g 2 RL 2RL R g 2 Maximum power is delivered to the load when RL = Rg. In this particular case: PL PL MAX Vg 2 8Rg …(2) This is the maximum available power. Next, consider the situation where RL differs from Rg and we still want the maximum available power delivered to RL. At audio frequencies, it is common practice to connect a matching transformer between the source and the load. This device permits transformation of impedance levels, such that the generator “sees” an equivalent load RL’ = Rg. Maximum power is then available and it will be transferred to R L. Please refer to Fig.3. The transformer should be a low-loss type, in order to restrict power losses to a minimum. Usually, a specially treated steel-laminated core is used when higher permeability values and very tight magnetic coupling between windings is required. In a crystal receiver, Rg represents the detector diode’s output resistance at audio frequencies and RL, the effective average impedance of a pair of 2k ohms DC resistance magnetic headphones, sound powered headphones or piezoelectric ceramic or crystal earpiece. RL must be matched to Rg for maximum power transfer to the hearing device. Modeling a transformer An equivalent network for an audio transformer can be seen in Fig.4. Here, circuit parameters have been defined in terms of the inductances LP and LS of the primary and secondary windings, the coupling coefficient k between these windings, stray capacitances and losses. The following relationships apply: Lm k 2 L p L1 1 k 2 L p …(3.1) …(3.2) N k Lp Ls …(3.3) Lm is the magnetizing (or shunt) inductance. Its finite value is responsible for power losses at low audio frequencies. L1 is the equivalent leakage inductance referred to the primary side. It results from magnetic flux not mutually linked by the windings and contributes to losses at high frequencies. N is the “turns ratio”. The copper loss (resistance) of the primary and secondary windings is represented by Rp and Rs, respectively. Rc represents core losses. Contributions to these losses come from eddy-currents and hysteresis behaviour. C1 and C2 are the intra-winding capacitances and Cc is the inter-winding capacitance. These three are stray (parasitic) capacitances. They also contribute to power losses at the high-frequency end of the response. If the windings are DC-isolated from each other, the short connecting the lower ends of the ideal transformer in the model should be substituted by a second capacitor Cc connected between the lower input and output terminals. Selecting a suitable transformer For crystal set use, a good transformer should have a flat response from 300Hz to 3000Hz (or better) when loaded following manufacturer´s specs. Accordingly, the following relationships should be satisfied: Rg R p RL Rs …(4) Rc RL Rg ' k 1 Also, at rated loads, the effects of C1, C2 and Cc should be noticeable only at higher frequencies, beyond the midband. A typical amplitude versus frequency response curve for an audio transformer is shown in Fig.5. In this figure, 0dB refers to the output level at midband frequencies. At frequencies fL and fH the output is down by 3dB. For a load resistance RL equal to or greater than the rated value RL nominal , but much smaller than Rc/N2, the transformer may be represented by the simplified models of Fig.6. We are interested in knowing if a specific transformer will efficiently match the given impedance levels Rg and RL. We would also like to know if the 300Hz~3000Hz bandwidth (minimum) will be accomplished by using this audio transformer. If the device has been manufactured for audio frequency operation (there are reports saying that small 60Hz low-voltage power-line transformers have been successfully used as matching devices), then chances are that it will reproduce frequencies up to at least 3000Hz. However, attenuation at lower frequencies will be strongly dependent on the magnetizing inductance Lm and the value of the source resistance Rg (high-quality units may reproduce frequencies down to 50Hz +/-1dB, referenced to the midband). The equivalent circuit shown in Fig.6.c is very valuable for evaluating transformer operation at frequencies below the midband. We will use this model for calculation of fL, the lower -3dB frequency (please see Fig.5). At this frequency, the power delivered to the load RL will be one half of that available in the midband, this is, it will be 3dB down. Computing the half-power point If we lower the operating frequency, eventually the primary’s magnetizing inductance Lm will start shunting the available signal, reducing the output power. Recalling that at mid frequencies Vp = Vg/2, the half-power point of the response will be described by that frequency at which the amplitude of the primary’s voltage falls to: Vp Vg …(5) 2 2 With Fig.6.c in mind, we may draw the circuit of Fig.7 to help us in the calculation of the lower -3dB frequency. Analysis of the circuit yields for the primary’s voltage: Vp Vg 2 jLm Rg 2 jLm where = 2f is the radian frequency and j 1 . Then, for the half-power point [eq.(5)]: Vg 2 2 Vg 2 Lm Rg 2 2 Lm 4 2 or: 2 Lm 1 2 Rg 2 2 2 Lm 4 2 Simplifying: Rg 2 Lm …(6) The above equation tells us that, under matched conditions, at the lower –3dB frequency the reactance of the magnetizing inductance equals one half of the source resistance. Then: 3dB Rg 2 Lm and: f 3dB 1 Rg 2 2 Lm …(7) If the shunt inductance Lm and the source resistance Rg are known quantities, f3dB can be readily obtained. On the other hand, if Lm and the turns ratio N are known, selecting f3dB will yield the corresponding values for Rg and the optimum load RL, recalling that Rg = N2RL. A useful approximation for N is: N Lp Ls …(8) which requires that LP and LS be known. Also, being k 1, we may write Lm LP. Working out some examples Case # 1 Some months back the author received a small audio transformer having the code ST-11 stamped on its side. No technical info was available at that time. The only known fact was that the external connection to the windings was a set of flexible green, red, white and black wires. With the help of an audio generator and an oscilloscope some basic measurements were made. First, the green-red wires were identified as corresponding to the high-impedance winding (primary) and the white-black pair as that pertaining to the low-impedance side (secondary). Then, an approximate value for the turns ratio N was obtained. A 0.1V peak-amplitude 1kHz signal was applied to the primary, giving 0.022V peak across the unloaded secondary. This yielded a 4.54:1 voltage transformation ratio or N. However, it is recommended the turns ratio be measured under rated-load conditions (impractical at this point of our work, as we knew nothing about the impedances of this little transformer). The author could also get a hand on a B&K 875A LCR meter for inductance and resistance measurements. The high-impedance winding measured LP = 19.5H and DC resistive losses of Rp = 1.236k ohms. The low-impedance side showed LS = 0.833H and DC resistive losses of Rs = 153 ohms. Applying eq.(8) a value of 4.84 for N was obtained. This value is believed to be a better approximation for N. As mentioned before, the minimum acceptable bandwidth should be 300Hz to 3000Hz, flat. In practice, amplitude response variations of +/-1dB relative to the midband are acceptable. For the response at 300Hz to be within this tolerance, we must select 150Hz as the –3dB frequency (at two times the corner frequency, the response is within 1dB of the value found at mid frequencies). From eq.(7) we already know that at f3dB the primary’s reactance equals Rg/2. At two times f3dB, the reactance will equal Rg. This is a useful result, stating that at the lower end of the flat passband the primary’s reactance will be equal to Rg. We can use the above results in the following way. From the formula for a coil’s reactance: X L 2fL …(9) the impedance of the primary winding at 300Hz (neglecting resistive losses) is found to be Xp = 36.757k ohms. The secondary winding yields a value Xs = 1.57k ohms. Accordingly, Rg should be 36.757k ohms for a –3dB frequency of 150Hz, the optimum load being RL = 1.57k ohms. A hearing device having an effective average audio impedance around 1.5k ohms will be matched to a detector diode’s output audio impedance of 30…..40k ohms. This is likely a value for a typical germanium 1N34 diode in an average performance crystal set using a tapped detector coil. If higher load impedances are used, the –3dB frequency will be shifted upwards and there will be losses at bass frequencies. For core losses to be neglected, the transformed load impedance should satisfy the following relationship: RL N 2 RL ' Lp Ls RL Xp Xs RL Rc In the present case, Rc was found to be 447k ohms (the method for taking this measurement will be discussed in a future article). As a gross approximation, a value for Rc equal to 20 times N2RL nominal may be assumed for a good audio transformer. Accordingly, the optimum values for Rg and RL should be: Rg 447 22.35kohms 20 RL 22.35 XS 0.954kohms XP Technical data was found recently on this transformer describing it as a Philmore 20k:1k 50mw input transformer (no more info available). Case #2 Our second real-world example deals with the Calrad 45-700 audio transformer, specified by the manufacturer as a 100k:1k matching device. Measurements were taken to verify technical data found on the Internet. Results are tabulated below. Winding Primary Secondary Wire Color Code Green-Red Green-White Inductance Lp = 52.5H Ls = 0.55H Copper Losses Rp = 2.11k ohms Rs = 69.6 ohms Calculated reactances at 300Hz are Xp = 98.96k ohms and Xs = 1.036k ohms for the primary and secondary, respectively, very close to the rated transformed and load impedances (100k ohms and 1k ohms). The above values suggest that, under rated loading and matched conditions, the Calrad 45-700 will yield a lower corner frequency approximately equal to 150Hz. Acknowledgements The author would like to express here his gratefulness to Steven Coles, Gil Stacy, Ben Tongue and Dave Schmarder for their most kind technical support and encouragement. Ramon Vargas Patron [email protected] Lima-Peru, South America March 8th, 2005