* Your assessment is very important for improving the workof artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download File - Myers English

Regions of ancient Greece wikipedia , lookup

Ancient Greek architecture wikipedia , lookup

Greek contributions to Islamic world wikipedia , lookup

History of science in classical antiquity wikipedia , lookup

Ancient Greek warfare wikipedia , lookup

Ancient Greek grammar wikipedia , lookup

Ancient Greek medicine wikipedia , lookup

Economic history of Greece and the Greek world wikipedia , lookup

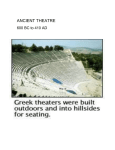

Greek Revival architecture wikipedia , lookup

Greek Theater Mini Research Sophocles - Notes could include. . . 1._______________________________________________ Who he is 2._______________________________________________ His achievements 3._______________________________________________ How he changed theater The Theater Set Up - Notes could include. . . 1._________________________________________________ Parts of the stage 2._________________________________________________ Seating 3._________________________________________________ Sound Festival of Dionysus Notes could include. . . - How it started - How it changed - What happened there The Actors Notes could include. . . - 1._________________________________________________ 2._________________________________________________ 3.__________________________________________________ 1.__________________________________________________ How many 2.__________________________________________________ Who they were 3.___________________________________________________ The Chorus Costumes / Props / Sets Notes could include. . . 1.____________________________________________________ What they wore 2.____________________________________________________ Props 3.____________________________________________________ - Masks Sophocles A marble relief of a poet, perhaps Sophocles. Sophocles was born about 496 BC in Colonus Hippius (now part of Athens). He was to become one of the great playwrights of the golden age. The son of a wealthy merchant, he would enjoy all the comforts of a thriving Greek empire. Sophocles was provided with the best traditional aristocratic education. He studied all of the arts. By the age of sixteen, he was already known for his beauty and grace and was chosen to lead a choir of boys at a celebration of the victory of Salamis in 480 BC. In 468 BC, at the age of 28, he defeated Aeschylus, whose pre-eminence as a tragic poet had long been undisputed, in a dramatic competition. In 441 BC he was in turn defeated in one of the annual Athenian dramatic competitions by Euripides. From 468 BC, however, Sophocles won first prize about 20 times and many second prizes. His life, which ended in 406 BC at about the age of 90, coincided with the period of Athenian greatness. He was not politically active or militarily inclined, but the Athenians twice elected him to high military office. Sophocles wrote more than 100 plays of which seven complete tragedies and fragments of 80 or 90 others are preserved. He was the first to add a third actor. He also abolished the trilogic form. Sophocles chose to make each tragedy a complete entity in itself--as a result, he had to pack all of his action into the shorter form, and this clearly offered greater dramatic possibilities. Sophocles also effected a transformation in the spirit and significance of a tragedy; thereafter, although religion and morality were still major dramatic themes, the plights, decisions and fates of individuals became the chief interest of Greek tragedy. “Sophocles.” Ancient Greece. University Press, Inc. 2003-2012. Web. 22 September 2013. <http://www.ancientgreece.com/s/People/Sophocles/>. Sophocles, (born c. 496 bc, Colonus, near Athens [Greece]—died 406, Athens), with Aeschylus and Euripides, one of classical Athens’ three great tragic playwrights. The best known of his 123 dramas is Oedipus the King. Life and career Sophocles was the younger contemporary of Aeschylus and the older contemporary of Euripides. He was born at Colonus, a village outside the walls of Athens, where his father, Sophillus, was a wealthy manufacturer of armor. Sophocles himself received a good education. Because of his beauty of physique, his athletic prowess, and his skill in music, he was chosen in 480, when he was 16, to lead the paean (choral chant to a god) celebrating the decisive Greek sea victory over the Persians at the Battle of Salamis. The relatively meager information about Sophocles’ civic life suggests that he was a popular favorite who participated actively in his community and exercised outstanding artistic talents. In 442 he served as one of the treasurers responsible for receiving and managing tribute money from Athens’ subject-allies in the Delian League. In 440 he was elected one of the 10 stratēgoi (high executive officials who commanded the armed forces) as a junior colleague of Pericles. Sophocles later served as stratēgos perhaps twice again. In 413, then aged about 83, Sophocles was a proboulos, one of 10 advisory commissioners who were granted special powers and were entrusted with organizing Athens’ financial and domestic recovery after its terrible defeat at Syracuse in Sicily. Sophocles’ last recorded act was to lead a chorus in public mourning for his deceased rival, Euripides, before the festival of 406. He died that same year. These few facts are about all that is known of Sophocles’ life. They imply steady and distinguished attachment to Athens, its government, religion, and social forms. Sophocles was wealthy from birth, highly educated, noted for his grace and charm, on easy terms with the leading families, a personal friend of prominent statesmen, and in many ways fortunate to have died before the final surrender of Athens to Sparta in 404. In one of his last plays, Oedipus at Colonus, he still affectionately praises both his own birthplace and the great city itself. Sophocles won his first victory at the Dionysian dramatic festival in 468, however, defeating the great Aeschylus in the process. This began a career of unparalleled success and longevity. In total, Sophocles wrote 123 dramas for the festivals. Since each author who was chosen to enter the competition usually presented four plays, this means he must have competed about 30 times. Sophocles won perhaps as many as 24 victories, compared to 13 for Aeschylus and four for Euripides, and indeed he may have never received lower than second place in the competitions he entered. “Sophocles.” Encyclopedia Britannica, 2013. Web. 22 September 2013. <http://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/554733/Sophocles>. Greek Theaters Greek tragedies and comedies were always performed in outdoor theaters. Early Greek theaters were probably little more than open areas in city centers or next to hillsides where the audience, standing or sitting, could watch and listen to the chorus singing about the exploits of a god or hero. From the late 6th century BC to the 4th and 3rd centuries BC there was a gradual evolution towards more elaborate theater structures, but the basic layout of the Greek theater remained the same. The major components of Greek theater are labeled on the diagram above. Orchestra: The orchestra (literally, "dancing space") was normally circular. It was a level space where the chorus would dance, sing, and interact with the actors who were on the stage near the skene. The earliest orchestras were simply made of hard earth, but in the Classical period some orchestras began to be paved with marble and other materials. In the center of the orchestra there was often a thymele, or altar. The orchestra of the theater of Dionysus in Athens was about 60 feet in diameter. Theatron: The theatron (literally, "viewing-place") is where the spectators sat. The theatron was usually part of hillside overlooking the orchestra, and often wrapped around a large portion of the orchestra (see the diagram above). Spectators in the fifth century BC probably sat on cushions or boards, but by the fourth century the theatron of many Greek theaters had marble seats. Skene: The skene (literally, "tent") was the building directly behind the stage. During the 5th century, the stage of the theater of Dionysus in Athens was probably raised only two or three steps above the level of the orchestra, and was perhaps 25 feet wide and 10 feet deep. The skene was directly in back of the stage, and was usually decorated as a palace, temple, or other building, depending on the needs of the play. It had at least one set of doors, and actors could make entrances and exits through them. There was also access to the roof of the skene from behind, so that actors playing gods and other characters (such as the Watchman at the beginning of Aeschylus' Agamemnon) could appear on the roof, if needed. Parodos: The parodoi (literally, "passageways") are the paths by which the chorus and some actors (such as those representing messengers or people returning from abroad) made their entrances and exits. The audience also used them to enter and exit the theater before and after the performance. Englert, Walter. Ancient Greek Theater. Reed Library. Web. 22 September 2013. <http://academic.reed.edu/humanities/110tech/theater.html#staging>. Mystery of Greek Amphitheater's Amazing Sound Finally Solved The ancient mystery surrounding the great acoustics of the theater at Epidaurus in Greece has been solved. The theater, dating to the 4th century B.C. and arranged in 55 semi-circular rows, remains the great masterwork of Polykleitos the Younger. Audiences of up to an estimated 14,000 have long been able to hear actors and musicians--unamplified--from even the back row of the architectural masterpiece. How this sonic quality was achieved has been the source of academic and amateur speculation, with some theories suggesting that prevailing winds carried sounds or masks amplified voices. It's in the seats Now, researchers at the Georgia Institute of Technology have discovered that the limestone material of the seats provide a filtering effect, suppressing low frequencies of voices, thus minimizing background crowd noise. Further, the rows of limestone seats reflect high-frequencies back towards the audience, enhancing the effect. Researcher Nico Declercq, a mechanical engineer, initially suspected that the slope of the theater had something to do with the effect. "When I first tackled this problem, I thought that the effect of the splendid acoustics was due to surface waves climbing the theater with almost no damping," Declercq said. "While the voices of the performers were being carried, I didn't anticipate that the low frequencies of speech were also filtered out to some extent." However, experiments with ultrasonic waves and numerical models indicated that frequencies up to 500 hertz (cycles per second) were lowered, and frequencies higher than 500 hertz went undiminished, he said. Acoustic traps The corrugations on the surface of the seats act as natural acoustic traps. Though this effect would seem to also remove the low frequencies from the actors' voices, listeners actually fill in the missing portion of the audio spectrum through a phenomenon known as virtual pitch. The human brain reconstructs the missing frequencies, producing the virtual pitch phenomenon, as in listening to someone speaking on a telephone with no low end. The findings are detailed in the April issue of the Journal of the Acoustics Society of America. Amazingly, the Greek builders of the theater did not themselves understand the principles that led to the exceptional audibility of sound from the stage. Attempts to recreate the Epidaurus design never quite matched the original. Later seating arrangements featured other materials, such as wood for the benches, an approach which may have ultimately derailed the design duplication effort. Chao, Tom. “Mystery of Greek Amphitheater’s Amazing Sound Finally Solved.” Live Science, 5 April 2007. Web. 22 September 2013. <http://www.livescience.com/7269-mystery-greek-amphitheateramazing-sound-finally-solved.html>. The Myth of Dionysus Dionysus is commonly thought to have been the son of Zeus, the most powerful of all Greek gods and goddesses, and Semele, a mortal woman. Zeus' wife, Hera, was extremely jealous and planned the death of Dionysus. Zeus was able to save the child; he sent Dionysus away with Hermes, who took him to Mt. Nysa to be raised by the half-human, half-goat creatures known as satyrs. When he was older, Dionysus is said to have discovered the grapevine. He taught mankind how to cultivate the vine and make wine from the grapes. Dionysus became the god of wine. He was also associated with the madness and revelry that goes with it. The Festival Four times a year, the Athenians and citizens from all over Greece would gather together to worship Dionysus. The largest and most prolific of these festivals was the Great Dionysia, which was held in late March through early April. Here, the Greeks would sing and dance and revel in a state of madness in worship of the god. Goats were sacrificed in his honor. Men would dress up as satyrs. Large amounts of wine would be consumed. Tragedy began here, at the City Dionysia, in the sixth century B.C.E. Few records are left that date prior to 534 B.C.E., but we do know that at some point a contest was formed to honor the best tragedy. In 534, Athens made the contests official and offered financial support for their production. Once made official, the contests and their winners were recorded by the state, giving us much more detail about the tragic contests. On the first day of festivities, a large statue of Dionysus was carried from the temple to the Theater of Dionysus at the foot of the Acropolis. This procession was of much importance to the Athenians and Greeks and large numbers of people attended the parade. The procession itself was a spectacle, and intended as a reenactment of Dionysus' journey to Athens. Once at the theater and prior to the performance of the plays, the theater was sprinkled with the blood of sacrificial pigs for purification. The festival allowed three playwrights to have their plays performed in the tragic contests. Each contestant was required to submit three tragedies and one satyr play (a form of comedy that required the chorus to dress as the satyr companions of Dionysus). It is assumed that the tragedies were required to be in the form of a trilogy. While only one complete Greek trilogy remains, many of the surviving tragedies seem to have once been a part of a trilogy. The contest lasted for three days, one for each playwright. Each playwright presented all three tragedies and the satyr play in one day. The audiences would spend much of the day in the theater, though Greek plays were shorter than modern plays. After the three days of performances, the winner would be put to a vote. Taylor, Bryan D. “Theater in Ancient Greece: The Festival of Dionysus.” Bright Hub Education, 6 January 2012. Web. 22 September 2013. <http://www.brighthubeducation.com/homework-helpliterature/64195-festival-of-dionysus/>. Origins of "Theater" As We Know It The whole idea of performing songs and dances for an audience originated as a way to worship the god Dionysus, who first appeared in Greece in the area north of Attica known as Boeotia. The people honored this son of Zeus by accepting his gift of knowledge (how to cultivate grapes for wine) and establishing a cult (a whole system of worship) in his name . When Dionysus came to Attica, a local king also accepted this new knowledge, but his people - who had never tasted the effects of wine before feared they had been poisoned and killed the king. They suffered a terrible punishment and thereafter knew the divinity of Dionysus - then they too established a cult and a festival in his honor every winter. Women ran wild in orgiastic ecstasy, all in hope that the dead world would once again come back to life after the winter was over. Another big festival was held in the spring to celebrate the renewal of life, even more elaborate and ecstatic: men dressed in goat-skins, or tragados (imitating satyrs, mythical half goat/half man creatures -- they represented nature and fertility) and sang songs of praise to the god (odi tragon, "goat-song" is the etymology of our word "tragedy.") Festival of Dionysus Introduced to Athens This crude celebration of bountiful grape harvests gradually grew into a more formalized production, and by the time of the fifth century, drama became the number one public opinion-setting institution of the new democratic polis. This is one of the reasons that "Greek" drama as we know it through the grand masters of Euripides, Aristophanes... is almost exclusively "Athenian" drama. The tyrant Pesistratus introduced the cult of Dionysus to Athens in the 6th century and "theater" as we know it was born. There were four separate festivals of Dionysus, but it was at the Greater (or City) Dionysia, celebrated by all of Attica in the spring, where poet-playwrights competed for top prizes. This is not unlike the Olympics, which also sprang from religious ritual but appealed to the Greek competitive spirit at the same time. Thespis (where we get our word "thespian" from) is known to have won the first competition (534 BC). In Thespis' time, the dramatist not only wrote the play, but he also composed the music, choreographed the dance, designed the costumes, and played the major role; citizens paid for all the expenses (including the actors' pay, their masks and costumes, the sets...). In the early days, a panel of judges determined the winner of the competition. Siegel, Janice. Dr. J’s Illustrated Greek Drama. 26 November 2005. Web. 22 September 2013. <http://people.hsc.edu/drjclassics/lectures/theater/ancient_Greek_drama.shtm>. All the actors were men or boys. Dancers and singers, called the chorus, performed on a flat area called the orchestra. Over time, solo actors also took part, and a raised stage became part of the theatre. The actors changed costumes in a hut called the "skene". Painting the walls of the hut made the first scenery. “Ancient Greeks: Arts and Theater.” BBC Primary History, 2013. Web. 22 September 2013. <http://www.bbc.co.uk/schools/primaryhistory/ancient_greeks/arts_and_theatre/>. At the early Greek festivals, the actors, directors, and dramatists were all the same person. Later, only three actors could be used in each play. After some time, non-speaking roles were allowed to perform on-stage. Because of the limited number of actors allowed onstage, the chorus evolved into a very active part of Greek theatre. Though the number of people in the chorus is not clear, the chorus was given as many as one-half the total lines of the play. Music was often played during the chorus' delivery of its lines. “Theatre.” Ancient Greece. University Press, Inc. 2003-2012. Web. 22 September 2013. < http://www.ancientgreece.com/s/Theatre/>. In tragic plays of Ancient Greece, the chorus (choros) was originally made up of 12 singing and dancing members (choreutai). The whole chorus tried to stay in rhythm with each other so they could be viewed as one entity rather than separate entities. After a while, the members of the Chorus increased up to 15, divided into two sub-choruses of 6 (hemichoria) and a leader (koryphaios); the number of actors increased from two to three. The leader of the chorus interacted with the characters in the play, and spoke for the general population (the play's public opinion). This change, attributed to Sophocles, favored the interaction between actors and thus brought ancient Greek tragedy closer to the modern notion of dramatic plot. The chorus usually communicated in song form, but sometimes the message was spoken. It was the author's job to choreograph the chorus. The chorus offered background and summary information to help the audience follow the performance, commented on main themes, and showed how an ideal audience might react to the drama as it was presented. They also represent the general populace of any particular story. In the second generation of Athenian tragedy the chorus often had a more substantial role in the narrative; in Euripedes' Bacchae, for example, the chorus, representing the frenzied female worshippers of Dionysus becomes a central character in itself. “Ancient Greek Theater.” Web. 22 September 2013. <http://www.crystalinks.com/greektheater.html>. Actors and Acting in Ancient Greece Besides the chorus, only three actors performed all the speaking roles in tragedies produced at the Dionysia, although the authorities who oversaw these celebrations of Dionysus allowed on stage any number of mute actors. These non-speaking parts were probably played by young actors-in-training whose voices were not as yet fully matured and could not project well enough to be heard throughout the enormous arenas encompassed by classical theatres. But all known tragedies include more than three speaking characters, which means actors must have taken more than one role in a play. Role-changing was perfectly practical on the Athenian stage, not only because the majority of the viewers sat some distance from the stage but, more important, because the actors wore masks and costumes facilitating their ability to play different parts. That is to say, within the scope of a single tragedy, an actor might portray as many as five different characters, sometimes very different ones, with relative ease since altering his façade through a change of mask and costume was a traditional element in Greek theatre. Indeed, the ancient Greek actor was expected to be able to impersonate the full range of humanity, from young girls to old men, by adapting his voice and mannerisms. And, as in some performance genres found there, men played all parts, male and female. Furthermore, it is clear that three actors portrayed all the roles in any classical drama, a tendency today called the "three-actor rule." The surviving dramas of this period show this rule in action, for the simple reason that all such drama—even the surviving fragments!—require no more than three speaking characters on stage at once. Less clear is why there were only three actors. Presumably, having performers play more than one role was a traditional component of the Greek theatre, perhaps from the very inception of Greek drama when there was but one actor and a chorus. Equally compelling is surely the jealousy of premier performers in competition with one another for a prestigious honor at the Dionysia in the later Classical Age, which must also have encouraged holding the numbers of speaking performers down. By the middle of the century, actors were installed as a fixture in the Athenian theatre. At some point in the 440's BCE they started receiving their own awards at the Dionysia, a clear recognition of their growing role in theatre. That this began shortly after Sophocles separated playwriting and acting should come as no surprise. No longer the subordinates of a playwright who hired them so he could have a dialogue partner, actors were becoming their own independent artists, much as they are today, and without the playwright to outshine them on stage their prestige ballooned. Indeed, by the fourth century the best-known names in theatre, stars like Polos and Neoptolemos, belonged not to playwrights but actors. Around that time, the theatre which has never been without its caste systems evolved a hierarchy of performers. Later—perhaps much later since we do not know the date—separate words evolved referring to the three different actors: protagonist, deuteragonist and tritagonist, meaning respectively "first competitor," "second competitor" and "third competitor." In post-classical Greece, these terms came to carry connotations of quality, too. So, for instance, tritagonist could imply "third-rate." “Classical Greek Tragedy and Theater.” Classical Drama and Society, 2012. Web. 22 September 2013. <http://www.usu.edu/markdamen/ClasDram/chapters/061gkthea.htm>. Masks Masks served several important purposes in Ancient Greek theater: their exaggerated expressions helped define the characters the actors were playing; they allowed actors to play more than one role (or gender); they helped audience members in the distant seats see and, by projecting sound somewhat like a small megaphone, even hear the characters better. In a tragedy, masks were more life-like; in a comedy or satyr play, masks were ugly and grotesque. Masks were constructed out of lightweight materials such as wood, linen, cork, and sometimes real hair. Unfortunately, they lacked durability, and none has survived. Costumes Costumes, along with masks and props, helped indicate the social status, gender, and age of a character. Athenian characters wore more elaborate, decorated versions of everyday clothing, such as a tunic or undergarment (chitôn or peplos), a cloak or over-garment (himation). Costumes for characters that were non-Athenians were more outlandish. Tragic actors wore buskins (raised platform shoes) to symbolize superior status, while comic actors wore plain socks. When depicting women, actors wore body stockings to make their bodies appear feminine. Some plays even called for actors to wear animal costumes. Props In addition to masks, actors also used props to create a character. These could be a crown to represent a king; a lyre for a musician; a walking stick to suggest age; spears and helmets to suggest military men. A "props-maker" (skeuopoios) would create and provide these to the actors. Props can also be used for symbolism, as in the red carpet Agamemnon walks on when he returns home from war, signifying the blood he spilled at Troy. Special Props Ekkyklêma—Literally, "wheel out," a large wheeled platform that could be rolled out to display scenes that had taken place beyond the view of the spectators (usually the results of violent acts since those never took place on stage). Mêchanê/Krane—Literally, "machine," a crane-like device used to lift actors, allowing performers to appear in the air or to enter dramatically from behind the skene (which was a common method of portraying the gods). “City Dionysia: The Ancient Roots of Modern Theater.” Arts Edge: The Kennedy Center. Web. 22 September 2013. <http://artsedge.kennedy-center.org/interactives/greece/theater/players Props.html>. Costumes and masks The actors were so far away from the audience that without the aid of exaggerated costumes and masks, they would be difficult to see. Actors wore thick boots to add to their height and gloves to exaggerate their hands so that their movements would be discernible to the audience. The mask is the best-known symbol of Greek theatre. A distinctive mask was made for each character in a play. The masks were made of linen or cork, so none have survived. We know what they looked like from statues and paintings of ancient Greek actors. Tragic masks carried mournful or pained expressions, while comic masks were smiling or leering. An actor's entire head was covered by his mask, which included hair. It has been theorized that the shape of the mask amplified the actor's voice, making his words easier for the audience to hear. “Greek Theater.” Web. 22 September 2013. <http://www.mlahanas.de/Greeks/LX/GreekTheater.html>. Skene The back of the orchestra, the one side that did not face the theatron, housed the skene, or "hut." The skene was an enclosure about 100 feet long that was probably originally used as a dressing-room for the performers. As the art of theatre developed, it came to be used more and more as scenery. The skene had three doors to the orchestra; its edges bent forward into the orchestra like wings. Between these wings was a raised step that was used as a second level of the stage. Sets The Theater of Dionysus was too large for realistic sets or for many props: they would not have been visible to the audience. The earliest Greek plays were closer to religious rituals than to theatre and probably did not have any sets at all. When painted sets did come into use, they were stylised representations of familiar locations that audiences expected to see in plays, like palaces, forests and temples. These were erected between the doors on the skene. Effects Ancient Greek plays required a few special effects, like characters flying and gods descending. For this the ancient Greeks used a crane, housed on top of the skene, to lift the actors when necessary. Horses and chariots would also come on stage with the protagonist the first time he entered, as a signal to the audience that this was the hero. For actions that could not be realistically performed live, such as Oedipus gouging out his own eyes, the actors would exit into the skene and leave the door open behind them. This allowed their voices to travel to the audience while keeping the action itself out of sight. Mitchell, Stephanie. “What Type of Scenery Was Used in Ancient Greek Theater?” EHow UK Lifestyle. Web. 22 September 2013. <http://www.ehow.co.uk/info_8237112_typeused-ancient-greek-theater.html>.