* Your assessment is very important for improving the work of artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download Relation between QT duration and maximal wall thickness in familial

Management of acute coronary syndrome wikipedia , lookup

Cardiac contractility modulation wikipedia , lookup

Myocardial infarction wikipedia , lookup

Electrocardiography wikipedia , lookup

Quantium Medical Cardiac Output wikipedia , lookup

Heart arrhythmia wikipedia , lookup

Ventricular fibrillation wikipedia , lookup

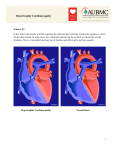

Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy wikipedia , lookup

Arrhythmogenic right ventricular dysplasia wikipedia , lookup

Downloaded from http://heart.bmj.com/ on May 11, 2017 - Published by group.bmj.com 153 CARDIOVASCULAR MEDICINE Relation between QT duration and maximal wall thickness in familial hypertrophic cardiomyopathy X Jouven, A Hagege, P Charron, L Carrier, O Dubourg, J M Langlard, S Aliaga, J B Bouhour, K Schwartz, M Desnos, M Komajda ............................................................................................................................. Heart 2002;88:153–157 See end of article for authors’ affiliations ....................... Correspondence to: Dr Xavier Jouven, Service de Cardiologie, Hôpital Européen Georges Pompidou, 20 rue Leblanc, 75015 Paris, France; xavier.jouven@ hop.egp.ap-hop-paris.fr Accepted 17 April 2002 ....................... Background: QT abnormalities have been reported in left ventricular hypertrophy and hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Objective: To determine the relation between left ventricular hypertrophy and increased QT interval in familial hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Methods: The QT interval was measured in 206 genotyped adult subjects with familial hypertrophic cardiomyopathy from 15 unrelated families carrying mutations in the β myosin heavy chain (β-MHC) gene (five families, n = 68) or the cardiac myosin binding protein C (MyBPC) gene (10 families, n = 138). Subjects were classified as genetically unaffected (controls, n = 112), affected with left ventricular hypertrophy (penetrants, n = 58), or affected without left ventricular hypertrophy (non-penetrants, n = 36). Results: There was a significant increase in QTmax and QTmin from controls to non-penetrants and penetrants for both the MyBPC group (p < 0.001 and p < 0.001, respectively) and the β-MHC group (p < 0.001 and p < 0.001, respectively). In the MyBPC group, the increase in the QT interval could be explained by increased left ventricular hypertrophy. In the β-MHC group, non-penetrants had a significantly longer QTmax than controls despite the absence of left ventricular hypertrophy, and a similar QT interval to penetrants despite a lesser degree of left ventricular hypertrophy. Conclusions: In familial hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, genetically affected subjects without left ventricular hypertrophy may have a prolonged QT duration, which depends not only on the degree of left ventricular hypertrophy, when present, but also on the causative mutation. H ypertrophic cardiomyopathy is associated with an increased risk of ventricular tachyarrhythmias and sudden death.1–6 A prolonged QT interval and increased QT dispersion (QTd) have been observed in affected individuals7–13 and may contribute to the occurrence of ventricular arrhythmias. However, the relations between left ventricular hypertrophy, increased QT interval, and QTd are unclear.8 11 13 In hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, it is not known whether these abnormalities only reflect the increased myocardial thickness, or whether they are a result of the genetic mutation. If the latter were true, it might explain the occurrence of sudden death among genetically affected subjects without left ventricular hypertrophy.14 15 Molecular genetic studies in individuals with familial hypertrophic cardiomyopathy16 17 can discriminate between those not genetically affected, those who are affected and have ECG or echocardiographic abnormalities (penetrants), and those who are affected but do not have ECG or echocardiographic abnormalities (non-penetrants). The QT interval and QT dispersion have not been characterised in genotyped cases of familial hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Furthermore, we know nothing about the behaviour of QT in non-penetrants. Our aim in this study was therefore to assess the QT interval and QT dispersion in a large genotyped cohort of adult cases of familial hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. METHODS Population Persons with known causative mutations from among genotyped families with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy16 17 were included in the study. Informed consent was obtained in accordance with a study protocol approved by the ethics committee of the Centre Hospitalier Universitaire de la PitiéSalpetrière. The subjects had an ECG and a physical and Doppler echocardiographic examination, and provided blood samples for laboratory tests. Those with a clinical cause for left ventricular hypertrophy, such as valvar heart disease or high blood pressure, and anyone being treated with amiodarone or sotalol were excluded from the analyses. Because of age related changes in myocardial thickness in children, subjects under the age of 18 were excluded. QT measurements A standard 12 lead ECG was recorded in all subject at 25 mm/s paper speed with a 10 mm/mV gain. Measurements of ECG intervals were performed manually, using a standardised approach. The QT interval was measured from the onset of the QRS complex to the end of the T wave at the level of the isoelectric baseline. In the presence of a U wave, the end of the T wave was assessed using the most similar pattern of the 16 possible combinations of T and U waves schematised by Lepeschkin and Surawicz.18 When the end of the T wave could not be determined reliably or when the T wave was of very low amplitude (< 1 mm), the lead was excluded from the analysis. An average of three consecutive cycles for each lead was obtained. The QT interval was corrected for heart rate using Hodges’s linear correction19: QTc = QT + 1.75(heart rate − 60) QTd was defined as the difference between maximum (QTcmax) and minimum (QTcmin) values of the QT intervals ............................................................. Abbreviations: β-MHC, β-myosin heavy chain; MyBPC, cardiac myosin binding protein C; QTc, corrected QT; QTd, QT dispersion www.heartjnl.com Downloaded from http://heart.bmj.com/ on May 11, 2017 - Published by group.bmj.com 154 in any of the 12 leads in which it was measured. Because of the linearity, rate correction is unnecessary (that is, with Hodge’s formula, QTd calculated from corrected QT intervals is identical to QTd calculated from uncorrected intervals). All measurements were performed by the same investigator using this standardised approach, blinded to the clinical, genetic, and echocardiographic diagnosis. Subjects with atrial fibrillation or complete bundle branch block, or in whom QT interval measurement was only possible in fewer than eight leads, were excluded from analysis. Reproducibility assessment Thirty ECGs were randomly reanalysed to assess the intraobserver reproducibility of QT interval measurements. The largest mean intraobserver QT error was noticed in lead III (2.2%) and the lowest in lead V3 (1%). The ranges and means (SD) of the intraobserver error, with paired t tests, were respectively: for Qtmax: 0–30 ms; 2 (8) ms (NS) for Qtmin: 0–30 ms; −4 (14) ms (NS) for QTd: 0–50 ms, 10 (18) ms (p = 0.01) Genetic analysis Genotypic assessments were obtained from family members using amplification, polymerase chain reaction, microsatellite typing, and sequencing techniques as previously described.20 21 Fifteen families with 12 different mutations were studied: five families were associated with four mutations in the β-myosin heavy chain (β-MHC) gene (Arg403Leu, Arg719Trp, Arg723Cys, Glu483Lys), and 10 families were associated with eight mutations in the cardiac myosin binding protein C gene (DelExon25, SASint7, SASint20, Glu542Gln, SASint23, SASint11, BPint23, DelExon33). Echocardiographic analysis Cross sectional echocardiographic examinations were performed in three separate institutions with standard echocardiographic systems. Ultrasonic images were obtained in cross sectional planes using standard transducer positions, and stored on VHS videotape for subsequent analysis. All echocardiographic measurements were performed in a core laboratory by three senior echocardiographists who read the recording blindly and without knowledge of the genetic diagnosis. M mode measurements of end diastolic left ventricular wall thickness were made at the onset of the QRS complex, according to the recommendations of the American Society of Echocardiography. In cases of disagreement, analyses were reviewed by the three readers and definitive agreement achieved. Penetrance of the disease The penetrance of the disease was determined as previously described.17 In brief, the criteria used (in the absence of any cause of left ventricular hypertrophy) were as follows: (1) a maximum left ventricular end diastolic wall thickness > 13 mm (2) the presence of major abnormalities on the ECG—that is, left ventricular hypertrophy assessed by a Romhilt–Estes score of > 4,22 Q waves of > 0.04 s or more than one third of the width of the R wave, or significant ST–T segment changes (3) a combination of (1) and (2). Statistical analysis Values are expressed as mean (SD). As individuals within a family were not independent, conventional statistical procedures could not be used. Statistical analyses were carried out using the estimating equations technique proposed by Liang and Zeger.23 SAS procedures (Statistical Analysis System, Cary, North Carolina, USA) were used for analysis. Within both the www.heartjnl.com Jouven, Hagege, Charron, et al β-MHC group and the MyBPC group, characteristics of controls, non-penetrants, and penetrants were compared using variance analysis and global tests for linear trend when indicated (GENMOD procedures, with a probability value of p < 0.01 considered as significant). Correlations were assessed using Spearman’s comparison of ranks. RESULTS Study group Among the 273 genotyped subjects, 67 were excluded from the analysis. Causes of exclusion were the following: age < 18 years (n = 40); another cause of left ventricular hypertrophy (n = 3); atrial fibrillation (n = 3); complete bundle branch block (n = 10); amiodarone or sotalol treatment (n = 5); and QT intervals measurements in fewer than eight of the 12 leads (n = 6). The remaining 206 adults, coming from 15 unrelated families, completed clinical, ECG, biological, genetic, and echocardiographic examinations. There were 112 men and 94 women, with a mean (SD) age of 39.4 (15.8) years (range 18–91 years). Ninety four subjects were genetically affected, including 58 penetrants and 36 non-penetrants. Overall, 138 subjects came from 10 families carrying mutations in the MyBPC gene encoding for the sarcomeric protein C (79 controls, 24 non-penetrants, and 35 penetrants), and 68 subjects came from five families carrying mutations in the β-MHC gene encoding for the β-myosin heavy chain (33 controls, 12 non-penetrants, and 23 penetrants). No significant difference was observed between the 10 families with mutations in the MyBPC gene, or between the five families with mutations in the β-MHC gene. The families were therefore pooled into two groups (MyBPC group and β-MHC group). The characteristics of controls, nonpenetrants, and penetrants are compared in table 1. In neither group were the sex ratio, body mass index, heart rate, or systolic and diastolic blood pressure significantly different between controls, non-penetrants, or penetrants. In the MyBPC group only, penetrant subjects were significantly older than non-penetrant subjects and controls. In the MyBPC and β-MHC groups, there was a significant trend towards a linear increase in maximum wall thickness (p < 0.001 and p < 0.001, respectively), left atrial diameter (p < 0.001 and p < 0.01), and myocardial mass index (p < 0.001 and p < 0.001) from controls, through nonpenetrant subjects, to penetrant subjects. The maximum wall thickness was greater in penetrants with a mutation in the β-MHC gene than in those with a mutation in the MyBPC gene (20.9 (4.8) mm v 17.6 (4.6) mm, p < 0.001), while it was comparable in the non-penetrants (9.8 (1.8) mm v 10.4 (1.7) mm, NS) and the controls (10.2 (2.2) mm v 9.2 (1.6) mm, NS). Among penetrant subjects, the following variables were not statistically different between the MyBPC and the β-MHC groups: left ventricular outflow tract gradient > 30 mm Hg (11.6% v 4.3%, NS); mitral valve systolic anterior motion (25.7% v 39.1%, NS); and abnormal T waves (57.1% v 43.5%, NS). QT analysis There was a linear trend in all 12 leads towards an increase in QTc interval (p < 0.01), QTcmax (p < 0.0001), and QTcmin (p < 0.0001), but only a non-significant trend in QTd (p < 0.02) from controls, through non-penetrant subjects, to penetrant subjects in the MyBPC group. In this group, QTcmax and QTcmin values in the penetrants remained significantly different from the values in the non-penetrants (p < 0.0003 and p < 0.01, respectively), while there was no difference between non-penetrants and controls (p < 0.03 and NS, respectively) (fig 1). Downloaded from http://heart.bmj.com/ on May 11, 2017 - Published by group.bmj.com QT duration and wall thickness in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy 155 Table 1 Clinical and echocardiographic data on controls, non-penetrants, and penetrants from families carrying mutations in the cardiac myosin binding protein C or β myosin heavy chain genes β-MHC MyBPC Male/female Age (years) Heart rate (beats/min) BMI (kg/m2) Systolic BP (mm Hg) MWT (mm) LA diameter (mm) LVMI (g/m2) Controls (n=79) Non-penetrants (n=24) Penetrants (n=35) p Value* Controls (n=33) Non-penetrants (n=12) Penetrants (n=23) p Value* 37/42 37 (14) 68 (10) 23.5 (3.6) 124 (11) 9.2 (1.6) 33 (6) 37.8 (7.0) 10/14 38 (19) 65 (12) 23.8 (3.1) 126 (12) 10.4 (1.7) 35 (4) 40.6 (8.0) 23/12 45 (15) 66 (17) 24.7 (2.8) 124 (11) 17.6 (4.6) 41 (9) 57.9 (12.4) NS 0.02 NS NS NS 0.0001 0.0001 0.0001 19/14 39 (14) 73 (17) 22.8 (3.1) 128 (9) 10.2 (2.2) 34 (5) 36.6 (8.5) 6/6 34 (12) 69 (17) 21.6 (2.8) 119 (8) 9.8 (1.8) 35 (4) 37.4 (10.0) 14/9 42 (15) 65 (12) 23.7 (3.4) 132 (21) 20.9 (4.8) 40 (9) 63.7 (12.5) NS NS NS NS NS 0.0001 0.03 0.0001 Values are n or mean (SD). *p Values for global variance analysis. β-MHC, β-myosin heavy chain gene; BMI, body mass index; BP, blood pressure; LA, left atrial; LVMI, left ventricular mass index; MyBPC, cardiac myosin binding protein C gene; non-penetrant, genetically affected but no left ventricular hypertrophy; penetrant, genetically affected with left ventricular hypertrophy. Similarly in the β-MHC group, there was a trend for a linear increase in QTc interval in all leads (p < 0.01) excepted L1 (p < 0.03) and L2 (p < 0.02), in QTcmax (p < 0.0001), and in QTcmin (p < 0.0001), but not QTd, from controls, through non-penetrant subjects, to penetrant subjects. In all leads, the QTc intervals of non-penetrants were similar to the values in penetrants. Finally, the differences in QTcmax and QTcmin between penetrant and non-penetrant subjects were not significant, while the difference between non-penetrants and controls remained significant (p < 0.01 and p < 0.01, respectively). In penetrant subjects, Qtcmax was longer in patients with a mutation on the MyBPC gene than in those with a mutation on the β-MHC gene (450 (32) ms v 435 (22) ms, p < 0.01), but there was no significant difference in the prevalence of complete bundle branch block and electrical left ventricular Figure 1 QTcmax, QTcmin, QTd, and maximum wall thickness in controls, non-penetrant subjects, and penetrant subjects in subjects originating from families with mutations in the MyBPC or β-MHC genes; p value for 2×2 tests. β-MHC, β-myosin heavy chain; C, control; MWT, maximum wall thickness; MyBPC, cardiac myosin binding protein C; NP, non-penetrant: genetically affected but no left ventricular hypertrophy; P, penetrant: genetically affected with left ventricular hypertrophy; QTc, corrected QT interval; QTd, QT dispersion. www.heartjnl.com Downloaded from http://heart.bmj.com/ on May 11, 2017 - Published by group.bmj.com 156 Jouven, Hagege, Charron, et al Figure 2 Correlations between QTcmax and maximum wall thickness in subjects with mutations in the MyBPC or β-MHC genes; p value for Spearman rank correlations. β-MHC, β-myosin heavy chain; MWT, maximum wall thickness; MyBPC, cardiac myosin binding protein C; QTc, corrected QT interval. hypertrophy between the two groups. In non-penetrants and controls, Qtcmax was not significantly different between the two groups. The positive correlation (fig 2) of maximum wall thickness with QTcmax and QTcmin in genetically affected subjects (non-penetrants and penetrants) was significant in the MyBPC group (r = 0.41, p = 0.002; and r = 0.29, p = 0.01, respectively) but not in the β-MHC group (r = 0.22, NS; and r = 0.08, NS). DISCUSSION end diastolic wall thickness of more than 13 mm and/or the presence of major abnormalities on the ECG (left ventricular hypertrophy, Q waves, and significant ST–T segment changes). On the other hand, in view of the prolonged QT interval, it is questionable whether such individuals should be classed as truly non-penetrant. The prolonged QT interval may increase the risk of ventricular arrhythmias and could explain the occurrence of sudden death in patients with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy in the absence of left ventricular hypertrophy, as reported previously.14 15 QT duration and myocardial hypertrophy In penetrant subjects, and despite a smaller maximum wall thickness, patients with a mutation on the MyBPC gene had a longer Qtcmax than those with a mutation on the β-MHC gene. Mutations in the MyBPC or β-MHC genes showed different patterns with respect to the QT interval. In the MyBPC group there was a similar pattern of increase in maximum wall thickness, QTcmax, and QTcmin between controls, non-penetrants, and penetrants, and the correlation between QTcmax (or QTcmin) and maximum wall thickness was significant. These findings suggest that the increased QT interval observed in individuals with mutations in the MyBPC gene is related to myocardial hypertrophy. On the other hand, in subjects with a mutation in the β-MHC gene, nonpenetrants had significant prolongation of QTcmax and Qtcmin, despite the absence of left ventricular hypertrophy in this group. The non-penetrants had similar QTcmax and QTcmin values to the penetrants, despite pronounced differences in maximum wall thickness. Thus in mutations of the β-MHC gene, a prolonged QT interval does not appear to be related solely to myocardial hypertrophy. Possible mechanisms Mechanisms other than myocardial hypertrophy could be involved in QT prolongation. Hyperreactivity of the adrenergic system and an imbalance in sympathetic/parasympathetic tone have been described in patients with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy.24 25 Slight differences in sympathetic tone, which affect the RR interval to a minor degree, have been shown to cause much greater differences in QT intervals in patients with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy compared with controls.25 Thus the response of the ventricular myocardium to changes in sympathetic tone may be increased in patients with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Regional myocardial fibrosis, scarring, or ischaemia have also been described in patients with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. In a recent study, Yoshida found perfusion abnormalities in 69% of such patients.26 A direct or indirect effect of the gene mutation on QT abnormalities cannot be excluded.27 Familial long QT syndrome is a disorder characterised by abnormal ventricular repolarisation, ventricular arrhythmias triggered by sympathetic nervous activation, and sudden death.28 In long QT syndrome it has been possible to trace specific mutations on ion channel genes, and numerous novel mutations have been described.29 Thus in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, mutations in the genes encoding for sarcomere proteins may interfere with genes encoding for channel subunits, and this could increase the QT interval independently of any myocardial hypertrophy. This hypothesis would conveniently explain the behaviour of the QT interval in individuals with the β-MHC gene mutation. QT abnormalities in non-penetrant subjects QTcmax and QTcmin were significantly longer in nonpenetrants carrying a mutation in the β-MHC gene than in controls. These subjects did not have the usual criteria of penetrance of the disease—that is, a maximum left ventricular Limitations Our findings were obtained in a selected population, and thus the conclusions are limited to families with mutations in the β-MHC and MyBPC genes. Moreover, because of the small differences between controls, non-penetrant subjects, and Up to now, QT abnormalities in patients with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy have only been described in non-genotyped populations. Published reports have concerned only case– control studies involving various different control populations (healthy volunteers or patients, stratified or not for age and sex), and various types of case (usually a combination of cases of sporadic and familial hypertrophic cardiomyopathy).7–13 www.heartjnl.com Downloaded from http://heart.bmj.com/ on May 11, 2017 - Published by group.bmj.com QT duration and wall thickness in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy penetrant subjects, the QT abnormalities cannot be used at the individual level for diagnosing hypertrophic cardiomyopathy within a family. No significant differences were observed between separate families with mutations within a given gene, but the power to detect such differences was low. Combining families into groups according to gene type (β-MHC or MyBPC) may have pooled individuals with very different forms of expression of the disease. However, in the absence of preliminary data, this approach appeared to be the most logical. When subjects treated with β blocking agents (n = 9) were excluded from the analysis, the results did not change significantly. Furthermore, as only penetrant subjects were treated with β blockers, this variable did not affect the differences in QT interval observed between the controls and the nonpenetrant subjects. Different methods have been described to measure the QT interval, and there is at present no gold standard. Manual measurements7–9 12 were used in the present study, with the usual limitations of that method—it is time consuming, there is high interobserver variability, and there is poor reproducibility.30 31 By using a single trained cardiologist with a standardised measurement, we eliminated interobserver variability and we increased the reproducibility, which was higher than previously reported.30 31 On the other hand, automatic measurements10 11 are faster and provide better reproducibility, though their reliability is still questioned, particularly in abnormal hearts.32 Finally, in a study to validate an automated method in patients with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, Savelieva and colleagues showed that both manual and automatic methods were suitable, but that they characterised different facets of the shape of the T wave.33 Manual measurements may reduce the differences in QT interval observed between controls, non-penetrants, and penetrants. The absence of significant differences in QTd between these three groups in our study could reflect both the unreliability of the measurements and a large overlap with the healthy population. Conclusions In familial hypertrophic cardiomyopathy associated with mutation of the β-MHC gene, the prolonged QT interval appears to be partially independent of myocardial hypertrophy. Further studies on other gene mutations will be useful in determining whether the QT abnormalities in this condition are related to prognosis. ..................... Authors’ affiliations X Jouven, A Hagege, S Aliaga, M Desnos, Service de Cardiologie, Hôpital Européen Georges Pompidou, Paris, France P Charron, M Komajda, Service de Cardiologie, Hôpital Pitié-Salpêtrière, Paris, France L Carrier, K Schwartz, INSERM Unit 153, Paris, France O Dubourg, Service de Cardiologie, Hôpital Ambroise Paré, Nantes, France J M Langlard, J B Bouhour, Service de Cardiologie, Hôpital Laennec, Nantes, France REFERENCES 1 Maron BJ, Roberts WC, Epstein SE. Sudden death in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: a profile of 78 patients. Circulation 1982;65:1388– 94. 2 McKenna WJ, Camm AJ. Sudden death in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: assessment of patients at high risk. Circulation 1989;80:1489–92. 3 Spirito P, Watson RM, Maron BJ. Relation between extent of left ventricular hypertrophy and occurrence of ventricular tachycardia in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Am J Cardiol 1987;60:1137–42. 157 4 Nicod P, Polikar R, Peterson KL. Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy and sudden death. N Engl J Med 1990;318:1255–7. 5 Fananapazir L, Tracy CM, Leon MB, et al. Electrophysiologic abnormalities in patients with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Circulation 1989;80:1259–68. 6 Miorelli M, Buja G, Melacini P, et al. QT-interval variability in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy patients with cardiac arrest. Int J Cardiol 1994;45:121–7. 7 Dritsas A, Sbarouni E, Gilligan D, et al. QT-interval abnormalities in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Clin Cardiol 1992;15:739–42. 8 Martin AB, Garson A, Perry JC. Prolonged QT interval in hypertrophic and dilated cardiomyopathy in children. Am Heart J 1994;127:64–70. 9 Buja G, Miorelli M, Turrini P, et al. Comparison of QT dispersion in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy between patients with and without ventricular arrhythmias and sudden death. Am J Cardiol 1993;72:973–6. 10 Zaidi M, Robert A, Fesler R, et al. Dispersion of ventricular repolarization in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. J Electrocardiol 1996;29:89–94. 11 Yi G, Elliott P, McKenna WJ, et al. QT dispersion and risk factors for sudden cardiac death in patients with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Am J Cardiol 1998;82:1514–19. 12 Kowey PR, Eisenberg R, Engel TR. Sustained arrhythmias in hypertrophic obstructive cardiomyopathy. N Engl J Med 1984;310:1566–9. 13 Engler RL, Smith P, Le Winter M, et al. The electrocardiogram in asymmetric septal hypertrophy. Chest 1979;75:167–73. 14 McKenna WJ, Stewart JT, Nihoyannopoulos P, et al. Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy without hypertrophy: two families with myocardial disarray in the absence of increased myocardial mass. Br Heart J 1990;63:287–90. 15 Maron BJ, Kragel AH, Roberts WC. Sudden death in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy with normal left ventricular mass. Br Heart J 1990;63:308–10. 16 Charron P, Dubourg O, Desnos M, et al. Clinical features and prognostic implications of familial hypertrophic cardiomyopathy related to the cardiac myosin-binding protein C gene. Circulation 1998;97:2230–6. 17 Charron P, Dubourg O, Desnos M, et al. Diagnostic value of electrocardiography and echocardiography for familial hypertrophic cardiomyopathy in a genotyped adult population. Circulation 1997;96:214–19. 18 Lepeschkin E, Surawicz B. The measurement of the QT interval of the electrocardiogram. Circulation 1952;5:378–87. 19 19 Macfarlane PW, McLaughlin SC, Rodger JC. Influence of lead selection and population on automated measurement of QT dispersion. Circulation 1998;98:2160–7. 20 Geisterfer-Lowrance AAT, Kass S, Tanigawa G, et al. A molecular basis for familial hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: a β-cardiac myosin heavy chain gene missense mutation. Cell 1990;62:999–1006. 21 Bonne G, Carrier L, Bercovici J, et al. Cardiac myosin binding protein C gene splice acceptor site mutation is associated with familial hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Nat Genet 1995;11:438–40. 22 Romhilt DW, Estes EH. Point score system for the ECG diagnosis of left ventricular hypertrophy. Am Heart J 1968;75:752–8. 23 Liang KY, Zeger SL. Longitudinal data analysis using generalized linear models. Biometrika 1986;73:13–22. 24 Maron BJ, Bonow RO, Cannon RO, et al. Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Interrelations of clinical manifestations, pathophysiology, and therapy. N Engl J Med 1987;316:780–9. 25 Yanagisawa-Miwa A, Inoue H, Sugimoto T. Diurnal change in QT intervals in dilated cardiomyopathy and hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Am J Cardiol 1991;67:1428–30. 26 Yoshida N, Ikeda H, Wada T, et al. Exercise-induced abnormal blood pressure responses are related to subendocardial ischemia in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. J Am Coll Cardiol 1998;32:1938–42. 27 Priori SG, Barhanin J, Hauer RNW, et al. Genetic and molecular basis of cardiac arrhythmias: impact on clinical management, part III. Circulation 1999;99:674–81. 28 Moss AJ, Schwartz PJ, Crampton RS, et al. The long QT syndrome: prospective longitudinal study on 382 families. Circulation 1991;84:1136–44. 29 Tanaka T, Nagai R, Tomoike H, et al. Four novel KVLQT1 and four novel HERG mutations in familial long QT syndrome. Circulation 1997;95:565–7. 30 Glancy JM, Weston PJ, Bhullar HK, et al. Reproducibility and automatic measurement of QT dispersion. Eur Heart J 1996;17:1035–9. 31 Murray A, McLaughlin NB, Bourke JP, et al. Errors in manual measurement of QT intervals. Br Heart J 1994;71:386–90. 32 McLaughlin NB, Campbell RWF, Murray A. Accuracy of four automatic QT measurement techniques in cardiac patients and healthy subjects. Heart 1996;76:422–6. 33 Savelieva I, Yi G, Guo XH, et al. Agreement and reproducibility of automatic versus manual measurement of QT interval and QT dispersion. Am J Cardiol 1998;81:471–7. www.heartjnl.com Downloaded from http://heart.bmj.com/ on May 11, 2017 - Published by group.bmj.com Relation between QT duration and maximal wall thickness in familial hypertrophic cardiomyopathy X Jouven, A Hagege, P Charron, L Carrier, O Dubourg, J M Langlard, S Aliaga, J B Bouhour, K Schwartz, M Desnos and M Komajda Heart 2002 88: 153-157 doi: 10.1136/heart.88.2.153 Updated information and services can be found at: http://heart.bmj.com/content/88/2/153 These include: References Email alerting service Topic Collections This article cites 32 articles, 15 of which you can access for free at: http://heart.bmj.com/content/88/2/153#BIBL Receive free email alerts when new articles cite this article. Sign up in the box at the top right corner of the online article. Articles on similar topics can be found in the following collections Drugs: cardiovascular system (8842) Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (314) Notes To request permissions go to: http://group.bmj.com/group/rights-licensing/permissions To order reprints go to: http://journals.bmj.com/cgi/reprintform To subscribe to BMJ go to: http://group.bmj.com/subscribe/