* Your assessment is very important for improving the workof artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download Bartonella henselae infection in a man with

Brucellosis wikipedia , lookup

Rocky Mountain spotted fever wikipedia , lookup

Dirofilaria immitis wikipedia , lookup

West Nile fever wikipedia , lookup

Carbapenem-resistant enterobacteriaceae wikipedia , lookup

Hepatitis C wikipedia , lookup

Middle East respiratory syndrome wikipedia , lookup

Trichinosis wikipedia , lookup

Leptospirosis wikipedia , lookup

Neisseria meningitidis wikipedia , lookup

Neonatal infection wikipedia , lookup

Marburg virus disease wikipedia , lookup

Schistosomiasis wikipedia , lookup

Coccidioidomycosis wikipedia , lookup

Hepatitis B wikipedia , lookup

Human cytomegalovirus wikipedia , lookup

Lymphocytic choriomeningitis wikipedia , lookup

Sarcocystis wikipedia , lookup

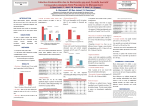

Journal of Medical Microbiology (2013), 62, 338–341 Case Report DOI 10.1099/jmm.0.052134-0 Bartonella henselae infection in a man with hypergammaglobulinaemia, splenomegaly and polyclonal plasmacytosis Nandhakumar Balakrishnan,1 Jaspaul S. Jawanda,2 Melissa B. Miller3 and Edward B. Breitschwerdt1 Correspondence Edward B. Breitschwerdt [email protected] 1 Intracellular Pathogens Research Laboratory, Center for Comparative Medicine and Translational Research, College of Veterinary Medicine, North Carolina State University, Raleigh, NC, USA 2 First Health Infectious Diseases, Moore Regional Hospital, 155 Memorial Drive, PO Box 3000, Pinehurst, NC, USA 3 Clinical Molecular Microbiology Laboratory, University of North Carolina School of Medicine, Chapel Hill, NC, USA Received 10 September 2012 Accepted 25 October 2012 Bartonella henselae is an infrequently reported cause of polyclonal plasmacytosis and hypergammaglobulinaemia. We herein document B. henselae infection in a 66-year-old patient who presented with hypergammaglobulinaemia, splenomegaly with polyclonal plasmacytosis, stroke, and suspected prosthetic aortic arch infection. Clinicians should remain cognizant of the heterogeneous clinical presentations associated with bartonellosis. Introduction Bartonella species are fastidious Gram-negative, arthropod-transmitted bacteria that are capable of causing long-lasting intraerythrocytic bacteraemia in mammals. Frequently reported disease manifestations include nonspecific malaise, adenitis, endocarditis and vasoproliferative lesions. As confirmation of Bartonella species infection by culture is the exception rather than the rule, serology, pathology and PCR amplification of organism-specific DNA sequences can facilitate diagnosis (Versalovic et al., 2011). The combination of hypergammaglobulinaemia, splenomegaly and polyclonal plasmacytosis is not known to have been reported in a human patient infected with a Bartonella species. Herein, we report a patient infected with Bartonella henselae that experienced hypergammaglobulinaemia, splenomegaly with polyclonal plasmacytosis, stroke and suspected infection of an aortic arch graft. Case report A retired 66-year-old male crop farmer had a history of atrial fibrillation, and placement of a coronary artery bypass graft, Dacron aortic arch graft and bioprosthetic aortic valve. He resided in a semi-rural area of North Carolina and had contact with outdoor cats. In July 2010, he reported persistent malaise, fatigue, low-grade fever and myalgia. Erythrocyte sedimentation rate was 84 mm h21; differential blood cell counts and a transthoracic echocardiogram were Abbreviations: anti-SSA, anti-Sjögren’s syndrome A; PET, positron emission tomography; POD, post operative day(s). 338 normal. A complete haemogram was unremarkable. Automated blood cultures (six sets obtained on three occasions) were negative. In September 2010, a temporal artery biopsy and rheumatologic evaluation were unrevealing, yielding a potential diagnosis of polymyalgia rheumatica. Antinuclear antibody by immunofluorescent antibody testing was negative, anti-Sjögren’s syndrome A (anti-SSA) antibodies were positive at a level of .8.0 antibody index units, with no clinical evidence of Sjogren’s syndrome. A magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scan defined only agerelated atrophy. Prednisone therapy was begun at 60 mg daily and then tapered to 10 mg daily after 2 months, eliciting transient improvement. However, there was then an indolent decline in functional status. In February 2011, the patient reported confusion and worsening cognition. He was thromobocytopenic (138 000 ml), hyperproteinemic (9.0 g dl21) and hypergammaglobulinaemic (IgG 5065 mg dl21; reference range 700–1600), with a polyclonal gammopathy. The spleen was palpable and abdominal computerized tomography (CT) identified marked, homogeneous splenic enlargement (Fig. 1a). Cytopathology of a bone marrow specimen revealed mild hypercellularity with polytypic plasmacytosis (10 %), and no immunophenotypic or cytogenetic abnormalities. In April 2011, a positron emission tomography (PET) scan identified increased metabolic activity in the spleen and ascending aorta (Fig. 1b, c). As lymphoma was suspected, splenectomy was performed. Grossly the spleen contained small infarcts. Histopathology revealed prominent polyclonal plasmocytosis with normal B cell immunophenotype (Fig. 1d). During post operative days (POD) 5–17, the patient developed a Downloaded from www.microbiologyresearch.org by 052134 G 2013 SGM IP: 88.99.165.207 On: Thu, 11 May 2017 22:39:42 Printed in Great Britain Bartonella and splenic plasmacytosis (a) (c) (b) (d) right middle cerebral artery infarct, subsequently with left basal ganglia and focal occipital haemorrhage. During the post operative course, he developed intermittent fever and confusion. Automated blood cultures were again negative and no vegetations were observed by transoesophageal echocardiogram. Due to suspected prosthetic aortic arch graft infection, fastidious bacteria that have been associated with culture-negative endocarditis became a diagnostic consideration. The patient’s B. henselae and Bartonella quintana IgG titres (ARUP Laboratories) were 1 : 2048 and 1 : 128, respectively. On POD 28, stored formalin-fixed and paraffin-embedded splenic tissues were submitted to the Intracellular Pathogens Research Laboratory, North Carolina State University, for Bartonella species PCR. Previously, we described Bartonella spp. DNA carryover during animal necropsy, and during the subsequent processing of tissue samples (Varanat et al., 2009a). Hence, special precautions are routinely taken in our laboratory when sampling paraffin blocks to minimize the DNA cross-contamination. Using a sterile scalpel, multiple sections were sliced from formalin-fixed and from paraffin-embedded splenic tissues, after which DNA was extracted using a Qiagen DNeasy Blood and Tissue kit according to the manufacturer’s instructions. For each PCR, a negative control was processed to ensure that extraction buffers and reagents were not contaminated with Bartonella DNA. PCR amplification using broadrange 16S rDNA gene primers yielded negative results (Arosio et al., 2008). PCR targeting the 16S–23S rRNA intergenic spacer (ITS) region of the Bartonella genome was performed as previously described (Maggi et al., http://jmm.sgmjournals.org Fig. 1. Abdominal CT identified marked, homogeneous splenic enlargement (a). A PET scan identified increased metabolic activity in the anterior mediastinum/anterior wall of the ascending aorta (b) and spleen (c). Histopathology revealed prominent polyclonal plasmocytosis with normal B cell immunophenotype (d). 2005). No amplicons were obtained from the splenic tissue maintained for 28 days in formalin, whereas B. henselae DNA was amplified and successfully sequenced from three of five paraffin-embedded splenic tissue sections (Fig. 2). Presumably, long-term fixation in formalin resulted in cross-linking and fragmentation of DNA, thereby interfering with PCR amplification as compared with the short duration of fixation prior to embedding of the splenic tissue in paraffin. Beginning on POD 27, the patient was treated with doxycycline and gentamicin for 2 weeks, followed by doxycycline and rifampicin for several weeks. Due to an adverse rifampicin–warfarin interaction, rifampicin was discontinued and doxycycline monotherapy was continued for 5 months. Beginning on POD 157, oral azithromycin 250 mg once daily for 10 months was administered. Revision cardiac surgery was not pursued, taking into account the patient’s frailty and his wishes. Upon receiving antibiotics, he dramatically improved. At 8 months postdiagnosis, the B. henselae IgG titre had decreased to 1 : 128. The patient had improved remarkably, and oral azithromycin was continued. Despite administration of antibiotics for 1 year, mild headaches persisted. By June 2012, a repeat MRI was unremarkable; however, his B. henselae antibody titre had increased to 1 : 2048. Discussion Prior to splenectomy, this patient experienced a protracted illness and complex disease course that defied a definitive Downloaded from www.microbiologyresearch.org by IP: 88.99.165.207 On: Thu, 11 May 2017 22:39:42 339 N. Balakrishnan and others 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 Fig. 2. PCR of Bartonella genus and specific 16–23S internal transcribed spacer (ITS) elements on paraffin-embedded and formalin-fixed splenic tissue. Lanes: 1, 6 and 11, 1 kb molecular mass marker; 2, formalin-fixed tissue tested for Bartonella spp.; 3, paraffin-embedded tissue tested for Bartonella spp.; 4, positive control (B. henselae, 0.01 pg ml”1); 5, negative control; 7, formalin-fixed tissue tested for Bartonella koehlerae; 8, paraffinembedded tissue tested for B. koehlerae; 9, positive control (B. koehlerae, 0.01 pg ml”1); 10, negative control. diagnosis. The development of a post-operative fever, in conjunction with the presence of prosthetic implants and numerous negative pre- and post-operative blood cultures, facilitated diagnostic consideration of culture-negative endocarditis (Fournier et al., 2010). Subsequent serological and molecular testing confirmed B. henselae infection. Although fever often accompanies an acute infection with B. henselae, immunocompetent patients with chronic bacteraemia are rarely febrile. Fever was only documented in this patient in July 2010, and post-operatively in April 2011. Although they are very non-specific symptoms, malaise, fatigue, myalgia and neurocognitive abnormalities are often reported in patients with chronic Bartonella bacteraemia (Breitschwerdt et al., 2007, 2011). The clinical association between polyclonal gammopathy and chronic infection with intracellular bacteria or protozoa is well established; however, determining the infectious cause of hypergammaglobulinaemia can be challenging in some patients. Although infrequently reported to date, monoclonal and biclonal gammopathies have been reported in association with B. henselae infections (Krause et al., 2003). However, plasmacytosis in the bone marrow and the spleen, as documented in this patient, are not known to have been described before in association with B. henselae infection. Based upon repeated interpretations by veterinary pathologists, hypergammaglobulinaemia and plasma cell infiltration of bone spanning an 18-month time frame have been reported in a cat with multifocal osteomyelitis in association with Bartonella vinsonii subspecies berkhoffii bacteraemia 340 (Varanat et al., 2009b). Thus, infection with a Bartonella species should be included in the differential diagnostic consideration for patients with unexplained plasma cell infiltration, splenomegaly, hypergammaglobulinaemia and polyclonal or monoclonal gammopathy. The spleen is occasionally involved in Bartonella species infections. Typically, hypodense lesions are reported on radiographic imaging. When these areas are biopsied, one most commonly encounters necrotizing granulomas. In our patient, despite the lack of granulomatous inflammation, serology, PCR amplification and DNA sequencing results supported infection with B. henselae as a unifying diagnosis. In addition, splenic Bartonella infection has been reported in a patient following splenectomy performed for suspected malignancy (Ghez et al., 2001). Based upon this patient’s symptoms and rheumatological testing, including a positive anti-SSA, prednisone was administered for several months prior to surgical intervention. The PET scan demonstrated increased metabolic activity in the ascending aorta, which in retrospect, potentially supported localization of B. henselae organisms to this anatomical location. Previous studies have identified pre-existing valvular disease as a risk factor for the development of B. henselae endocarditis (Fournier et al., 2010). In two earlier case reports, patients developed endocarditis after therapeutic immunosuppression was initiated based upon positive anti-neutrophil antibody tests (Turner et al., 2005). Similarly, B. vinsonii subspecies berkhoffii genotype I endocarditis was reported in a dog from North Carolina after therapeutic immunosuppresion was initiated for suspected systemic lupus erythematosus, based upon positive anti-nuclear antibody reactivity (Breitschwerdt et al., 1995). Thus, it is possible that immunosuppression may facilitate B. henselae localization to heart valves or to prosthetic implants, and based upon the patient’s most recent B. henselae titre, antibiotic elimination of these bacteria may be difficult to achieve. Based upon multiple patient management factors, cardiac revision surgery was not performed to address a potentially infected bioprosthetic aortic valve or Dacron aortic arch implant. Based upon recent research observations, infections with Bartonella species represent a previously unrecognized cause of persistent bacteraemia in immunocompetent patients. Infection with a spectrum of Bartonella species is an important diagnostic consideration in patients with culture-negative endocarditis and is also occasionally encountered in patients with prosthetic valve endocarditis. Conclusion Based upon this case report, bartonellosis should be considered in patients with unexplained fatigue, myalgia, neurocognitive abnormalities, splenomegaly, hypergammaglobulinaemia and splenic or bone marrow plasmacytosis. Clinicians should consider bartonellosis as a Downloaded from www.microbiologyresearch.org by IP: 88.99.165.207 On: Thu, 11 May 2017 22:39:42 Journal of Medical Microbiology 62 Bartonella and splenic plasmacytosis differential diagnosis in an expanding number of clinical scenarios. endocarditis: a prospective study of 819 new cases. Clin Infect Dis 51, 131–140. Ghez, D., Bernard, L., Bayou, E., Bani-Sadr, F., Vallée, C. & Perronne, C. (2001). Bartonella henselae infection mimicking a splenic lymphoma. Scand J Infect Dis 33, 935–936. References Arosio, M., Nozza, F., Rizzi, M., Ruggeri, M., Casella, P., Beretta, G., Raglio, A. & Goglio, A. (2008). Evaluation of the MicroSeq 500 16S rDNA-based gene sequencing for the diagnosis of culture-negative bacterial meningitis. New Microbiol 31, 343–349. Krause, R., Auner, H. W., Daxböck, F., Mulabecirovic, A., Krejs, G. J., Wenisch, C. & Reisinger, E. C. (2003). Monoclonal and biclonal gammopathy in two patients infected with Bartonella henselae. Ann Hematol 82, 455–457. Maggi, R. G., Duncan, A. W. & Breitschwerdt, E. B. (2005). Novel Breitschwerdt, E. B., Kordick, D. L., Malarkey, D. E., Keene, B., Hadfield, T. L. & Wilson, K. (1995). Endocarditis in a dog due to chemically modified liquid medium that will support the growth of seven Bartonella species. J Clin Microbiol 43, 2651–2655. infection with a novel Bartonella subspecies. J Clin Microbiol 33, 154– 160. Turner, J. W., Pien, B. C., Ardoin, S. A., Anderson, A. M., Shieh, W. J., Zaki, S. R., Bhatnagar, J., Guarner, J., Howell, D. N. & Woods, C. W. (2005). A man with chest pain and glomerulonephritis. Lancet 365, Breitschwerdt, E. B., Maggi, R. G., Duncan, A. W., Nicholson, W. L., Hegarty, B. C. & Woods, C. W. (2007). Bartonella species in blood of 2062. immunocompetent persons with animal and arthropod contact. Emerg Infect Dis 13, 938–941. Varanat, M., Maggi, R. G., Linder, K. E., Horton, S. & Breitschwerdt, E. B. (2009a). Cross-contamination in the molecular detection of Breitschwerdt, E. B., Mascarelli, P. E., Schweickert, L. A., Maggi, R. G., Hegarty, B. C., Bradley, J. M. & Woods, C. W. (2011). Bartonella from paraffin-embedded tissues. Vet Pathol 46, 940–944. Varanat, M., Travis, A., Lee, W., Maggi, R. G., Bissett, S. A., Linder, K. E. & Breitschwerdt, E. B. (2009b). Recurrent osteomyelitis in a cat Hallucinations, sensory neuropathy, and peripheral visual deficits in a young woman infected with Bartonella koehlerae. J Clin Microbiol 49, 3415–3417. due to infection with Bartonella vinsonii subsp. berkhoffii genotype II. J Vet Intern Med 23, 1273–1277. Fournier, P. E., Thuny, F., Richet, H., Lepidi, H., Casalta, J. P., Arzouni, J. P., Maurin, M., Célard, M., Mainardi, J. L. & other authors (2010). Versalovic, J., Carroll, C. K., Funke, G., Jorgensen, J. H., Landry, M. L. & Warnock, D. W. (2011). Manual of Clinical Microbiology, pp. 786– Comprehensive diagnostic strategy for blood culture-negative 798. Washington, DC: American Society for Microbiology. http://jmm.sgmjournals.org Downloaded from www.microbiologyresearch.org by IP: 88.99.165.207 On: Thu, 11 May 2017 22:39:42 341