* Your assessment is very important for improving the workof artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download 1 In the Lower Mississippi Valley, over 300,000 acres of agricultural

Survey

Document related concepts

Transcript

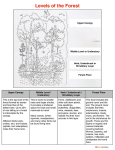

Reforestation Adjacent to Existing Forest Benefits Birds: Proximity and Vertical Structure are Important Reforestation of small, isolated tracts will likely result in mature forests that are "sink” habitats (Pulliam 1988) for birds. On these sites reproductive output does not compensate for adult mortality. This may be due to factors such as: "edge effects" (e.g., lower rates of reproductive success associated with proximity to habitat edges), "area effects" (e.g., minimum area requirements not being met by smaller tracts), or "isolation effects" (e.g., Small isolated limitations on population mixing forest tracts are and mating likely population opportunities “sinks” for birds. because of limited dispersal among tracts). Conversely, reforestation adjacent to existing forest increases contiguous forest area and thereby builds interior forest core (i.e., areas buffered from agricultural or urban habitats). Because bottomland Reforestation reforestation has historically focused adjacent to on planting relatively existing forest slow-growing tree increases species, particularly oaks [Quercus], contiguous reforested sites are forest area and usually dominated by adds to interior grasses and forbs for up to a decade forest core. following reforestation. Thus, grassland birds are the first birds to colonize reforested sites. However, because abundance and productivity of grassland birds decline as woody vegetation increases within the landscape (Johnson and Temple 1990), grassland birds may not fair well on reforested sites. Specifically, abundance and productivity of early colonizing birds may be reduced on reforested sites that abut mature forest tracts compared with isolated reforested tracts. 500 Bird detections/100 ha In the Lower Mississippi Valley, over 300,000 acres of agricultural land have been reforested in the last 10 years. Decisions on how and where to reforest are complex and usually reflect landowner objectives. However, initial decisions regarding reforestation markedly influence bird use of restored sites as young forests mature. Dick cis s e l 400 Re d-w inge d Black bird 300 200 100 0 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 Ye as post-pl an ti n g Grassland birds are first to colonize reforested sites. As woody vegetation develops on reforested sites, birds preferring shrub-scrub habitat displace grassland species (Twedt et al. 2002). Planting faster-growing trees compresses the time for colonization by shrub-scrub birds and the vertical structure of fast-growing trees attracts forest birds (Twedt and Portwood 1996). Planting next to existing forest patches has been advocated for conservation of forest dwelling birds. Hardwood plantations adjacent to existing forest tracts create "transitional edges" that mitigate the detrimental impacts associated with forest-agriculture interfaces (Lindberg et al. 1998). cropland. Reforested sites were between 2 and 15 years post-planting and were planted mostly with oaks and ash. Mature forest tracts contained trees >50 years old but differed in their silvicultural management. Bird detections/100 ha 250 RESULTS Reforested Sites – Whit e-eyed V ireo 200 Y ellow-breast ed Chat Indigo B unt ing 150 Abundance of grassland birds (e.g., Red-winged Blackbird and Dickcissel) was greater on isolated reforested tracts. Conversely, abundance of shrub-scrub birds (e.g., Yellow-breasted Chat and Indigo Bunting) was greater on reforested sites adjacent to forest. Nesting success on reforested sites was similar for each bird species regardless of their proximity to mature forest. However, Isolated tracts grassland birds tended harbored more to have low (<18%) nest grassland birds success. Thus, for most which had poor grassland birds, reforested tracts are likely nest success and likely “sink” population sinks that cannot sustain their populations. populations without immigration. 100 50 0 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 Yeas post -plant ing Shrub-scrub birds displace grassland birds as trees emerge from herbs and grasses. We assessed the effect of different reforestation strategies on bird colonization and productivity in northeast Louisiana and west-central Mississippi using reforested sites within different landscape contexts. We surveyed birds and determined nest success on both reforested and mature forest sites within different landscapes. We surveyed reforested sites that (1) abutted large tracts of mature bottomland forest, or (2) were adjacent to agricultural fields that were distant from large tracts of mature forest. We also surveyed mature forest stands that (1) were buffered by reforestation, or (2) were adjacent to agricultural Bird abundance and nest success was determined on reforested sites that (1) abutted mature forest, or (2) were next cropland and far from mature forest; and in mature forest (1) buffered by reforestation, or (2) adjacent to cropland. Table 1. Abundance (territories / 100 ha), nest success (%), and predicted habitat condition on reforested sites adjacent to and isolated from mature forest tracts. Average nesting success of all species did not differ between landscape locations (16.5%; CI90% = 15.2% – 17.7%) Abundance Isolated Adjacent Nest success Habitat condition Mourning Dove 12 7 16.8 SINK Dickcissel 106 61 17.6 SINK Red-winged Blackbird 146 63 14.2 SINK Yellow-breasted Chat 13 31 36.6 SINK Yellow-billed Cuckoo 6 7 27.9 SOURCE Orchard Oriole 11 10 34.1 SOURCE Northern Cardinal 11 15 25.3 SOURCE Indigo Bunting 13 34 31.2 SOURCE 1 SOURCE habitats have greater productivity than mortality; SINK habitats have greater mortality than productivity. Determination based on observed nest success and adult and juvenile survival estimates obtained from published literature. 2 Parasitism of nests of forest breeding birds by Brown-headed Cowbirds varied markedly among years of study. Although parasitism Female Brown-headed Cowbird lays eggs in nests did not appear to be of other forest birds. related to reforestation, cowbirds were more abundant in agricultural landscapes and parasitism rates declined with increasing distance of nests from forest edge. Because parasitism of Indigo Bunting nests declined with increasing distance from a forest edge, reforestation adjacent to existing forests will increase productivity of buntings. On the other Reforestation near hand, shrubmature forest attracted scrub birds more shrub-scrub birds had nesting success >25%. which had better nest Nesting success and were likely success for “source” populations. most these species was sufficient to maintain their populations on these sites. Thus, reforested tracts are likely population sources for shrubscrub birds. Mature Forest Sites – On mature forest tracts the amount of young reforestation in the landscape positively impacted nest survival of Acadian Flycatchers. When reforestation was widespread in the landscape, nest survival did not vary with distance to forest edge, but when little reforestation was nearby, nests further Reforestation from the forest edge acts as a survived better. buffer to Thus, reforestation appears to act as a mitigate edge buffer to mitigate effects. detrimental edge effects. More developed reforestation tracts (i.e., older or taller) appear to be more effective as buffers than are tracts dominated by grasses and forbs. 1 Parasitism Risk 0.8 0.6 0.4 0.2 0 0-100 100-200 200-300 300-400 Distance from Edge (m) Cowbird parasitism of Indigo Bunting nests declines with distance from forest edge. WHERE TO REFOREST – Daily Nest Survival 1.00 Because reforestation appears to buffer detrimental edge effects, we recommend restoration adjacent to existing forests. Similarly, because parasitism appears to decrease with distance from Reforestation near forest edge, large forest tracts placement of is more beneficial reforestation near large forest tracts than restoration is more beneficial near small forest than restoration 0.98 0.96 Low LS2 Low Average Mean LS2 High LS2 High 0.94 0.92 0.90 0-100 100-200 200-300 300-400 Distance from Edge (m) Acadian Flycatchers have increased nest survial near forest edges when a greater propoprtion (average – high) of the landscape is reforested. patches. 3 near small forest patches. However, because recruitment of naturally invading woody plants is greatest near woody edges (Twedt 2004), planting trees within 100 meters of an existing forest is likely not required to promote forest restoration. priority to less flood-prone sites such that their restoration does not increase existing forest fragmentation. The forest bird decision support model established quantitative reforestation priorities for all areas within the Mississippi Alluvial Valley. An ArcView shapefile of the model output can be viewed and downloaded at http://www.lmvjv.org/cpa_volume1.htm. Planting trees within 100 meters of existing forest is not required to promote reforestation. A forest bird decision support model is available to aid in determining the impact of placement of reforestation on forest breeding bird conservation. http://www.lmvjv.org/cpa_volume1.htm WHAT TO PLANT – Because grassland birds appear to be unproductive on reforested sites, it behooves managers to encourage succession away from colonizing grassland birds towards shrub and forest breeding birds. Restoration near existing forest stimulates colonization by shrub-scrub birds, but development of vertical forest structure within reforested sites is essential for attracting forest birds. Therefore, including a high proportion (30% – 50%) of fast-growing, early successional tree species, along with the traditional mix of slowgrowing, heavy-seeded species will encourage colonization by high priority forest birds. This Density of naturally invading trees decreases with distance form forest edge. A forest bird decision support model was constructed to aid in decision making regarding placement of reforestation sites within the landscape (Twedt et al. in review). This spatial model endeavored to provide contiguous forest blocks with interior core habitat of 2000 ha (~5000 acres) and 5000 ha (~12000 acres). Secondary emphasis was on increasing the area of existing forest core, regardless of its’ size and on increasing Trees suitable (when compatible with soils and hydrology) for planting along with heavy-seeded oaks and pecan. Many additional species are also suitable for planting. Faster-growing trees Soft-mast trees/shrubs Eastern cottonwood Red mulberry Honey locust Hawthorn spp. Black willow Dogwood spp. Sweetgum Possumhaw American sycamore Plum spp. Tulip popular American snowbell the proportion of forest within local (10 km) landscapes. Additionally, this model gave higher 4 Black locust American beautyberry Plant ≥10 tree species at a density of 302 seedlings/acre with no more than 80 seedlings/acre of any one species. Forest Breeding Bird Decisio forest restoration within the M depicted in warm colors (redrestoration, cool colors (white Water is dark blue and existin 5 Conservation: A Spatially Explicit Decision Support Model. Conservation Ecology (in review). is particularly important when restoration sites are distant from existing mature forests. Additionally, at least one species should be planted for soft-mast. Heavy-seeded oaks and pecans should be limited to 25 – 40% percent of planted seedlings. We Additional information is available from: recommend planting at least ten tree species at a combined density of 302 seedlings/acre (750 seedlings/ha) with no more than 80 seedlings/acre (200 seedlings/ha) of any single species (Twedt and Best 2004). Dr. Daniel Twedt USGS Patuxent Wildlife Research Center 2524 South Frontage Road Vicksburg, MS 39180 [email protected] REFERENCES Johnson, R. G. and S. A. Temple. 1990. Nest predation and brood parasitism of tallgrass prairie birds. Journal of Wildlife Management 54 (1):106-111. Lindberg, J.E., V.R Tolbert, A. Schiller, and J. Hanowski. 1998. Determining biomass crop management strategies to enhance habitat value for wildlife. p. 1322-1332. Bioenergy98, Madison, WI, October 4-8, 1998. Pulliam, H. R. 1988. Sources, sinks, and population regulation. American Naturalist 132:652-661. USGS Patuxent Wildlife Research Cen 12100 Beech Forest Road, Laurel, Maryla 301-497-5500 The mission of Patuxent Wildlife Research Center is to e providing the information needed to better manage the na Twedt, D. J. 2004. Stand Development on Reforested Bottomlands in the Mississippi Alluvial Valley. Plant Ecology (in press). The U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) prohibits discrimination in all its origin, sex, religion, age, disability, political beliefs, sexual orientation, and m programs.) Persons with disabilities who require alternative means for commu etc.) should contact USDA's TARGET Center at 202-720-2600 (voice and TD Twedt, D. J. and C. Best. 2004. Restoration of floodplain forests for the conservation of migratory landbirds. Ecological Restoration (in press). To file a complaint of discrimination write USDA, Director, Office of Civil R Avenue, SW, Washington, DC 20250-9410 or call 202-720-5964 (voice or TD Twedt, D. J., R. R. Wilson, J. L. Henne-Kerr, and D. A. Grosshuesch. 2002. Avian response to bottomland hardwood reforestation: The first 10 years. Restoration Ecology 10(4):645-655. Twedt, D. J. and J. Portwood. 1997. Bottomland hardwood reforestation for Neotropical migratory birds: Are we missing the forest for the trees? Wildlife Society Bulletin 25(3):647-652. Twedt, D. J., W. B. Uihlein, and A. B. Elliott. (in review). Habitat Restoration for Forest Bird 6 7