* Your assessment is very important for improving the workof artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download Arrhythmic risk stratification of post–myocardial infarction patients

Electrocardiography wikipedia , lookup

Remote ischemic conditioning wikipedia , lookup

Antihypertensive drug wikipedia , lookup

Cardiac contractility modulation wikipedia , lookup

Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy wikipedia , lookup

Coronary artery disease wikipedia , lookup

Heart arrhythmia wikipedia , lookup

Management of acute coronary syndrome wikipedia , lookup

Ventricular fibrillation wikipedia , lookup

Quantium Medical Cardiac Output wikipedia , lookup

Arrhythmogenic right ventricular dysplasia wikipedia , lookup

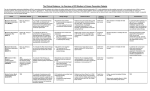

Arrhythmic risk stratification of post–myocardial infarction patients Franco Naccarella, MD, FACC,* Giovannina Lepera, MD,* and Angelo Rolli, MD† Post–myocardial infarction risk stratification, especially arrhythmic risk stratification, is an issue that has still not been wholly addressed in modern clinical cardiology. In the past 10 years, arrhythmic risk stratification has been approached mainly by evaluating frequency and complexity of premature ventricular contractions, detected on Holter monitoring, often in association with determination of percent ejection fraction. This methodology has been proven to be limited and fallacious according to the Cardiac Arrhythmia Suppression Trial I and II (CAST I,II) results, in which suppression of premature ventricular contractions or premature ventricular beats throughout by antiarrhythmic drugs resulted in an increase in both cardiac and arrhythmic mortality. Only amiodarone as an antiarrhythmic drug, as proven in the recent European Myocardial Infarct Amiodarone Trial (EMIAT) and Canadian Amiodarone Myocardial Infarction Trial (CAMIAT), was effective in reducing arrhythmic mortality without affecting cardiac mortality, in patients selected mainly because of a reduced ejection fraction, with and without premature ventricular contractions. Conversely, it is well known that β-blockers are effective in preventing sudden death in post–acute myocardial infarction (AMI) patients, thus reducing cardiac and arrhythmic mortality. Conversely, in other institutions, risk stratification in post-AMI patients has been performed by electrophysiologic study obtained, without any previous noninvasive arrhythmic risk stratification, in all post-AMI patients. In recent years, many other noninvasive electrocardiology parameters, such as late potentials (signal-averaged electrocardiography), heart rate variability, baroreflex sensitivity, and, more recently, T-wave alternance, have been shown to be useful, but they are associated with a low specificity in the noninvasive identification of patients at high risk for arrhythmic mortality. Conversely, in the Multicenter Automatic Defibrillation Implantation Trial (MADIT), electrophysiology confirmed that inducibility of ventricular tachycardia shows high specificity and a high predictive value for arrhythmic events. Nevertheless, the MADIT study population is not comparable to a cohort of consecutive patients who have recently had a myocardial infarction. In this setting, the highest risk of arrhythmic events can be observed in patients with depressed percent ejection fraction (< 35%) and in the first 6 months after AMI. Today, the most convincing approach seems to be the one combining both noninvasive risk stratification parameters (eg, premature ventricular beats > 10/h or reduced heart rate variability < 70 ms or a positive signal-averaged electrocardiogram) followed by a further arrhythmic risk stratification, obtained through electrophysiologic study. Several published and ongoing trials that utilize various arrhythmic risk stratification techniques as part of their protocol are reviewed. *Dipartimento di Cardiologia, Azienda Sanitaria della Citta’ di Bologna, Bologna, Italy; †Divisione di Cardiologia Azienda Ospedaliera di Parma, Parma, Italy Correspondence to Franco Naccarella, MD, FACC, Cardiologia Bologna, Via Mascarella 77/5, 40126 Bologna, Italy; e-mail: [email protected] Current Opinion in Cardiology 2000, 15:1–6 Abbreviations AMI ARS BEST ICD EF% EPS ICD GISSI HRV MADIT NIRS NSVT PVB acute myocardial infarction arrhythmic risk stratification Best Strategy Plus ICD Study percent ejection fraction electrophysiologic study implantable cardioverter defibrillator Gruppo Italiano per lo Studio della Sopravvivenza nell’infarto-1 Study heart rate variability Multicenter Automatic Defibrillation Implantation Trial noninvasive risk stratification nonsustained ventricular tachycardia premature ventricular beat ISSN 0268–4705 © 2000 Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, Inc. Arrhythmic risk stratification (ARS) of post–acute myocardial infarction (AMI) patients is intended to identify subgroups of patients with different risks of sudden death, using clinical parameters and data derived from noninvasive risk stratification (NIRS) or invasive procedures. Furthermore, ARS is obtained to identify the best therapeutic strategy for these patients. In fact, recent clinical studies have demonstrated that antiarrhythmic drugs, such as amiodarone, did not change total cardiac mortality, although they did decrease arrhythmic and sudden death mortality. Conversely, in the Cardiac Arrhythmia Suppression Trial, class IC and IA antiarrhythmic drugs showed an increase in both cardiac and arrhythmic mortality (CAST I,II). In the Multicenter Automatic Defibrillation Implantation Trial (MADIT) II and Antiarrhythmics Versus Implantable Defibrillators Trial studies, implantable cardioverter defibrillator (ICD) therapy was the most effective treatment for both primary and secondary prevention of sudden death, in comparison with conventional antiarrhythmic drugs. Today the most important problem is to identify patients best suited for the treatment that will be more effective in the primary prevention of sudden death. Furthermore, physicians should be able to identify patients, both at very high risk of future arrhythmic events or sudden death who are, at the same time, at low risk of nonarrhythmic mortality. Curr Opin Cardiol 2000, 15:1–6 © 2000 Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, Inc. 1 2 Arrhythmias Ventricular function Left ventricular function, measured as percent ejection fraction (EF%) is still, even in the postfibrinolytic therapy era, the most useful indicator in predicting cardiac mortality, which it predicts better than arrhythmic mortality (Table 1) [1–22]. Ventricular arrhythmias Frequent premature ventricular beats (PVB) still represent an independent prognostic factor for cardiac and arrhythmic mortality [1–22]. Premature ventricular beats are more frequently documented in patients with reduced EF% (31.8% of patients with EF < 35%). A two- to threefold increase in the mortality rate is observed in this subgroup of patients 6 months after AMI (data from the Gruppo Italiano per lo Studio della Sopravvivenza nell’Infarto-1 Study [GISSI] study) (Tables 1 and 2) [1,3•,5–22]. Nonsustained ventricular tachycardia (NSVT) is observed in 11% to 15% of post-AMI patients. The presence of NSVT is associated with a 21% mortality (34% mortality in patients with reduced EF%) in comparison with 8% mortality among patients without NSVT. The risk, independent of EF%, was more evident in the first 6 months after an AMI, but persisted over a 3-year follow-up period. In the GISSI study, NSVT was documented in 7% of patients (12.3% in those with reduced EF%). It did not affect total mortality, but only arrhythmic mortality, which was verified to be as low as 1%, in the first 6 months. Thus, the frequency and complexity of ventricular arrhythmias should still be assessed in the immediate posthospital phase of MI, only in patients with a reduced EF% (< 35%). These parameters identify patients at high risk of sudden death, who should be further stratified by electrophysiologic study (EPS), as proposed in the Best Strategy Plus ICD (BEST ICD) Study, to identify those at higher risk of sudden death (Tables 1 and 2). With this purpose, EPS has previously been used, as a single and basic method, for ARS of post-AMI patients. Conversely, some other groups have used the so-called noninvasive approach. This approach focuses mainly on Table 1. Relationship between percent ejection fraction and premature ventricular beats in the Multicenter Investigation for Limitation of Infarct Size study (MILIS) Patients PVB < 10 PVB > 10 PVB < 10 PVB > 10 EF > 40% EF < 40% EF > 40% EF < 40% Global mortality, % Sudden death mortality, % Relative risk 5 19 20 40 2 10 8 18 1 6 5 11 EF, ejection fraction; PVB, premature ventricular beats. defining the frequency and complexity of ventricular arrhythmias by electrocardiographic recording techniques (Tables 1, 2, 3, and 4). Today, a more comprehensive approach includes EPS after the risk stratification has been completed by using EF% and ambient ventricular arrhythmia identification or other NIRS parameters. Using this approach, two studies (MADIT II and BEST AICD) have been recently proposed (Figs. 1 and 2). The MADIT II study will verify whether the implantation of an ICD, in moderately high risk patients, will result in a significant reduction in overall mortality, when compared with no ICD treatment. Furthermore, a secondary objective will be to determine whether ventricular tachyarrhythmias and ventricular fibrillation, induced during implantation, are associated with more appropriate ICD discharge, during the follow-up, than is seen in noninducible ICD patients. This will also prove the utility of EPS in risk stratification of these patients. The trial is also supposed to prove, as a secondary objective, whether Holter monitoring, signal-averaged electrocardiography, heart rate variability (HRV), QT dispersion, or T-wave alternance, obtained after randomization, can identify patients with higher mortality in the conventional treatment arm. Moreover, information will be collected to determine whether NIRSidentified high-risk patients have more appropriate ICD discharges [13–18,23–27,28•,29•]. Even the BEST ICD study will try to prove the utility of a combined sequential noninvasive ARS followed by EPS (Fig. 1). The main differences between MADIT II and BEST ICD, in this respect, are as follows. In the BEST ICD study, noninvasive ARS will be limited to PVB frequency on Holter monitoring or reduced HRV (< 70 ms) or positive signal-averaged electrocardiogram, whereas, in the MADIT II study, all the noninvasive electrocardiology methods for ARS will be assessed. In the BEST ICD study, EPS will be obtained after a 2:3 randomization of patients who have been previously selected by NIRS, whereas in the MADIT II study, only patients randomly assigned to receive ICD will be tested by EPS. Successively, all patients, randomly allocated between ICD and no-ICD, will be tested by NIRS. Conversely, another study using the ICD, in both postAMI patients with coronary artery disease or patients with dilated nonischemic cardiomyopathy with heart failure and EF% less than 35%, will not use any noninvasive ARS at all (Fig. 3). In other words, clinicians think that the NIRS methods could be more valuable in ARS of post-AMI patients without congestive heart failure, in comparison with patients with congestive heart failure, Arrhythmic risk stratification of post–myocardial infarction patients Naccarella et al. 3 Table 2. Sensitivity and specificity of ventricular arrhythmias in the Betablocker Heart Attack Trial (BHAT) in predicting total mortality and sudden cardiac mortality Total mortality, % Premature ventricular beats features Sudden death mortality, % Sensitivity Specificity Sensitivity Specificity 26 33 44 14 88 82 76 94 25 34 43 16 87 80 75 94 10/h Repetitive 10/h or repetitive (either) 10/h and repetitive (both) due mainly to dilated nonischemic cardiomyopathy or minor or chronic coronary artery disease. At least, the clinical value of the NIRS methods, in association with or followed by EPS, should be more easily assessed in postAMI patients, about whom we do have more information on the usefulness of NIRS alone or primary EPS for ARS. Signal-averaged electrocardiography Late potentials have been documented in 25% to 50% of patients 1 to 4 weeks after AMI. They are predictive of spontaneous or inducible ventricular arrhythmias or sudden death (even with a low specificity in this respect), even though they have been more frequently documented in patients with reduced EF% and their prognostic significance is independent of the EF% itself [8,19,26,28•]. A very high number of false-positive results have been observed with this method. Thus, late potentials show great limitations when used alone in this clinical setting. There is substantial agreement among cardiologists to use late potentials together with other parameters or NIRS methods or in association with EPS [26,28•]. Neurovegetative tone measurements Increasingly widespread attention has been paid to the use of neurovegetative tone measurements, specifically HRV and baroreflex sensitivity in the NIRS of postAMI patients [9,10•,19–22]. HRV and total post-AMI mortality. The observed mortality was independent of other prognostic factors, and a fivefold increase in mortality has been observed in patients exhibiting an HRV of less than 50 ms. The change in HRV can be observed soon after an AMI and can be almost completely reversed 6 to 12 weeks after the episode, with some exceptions due to age and sex. The prognostic value of reduced HRV is more evident in the subgroup of patients with an EF% of less than 30% [10•]. Concurrent with this normalization, a reduction in mortality has been observed in the Cardiac Arrhythmia Pilot Study (CAPS). The new predictive value is preserved even if the evaluation is performed after 1 year and also after fibrinolytic therapy. Even HRV measurements, performed in the frequency domain, do not improve the positive predictive value of those indices, which have the same limitations as other NIRS parameters or methods. Numerous technical limitations and variability of these parameters according to sex, age, and drug interferences, EF%, AMI location, and concomitant diseases have been observed. Furthermore, HRV evaluation cannot be performed in patients with atrial fibrillation or frequent arrhythmias as premature atrial or ventricular beats. Baroreflex sensitivity In the Multicenter Postinfarction Study (MPS), a strong correlation has been found between reduced A linear relation has been proved between an increase in blood pressure and changes in the RR interval. This Table 3. Prognostic significance of inducible ventricular arrhythmias in post–acute myocardial infarction patients Study Bhandari Roy Santarelli Richards Marchlinski Breithardt Hamer Denniss Bhandari Waspe Naccarella All patients: Observations 75 150 50 165 46 132 70 403 53 50 120 1314 EPS VT VF, % Arrhythmic events, % 44 23 46 23 22 46 17 34 33 17 19 Mean value: 30.5 VF, ventricular fibrillation; VT, ventricular tachycardia; EPS, electrophysiologic study. 15 5 0 33 17 16 42 12 37 42 30 69.4 EPS negative, % 56 77 54 77 78 54 83 66 66 83 43 69.4 Arrhythmic events, % 5 1 0 3 9 4 9 4 6 9 5 5 4 Arrhythmias Table 4. Results of programmed electrical stimulation in post–acute myocardial infarction patients with nonsustained ventricular tachycardia No structural heart Observations disease, % Study Gomes Sulpizi Veltri Buxton Khasha Zheutlin Winters Klein Kowey Wilber Manolis Turitto 73 61 33 62 40 88 53 40 205 100 52 105 10 23 12 0 NSVT 27 15 42 45 20 37 25 55 64 43 40 24 0 0 912 Induced ventricular arrhythmias, % 10 46 21 24 25 7.5 VT, % VF, % 11 15 21 39 7 0 0 6 22 14 21 5 Arrhythmic events rate, % 31 11 14 25 0 12 0 40 19 0 9 14 36 Noninducible ventricular Arrhythmic arrhythmias, events rate, % % 73 39 58 31 10 6 23 12 0 0 0 0 36 63 65 7 3 6 52 6 versus versus NSVT, nonsustained ventricular tachycardia; VF, ventricular fibrillation; VT, ventricular tachycardia. relation can be changed and decreased after an AMI: its decrease correlates with an increase in the number of arrhythmic events and makes ventricular tachycardia episodes more easily inducible at EPS [10•]. Figure 1. Patient enrollment cascade of Best Strategy Plus ICD Study (BEST-ICD) EF < 35% Noninvasive testing: Holter and SAECG NSVT or VT MADIT screening The recent Autonomic Tone and Reflexes After Myocardial Infarction Study (1284 post-AMI patients, with a mean follow-up of 21 months and a total of 49 cardiac deaths) showed that reduced baroreflex sensitivity represents a prognostic parameter independent of EF% and the presence of ventricular arrhythmias with a prognostic value in addition to that of a reduced HRV. Commentary on this study confirms that a reduced baroreflex sensitivity associated with a reduced EF% (< 35%) in patients less than 65 years of age increases the relative risk of arrhythmic events to the point where no other ARS procedures would be necessary. The clinical and prognostic value of combining HRV and baroreflex PVBs ≥ 10/h or HRV (SDNN < 70 ms) or SAECG+ Metoprolol (if not initiated before) Contraindicated, not tolerated, or other exclusion criteria Figure 2. Study design of Multicenter Automatic Defibrillation Implantation Trial (MADIT) II Out Randomization 2:3 (BB + conv. therapy) Conventional strategy CAD, ≥ MI > 1 mo after AMI LV-EF ≤ 30%; age > 21 y EPS – + BB + conv. ICD + BB + therapy conv. therapy EP-guided strategy © 2000 Lippincott Williams & Wilkins BB, β-blockers; EF, ejection fraction; EP, electrophysiologic; EPS, electrophysiologic study; HRV, heart rate variability; ICD, implantable cardioverter defibrillator; MADIT, Multicenter Automatic Defibrillation Implantation Trial; NSVT, nonsustained ventricular tachycardia; PVB, premature ventricular beats; SAECG, signalaveraged electrocardiogram; SDNN, standard deviation of normal RR interval variability on electrocardiograms; VT, ventricular tachycardia. R NIRS ICD + EPS Follow-up No-ICD BB, ACE-I No AAD © 2000 Lippincott Williams & Wilkins PE: total mortality AAD, antiarrhythmic drugs; ACE-I, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors; AMI, acute myocardial infarction; BB, β-blockers; CAD, coronary artery disease; EPS, electrophysiologic study; ICD, implantable cardioverter defibrillator; LV-EF, left ventricular ejection fraction; MI, myocardial infarction; NIRS, noninvasive risk stratification. Arrhythmic risk stratification of post–myocardial infarction patients Naccarella et al. 5 Figure 3. Study design of the Sudden Cardiac Death–Heart Failure Trial (SCD-HeFT) I Conventional Rx + Placebo Double blind CAD + DCM CHF – NYHA II + III LV-EF ≤ 35% R II III Conventional Rx + Amiodarone Conventional Rx + ICD © 2000 Lippincott Williams & Wilkins (single lead, pectoral, outpatient implantation CAD, coronary artery disease; CHF, congestive heart failure; DCM, dilated nonischemic cardiomyopathy; ICD, implantable cardioverter defibrillator; LV-EF, left ventricular ejection fraction; NYHA, New York Heart Association classification. sensitivity in ARS of post-AMI patients will be strongly enhanced by the demonstration that both indices are more predictive of the occurrence or nonoccurrence of arrhythmic events, as supported by previous clinical and experimental studies. Electrophysiologic study Previous studies have demonstrated that the induction of sustained ventricular tachyarrhythmias during EPS performed after a recent AMI represents the strongest predictive factor for the occurrence of future arrhythmic events. The differences in the positive predictive value of EPS, observed in the medical literature, are mainly due to differences in the patient population, in the stimulation protocols, and particularly in the time intervals between EPS and AMI [12,23–27,28•,29•]. Furthermore, EPS is an invasive procedure that can only be performed in specially equipped hospitals and by fully trained personnel, can be associated with complications and risks, and is costly. Therefore, EPS should not be proposed as the main procedure for post-AMI ARS. Table 3 gives the results of studies using EPS in a nonselected post-AMI patient population. In Table 4, similar results of EPS, obtained in patients with NSVT, are shown. Today, it is well accepted that the most appropriate use of EPS should be in patients already selected for having positive results on NIRS. In previous studies, Pedretti et al. [22,26] showed that patients having one of certain parameters—EF% less than 40%, late potentials, frequent PVB (Lown class 4A and B)—represent 20% to 25% of all post-AMI patients. In our experience this frequency is about 10% to 15% [10•]. Furthermore, these patients showed a 30% incidence of ventricular arrhythmias in a 15-month follow-up period. In these patients, the inducibility of ventricular tachyarrhythmias during EPS has been shown to be the most effective independent variable predictive of arrhythmic events (specificity of 97% and positive predictive value of 65% of EPS vs 88% and 30%, respectively, of NIRS methods). Acknowledgments: We thank Donatella and Roberto Orlando for typing and preparing the final manuscript, tables, and figures and Alejandro Nunez for correcting the English version of the text. References and recommended reading Papers of particular interest, published within the annual period of review, have been highlighted as: • •• Of special interest Of outstanding interest 1 Naccarella F, Bracchetti D, Palmieri M, Barbato G: Arrhythmic risk stratification in post acute myocardial infarction: role of non invasive and invasive procedures: new perspective. New Trends Arrhythmias 1993, IX:41–51. 2 Salerno-Uriarte JA: La stratificazione del rischio aritmico nel postinfarto: ritorno in auge di una moda obsoleta o effettiva necessità clinica? Cardiologia 1999, 26:1169–1175. 3 • Franzosi MG, Santoro E, De Vita C, Geraci E, Lotto A, Maggioni AP, et al., on behalf of the GISSI Investigators: Ten-year follow-up of the first megatrial testing thrombolytic therapy in patients with acute myocardial infarctiom: results of the Gruppo Italiano per lo Studio della Sopravvivenza nell’Infarto-1 Study. Circulation 1998, 98:2659–2665. This article is important because the incidence and the prognostic significance of post-AMI ventricular arrhythmias changed in some way, after the widespread use of fibrinolytic therapy in post-AMI patients. 4 • Newby KH, Thompson T, Stebbins A, Topol EJ, Califf RM, Natale A, for the GUSTO Investigators: Sustained ventricular arrhythmias in patients receiving thrombolytic therapy: incidence and outcomes. Circulation 1998, 98:2567–2573. See [3•]. 5 Maggioni AP, Zuanetti G, Franzosi MG, Rovelli F, Santoro E, Staszewsky L, et al., on behalf of GISSI-2 Investigators: Prevalence and prognostic significance of ventricular arrhythmias after acute myocardial infarction in the fibrinolytic era: GISSI-2 results. Circulation 1993, 87:312–322. 6 Volpi A, De Vita C, Franzosi AM, Geraci E, Maggioni AP, Mauri F, et al., for the Ad Hoc Working Group of the Gruppo Italiano per lo Studio della Sopravvivenza nell’Infarto Miocardico (GISSI)-2 Data Base: Determinants of 6-month mortality in survivors of myocardial infarction after thrombolysis: results of the GISSI-2 data base. Circulation 1993, 88:416–429. 7 Richards DAB, Byth K, Ross DL, Uther JB: What is the best predictor of spontaneous ventricular tachycardia and sudden death after myocardial infarction? Circulation 1991, 83:756–763. 8 Kulakowski P, Malik M, Poloniecki J, Bashir Y, Odemuyiwa O, Farrell T, et al.: Frequency versus time domain analysis of signal-averaged electrocardiograms: II: identification of patients with ventricular tachycardia after myocardial infarction. J Am Coll Cardiol 1992, 20:135–143. 9 Odemuyiwa O, Malik M, Farrell T, Bashir Y, Poloniecki J, Camm J: Comparison of the predictive characteristics of heart rate variability index and left ventricular ejection fraction for all-cause mortality, arrhythmic events and sudden death after acute myocardial infarction. Am J Cardiol 1991, 68:434–439. 10 • La Rovere MT, Bigger JT Jr, Marcus FI, Mortara A, Schwartz PJ, for the ATRAMI (Autonomic Tone and Reflexes After Myocardial Infarction) Investigators: Baroreflex sensitivity and heart-rate variability in prediction of total cardiac mortality after myocardial infarction. Lancet 1998, 351:478–484. Shows the importance of reduced HRV and baroreflex sensitivity in post-AMI ARS. The association of reduced HRV and EF% less than 30% is even more powerful. 11 Martini-Rubio A, Shenasa M, Borggrefe M, Chen X, Benning F, Breithardt G: Electrophysiologic variables characterizing the induction of ventricular 6 Arrhythmias tachycardia versus ventricular fibrillation after myocardial infarction: relation between ventricular late potentials and coupling intervals for the induction of sustained ventricular tachyarrhythmias. J Am Coll Cardiol 1993, 21:1642–1631. 12 Bourcke JP, Richards DAB, Ross DL, Wallace EM, McGuire MA, Uther JB: Routine programmed electrical stimulation in survivors of acute myocardial infarction for prediction of spontaneous ventricular tachyarrhythmias during follow-up: results, optimal stimulation protocol and cost-effective screening. J Am Coll Cardiol 1991, 18:780–788. 13 Platt SB, Vijgen JM, Albrecht P, van Hare GF, Carlson MD, Rosenbaum DS: Occult T wave alternans in long QT syndrome. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol 1996, 7:144–148. 14 Rosenbaum DS, Albrecht P, Cohen RJ: Predicting sudden cardiac death from T wave alternans of the surface electrocardiogram: promise and pitfalls. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol 1996, 7:1095–1111. 15 Estes NAM III, Michaud G, Zipes DP, El-Sherif N, Venditti FJ, Rosenbaum DS, et al.: Electrical alterations during rest and exercise as predictors of vulnerability to ventricular arrhythmias. J Am Coll Cardiol 1997, 80:1314–1318. 16 Armoundas AA, Rosenbaum DS, Ruskin JN, Garan H, Cohen RJ. Prognostic significance of electrical alternans versus signal-averaged electrocardiography in predicting the outcome of electrophysiological testing and arrhythmia-free survival. Heart 1998, 80:251–256. 17 Hohnloser SH, Klingenheben T, Li YG, Zabel M, Peetermans J, Cohen RJ: T wave alternans as a predictor of recurrent ventricular tachyarrhythmias in ICD recipients: prospective comparison with conventional risk markers. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol 1998, 9:1258–1268. 18 Bigger JT Jr, for the Coronary Artery Bypass Graft (CABG) Patch Trial Investigators: Prophylactic use of implanted cardiac defibrillators in patients at high risk for ventricular arrhythmias after coronary artery bypass graft surgery. N Engl J Med 1997, 337:1569–1575. 19 Farrell TG, Bashir Y, Malik M, Poloniecki J, Bennett ED, Ward DE, Camm AJ: Risk stratification for arrhythmic events based on heart rate variability, ambulatory electrocardiographic variables and the signal averaged electrocardiogram. J Am Coll Cardiol 1991, 18:687–697. 20 Odemujiawa O, Malik M, Farrell T, Camm AJ: Comparison of the predictive characteristics of heart rate variability index and left ventricular ejection fraction for all-cause mortality, arrhythmic events and sudden death after acute myocardial infarction. Am J Cardiol 1991, 68:434–439. 21 Bigger JT, Fleiss JL, Roinitzky LM, Steinman RC: Frequency domain measures of heart period variability to assess risk late after myocardial infarction. J Am Coll Cardiol 1993, 21:729–736. 22 Pedretti R, Colombo E, Sarzi Braga S, Carù B: Effect of thrombolysis on heart rate variability and life-threatening ventricular arrhythmias in survivors of acute myocardial infarction. Int J Cardiol 1994, 23:19–26. 23 Roy D, Marchand E, Théroux P, Waters DD, Pellettier GB, Bourassa MG: Programmed ventricular stimulation in survivors of an acute myocardial infarction. Circulation 1985, 72:487–494. 24 Bourke JP, Young AA, Richards DA, Uther JB: Reduction in incidence of inducible ventricular tachycardia after myocardial infarction by treatment with streptokinase during infarct evolution. J Am Coll Cardiol 1990, 16:1703–1710. 25 Hii JTY, Traboulsi M, Mitchell LB, Wyse DG, Duff HJ, Gillis AM: Infarct artery patency predicts outcome of serial electropharmacological studies in patients with malignant ventricular tachyarrhythmias. Circulation 1993, 87:764–772. 26 Pedretti R, Etro MD, Laporta A, Braga SS, Carù B: Prediction of late arrhythmic events after acute myocardial infarction from combined use of noninvasive prognostic variables and inducibility of sustained monomorphic ventricular tachycardia. Am J Cardiol 1993, 71:1131–1141. 27 Lee KL, Buxton AE, Hafley GE, Fisher JD: EP-guided therapy reduces the risk of arrhythmic events due to the use of ICDS, but not antiarrhythmic drugs: results from MUSTT. Circulation 1999, 100(suppl I):I-80–81. 28 •• Raviele A, Bongiorni MG, Brignole M, Cappato R, Capucci A, Gaita F, et al.: Which strategy is “best” after myocardial infarction? The Beta-Blocker Strategy Plus Implantable Cardioverter Defibrillator Trial: rationale and study design. Am J Cardiol 1999, 83:104D-111D. This article represents a prospective ongoing protocol that will assess the usefulness of ICD in medium-high-risk post-AMI patients (different subgroups) selected on the basis of an increased risk of sudden death (the BEST ICD study). 29 • Klein H, Auricchio A, Reek S, Geller C: New primary prevention trials of sudden cardiac death in patients with left ventricular dysfunction: SCDHEFT and MADIT-II. Am J Cardiol 1999, 83:91D–97D. This article refers to two studies assessing the usefulness of ICD in post-AMI patients with reduced EF% (MADIT II) and in patients with congestive heart failure, New York Heart Association II and III (SCD-HeFT).