* Your assessment is very important for improving the work of artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download chapter ii literature review

Electrocardiography wikipedia , lookup

Baker Heart and Diabetes Institute wikipedia , lookup

Management of acute coronary syndrome wikipedia , lookup

Remote ischemic conditioning wikipedia , lookup

Heart failure wikipedia , lookup

Coronary artery disease wikipedia , lookup

Cardiac contractility modulation wikipedia , lookup

Antihypertensive drug wikipedia , lookup

Cardiac surgery wikipedia , lookup

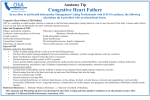

Dextro-Transposition of the great arteries wikipedia , lookup