* Your assessment is very important for improving the workof artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download Transmission Based Precautions

Health equity wikipedia , lookup

Diseases of poverty wikipedia , lookup

Viral phylodynamics wikipedia , lookup

Public health genomics wikipedia , lookup

Eradication of infectious diseases wikipedia , lookup

Patient safety wikipedia , lookup

Henipavirus wikipedia , lookup

Compartmental models in epidemiology wikipedia , lookup

Marburg virus disease wikipedia , lookup

Focal infection theory wikipedia , lookup

Hygiene hypothesis wikipedia , lookup

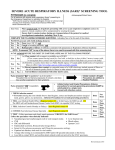

Transmission Based Precautions – Literature Reviews Droplet Precautions April 2008 Search Strategy – Droplet Precautions PRINCIPAL RESEARCH QUESTION/OBJECTIVE: What precautions can be taken to ensure patients / healthcare workers / visitors safety, from droplets which are disseminated during healthcare procedures or human activities? Search strategy for identification of studies Key Questions 1. What activities (including healthcare procedures and human activities e.g. coughing etc) can cause droplets to be disseminated from the respiratory tract? 2. What precautions can be taken to ensure patients / healthcare workers / visitors safety, from droplets which are disseminated during healthcare procedures or human activities? 3. What microorganisms are disseminated via droplets from infected / colonised patients with the potential to cause cross-transmission and cross-infection in patients / healthcare workers / visitors? 4. What type of environment(s) should be used to deliver care to patients with infections that can be disseminated via droplets? The recommendations and “Droplet Precautions – a systematic review of the evidence” are based on a collation of review and critical appraisal of the scientific evidence identified by search strategies carried out using the above key questions. Further details on each search strategy and results can be supplied on request. Period of publication Strategy key words (Full search strategies available on request) Electronic databases (tick as appropriate) 1997-2007 Droplet$ Precaution$ Patient$ Healthcare worker$ Visitor$ Healthcare Personal protective equipment Patient placement Ventilation Isolation Environment$ Patients’ rooms Care Infection Coughing Delivery of healthcare MEDLINE Science Direct CINAHL Cochrane Library British Nursing Index Disease transmission Nebulization Bacteria Viruses Respiratory tract infections Bacterial infections Virus diseases Disease reservoirs Fungi Sneezing Speaking Intubation Nasopharyngeal aspiration Respiratory tract infections Nebulisation X X X X PsycINFO EMBASE SIGLE Web of Science 1 Additional Resources (tick as appropriate) Websites (tick as appropriate) How many papers found How many papers included How many papers excluded References checked for relevant articles X Review of abstracts of professional meetings/ conferences Personal libraries consulted Experts consulted (give details if applicable) Handsearching of journals (name relevant journals e.g. Journal of Hospital Infection, Infection Control and Hospital Epidemiology) CDC X WHO Department of Health X Scottish Government HPA X Scottish Government Health Dept. 324 27 297 X X X ii) Selection criteria for inclusion of studies Sample All health and social care workers. Outcome measure(s) Interventions to minimise the spread of infections by droplets. Other inclusion criteria Any study or guidance document not reviewed within the CDC Guideline for Isolation Precautions: Preventing Transmission of Infectious Agents in Healthcare Settings 2007 Language Limitations English language only iii) Quality assessment Study quality assessment The newly published CDC Guideline for Isolation Precautions: Preventing Transmission of Infectious Agents in Healthcare Settings 2007, (Siegel et al., 2007) has been evaluated by five independent reviewers using the AGREE instrument (The AGREE Collaboration, 2001) which is designed to assess the methodological quality of guidelines. The results show the guidelines suitable for adaptation as the primary reference source for literature review and formulation of recommendations. A literature search was conducted using HPS ICT search strategies, based on agreed research questions. Identified studies, not already reviewed within the CDC guidelines, were assessed for relevance and critically appraised using SIGN-50 methodology (SIGN, 2004) to determine if additional information or considerations were required for production of transmission based precautions for healthcare settings in NHS Scotland. The methodology for grading the supporting evidence is found on the Evidence Tables including Considered Judgment Section and available from the HPS Infection Control Team on request. Category of Recommendation The recommendations have been categorised based on a combination of the system used in the CDC/HICPAC (Siegel et al., 2007) and EPIC 2 National Evidence-Based Guidelines for Preventing Healthcare-Associated Infections in NHS Hospitals in England Category IA - Strongly recommended for implementation and strongly supported by well-designed experimental, clinical, or epidemiologic studies. Category IB - Strongly recommended for implementation and supported by some experimental, clinical, or epidemiologic studies and a strong theoretical rationale. Category IC - Mandatory or required for implementation Category II - Suggested for implementation and supported by suggestive clinical or epidemiologic studies or a theoretical rationale. GPP (Good Practice Point) – Is a recommendation for best practice based on the expert opinion or practical experience of the Model Policies Steering Group No recommendation; unresolved issue. Practices for which insufficient evidence or no consensus regarding efficacy exists. 2 Data collation and analysis The SIGN 50 methodology including reviewing templates are available from the SIGN website (http://www.sign.ac.uk) The AGREE Instrument which is used for assessment and evaluation of the quality of evidence-based guidelines can be found at www.agreecollaboration.org REVIEW STATUS (delete as appropriate) DATE ISSUED REVIEW DATE CONTACT PERSON Ongoing/Complete April 2008 April 2011 Heather Murdoch 3 Table of Contents Search Strategy – Droplet Precautions .................................................................................................... 1 1 Recommendations – Droplet Precautions........................................................................................ 5 1.1 Standard Infection Control Precautions (SICP)....................................................................... 5 1.2 General principles of Transmission Based Precautions........................................................... 5 1.3 Droplet Precautions.................................................................................................................. 5 1.4 Patient Placement..................................................................................................................... 5 1.5 Personal Protective Equipment ................................................................................................ 6 1.6 Additional Precautions - potentially aerosol generating procedures ....................................... 7 1.7 Patient Transport...................................................................................................................... 7 1.8 Respiratory Hygiene/Cough Etiquette ..................................................................................... 7 2 Practical Application........................................................................................................................ 7 3 Resource Implications...................................................................................................................... 7 4 Droplet Precautions – a systematic review of the evidence............................................................. 8 General Principles of Transmission Based Precautions....................................................................... 8 Droplet Transmission........................................................................................................................... 8 Infectious agents transmissible by droplets ....................................................................................... 10 4.1 Epidemiologically important organisms ................................................................................ 10 4.2 Potential Agents of Bioterrorism ........................................................................................... 11 Droplet Precautions............................................................................................................................ 11 4.1 Spatial Separation .................................................................................................................. 11 4.2 Respiratory Hygiene / Cough Etiquette ................................................................................. 12 4.3 Hand Hygiene ........................................................................................................................ 13 4.4 Personal Protective Equipment .............................................................................................. 13 4.5 Patient Placement................................................................................................................... 15 4.6 Additional considerations ...................................................................................................... 15 Implementation of Droplet Precautions ............................................................................................. 15 Identification of Infectious Disease ................................................................................................... 15 5 Conclusions.................................................................................................................................... 16 5.1 General Principles of Transmission Based Precautions......................................................... 16 5.2 Droplet Transmission............................................................................................................. 16 5.3 Pathogens transmissible by droplets ...................................................................................... 17 5.4 Epidemiologically important organisms ................................................................................ 17 5.5 Potential Agents of Bioterrorism ........................................................................................... 17 Droplet Precautions............................................................................................................................ 18 5.6 Spatial Separation .................................................................................................................. 18 5.7 Respiratory Hygiene / Cough Etiquette ................................................................................. 18 5.8 Hand Hygiene ........................................................................................................................ 19 5.9 Personal Protective Equipment .............................................................................................. 19 5.10 Additional Precautions - aerosol generating procedures ....................................................... 20 5.11 Patient Placement................................................................................................................... 20 6 References...................................................................................................................................... 20 4 1 Recommendations – Droplet Precautions Caveat Transmission based precautions are designed to be an adjunct to standard infection control precautions. It is therefore stressed that the nine elements of standard infection control precautions must underpin all health and social care activities. It is therefore assumed for the purpose of this literature review that all standard infection control precautions are being adhered to and therefore do not require specifically addressed within this literature review and associated recommendations. More information on the standard infection control precautions including associated literature reviews is available from the Model Infection Control Policies website: http://www.hps.scot.nhs.uk/haiic/ic/modelinfectioncontrolpolicies.aspx 1.1 1.1.1 1.2 Standard Infection Control Precautions (SICP) Standard Infection Control Precautions should be adhered to for all health and social care activities. (Category 1A) General principles of Transmission Based Precautions 1.2.1 Transmission based precautions should be implemented for treatment of patients with suspected or confirmed infection which is potentially highly transmissible or as a result of a considered epidemiologically important organism. (Category 1A) (see Appendix 1 in policy) 1.2.2 The duration of transmission based precautions should be lengthened for immunosuppressed patients due to the risk of protracted shedding of viruses to avoid cross transmission. (Category 1A) 1.3 Droplet Precautions 1.3.1 Droplet precautions should be applied for patients with respiratory infections known or suspected to be transmissible by droplets (defined as >5μM) that can be generated by human activities such as sneezing and coughing as recommended in Appendix 1 in policy. (Category 1B) 1.3.2 Droplet precautions should be continued until cessation of symptoms or according to specific advice relevant to the causative organism. (see Appendix 1 in policy) (Category 1B) 1.4 Patient Placement 1.4.1 Patients with respiratory infections requiring droplet precautions should be placed in single rooms when possible. (Category II) 1.4.2 If single rooms are unavailable, cohorting should be considered based on the placing together patients with the same infection if appropriate. (Category 1B) 5 1.4.3 Patients with excessive respiratory symptoms such as coughing or production of respiratory secretions should preferentially be placed in a single room. (Category II) 1.4.4 If cohorting options with patients with same respiratory infections are not available avoid placing patients on droplet precautions with immunocompromised patients or long stay patients. (Category II) 1.4.5 Local infection control teams should be consulted for advice on individual risk assessments on patient placement decisions. (Category II) 1.4.6 Patients should be separated by at least 3 feet from each other and bed curtains can be drawn as an additional physical barrier. (Category 1B) 1.4.7 PPE must be changed and hand hygiene performed between contact with different patients on droplet precautions within the same room, even if cohorted with same respiratory infection. (Category 1B) 1.4.8 Decisions on patient placement within community settings should be individually risk assessed based on potential infection risks to other patients. (Category II) 1.4.9 Patients showing symptoms of respiratory infections requiring droplet precautions should be separated into a room or cubicle as soon as practical and given instruction on respiratory hygiene / cough etiquette precautions. (Category II) 1.5 Personal Protective Equipment 1.5.1 A surgical mask should be donned before entry into room or cubicle with patients on droplet precautions. (Category 1B) 1.5.2 The CDC guidelines and additional searched literature, do not contain specific guidance on the routine wearing of eye protection in addition to mask when working within 3 feet of patients on droplet precautions. (Unresolved Issue) 1.5.3 Certain respiratory diseases such as outbreaks of pandemic influenza or SARS have separate sources of infection control and transmission based precautions information which should be referred to: SARS http://www.hps.scot.nhs.uk/resp/severeacuterespiratorysyndrome-sars.aspx?subjectid=121 http://www.hpa.org.uk/infections/topics_az/SARS/menu.htm http://www.who.int/csr/sars/en Influenza http://www.hps.scot.nhs.uk/resp/influenza.aspx?subjectid=95 http://www.hpa.org.uk/infections/topics_az/influenza http://www.who.int/csr/disease/influenza/en 6 1.6 1.6.1 1.7 Additional Precautions - potentially aerosol generating procedures The use of suitable fit tested FFP3 respirators are required in addition to gowns, gloves and eye protection for carrying out aerosol generating procedures (e.g. intubation) on patients suffering from for example SARS. (Category II) Patient Transport 1.7.1 It is recommended that patients requiring use of droplet precautions within acute and community settings should not be moved unless necessary requirement to do so, e.g. for medical reasons. (Category II) 1.7.2 If it is necessary to move a patient on droplet precautions, the patient should be instructed on respiratory hygiene / cough etiquette and requested to wear a surgical mask if possible. (Category 1B) 1.8 Respiratory Hygiene/Cough Etiquette 1.8.1 All healthcare workers should receive specific instruction on the importance of droplet precautions for the prevention and control of transmission of infections via respiratory droplets particularly during outbreaks. (e.g. of influenza, etc) (Category 1B) 1.8.2 The duration of droplet precautions may require to be extended for specific patient populations e.g. immunosuppressed patients, due to the pattern of prolonged virus shedding. (Category 1A) A full description of the criteria used to determine if additional precautions are required are included in Appendix 1 in the policy. 2 Practical Application As the use of droplet precautions has been recommended for some time, therefore no significant change to practice should be required, however, the standards set down must be achieved. 3 Resource Implications As per current policies. All resources required for implementing droplet precautions should already be in place. 7 4 Droplet Precautions – a systematic review of the evidence Caveat Transmission based precautions are designed to be an adjunct to standard infection control precautions. It is therefore stressed that the nine elements of standard infection control precautions must underpin all health and social care activities. It is therefore assumed for the purpose of this literature review that all standard infection control precautions are being adhered to and therefore do not require specifically addressed within this literature review and associated recommendations. More information on the standard infection control precautions including associated literature reviews is available from the Model Infection Control Policies website: http://www.hps.scot.nhs.uk/haiic/ic/modelinfectioncontrolpolicies.aspx General Principles of Transmission Based Precautions Transmission Based Precautions are a set of precautions which can be implemented when patients are either suspected or known to be infected with potentially transmissible infectious agents. The precautions are defined and grouped according to route of transmission of the particular causative infectious agent. A judgment on which transmission based precautions are required is based on clinical symptoms or information on known outbreaks and any precautions applied can be altered when additional information is acquired i.e. on specific identification of particular infectious agent or regarding mode of transmission (Siegel et al., 2007) (See Appendix 1 in policy). Transmission Based Precautions should be implemented based on available clinical knowledge, while awaiting actual identification of the causative agent and should be continued either for the duration of illness or while still a risk of transmission. The duration that transmission based precautions should be continued depends on a number of factors such as patient group affected i.e. immuno-suppressed patients may required a greater duration of precautions due increased length of viral shedding etc. (Siegel et al., 2007) (See Appendix 1 in policy). Droplet Transmission Droplet transmission is defined as the transfer of large particle droplets (>5µm) from an infected respiratory tract directly to a mucosal surface or conjunctivae of another individual over a short distance. Due to the comparative large size of the particles it is accepted that droplets only travel relatively short distances through the air (Siegel et al., 2007, Collignon and Carnie, 2006, SEHD and HPS, 2005). Review of scientific evidence and available guidance has shown that infected individuals can cause respiratory droplets to be generated as a result of a number of human activities such as coughing, sneezing and even talking (Siegel et al., 2007, DH, 2007b, SEHD and HPS, 2005). A number of studies have been conducted which have confirmed transmission of microorganisms via droplets and these have been extensively reviewed within the CDC Guidelines. Studies have shown that the mucosal surfaces of the nose, eyes and occasionally the mouth are potential routes of entry to susceptible hosts by respiratory microorganisms (Siegel et al., 2007). Extensive review of scientific literature has been carried out to ascertain the maximum distance that droplets can be transmitted and this issue is to some extent unresolved. However a number of studies have shown that droplets are transmitted over short distances and this has been historically defined as 8 less than 3 feet from the patient. This distance has been used as a measure of when precautions such as use of surgical masks are required and this has been shown to be effective in prevention of transmission of microorganism via this route (Siegel et al., 2007). One small study (Ng et al., 1999) showed that visible and actual spread of respiratory droplets scattered over a distance of up to 168cm which is greater than the 3 feet limit usually considered as a sufficient distance barrier to negate requirement for droplet precautions. The distance that droplets can travel from infected respiratory tracts depends on a number of factors including, the speed, size, density and a number of additional environmental factors such as temperature, humidity etc. In addition, the activity, which resulted in the droplet expulsion from the respiratory tract, affects this distance of spread and therefore has to be considered when deciding on precautions required (Siegel et al., 2007, Collignon and Carnie, 2006). Studies show that infections transmittable via this route include the influenza virus, rhinovirus, adenovirus, Group A streptococcus and SARS- CoV (Siegel et al., 2007). Occasionally, pathogenic organisms, which are not normally transmitted via the droplet route such as Staphylococcus aureus have been shown to transmit from the respiratory tract and this, may need considered in an outbreak situation (Siegel et al., 2007). Certain healthcare procedures such as intubation, nasopharyngeal aspiration, tracheostomy care, chest physiotherapy, bronchoscopy and nebuliser therapy can cause aerosolisation of microorganisms, which usually transmit via the droplet route and therefore may require additional precautions. This has been implicated in cases of nosocomial transmission of infectious agents such as SARS- CoV to healthcare workers (Siegel et al., 2007, DH, 2007b, HPA, 2006, HPA, 2005, SEHD and HPS, 2005, WHO, 2004). A number of articles and studies were published as a result of the SARS outbreak and although most of the studies were relatively small scale due to the nature of the outbreak, a number of interesting points have been identified. One scientific study (Christian et al., 2004) described a failure of PPE which resulted in cross transmission of SARS to healthcare workers. Although this was not a controlled study it highlighted that none of the N95 respirators had been fit tested prior to carrying out aerosol generating procedures. This therefore adds to the evidence that respiratory infections transmissible via droplets can be aerosolised during certain healthcare procedures and may therefore require additional precautions, which should be properly applied. It is also noted in some studies and guidance that medical conditions such as asthma, allergic rhinitis and chronic obstructive lung disease may result in droplets from respiratory tract transmitting short distances into the immediate environment and although these patients may not be infectious, precautions should be taken (Siegel et al., 2007). Infectious agents that result in HAI are mainly from human sources although occasionally are environmental. Human sources of infection include patients but also visitors, families and healthcare workers. This can include people with active and obvious respiratory infections; those with unknown asymptomatic infections and those colonised with pathogens which are transmissible via respiratory droplets (Siegel et al., 2007). Patients in hospital or other healthcare facilities can be particularly vulnerable to infection as a result of other medical conditions and this can influence the severity of disease resulting from healthcare HAI. Certain patient populations are considered high risk such as immuno-compromised individuals, patients in ITU and Burns units etc and this should be considered when assessing potential risk posed by microorganisms which disseminate via respiratory droplets (Siegel et al., 2007). 9 The mode of transmission of microorganisms varies and there are several classes of pathogenic organisms that can disseminate via respiratory droplets. It is also reported that some pathogens can transmit by more than one route (Siegel et al., 2007). Infectious agents transmissible by droplets The new CDC Isolation Guidelines (Siegel et al., 2007) include a substantial literature review with supporting evidence, of the main pathogens transmissible by the droplet route. Microorganisms which are transmissible by this route include Bordetella pertussis, influenza virus, adenovirus, rhinovirus, Mycoplasma pneumoniae, SARS-associated coronavirus (SARS-CoV), group A streptococcus, mumps, Parvovirus, rubella and Neisseria meningitidis. Additionally there is some evidence that respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) is transmissible via droplets although the reviewed studies suggest that it is direct contact with the respiratory droplets which is the most important route of transmission of this infection (Siegel et al., 2007, Banning, 2006). In a retrospective cohort study (Gerber et al., 2001), the authors show that adenovirus has the potential to be transmitted via droplets when it presents as a respiratory infection, however it is noted that adherence to droplet and contact precautions is effective and control spread. The authors also stress the importance of swift diagnosis to ensure that the correct precautions are in place. One recently published review article (Tellier, 2006) argues that aerosol transmission of influenza A is an underestimated mode of transmission. However although interesting, this literature review has not been conducted with sufficient rigour to provide additional evidence for use in formulation of recommendations for the transmission based precautions. The findings reported within another recently published literature review, which demonstrates a rigorous approach to assessment of evidence, indicates however that influenza transmission is primarily via the droplet route and that the airborne route is not frequent enough to be considered a concern (Brankston et al., 2007). Occasionally, scientific evidence indicates that some microorganisms that are not commonly transmitted by the droplet route can be disseminated in this way. There are published studies which demonstrate the organism S. aureus being disseminated by droplets from the nose in both experimental and clinical situations, however this is generally quite rare (Siegel et al., 2007). A study (Kimura et al., 1999) showed that there was a significantly higher risk of Helicobacter pylori amongst patients residing in care homes compared to home care and that this implies the possibility of droplet spread. This paper is interesting but there is not sufficient evidence for inclusion in transmission based precautions unless further studies are published to substantiate this. In addition to the list of pathogens (See Appendix 1 in policy) known to be transmissible via droplets, there have been new and emerging diseases that have been shown to transmit via this route e.g. SARS and avian influenza. (Siegel et al., 2007, DH, 2007b, DH, 2007a, HPA, 2006, WHO, 2006b, WHO, 2006a). Additionally, evidence contained within a retrospective cohort study demonstrated high levels of SARS-CoV virus present in saliva and throat wash, which supports the transmission of SARS by oral droplets. However, the authors detected the presence of virus in cell free form and hypothesised that this could provide a possible explanation to support the potential for a degree of airborne spread (Wang et al., 2004). 4.1 Epidemiologically important organisms There is a growing list of microorganisms which are considered to epidemiologically important. This term encompasses pathogenic organisms, which can cause outbreaks within healthcare settings, 10 requiring additional methods of infection prevention and control. A number of these organisms are known to disseminate via the droplet route and include, influenza, group A streptococcus, RSV etc. The seriousness of HAI caused by any of these pathogens can be increased by the setting , i.e. the occurrence of Group A strep within a Burns unit, because of the patient population affected and the comparative severity of illness within these populations. Another feature of epidemiologically important organisms is that a number are resistant to antibiotics e.g. MRSA, VRE etc. (Siegel et al., 2007). 4.2 Potential Agents of Bioterrorism The CDC Isolation guidelines (Siegel et al., 2007) have issued an appendix and additional information on a range of microorganisms which are potentially associated with acts of bioterrorism. Review of the scientific literature shows that a number of these organisms are believed to be transmissible via the droplet route and therefore requiring implementation of droplets precautions as part of the control strategy. These organisms include Pneumonic Plague and there is some experimental evidence to show that some viral haemorrhagic fevers i.e. Ebola, may disseminate via droplets a short distance into the environment and therefore infection control advice for a case of haemorrhagic fever viruses involves implementation of droplet as well as contact precautions with additional eye protection. However in the case of a outbreak caused by deliberate release, the advice given in the present guidelines is that airborne precautions should be used due to the lack of available knowledge about the causative strain. Droplet Precautions These are a set of precautions designed to prevent cross transmission of infectious agents, which are transmissible by respiratory droplets and include the components below. 4.1 Spatial Separation It is known that droplet spread is dependant on a number of factors such as the method they are generated (e.g. coughing etc) and even on environmental factors such as temperature and humidity, however it is accepted that the spread is generally a short distance. Traditionally, an area of 3 feet around the patient has been considered as the potential zone of spread and the use of this exclusion zone has been effective in the management of outbreaks of respiratory diseases transmissible via this route (Siegel et al., 2007, DH, 2007b, SEHD and HPS, 2005, Tablan et al., 2004, WHO and IFRCRCS, 2001, Collignon and Carnie, 2006). It was recommended within the previously published “Guideline for isolation precautions in hospitals” (Garner, 1996) that a distance of 3 feet should be maintained between patients and healthcare workers/ visitors to protect from respiratory illnesses transmissible by large particle droplets generated by coughing, sneezing etc. It was also recommended within this guidance that healthcare workers should don a surgical mask when working within this distance from a patient requiring droplet precautions. However, these guidelines mentioned that locally, healthcare establishments may implement the wearing of a surgical mask on entering the room of patients infected with respiratory illness transmissible by droplets, rather than wait until within 3 feet. A number of recent studies (Ng et al., 1999, Siegel et al., 2007) have shown that a spatial separation of 3 feet may be sufficient in most occasions however there is some evidence that some droplets may travel further dependant on a number of different factors such as environmental conditions, method causing generation of respiratory droplets etc. Additionally on review of recently published studies particularly as a result of the SARS outbreak, there was a suggestion that droplets could potentially 11 spread as far as 6 feet from the source and this appeared to have resulted in nosocomial transmission to healthcare workers performing healthcare activities on infected patients. It is clear from the literature review contained within the current CDC guidance that more studies are required to elucidate the mode of droplet spread. Based on this literature review, the authors recommend that surgical masks should be donned within 6 - 10 feet of a patient or on entry to the patient’s room particularly if exposure to pathogens transmissible by droplets is possible or known (Siegel et al., 2007). Therefore, it would seem prudent to recommend that a precautionary distance of 3 feet should not be as single deciding factor for implementation of droplet precautions such as donning of a surgical mask and a practical view may need to be adopted i.e. upon entry to the patient’s room. This may be particularly sensible when dealing with newly emerging diseases of relatively unknown etiology (Siegel et al., 2007, WHO, 2004). The current review of the scientific literature, which shows that maintenance of a spatial distance of 3 feet is sufficient to prevent most cases of droplet transmission of microorganisms, and therefore substantiates inclusion of a recommendation of maintenance of this precautionary distance within communal waiting areas (Siegel et al., 2007). Recent scientific evidence included within the review section of the CDC guidance states that microorganisms transmissible only via the droplet route do not require special air handling, as they do not remain infective over long distances and this is in line with current droplet precaution guidance (Tablan et al., 2004, Collignon and Carnie, 2006, SEHD and HPS, 2005, WHO, 2004). Additional studies specifically on influenza have added weight to the evidence by demonstrating that transmission to healthcare workers was prevented by implementation of droplet precautions despite the use of positive pressure rooms which would increase the risk of cross transmission of microorganisms in one particular healthcare establishment (Siegel et al., 2007). A number of published studies are concerned with outbreaks of unknown origin and microorganisms and have shown that often, initially implemented infection control precautions can be excessive, however can be changed when more is known about the causative organism (Christian et al., 2004). This can result in infection control precautions altering over time as more information is established. 4.2 Respiratory Hygiene/Cough Etiquette The importance of swift implementation of infection control precautions was highlighted during the SARS outbreak as extensive transmission of the disease occurred to patients and staff at the triage stage or point of entry to healthcare. The importance of a strategy to deal with this has been stressed and the approach which is recommended is the introduction of respiratory hygiene / cough etiquette as part of standard infection control precautions and additional transmission based precautions (Siegel et al., 2007, SEHD and HPS, 2005). The introduction of respiratory hygiene / cough etiquette is aimed at patients and their families particularly with undiagnosed respiratory illnesses (coughing, sneezing etc) and is a fundamental component of droplet precautions. The literature suggests that application of this precaution at the point of entry into healthcare facilities reduces the transmission of respiratory infections via droplets (Siegel et al., 2007).To encourage compliance with respiratory hygiene / cough etiquette by healthcare workers, patients and visitors it is clear that education and training is required and this can be achieved by use of posters and signs describing these precautions (Siegel et al., 2007). 12 The main components of respiratory hygiene / cough etiquette, contained within the reviewed scientific literature are; covering the mouth and nose with a disposable tissue when coughing or sneezing followed by prompt disposal of the tissue in a suitable waste receptacle; use of surgical mask by the patient if possible; performance of hand hygiene following contact with respiratory secretions and separation of at least 3 feet between patients / families etc suffering from respiratory infections within communal areas such as waiting rooms etc if achievable (Siegel et al., 2007, SEHD and HPS, 2005). Furthermore, the CDC guidance states that healthcare workers should not look for fever as an indication of respiratory illness and respiratory hygiene / cough etiquette precautions should be applied as a precautionary measure in the absence of the clinical symptom of fever and even when the patient presents with chronic obstructive lung disease, asthma or other allergic conditions such as allergic rhinitis (Siegel et al., 2007). A number of scientific studies reviewed within the primary reference source substantiate the efficacy of this approach for prevention of transmission of infections via respiratory droplets. However it has been noted that wearing of masks by patients in some healthcare settings may be difficult and this may have to be considered e.g. paediatrics. (Siegel et al., 2007) 4.3 Hand Hygiene There are many studies on the role of hand hygiene within infection prevention and control and have been extensively reviewed and critiqued within the CDC Isolation Guidelines and additional literature identified from the search. It is clear from the reviews that performance of hand hygiene is vital to prevent transmission of respiratory infections transmittable via droplets within the healthcare environment (Siegel et al., 2007, Ng et al., 1999, Collignon and Carnie, 2006). The role of hand hygiene, including all aspects of the technique has been extensively reviewed within the literature review for the HPS Model Standard Infection Control Policy and for the subsequent annual review. The hand hygiene model policy also covers issues such as wearing of artificial nails and jewellery etc and should be referred to for all aspects of hand hygiene required for the standard infection control precautions which are required as a baseline for implantation of transmission based precautions (HPS, 2007). 4.4 Personal Protective Equipment Droplet transmission is defined as respiratory droplets containing infectious agents, which are transmitted a short distance into the environment directly to the mucosal surface of a recipient. Therefore one of the main precautions is to prevent access to the mucous membrane by use of Personal Protective Equipment (PPE). The evidence base would imply that due to the increased risk from infectious agents spread by droplet, contact and airborne additional PPE must be considered. This includes that even if the requirement for PPE is in line with SICPs alone it should be donned prior to entering the patient area or providing care activities in order to minimise the risk of transmission of the known/suspected infectious agent. An appendix has been attached to the policy which covers the safe donning and removal of PPE to avoid contamination. 4.4.1 Gloves Gloves are not recommended specifically for droplet precautions however they form part of the baseline standard infection control precautions required to avoid exposure from potentially harmful microorganisms that may be present in patient’s blood or body fluids such as respiratory secretions therefore are required for droplet precautions. In addition, a number of infections transmissible by droplets can also be spread by contact and therefore this potential route of transmission via 13 contaminated surfaces must be considered. The use of gloves is covered in detail within the HPS model infection control policy on PPE and associated literature reviews (HPS, 2007). 4.4.2 Gowns The use of gowns has been reviewed within the CDC guidance and within the HPS model policy on PPE. Specific advice on the use of gowns is recommended as part of standard infection control precautions to protect from exposure to potentially infected blood and body fluids such as respiratory excretions. The use of gowns is covered in detail within the HPS model infection control policy on PPE and associated literature reviews and their use as part of droplet precautions should be governed by standard infection control precautions. (Siegel et al., 2007, HPS, 2007). 4.4.3 Disposable Surgical Masks The use of a surgical face mask as PPE for the purpose of droplet precautions is reviewed within the CDC guidance (Siegel et al., 2007). In addition the HPS model policy and associated literature review (HPS, 2007) on PPE contains a review on the role of masks, as part of standard infection control precautions to protect from exposure to infectious agents via splashes or sprays of blood or body fluids such as respiratory secretions; to protect patients from exposure to potentially pathogenic organisms carried by the healthcare workers in their nasal cavity and also as part of respiratory hygiene / cough etiquette and may be used by patients to cover the nose and mouth when coughing to prevent onward transmission. The use of surgical masks is reviewed in detail within current guidance documents because exposed mucosal surfaces of the nose and mouth can provide an easy route of entry to the body for pathogenic microorganisms. Therefore it is recommended that masks and eye protection be worn for all healthcare procedures that potentially generate splashes of blood and body fluids (Siegel et al., 2007). In addition, an extensive review of the scientific and clinical evidence on the protective effect of surgical face masks has been conducted within the primary reference source. This review has shows the efficacy of the wearing of surgical face masks by healthcare workers to protect from exposure from potentially infective respiratory droplets (Siegel et al., 2007). It has been noted within the published scientific literature that certain procedures such as bronchoscopy, endotracheal intubation etc can result in the generation of aerosols and therefore additional precautions will be required to prevent transmission and it is recommended that masks and eye protection as well as gloves and gown are worn (Siegel et al., 2007). The CDC guidance (Siegel et al., 2007) contains a review of the efficacy of different mask types, however no recommendations have been made regarding this issue. 4.4.4 Eye Protection – Goggles and Face Shields The use of eye protection in addition to droplet precautions has been studied but not extensively. In fact there are only a couple of scientific reports concerning reduction of occupational transmission of RSV by the use of eye protection. However, it is not clear from these studies if other factors were involved such as the prevention of hand to eye contact rather than preventing exposure to respiratory droplets straight to the eye surface (Siegel et al., 2007). 14 4.5 Patient Placement In addition to standard infection control precautions and the instigation of droplet precautions, the use of a single room is preferable for care of patients with respiratory infections transmissible by droplets. If this option is not possible there are alternatives involving cohorting. This involves clustering of groups of patients suffering from the same disease, and the use of this method has been reviewed within recent scientific literature and current guidance (Siegel et al., 2007, Tablan et al., 2004, DH and CMO, 2003, HPA, 2005, SEHD and HPS, 2005, WHO and IFRCRCS, 2001, WHO, 2004). This type of approach is particularly relevant in the case of an outbreak e.g. seasonal or pandemic influenza, where there are potentially high numbers of people affected and requiring healthcare across all settings. In addition, there are a significant number of studies looking at evidence to support other options such as the use of spatial barriers such as distance between beds of at least 3 feet and the use of physical barriers such as bed curtains (Siegel et al., 2007, Ng et al., 1999). 4.6 Additional considerations There is an extensive review of recent scientific literature and studies, particularly as a result of the SARS outbreak which indicates that certain procedures for example intubation, nasopharyngeal aspiration, tracheostomy care, chest physiotherapy, bronchoscopy and nebuliser therapy etc, when carried out on patients suffering from respiratory illnesses considered transmissible by droplets, can result in generation of aerosols and therefore additional precautions will be required. The reviews show that use of suitable fit tested FFP3 respirators are required in addition to gowns, gloves and eye protection (Siegel et al., 2007, Collignon and Carnie, 2006, DH, 2007b, HPA, 2005, SEHD and HPS, 2005, WHO, 2006a).The literature also shows that there is a higher risk of cross transmission of respiratory infections to healthcare personnel if they are not adequately trained in the required infection control precautions or use of PPE (Siegel et al., 2007, Zamora et al., 2006, Christian et al., 2004). There is clearly a risk of contamination during the actual process of donning and removing PPE and this highlights the importance of appropriate training and instruction in the correct techniques. Implementation of Droplet Precautions Transmission of infectious respiratory diseases by droplets to patients and healthcare workers within the community can be contained by implementation of cough and respiratory etiquette and droplet precautions (Siegel et al., 2007, DH and CMO, 2003, DH, 2007a, HPA, 2006, SEHD and HPS, 2005, WHO and IFRCRCS, 2001, WHO, 2006a). A number of studies highlight the importance of staff not attending work when suffering from a respiratory illness and also emphasis the protective effect offered by staff vaccination against influenza (Siegel et al., 2007, DH, 2006). Identification of Infectious Disease To prevent transmission of various infectious diseases across healthcare settings, it is vital that the disease and causative organism is identified as rapidly as possible to enable the correct transmission based precautions to be implemented (Siegel et al., 2007, HPA, 2005). 15 5 Conclusions Caveat Transmission based precautions are designed to be an adjunct to standard infection control precautions. It is therefore stressed that the nine elements of standard infection control precautions must underpin all health and social care activities. It is therefore assumed for the purpose of this literature review that all standard infection control precautions are being adhered to and therefore do not require specifically addressed within this literature review and associated recommendations. More information on the standard infection control precautions including associated literature reviews is available from the Model Infection Control Policies website: http://www.hps.scot.nhs.uk/haiic/ic/modelinfectioncontrolpolicies.aspx 5.1 General Principles of Transmission Based Precautions 5.1.1 Transmission Based Precautions are a set of precautions which can be implemented when patients are either suspected or known to be infected with potentially transmissible infectious agents. 5.1.2 The precautions are defined and grouped according to route of transmission of the particular causative infectious agent. 5.1.3 A judgment on which transmission based precautions are required is based on clinical symptoms or information on known outbreaks and precautions applied can be altered when more specific information is received e.g. identification of causative agent by laboratory tests. 5.1.4 Transmission Based Precautions should be implemented based on clinical knowledge, while awaiting actual identification of the causative agent and should be continued either for the duration of illness or while still a risk of transmission. 5.1.5 The duration that transmission based precautions should be continued depends on a number of factors such as the patient group affected. 5.2 Droplet Transmission 5.2.1 Droplet transmission is defined as the transfer of droplets from an infected respiratory tract directly to a mucosal surface of another individual over a short distance. 5.2.2 Droplets from an infected respiratory tracts can be generated by normal human activities such as coughing, sneezing, talking and breathing. 5.2.3 Infections that can be transmitted via this route include the influenza virus, rhinovirus, adenovirus, Group A streptococcus and SARS- CoV. 5.2.4 Healthcare procedures such as intubation, nasopharyngeal aspiration, tracheostomy care, chest physiotherapy, bronchoscopy and nebuliser therapy can cause aerosolisation of microorganisms which usually transmit via droplets and therefore may require additional precautions. 16 5.2.5 5.3 Medical conditions such as asthma, allergic rhinitis and chronic obstructive lung disease may result in droplets from respiratory tract transmitting into the immediate environment, although these may not be infectious, it may be advisable to take precautions. Pathogens transmissible by droplets 5.3.1 Microorganisms which are transmissible by this route include Bordetella pertussis, influenza virus, adenovirus, rhinovirus, Mycoplasma pneumoniae, SARS-associated coronavirus (SARSCoV), group A streptococcus, mumps, Parvovirus, rubella and Neisseria meningitidis. 5.3.2 There is some evidence that respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) is transmissible via droplets although direct contact with the respiratory droplets is thought to be the most important route of infection. 5.3.3 Scientific evidence indicates that some microorganisms not commonly transmitted by droplets are occasionally disseminated in this way e.g. S. aureus has been shown to be disseminated via the droplet route from the nose in both experimental and clinical situations, although this is rare. 5.3.4 There have been new and emerging diseases which have been shown to transmit via droplets e.g. SARS. 5.4 Epidemiologically important organisms 5.4.1 There is a growing list of microorganisms which are considered to epidemiologically important, which can cause outbreaks within healthcare settings, and require additional methods of infection prevention and control. 5.4.2 A number of these organisms are known to disseminate via the droplet route and include, influenza, group A streptococcus etc. 5.4.3 The potential seriousness of HAI caused by any of these pathogens can be increased by the setting , i.e. the occurrence of group A streptococcus within a Burns unit, or because of the patient population affected and comparative severity of illness. 5.5 Potential Agents of Bioterrorism 5.5.1 There is additional information on a range of microorganisms which are potentially associated with acts of bioterrorism. 5.5.2 Review of the scientific literature shows that a number of these organisms are believed to be transmissible via the droplet route and therefore requiring droplet precautions as part of the control strategy. 5.5.3 These organisms include Pneumonic Plague and there is some experimental evidence to show that some viral haemorrhagic fevers e.g. Ebola, may disseminate via droplets, therefore infection control advice may involve implementation of droplet as well as contact precautions. 17 5.5.4 It is recommended that eye protection is worn in addition to normal droplet precautions to deal with cases of viral haemorrhagic fevers. 5.5.5 In the case of an outbreak caused by deliberate release, the advice given is that airborne precautions should be used due to the lack of available knowledge about the causative strain. Droplet Precautions These are a set of precautions designed to prevent cross transmission of infectious agents, which are transmissible by respiratory droplets and include the components below. 5.6 Spatial Separation 5.6.1 A 3 foot area around the patient has been considered as the potential zone of spread and the use of this has been effective in the management of outbreaks of respiratory diseases. 5.6.2 However, recent studies particularly resulting from the SARS outbreak have suggested that droplets could potentially spread as far as 6 feet from the source. 5.6.3 Therefore the recommendation of a precautionary distance of 3 feet should not be the single deciding factor for implementation of droplet precautions such as donning of a mask. 5.6.4 A practical view may need adopted when deciding to implement droplet precautions e.g donning a mask and it may be prudent to take precautions on entering the patient’s room, particularly when dealing with newly emerging diseases of unknown etiology. 5.7 Respiratory Hygiene/Cough Etiquette 5.7.1 Review of studies on the SARS outbreak showed the importance of swift implementation of infection control precautions as transmission to patients and staff often occurred at the triage stage or point of entry to healthcare. 5.7.2 A strategy to deal with this has been recommended which is the introduction of respiratory hygiene / cough etiquette as part of standard infection control precautions and transmission based precautions. 5.7.3 Respiratory hygiene / cough etiquette is aimed at patients with undiagnosed respiratory illnesses (coughing, sneezing etc) and is a fundamental component of droplet precautions. 5.7.4 Review of scientific literature shows that application of this precaution reduces the transmission of respiratory infections via droplets. 5.7.5 Education and training of healthcare workers, patients and visitors specifically on rationale and technique of respiratory hygiene / cough etiquette is required to promote compliance. 5.7.6 This can be achieved by the use of posters, leaflets and signs describing these precautions. 5.7.7 Respiratory hygiene/cough etiquette consists of covering the mouth and nose with disposable tissue when coughing or sneezing followed by prompt disposal in suitable waste receptacle; use of surgical masks by patient if possible; hand hygiene following contact with respiratory 18 secretions; separation of at least 3 feet between patients suffering from respiratory infections within communal areas such as waiting rooms. 5.7.8 5.8 The wearing of masks by certain patient groups may not be practical within healthcare settings such as paediatrics. Hand Hygiene 5.8.1 Many studies specifically on hand hygiene have been reviewed and critically appraised within the CDC guidance. 5.8.2 Hand hygiene is vital to prevent transmission of respiratory infections via droplets within the healthcare environment. 5.8.3 All aspects of scientific literature on hand hygiene, including technique, when, where, how and why has been extensively reviewed within the HPS model policy and associated literature reviews. 5.8.4 The HPS hand hygiene model policy should be referred to for all aspects of hand hygiene required for standard infection control or transmission based precautions. 5.9 Personal Protective Equipment 5.9.1 A main component of droplet precautions to prevent transmission of potentially infectious droplets to directly to the mucous membrane therefore the use of Personal Protective Equipment (PPE) is integral. 5.9.2 The use of disposable gloves forms part of standard infection control precautions to protect from exposure to potentially harmful microorganisms that may be present in patient’s blood or body fluids such as respiratory secretions. 5.9.3 Therefore the use of gloves is recommended within droplet precautions to protect from contact with potentially contaminated respiratory secretions and droplets. 5.9.4 Details on all aspects of the use of disposable gloves as PPE are included within HPS model infection control policy on PPE and associated literature reviews. 5.9.5 The role of gowns has been reviewed within currently available literature and guidance and their use forms part of standard infection control precautions for protection from exposure to potentially infected blood and body fluids. 5.9.6 Use of a surgical face masks as PPE for the purpose of droplet precautions has been reviewed within the CDC guidance and HPS model policy and associated literature reviews. 5.9.7 The use of surgical masks has been reviewed within current guidance documents because exposed mucosal surfaces of the nose and mouth can provide an easy route of entry to the body for pathogenic microorganisms. 5.9.8 It is therefore recommended that masks and eye protection are worn for all healthcare procedures that potentially generate splashes of blood and body fluids. 19 5.9.9 It has been shown within the primary reference source that the wearing of surgical face masks by healthcare workers protects them from exposure to potentially infective respiratory droplets, however for the purpose of transmission based precautions, PPE including masks and eye protection, if required, must be donned prior to entering he patient area or room. 5.9.10 Specific advice and instruction regarding safe donning and removal of PPE, including gowns is included in an appendix in the policy. 5.10 Additional Precautions - aerosol generating procedures 5.10.1 Recent scientific indicate that certain procedures e.g. intubation, nasopharyngeal aspiration, tracheostomy care, chest physiotherapy, bronchoscopy and nebuliser therapy etc, in patients suffering from respiratory illnesses considered transmissible only via droplets, can result in generation of aerosols and therefore additional precautions will be required. 5.10.2 The use of suitable fit tested FFP3 respirators may be required in addition to gowns, gloves and eye protection. 5.11 Patient Placement 5.11.1 The use of a single room is preferable for care of patients with respiratory infections transmissible by droplets. 5.11.2 Alternatives involving the use of cohorting are possible and involve clustering of groups of patients suffering from the same disease and this has been reviewed within recent scientific literature and current guidance. 5.11.3 This approach is particularly relevant for outbreaks i.e. seasonal or pandemic influenza. 5.11.4 In addition, there are a significant number of studies looking at evidence to support other options such as the use of spatial distance between beds of at least 3 feet and physical barriers such as bed curtains. 6 References Banning, M. (2006) Respiratory infection. Respiratory syncytial virus: disease, development and treatment, British Journal of Nursing, 15, 751-5. Brankston, G., Gitterman, L., Hirji, Z., Lemieux, C. and Gardam, M. (2007) Transmission of influenza A in human beings, The Lancet Infectious Diseases, 7, 257-65. Christian, M. D., Loutfy, M., McDonald, L. C., Martinez, K. F., Ofner, M., Wong, T., Wallington, T., Gold, W. L., Mederski, B., Green, K., Low, D. E. and Team, S. I. (2004) Possible SARS coronavirus transmission during cardiopulmonary resuscitation, Emerging Infectious Diseases, 10, 287-93. Collignon, P. J. and Carnie, J. A. (2006) Infection control and pandemic influenza, Medical Journal of Australia, 185, S54-7. Department of Health (2006) Immunisation against infectious disease - "The Green Book", DH, London. 20 Department of Health (2007a) Bird flu and pandemic influenza: What are the risks?, DH, London. Department of Health (2007b) Pandemic flu draft framework and guidance, DH, London. Department of Health and Chief Medical Officer (2003) Severe Acute Respiratory syndrome (letter gateway reference no. 1439), DH (CMO), London. Garner, J. S. (1996) Guideline for isolation precautions in hospitals. The Hospital Infection Control Practices Advisory Committee., Infection Control & Hospital Epidemiology., 17, 53-80. Gerber, S. I., Erdman, D. D., Pur, S. L., Diaz, P. S., Segreti, J., Kajon, A. E., Belkengren, R. P. and Jones, R. C. (2001) Outbreak of adenovirus genome type 7d2 infection in a pediatric chronic-care facility and tertiary-care hospital, Clinical Infectious Diseases, 32, 694-700. Health Protection Agency (2005) SARS - hospital infection control guidance, HPA, London. Health Protection Agency (2006) Health Protection Agency - Pandemic Influenza Contingency Plan, HPA, London. Health Protection Scotland (2007) Model Standard Infection Control Policies, HPS, Glasgow. Kimura, A., Matsubasa, T., Kinoshita, H., Kuriya, N., Yamashita, Y., Fujisawa, T., Terakura, H. and Shinohara, M. (1999) Helicobacter pylori seropositivity in patients with severe neurologic impairment, Brain & Development, 21, 113-7. Ng, K. S., Kumarasinghe, G. and Inglis, T. J. (1999) Dissemination of respiratory secretions during tracheal tube suctioning in an intensive care unit, Annals of the Academy of Medicine, Singapore, 28, 178-82. Scottish Executive Health Department and Health Protection Scotland (2005) Pandemic Influenza Infection Control Guidelines for use in hospitals and primary care settings, SEHD and HPS, Scotland. Siegel, J., Rhinehart, E., Jackson, M., Chiarello, L. and The Healthcare Infection Control Practices Advisory Committee (2007) Guideline for Isolation Precautions: Preventing Transmission of Infectious Agents in Healthcare Settings 2007, June 2007. Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network (2004) SIGN 50: A guideline developers' handbook, SIGN, Edinburgh. Tablan, O. C., Anderson, L. J., Besser, R., Bridges, C. and R., H. (2004) Guidelines for Preventing Healthcare Associated Pneumonia, 2003, MMWR - Morbidity & Mortality Weekly Report Recommendations and Reports, 53, 1-36. Tellier, R. (2006) Review of aerosol transmission of influenza A virus, Emerging Infectious Diseases, 12, 1657-62. The AGREE Collaboration (2001) Appraisal of Guidelines For Research & Evaluation (AGREE) Instrument, September 2001. Wang, W. K., Chen, S. Y., Liu, I. J., Chen, Y. C., Chen, H. L., Yang, C. F., Chen, P. J., Yeh, S. H., Kao, C. L., Huang, L. M., Hsueh, P. R., Wang, J. T., Sheng, W. H., Fang, C. T., Hung, C. C., Hsieh, S. M., Su, C. P., Chiang, W. C., Yang, J. Y., Lin, J. H., Hsieh, S. C., Hu, H. P., Chiang, Y. P., Yang, P. 21 C., Chang, S. C. and Hospital, S. R. G. o. t. N. T. U. N. T. U. (2004) Detection of SARS-associated coronavirus in throat wash and saliva in early diagnosis, Emerging Infectious Diseases, 10, 1213-9. World Health Organisation (2004) Practical Guidelines for Infection Control in Healthcare Facilities, WHO, Geneva. World Health Organisation (2006a) Avian Influenza, including Influenza A (H5N1), in humans: WHO Interim Infection Control Guideline for Health Care Facilities, WHO, Geneva. World Health Organisation (2006b) Infection Control Recommendations for Avian Influenza in Healthcare Facilities, WHO, Geneva. World Health Organisation and International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies (2001) Infections and Infectious Diseases - A manual for nurses and midwives in the WHO European Region, WHO and IFRC & RCS, Geneva. Zamora, J. E., Murdoch, J., Simchison, B. and Day, A. G. (2006) Contamination: a comparison of 2 personal protective systems., CMAJ Canadian Medical Association Journal., 175, 249-54. 22