* Your assessment is very important for improving the work of artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download Learning outcomes

Survey

Document related concepts

Transcript

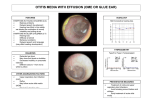

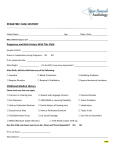

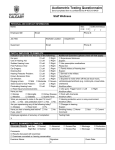

Ear examination and hearing tests Lead Lecturers: Phillipa Tostevin & Hamed Khan. Tutor Notes 2016-2017 Tutor notes – This session is linked to the first PBL case – George Marshall is a 55 year old wood machinist who is suffering from a hearing deficit caused by the high levels of noise in his work environment. SESSION PLAN: 12.00pm-12.30pm Briefing in Lecture Theatre B For Peer Tutors 12.30pm-13.30pm – Lecture Theatre B, Otoscopy lecture demonstration by ENT registrar/teaching fellow 13.30/15.30pm– Move to clinical cubicles –recap on anything that the students have queries about then spend the rest of the time observing the students and helping them develop their ear examination and hearing tests skills. 45mins Students need to practice the steps of ear examination (including otoscopy) on the manikin head first and show competent handling of the otoscope before they examine each other. The students can then practice on each other – ensure that they practice consenting each other for this procedure and that they use a new speculum each time. Please ensure that speculums are disposed of in the clinical waste. The students need to be familiar with both the wall mounted and the portable otoscopes. 45mins Students should then practice whispered voice test, Rinne’s and Weber’s on each other If there is time at the end – get the students to carry out a full examination (ear exam and hearing tests) Learning outcomes By the end of the session, students should be able to: Demonstrate competent handling of an otoscope and otoscopy technique Describe the anatomy of the outer and middle ear, identifying structures that can be seen using the otoscope Perform whispered voice and tuning fork hearing tests on a colleague Clinical relevance Otoscopy is a vital skill in many specialties but is often not practised by students as much as other skills. Consider the following scenarios: a 4 year old on the paediatric ward with a high fever, pulling at their ear a 75 year old attending his GP practice because his wife says he is deaf an anxious mother in A&E with her 2 year old child, concerned that they might have put a bead in their ear a patient admitted to the neurosurgical unit with a head injury and possible basal skull fracture; a patient in ENT outpatients, referred with possible cholesteatoma Otoscopy is an essential component in the examination of these patients. As well as being able to look in the ear, you should be able to perform the bedside hearing tests to differentiate between sensory and conductive hearing problems. These tests are not difficult, but tend to confuse and worry students – again, as with most things, if you practise, you will improve. Page 1 of 8 Ear examination and hearing tests Lead Lecturers: Phillipa Tostevin & Hamed Khan. Tutor Notes 2016-2017 Links with other learning As you can see from the paragraph above, otoscopy and hearing tests feature in many specialties. You also need to be aware of the issues that may arise in communicating with a patient with a hearing difficulty. This is significant both in gathering information during history taking, introducing yourself and explaining the examination in order to gain consent, explaining what you are doing as you go along and giving clear instructions when performing any hearing tests. What might you need to do to aid communication? Consider: background noise, your position- sit directly in front of the patient, so that they can see your lip movement clearly volume, clarity and speed of speech tone and manner non-verbal communication skills Later in the academic year during life control we will be revisiting hearing tests when you learn how to examine the cranial nerves Related Basic Sciences: Please prepare for this session. You need to know the anatomy and physiology of the ear. Where are the structures listed below located? How do they function in hearing and balance? Outer ear Helix Pinna Antihelix Tragus Concha Lobe External auditory meatus Middle ear Tympanic membrane (pars tensa, pars flaccida, attic, handle of malleus) Ossicles (malleus, incus, stapes) Mastoid air cells Eustachian tube Page 2 of 8 Ear examination and hearing tests Lead Lecturers: Phillipa Tostevin & Hamed Khan. Tutor Notes 2016-2017 Inner ear Vestibule Semicircular canals Utricle Saccules Cochlea Vestibular nerve Cochlear nerve Endolymph Perilymph General notes Remember that you will have taken a history during which it is important to establish which is the symptomatic ear and which is the “normal” ear. When talking, look at your patient and avoid looking down or covering your face. Use a normal rhythm of speech but slow down slightly, speak clearly but avoid raising your voice. It may be necessary to clarify by rephrasing or just repeating. Avoid a patronising tone or manner. During the examination it is important to remember the anatomy but note that when you look in the ear at the tympanic membrane you will not be able to see the head of the malleus and the body of the incus as these structures are normally hidden in the temporal bone. See diagrams below (reproduced with kind permission of Professor Prescott). Page 3 of 8 Ear examination and hearing tests Lead Lecturers: Phillipa Tostevin & Hamed Khan. Tutor Notes 2016-2017 Examination of the ear- STEPS Introduction & Preparation Introduce yourself fully Check the patient’s name Explain the nature and purpose of the assessment using non-technical language Offer chaperone Obtain consent Ask if the patient has any pain and if so, where it is. Clean your hands Ensure you have your patient at the correct height so you can easily examine their ears Ensure you have the correct equipment assembled and working otoscope and clean speculum 512 Hz tuning fork. Examination Start by examining the “normal” ear first. This allows you to look at the patient’s normal anatomy, compare sides, and limits risk of any infection being spread from one ear to the other. Follow the same steps for each ear: Inspect the outer ear Use the otoscope as a torch to help illuminate the outer ear. Look both in front and behind the pinna for: Scars from injury or previous surgery (a large meatus can also indicate previous surgery) Swellings or lumps Deformity Inflammation Skin condition e.g. evidence of eczema, skin lesions Hearing aids - small digital hearing aids can be very discreet Evidence of discharge Palpation Gently palpate the: Mastoid process - mastoiditis can complicate untreated otitis media Tragus Temporomandibular joint - pain from the TMJ often radiates to the ear Ask if there is any pain before gently pulling the pinna outward, back and up - pain may suggest otitis externa Otoscopy Use your right hand for their right ear and left hand for the patient’s left ear and hold the otoscope in a pen grip between your index finger and thumb. Some students (and doctors) hold the otoscope with a hammer-style grip. This is incorrect. It may feel easier initially, but gives less control, with more risk of causing pain to the patient. For this reason, it is should not be held in this manner. Gently grip the pinna and pull outward, back and up to straighten the ear canal and allow a good view of the tympanic membrane, Insert the speculum of the otoscope, resting the ulnar border of your hand on the patient’s face to help steady your hand, and to ensure that if the patient moves, then you move with them. This helps prevent trauma to the ear from unexpected movement. Use your right eye to look in the right ear and your left eye to look in the left ear. Page 4 of 8 Ear examination and hearing tests Lead Lecturers: Phillipa Tostevin & Hamed Khan. Tutor Notes 2016-2017 Inspect the external auditory meatus for - Inflammation - Eczema - Furuncles - Vesicles - Wax or debris (sometimes may completely occlude the canal. In severe otitis externa, this may require removal with microsuction) - Foreign bodies - Discharge Look at the tympanic membrane and identify the handle of the malleus and the lateral process of the malleus (a pyramidal piece of bone that lies superiorly between the handle and the head of the malleus) for orientation. Look at the colour and look for the presence of a light reflex Work your way around the pars tensa (this is the area below the lateral process of the malleus) systematically, looking for any abnormalities Then look at the pars flaccida and attic (the area above the head of the malleus. Abnormalities here are easily missed unless you actively examine this area Remove the otoscope and inspect the speculum for debris, wax, blood, or discharge Examine the other ear (use a clean speculum if necessary) Dispose of speculum in clinical waste Hearing tests Whispered voice test Use this as a quick screening test if the hearing is reported as normal First of all you need to check that the patient understands the test. Ask the patient “Can you repeat the numbers I am going to say to you?” From behind and to the side of the ear to be examined (so they cannot see your face) mask the sound in the other ear by rubbing your fingers next to the tragus and say a number at about 15cm away. Repeat with a few different numbers. Now do the test Tell the patient that you are now going to whisper some numbers and ask them to repeat them From behind and to the side of the ear to be examined (so they cannot see your face) mask the sound in the other ear by rubbing your fingers next to the tragus and whisper a number at about 60cm away (arms length). Repeat with a few different numbers If they can hear a whispered voice at this distance, their hearing is not significantly impaired Test both ears. Tuning fork tests If you identify hearing difficulty with the whispered voice test, or if the patient is complaining of hearing difficulty, you need to do the Rinne’s and Weber’s tests. The tests are based on two physiological facts: The inner ear is normally twice as sensitive to sound conducted by air as to sound conducted by bone. In the presence of a purely conductive loss the ear is subject to less environmental noise and this makes it more sensitive to bone conducted sound The principle of these tests is to compare the loudness of sound perceived purely by bone conduction with the sound perceived by air conduction. This can be used to determine whether hearing impairment is sensorineural or conductive in origin. Page 5 of 8 Ear examination and hearing tests Lead Lecturers: Phillipa Tostevin & Hamed Khan. Tutor Notes 2016-2017 Always use a 512 fork Always explain before doing the tests that you are going to use a tuning fork held in different positions in order to test their hearing and that you will be asking them to tell you where they hear the sound the loudest Always strike the prongs against a resistant but elastic object such as your elbow. This requires some practice as it can be painful! Rinne’s test Explain that you would will be holding the tuning fork in front of their ear and that you will be placing it on the bone behind the ear and that you need to know whether they can hear it loudest in front or behind. Strike the prongs of the fork and position them about 5cm from the external canal of the test ear Ask the patient “can you hear the fork?” Then place the base of the fork on the patient’s mastoid process and then position the prongs in front again. Ask the patient “which is loudest – in front or behind?” Alternate several times in front and behind so that you are clear where they are hearing it the loudest. You may need to strike the prongs again Reporting and interpreting the findings of the Rinne’s test If the sound is heard louder in front this is described as either: positive Rinne (air conduction > bone conduction) It means that the hearing in that ear is either: normal – this is because the inner ear is more sensitive to sound transmitted through the air than the sound transmitted via the bones of the base of the skull. -OR there is a sensorineural hearing loss – this is because the sound perceived by air conduction and the sound perceived by the conduction through the bones of the base of the skull are both equally diminished by the sensorineural loss resulting in the sound being still perceived as louder through the air. If the sound is heard louder behind this is described as either: negative Rinne (bone conduction > air conduction) It means that the hearing in that ear is either: conductive hearing loss >20dB - because of the difference in sensitivity between air and bone conduction, the loss needs to be >20dB for it to have diminished to such a degree that it is heard better through the bones of the base of the skull -OR occasionally you will get a false negative Rinne’s test due to a sensorineural loss –this is because the sound is transmitted to the better cochlea by bone conduction “bypassing” the bad ear altogether. Weber’s test Explain that you will be placing the base of the tuning fork on their forehead and that you need to know whether they can hear it louder in one ear or the same in both ears. Strike the prongs of the fork and place the base in the middle of the forehead. Ask “Is the sound louder in one ear, or the same in both?” Repeat if necessary to be really sure Page 6 of 8 Ear examination and hearing tests Lead Lecturers: Phillipa Tostevin & Hamed Khan. Tutor Notes 2016-2017 Reporting and interpreting the findings of the Weber’s test If the sound is heard the same in both ears this is described as sound is heard equally in both ears It means that the hearing is either: normal in both ears or there is a bilateral equivalent problem If the sound is heard louder in one ear this is described as abnormal and lateralising to either the good or the bad ear - If it lateralises to the “good” ear this means that there is a sensorineural problem in “bad” ear because the sound transmitted through the bones of the skull to both inner ears cannot be perceived as well in the bad ear because of its sensorineural problem. - If it lateralises to the “bad” ear this means that there is a conductive problem in the bad ear. This is because when the air conduction is impaired, this ear does not pick up distracting background noise. This makes it comparatively more sensitive to transmission of sound through bone than the normal ear, where the background noise is picked up. (You can mimic a conductive problem by putting your finger in your ear and do the Weber test to demonstrate this on yourself) Closure Thank your patient Clean hands Report (if not already done so) or record your findings SUMMARY OF WEBERS AND RINNES TESTS Rinnes test Louder in front = normal or sensorineural deafness Louder behind = conductive deafness (occasional false negative sensorineural) Webers test Heard equally well in both ears = normal or bilateral equivalent problem Lateralises to “good” ear = sensorineural problem in “bad” ear Lateralises to “bad” ear = conductive problem in “bad” ear Page 7 of 8 Ear examination and hearing tests Lead Lecturers: Phillipa Tostevin & Hamed Khan. Tutor Notes 2016-2017 Self directed learning During attachments in General Practice and ENT you will be examining patient’s ears. Please prepare for this in advance. Clinical reasoning: Use the otoscopy models and try to describe the changes seen in the following conditions Acute otitis media Serous effusion / secretory otitis media or “glue ear” Retracted tympanic membrane Perforation Healed perforation Tympanosclerosis When examining the ear in children, you will need to pull slightly back and down on the pinna to straighten the canal (as opposed to back and up for adults) References & Further Reading Journal articles Carney AS and Birchall JP. How to use an otoscope. sBMJ; 1995. Accessible online at http://student.bmj.com/back_issues/0795/7-otos.htm Textbooks Bickley L S, Hoekelman RA. Bates’ Guide to physical examination and history taking, 7th edition. Philadelphia: Lippincott;1999. Douglas G, Nicol F, Robertson C. Macleod’s Clinical Examination 11th edition. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone; 2005. Moore K L, Dalley A F Clinically Oriented Anatomy 5th Edition. London: Lippincott; 2006. Acknowledgements With thanks to Deborah Horton, Dr. Kerry Boardman and Philippa Tostevin for the use of their notes and to Professor Prescott for the use of the diagrams above. Page 8 of 8