* Your assessment is very important for improving the workof artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download Backgrounder: The Risk of Stroke in Atrial Fibrillation

Survey

Document related concepts

Saturated fat and cardiovascular disease wikipedia , lookup

Cardiovascular disease wikipedia , lookup

Cardiac contractility modulation wikipedia , lookup

Lutembacher's syndrome wikipedia , lookup

Coronary artery disease wikipedia , lookup

Cardiac surgery wikipedia , lookup

Management of acute coronary syndrome wikipedia , lookup

Remote ischemic conditioning wikipedia , lookup

Jatene procedure wikipedia , lookup

Myocardial infarction wikipedia , lookup

Antihypertensive drug wikipedia , lookup

Ventricular fibrillation wikipedia , lookup

Dextro-Transposition of the great arteries wikipedia , lookup

Atrial septal defect wikipedia , lookup

Transcript

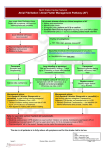

Backgrounder: The Risk of Stroke in Atrial Fibrillation (AF) What is Atrial Fibrillation (AF)? Atrial fibrillation, or AF, is the most common type of arrhythmia, a problem with the rate or rhythm of the heartbeat. During an arrhythmia, the heart can beat too fast, too slow, or with an irregular rhythm. AF occurs if rapid, disorganised electrical signals cause the heart's two upper chambers, the atria, to fibrillate.1 In atrial fibrillation, the heart does not contract as strongly as it should. This can cause blood to pool in the heart and form clots. When the blood clots dislodge, they may move to the brain, where they can become trapped in a narrow brain artery, blocking the blood flow and causing a stroke. Research suggests that over 90 percent of blood clots responsible for stroke in patients with AF originate in a pouch on the left side of the heart called left atrial appendage (LAA).2 Atrial fibrillation may be brief, with symptoms that come and go and it is possible to have an AF episode that resolves on its own. However, AF may be persistent and require treatment. Sometimes AF is permanent, and medications or other treatments cannot restore a normal heart rhythm. Risk factors for AF include3: Hemodynamic stress (i.e. heart failure or hypertension) Atrial ischemia Inflammation Non-cardiovascular respiratory causes Alcohol and drug use Endocrine disorders (i.e. diabetes) Neurologic disorders Genetic factors/Advancing age Prevalence and death rates Atrial Fibrillation affects approximately one to two percent of the general population worldwide4. Over six million Europeans suffer from this arrhythmia, and its prevalence is estimated to at least double in the next 50 years as the population ages. AF affects around 800,000 people a year in the UK5. AF is strongly age-dependent, affecting four percent of individuals older than 60 years and eight percent of persons older than 80 years. The Framingham study, a long-term, ongoing cardiovascular trial showed that approximately 25 percent of male and female individuals aged 40 years and older will develop AF during their lifetime.6 1 SH-79402-AC AUG2012 English AF in itself is an independent contributor to mortality, morbidity and impaired quality of life.7, 8 The disease is associated with a 1.5- to 1.9-fold higher risk of death, which is in part due to the strong association between AF and thromboembolic events, according to data from the Framingham heart study.9 The global burden of Atrial Fibrillation (AF) Atrial fibrillation is an increasing burden on the global healthcare system because of the numbers of patients affected, the impact of stroke, and the cost of both inpatient and outpatient therapy.10 Atrial fibrillation is associated with significant economic costs from the perspective of statutory health insurance, with the largest part of costs attributable to inpatient stays and drug usage.11 Several studies that have estimated the economic burden of AF have identified direct costs and hospitalisations as major cost drivers. In the UK and in Germany, hospital admissions have been found to represent 44 to 50 percent of direct costs and in France hospitalisations have been found to represent 60 percent of direct costs among patients with AF.12, 13, 14, 15 What is stroke? A stroke is a vascular event in the brain that causes abnormal neurological function lasting for more than 24 hours. The World Health Organisation (WHO) defines stroke as a clinical syndrome which consists of rapidly developing clinical signs of focal (or at some times global) disturbances of cerebral function. Symptoms last 24 hours or longer and can lead to death with no apparent cause other than of vascular origin.16 The most common symptom of a stroke is sudden weakness or numbness of the face, arm or leg, most often on one side of the body. Other symptoms include confusion, difficulty speaking or understanding speech, difficulty seeing with one or both eyes, difficulty walking, dizziness, loss of balance or coordination, severe headache with no known cause, fainting or unconsciousness. Stroke can be caused either by a clot obstructing the flow of blood to the brain, an ischemic stroke, or by a blood vessel rupturing and preventing blood flow to the brain, a haemorrhagic stroke. A transient ischemic attack (TIA) is caused by a temporary clot and related symptoms will go away completely within 24 hours. People who have a TIA are very likely to have a stroke in the near future. Prevalence of stroke and death rates According to the WHO, stroke is the most common cardiovascular disorder after heart disease and affects 15 million people worldwide each year. The WHO estimates that 2 SH-79402-AC AUG2012 English stroke is the number two cause of death worldwide; of the 15 million people who suffer a stroke annually, five million die and another five million are permanently disabled. About one million first strokes occur each year in the European Union (EU) and approximately 25 percent of men and 20 percent of women can expect to suffer a stroke if they live to be 85 years old.17 The total number of stroke deaths in 48 European countries is currently estimated at 1,239,000 per year.18 AF-related stroke risk AF is a major risk factor for stroke, making a person with AF five times more likely to suffer from it in comparison to the general population.19, 20 Overall, AF is estimated to be responsible for approximately 15 percent of all strokes21, 22, 23 and for 20 percent of all ischemic strokes.24 As the population ages, the global burden of AF-related stroke will continue to increase. The prevalence of stroke in AF patients older than 70 years doubles with each decade.25 Furthermore, AF-related strokes are associated with poorer outcomes than non-AFrelated strokes. This increased severity of strokes in patients with AF is thought to be related to the large size of the clots that will block a larger-sized intracranial artery depriving a larger territory of the brain of blood flow. 26 They are generally linked to higher levels of morbidity and cause higher inpatient costs than other forms of stroke.27, 28 The global burden of stroke Stroke presents a major public health challenge, with a high case fatality and a large proportion of survivors dependent on nursing and other types of care.29 The financial burden of stroke in the European Union was €38 billion in 2006, accounting for two to three percent of total healthcare expenditure in the EU.30 The average medical cost alone of stroke per patient with AF has been calculated to approximately €12.000.31 This cost is set to increase dramatically as the size of the aging population continues to rise. Reducing the risk of stroke in Atrial Fibrillation (AF) Management of AF patients is aimed at reducing symptoms and the risk of severe complications associated with AF such as stroke. The cornerstone stroke risk reduction in AF patients is oral anticoagulation therapy, with warfarin as a gold standard. In addition, non-pharmacological approaches such as closing off the left atrial appendage (LAA) offer treatment alternatives, e.g. for patients with non-valvular AF who require treatment for potential thrombus formation in the LAA and LAA and have a contraindication to anticoagulant therapy. These one-time procedures offer a permanent solution for AF patients and eliminate the need for lifelong oral anticoagulation therapy. 3 SH-79402-AC AUG2012 English Treatment Guidelines To assess the right course of treatment in AF-related stroke prophylaxis, there are several sets of international, European and country-specific guidelines, and various methods exist to categorise stroke risk. The simplest risk assessment scheme is the CHADS2 score, which is based on a point system where two points are assigned for a history of stroke or TIA and one point each is assigned for age, >75 years, a history of hypertension, diabetes, or recent cardiac failure. Treatment recommendations are based on a patient’s CHADS2 score. In addition, the 2010 European Society of Cardiology (ESC) guidelines for the management of AF also refer to the CHA2DS2-VASc score.32 It includes additional, nonmajor stroke risk factors such as age (65 to 74 years), female gender and vascular disease and complements the previous scoring system.33 It also puts extra weight on age “>75 years” as a major risk factor. In order to reduce risk of AF-related strokes, the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) recommends the initiation of anticoagulation therapy. When this therapy is appropriately used and monitored, it is highly effective, lowering stroke risk by about two thirds.34 However, current data indicates that the management of AF is still sub-optimal, with many of those receiving anticoagulation not consistently in the optimal therapeutic range.35 Also, a large percentage are not at all prescribed OACs, with most of them being over 80 years old36. In August 2012, the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) announced the inclusion of LAA closure devices like WATCHMAN™ in the revised “Guidelines for Management of Patients with Atrial Fibrillation”. The new Guidelines recommend LAA closure as a class IIb, level of evidence b, for patients with a high stroke risk and contraindications for long-term oral anticoagulation, based on existing clinical evidence such as the PROTECT AF trial. 37 Previous versions of the guidelines had already suggested that occlusion of the LAA may reduce stroke in AF patients.38 Anticoagulation therapy The goal of anticoagulant therapy is to administer the lowest possible dose of anticoagulant to reduce the risk of clot formation or expansion. Anticoagulation therapy with warfarin (Coumadin™) is widely considered the standard of care for stroke prophylaxis in patients with AF who are at high risk of stroke.39 However, the therapeutic effect of warfarin is highly unpredictable and can change due to a variety of factors, such as changes in diet or concomitant medications. As a result, safe and effective utilisation of chronic warfarin therapy requires frequent monitoring.40 The International Normalised Ratio (INR) measures the time it takes for blood to clot and compares it to an average, an important step for ensuring optimised anticoagulation 4 SH-79402-AC AUG2012 English therapy. Warfarin has a narrow therapeutic window, making it easy to over- or underdose patients, which can lead to complications, mainly bleeding.41 The FDA’s Adverse Event Reporting System indicated that warfarin is among the top 10 drugs with the largest number of serious adverse event reports submitted during the 1990 and 2000 decades42. Recent developments in the area of oral anticoagulants During the last years, new oral anticoagulants have entered the market. Such anticoagulants can be used as an alternative to warfarin to aim at stroke prevention in AF patients: Dabigatran – In the RE-LY trial, this first-to-market new oral anticoagulant showed the higher 150-mg twice-daily dose to be superior to warfarin, reducing stroke/peripheral embolic events by 34 percent and the risk of haemorrhagic stroke by 74 percent, with comparable major bleeding rates. The lower 110-mg dabigatran dose was non-inferior to warfarin in terms of efficacy, with a 20 percent reduction in major bleeding.43 Rivaroxaban – The ROCKET AF trial, reported at the 2010 American Heart Association (AHA) Scientific Sessions, rivaroxaban 20 mg once daily was shown non-inferior to warfarin in reducing all-cause stroke and non-central nervous system (CNS) embolism in AF patients, with a similar rate of major bleeding.44 Apixaban – The ARISTOTLE study showed that in patients with atrial fibrillation, apixaban was superior to warfarin in preventing stroke or systemic embolism, caused less bleeding, and resulted in lower mortality.45 While oral anticoagulants that are on the market, awaiting approval or under research offer benefits over warfarin, additional data are necessary before conclusions can be drawn on the potential for these new anticoagulant drugs to replace warfarin in patients with AF.46 In particular, patient treatment adherence and bleeding risk continue to remain major challenges of stroke risk reduction in AF patients. LAA Closure for AF-related stroke risk reduction Research shows that in over 90 percent of patients with non-valvular atrial fibrillation the stroke-causing blood clots are developed in the left atrial appendage (LAA). Currently, these patients, being at high risk of stroke, are treated with warfarin or other anticoagulant drugs. However, by closing off the source of blood clot formation, the risk of stroke may be reduced and could eliminate the need for long-term OAC therapy.47, 48 5 SH-79402-AC AUG2012 English LAA closure is a minimally-invasive procedure that usually only lasts about an hour and presents a permanent therapy option for stroke prophylaxis in patients with non-valvular AF, who require treatment for potential thrombus. In the first large-scale randomised trial, PROTECT AF, LAA closure with the WATCHMAN™ device was proven to be an alternative to warfarin. The trial demonstrated the therapeutic non-inferiority of LAA closure as an alternative to long-term warfarin in reducing the risk of stroke in non-valvular AF patients with a CHADS2 score ≥1.49 A second landmark study – the ASAP (Aspirin And Plavix®) registry – a non-randomised, prospective, multi-centre feasibility study showed a 77 percent reduction of ischemic stroke risk in high risk patients with AF who are contraindicated to warfarin. This wealth of existing data for WATCHMAN™ led to approval of expanded use of the device in Europe in August 2012, offering a treatment alternative to patients with AF, both indicated and contraindicated to anticoagulation therapy. This expands the benefits of the therapy to a wider population and especially those at higher risk than others.50, 51, 52 Currently, only two LAA closure devices have CE mark, including WATCHMAN™, with others currently still being in clinical trials. Additional Information European Society of Cardiology, www.escardio.org American Heart Association, www.heart.org American College of Cardiology, www.cardiosource.org Media Contact Mark McIntyre Public Affairs Boston Scientific Mobile: + 44 77 17300167 [email protected] References 1 National Lung Blood and Heart Institute, National Institutes of Health (NIH), July 1, 2011. Randall J. Lee, MD, PhD; Krzysztof Bartus, MD; Steven J. Yakubov, MD, Catheter-Based Left Atrial Appendage (LAA) Ligation for the Prevention of Embolic Events Arising From the LAA: Initial Experience in a Canine Model, Circ Cardiovasc Interv 2010;3;224-229. 3 Medscape: http://emedicine.medscape.com/article/151066-overview#aw2aab6b2b3aa 4 Camm JA et al. Guidelines for the Management of Atrial Fibrillation, European Heart Journal 2010, 31:2369 – 429. 5 BUPA: http://www.bupa.co.uk/individuals/health-information/directory/a/atrial-fibrillation (accessed on May 9th, 2012, at 19:37). 2 6 SH-79402-AC AUG2012 English 6 Lloyd-Jones DM, Wang TJ, Leip EP, Larson MG, Levy D, Vasan RS, et al. Lifetime risk for development of atrial fibrillation: the Framingham Heart Study. Circulation. Aug 31 2004;110(9):1042-6. 7 Thrall G, Lane D, Carroll D. et al Quality of life in patients with atrial fibrillation: a systematic review. Am J Med 2006. 119448. 8 Freestone B, Lip G Y H. Epidemiology and costs of cardiac arrhythmias. In: Lip GYH, Godtfredsen J, eds. Cardiac arrhythmias: a clinical approach Edinburgh: Mosby, 2003;3–24. 9 Wolf PA, Abbott RD, Kannel WB. Atrial fibrillation as an independent risk factor for stroke: the Framingham Study. Stroke. Aug 1991;22(8):983-8. 10 Mayo Clinic: http://www.mayoclinic.org/medicalprofs/atrial-fibrillation-therapy.html. 11 Reinhold T, Lindig C, Willich SN, Brüggenjürgen B. The costs of atrial fibrillation in patients with cardiovascular comorbidities—a longitudinal analysis of German health insurance data. Oxford Journals Medicine, EP Europace, Volume13, Issue 9 Pp. 1275-1280. 12 Coyne KS, Paramore C, Grandy S, Mercader M, Reynolds M, Zimetbaum P. Assessing the direct costs of treating non-valvular atrial fibrillation in the United States. Value Health 2006;9:348–56. 13 Le Heuzey JY, Paziaud O, Piot O, Said MA, Copie X, Lavergne T et al. Cost of care distribution in atrial fibrillation patients: the COCAF study. Am Heart J 2004;147:121–6. 14 McBride D, Mattenklotz AM, Willich SN, Bruggenjurgen B. The costs of care in atrial fibrillation and the effect of treatment modalities in Germany. Value Health 2009;12:293–301. 15 Stewart S, Murphy N, Walker A, McGuire A, McMurray JJ. Cost of an emerging epidemic: an economic analysis of atrial fibrillation in the UK. Heart 2004;90:286–92. 16 Hatano S. Experience from a multicentre stroke register: a preliminary report. Bulletin of the World Health Organisation 1976;54: 541-53. 17 Stroke Research in the European Union: ftp://ftp.cordis.europa.eu/pub/fp7/docs/stroke_bat2.pdf 18 European cardiovascular disease statistics 2008. European Heart Network, Brussels. 19 Fuster V, Ryden LE, Cannom DS, Crijns HJ, Curtis AB, Ellenbogen KA, et al. 2011 ACCF/AHA/HRS focused updates incorporated into the ACC/AHA/ESC 2006 guidelines for the management of patients with atrial fibrillation: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on practice guidelines. Circulation 2011;123(10):e269–367. 20 Roger VL, Go AS, Lloyd-Jones DM, Adams RJ, Berry JD, Brown TM, et al. Heart disease and stroke statistics–2011 update: a report from the American Heart Association [published erratum appears in Circulation 2011;123(6):e240]. Circulation 2011;123(4):e18–e209. 21 Wolf CD, Rudd AG. The Burden of Stroke White paper: Raising awareness of the global toll of strokerelated disability and death. 22 World Health Organisation. The atlas of heart disease and stroke. 23 Marmot MG, Poulter NR. Primary prevention of stroke, Lancet 1992;339:344-7. 24 Avoiding heart attacks and strokes: don’t be a victim – protect yourself. Publications of the World Health Organisation, 2005. http://www.who.int/cardiovascular_diseases/resources/cvd_report.pdf. 25 Rathore SS, Berger AK, Weinfurt KP, Schulman KA, Oetgen WJ, Gersh BJ, et al. Acute myocardial infarction complicated by atrial fibrillation in the elderly: prevalence and outcomes. Circulation. Mar 7 2000;101(9):969-74. 26 Steger C, Pratter A, Martinek-Bregel M, Avanzini M, Valentin A, Slany J et al. Stroke patients with atrial fibrillation have a worse prognosis than patients without: data from the Austrian Stroke registry. Eur Heart J 2004;25:1734–40. 27 Steger C, Pratter A, Martinek-Bregel M, Avanzini M, Valentin A, Slany J et al. Stroke patients with atrial fibrillation have a worse prognosis than patients without: data from the Austrian Stroke registry. Eur Heart J 2004;25:1734–40. 28 Ghatnekar O, Glader EL. The effect of atrial fibrillation on stroke-related inpatient costs in Sweden: a 3year analysis of registry incidence data from 2001. Value Health 2008;11:862–8. 29 Richard F. Heller, Peter Langhorne, Erica James. Improving stroke outcome: the benefits of increasing availability of technology. Bulletin of the World Health Organisation, 2000, 78: 1337–1343. 30 Allender S, Scarborough P, Peto V et al. European Cardiovascular Disease Statistics 2008 Edition. 31 Bruggenjurgen B, Rossnagel K, Roll S et al. The impact of atrial fibrillation on the cost of stroke: the Berlin acute stroke study. Value Health 2007;10:137-43. 32 Camm JA et al. Guidelines for the Management of Atrial Fibrillation, European Heat Journal 2010, 31:2369 – 429. 7 SH-79402-AC AUG2012 English 33 Lip GY, Nieuwlaat R, Pisters R, Lane DA, Crijns HJ. Refining clinical risk stratification for predicting stroke and thromboembolism in atrial fibrillation using a novel risk factor-based approach: the euro heart survey on atrial fibrillation. Chest. 2010 Feb;137(2):263-72. 34 National Health Services (NHS): http://www.improvement.nhs.uk/heart/HeartImprovementHome/AtrialFibrillation/AtrialFibrillationAnticoagula tion/tabid/129/Default.aspx. 35 National Health Services (NHS). Anticoagulation for Atrial Fibrillation Report: www.improvement.nhs.uk/heart/anticoagulation 36 Go AS et al, Warfarin Use among Ambulatory Patients with Nonvalvular Atrial Fibrillation: The AnTicoagulation and Risk Factors in Atrial Fibrillation (ATRIA) Study, Ann Intern Med. 1999 Dec 21;131(12):927-34. 37 Reddy VY et al. Safety of percutaneous left atrial appendage closure: results from the Watchman Left Atrial Appendage System for Embolic Protection in Patients with AF (PROTECT AF) clinical trial and the Continued Access Registry, Circulation 2011;123(4):417-24. 38 Camm JA et al. Guidelines for the Management of Atrial Fibrillation, European Heart Journal 2010;31:2369-2429. 39 Sullivan PW, Arant TW, Ellis SL, Ulrich H. The cost effectiveness of anticoagulation management services for patients with atrial fibrillation and at high risk of stroke in the US. Pharmacoeconomics. 2006; 24(10):1021-33. 40 Jacobson AK. Warfarin monitoring: point-of-care INR testing limitations and interpretation of the prothrombin time. Journal of Thrombosis and Thrombolysis, Volume 25, Number 1, 10-11, DOI: 10.1007/s11239-007-0098-5. 41 Landefeld CS, Beyth RJ. Anticoagulant-related bleeding: Clinical epidemiology, prediction and prevention. Am J Med. 1993;95:315-28. 42 Wysowski DK, Nourjah P, Swartz L. Bleeding Complications With Warfarin Use-A Prevalent Adverse Effect Resulting in Regulatory Action. ARCH INTERN MED/VOL 167 (NO. 13), JULY 9, 2007. 43 theheart.org: http://www.theheart.org/article/1162623.do. 44 theheart.org: http://www.theheart.org/article/1148785.do. 45 Granger CB, Alexander JH, McMurray JJV et a. for the ARISTOTLE Committees and Investigators. Apixaban versus Warfarin in Patients with Atrial Fibrillation. N Engl J Med 2011; 365:981-992September 15, 2011. 46 Altman R, Vidal HO. Battle of oral anticoagulants in the field of atrial fibrillation scrutinised from a clinical practice (the real world) perspective. Thromb J. 2011; 9: 12. 47 Alberg H. Atrial fibrillation: a study of atrial thrombus and systemic embolism in a necropsy material. Acta Med Scand. 1969;185:373–379.Medline. 48 Stoddard MF, Dawkins PR, Price CR, Ammash NM. Left atrial appendage thrombus is not uncommon in patients with acute atrial fibrillation and a recent embolic event: a transesophageal echocardiographic study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1995;25:452–459. 49 Holmes DR et al. Percutaneous closure of the left atrial appendage versus warfarin therapy for prevention of stroke in patients with atrial fibrillation: a randomised non-inferiority trial. Lancet. 2009;374:534–542. 50 The ACTIVE Steering Committee on behalf of the ACTIVE Investigators Am Heart J. 2006 Jun;151(6):1187-93. 51 Gage BF et al. Circulation. 2004;110:2287-2292. 52 Gage BF et al. JAMA. 2001 Jun 13;285(22):2864-70. 8 SH-79402-AC AUG2012 English