* Your assessment is very important for improving the workof artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download pulmonary infections - University of Yeditepe Faculty of Medicine

Compartmental models in epidemiology wikipedia , lookup

Public health genomics wikipedia , lookup

Transmission (medicine) wikipedia , lookup

Hygiene hypothesis wikipedia , lookup

Focal infection theory wikipedia , lookup

Henipavirus wikipedia , lookup

Canine distemper wikipedia , lookup

Canine parvovirus wikipedia , lookup

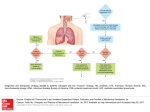

PULMONARY INFECTIONS Prof.Dr.Ferda ÖZKAN Normal Lung The lungs are constructed to carry out their cardinal function: the exchange of gases between inspired air and blood. Normal Lung The respiratory system is an outgrowth from the ventral wall of the foregut. The midline trachea develops two lateral outpocketings, the lung buds. The right lung bud eventually divides into three branches-the main bronchi-and the left into two main bronchi, thus giving rise to three lobes on the right and two on the left. The lingula on the left is the middle lobe equivalent; however, the left lung is smaller than the right. Normal Lung The right main stem bronchus is more vertical and more directly in line with the trachea than is the left. Consequently, aspirated foreign material, such as vomitus, blood, and foreign bodies, tends to enter the right lung rather than the left. Normal Lung The main right and left bronchi branch give rise to progressively smaller airways. Progressive branching of the bronchi forms bronchioles, which are distinguished from bronchi by the lack of cartilage and submucosal glands within their walls. Normal Lung Further branching of bronchioles leads to the terminal bronchioles, which are less than 2 mm in diameter. The part of the lung distal to the terminal bronchiole is called the acinus; it is approximately spherical, with a diameter of about 7 mm. Normal Lung An acinus is composed of respiratory bronchioles , which give off several alveoli from their sides. These bronchioles then proceed into the alveolar ducts, which immediately branch into alveolar sacs, the blind ends of the respiratory passages, whose walls are formed entirely of alveoli, which are the site of gas exchange. The alveoli open into the ducts through large mouths. All alveoli are open and have incomplete walls. A cluster of three to five terminal bronchioles, each with its appended acinus, is usually referred to as the pulmonary lobule. Normal Lung The entire respiratory tree, including the larynx, trachea, and bronchioles, is lined by pseudostratified, tall, columnar, ciliated epithelial cells, heavily admixed in the cartilaginous airways with mucussecreting goblet cells- except for the vocal cords, which are covered by stratified squamous epithelium, The microscopic structure of the alveolar walls The capillary endothelium lining the intertwining network of anastomosing capillaries. A basement membrane and surrounding interstitial tissue separating the endothelial cells from the alveolar lining epithelial cells. In thin portions of the alveolar septum, the basement membranes of epithelium and endothelium are fused, whereas in thicker portions, they are separated by an interstitial space (pulmonary interstitium) . - Alveolar epithelium, which contains a continuous layer of two principal cell types: flattened, platelike type I pneumocytes (or membranous pneumocytes) covering 95% of the alveolar surface and rounded type II pneumocytes. Type II cells are important for at least two reasons: (1) They are the source of pulmonary surfactant, contained in osmiophilic lamellar bodies seen with electron microscopy, and (2) they are the main cell type involved in the repair of alveolar epithelium after destruction of type I cells. Alveolar macrophages, loosely attached to the epithelial cells or lying free within the alveolar spaces, derived from blood monocytes and belonging to the mononuclear phagocyte system. Often, they are filled with carbon particles and other phagocytosed materials. The alveolar walls are not solid but are perforated by numerous pores of Kohn, which permit the passage of bacteria and exudate between adjacent alveoli Introduction Daily 10,000 liters of air – filtered Nasopharyngeal flora (during sleep) Virulent organisms. Pneumonia: Inflammation of lung. Respiratory tract infections – commonest in medical practice. Enormous morbidity & mortality. Etiology Decreased resistance - General/immune Virulent infection - Lobar pneumonia Defense Mechanisms In the normal respiratory system there are a number of important defense mechanisms that protect the lung from infection. These include: Reflex closure of the vocal cords Cough reflex Mucociliary clearance Macrophage activity and immune An increased risk of bacterial infection is associated with impairment of the defense mechanism, as in any of these clinical situations: Loss of consciousness Immunodeficiency state Pulmonary edema Neutropenia Chronic airway obstruction Viral infection. Exudate The exudate in bacterial pneumonia is typically composed of varying proportions of: edema fluid red blood cells leukocytes (principally neutrophils) fibrin The cellular exudate in acute bacterial pneumonia is in the alveolar spaces and distal bronchioles though in severe cases the major airways may also be filled with purulent secretion. Types Viral Bacterial Mycoplasmal Fungal The Pneumonia Syndromes Community-acquired acute pneumonia Streptococcus pneumonia Haemophilus influenza Moraxella catarrhalis Staphylococcus aureus Legionella pneumophilia Klebsiella Pseudomonas Community-acquired atypical pneumonia Mycoplasma Chlamydia Legionella Viruses (RSV, parainfluenza & influenza, adenovirus) Nosocomial pneumonia Aspiration pneumonia Anaerobic oral flora Amniotic fluid Gastric content Chemicals Chronic pneumonia Gram negative rods Staphlyococcus aureus Nocardia Actinomyces Granulomatous Necrotizing pneumonia Anaerobic Staphlyococcus aureus Klebsiella Streptococcus pyogens Patterns of Pulmonary infections Airway – Bronchitis/Bronchiolitis, Bronchiectasis Parenchyma Pneumonia Bronchopneumonia Lobar pneumonia Lung abscess Tuberculosis Routes of Infection Several possible routes of infection of the lung exist: Aspiration of contaminated secretions-most common Inhalation of infected airborne droplets Bacteremia Direct extension of an acute inflammatory process from an adjacent organ or structure. Etiopathogenesis Causes of bacterial pneumonia can be categorized as extrinsic and intrinsic. Extrinsic factors : infection with respiratory pathogens. Exposure to pulmonary irritants or direct pulmonary injury causes noninfectious pneumonitis. Infectious agents responsible for bacterial pneumonias include S. pneumoniae and H. influenzae; Klebsiella, Staphylococcus, and Legionella species; and gram-negative organisms. Aspiration and inhalation of aerosols containing the bacterial pathogen are the most common modes of infection. Some bacteria, such as Staphylococcus species, may spread to the lungs hematogenously. S. pneumoniae is the most common cause of bacterial pneumonia. Pneumonia from H influenzae often is associated with debilitating conditions such as asthma, COPD, smoking, and a compromised immune system. K. pneumoniae may cause a severe necrotizing lobar pneumonia in patients with chronic alcoholism, diabetes, or COPD. S. aureus pneumonia is observed in those who abuse intravenous drugs. S. aureus generally occurs in hospitalized patients and patients with prosthetic devices; it spreads hematogenously to the lungs from contaminated local sites. This pathogen also is an important cause of pneumonia following infection with influenza A. L. pneumophila infections occur either sporadically or as local outbreaks. Gram-negative pneumonias are observed in individuals who are immunocompromised or hospitalized. Causative organisms include Escherichia coli and Pseudomonas, Enterobacter, and Serratia species. Residents of chronic care facilities are at risk for gram-negative pneumonia. Intrinsic factors : related to the host's immune response, the presence of comorbidities, and other risk factors: Loss of protective reflexes allows aspiration of oropharyngeal flora into the lung. Aspiration is facilitated by altered mental status from intoxication, deranged metabolic states, neurological causes (eg, stroke), and endotracheal intubation. Local lung pathologies (eg, tumors, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease [COPD], bronchiectasis). Smoking impairs the host's defense to infection by a variety of mechanisms. Aspiration pneumonia is observed in individuals with altered sensorium (eg, seizures, alcohol intoxication, drug intoxication) or CNS impairment (eg, stroke). The stomach or oropharyngeal contents are aspirated. Complications of Pneumonia Destruction of lung tissue from infection (leading to bronchiectasis) Organization of the exudate Abscess formation Spread of the infection to the pleural cavity (empyema) Sepsis & Pyemia Respiratory failure Acute respiratory distress syndrome Superinfection with gram-negative organisms Death 1. Pneumonia 1.1. Bronchopneumonia 1.2. 1.3. Lobar pneumonia Viral (Atypical) pneumonia 1.1. Bronchopneumonia Staph, Strep, Pneumo & H. influenza Bronchopneumonia is characterized by focal areas of suppurative inflammation, in a patchy distribution, involving one or multiple lobes. Usually bilateral Lower lobes common Complications: Abscess Empyema Dissemination. The inflammatory exudate in each of the foci of involvement typically involves a small airway and surrounding alveolar spaces. Histologically The relatively small areas of involvement Focal areas of suppurative inflammation in a patchy distribution. Abscess formation. Bronchopneumonia Patchy consolidation – not limited to lobes Bronchopneumonia Bronchopneumonia Bronchopneumonia: Abscess formation Bronchopneumonia Bronchopneumonia Bronchopneumonia - Abscess formation Bronchopneumonia - CT 1.2. Lobar Pneumonia Fibrinosuppurative consolidation – whole lobe Rare (due to antibiotic treatment) ~95% - Strep. pneumoniae types 1,3,7& 2 Four stages (Laennec,1838) : Congestion & edema (1 to 2 days) Red Hepatization (2-4 days ) Gray Hepatization (4 to 8 days) Resolution (1 to 3 weeks). Congestion & Edema: This stage is characterized histologically by: vascular engorgement, intra-alveolar fluid, small numbers of neutrophils, often numerous bacteria. Grossly, the lung is heavy and hyperemic. Red hepatization: Vascular congestion persists, Extravasation of red cells into alveolar spaces, Increased numbers of neutrophils and fibrin. The filling of airspaces by the exudate leads to a gross appearance of solidification, or consolidation, of the alveolar parenchyma. A dry, granular, dark-red lung surface on gross appearance This appearance has been likened to that of the liver, hence the term "hepatization". Gray hepatization: As pneumonia progresses over 2-3 days, erythrocytes are lysed with persistence of the neutrophils and fibrin and, epithelial cells degenerate The alveoli still appear consolidated, but grossly the color is paler and the cut surface is drier. Resolution: The exudate is digested by enzymatic activity, and cleared by macrophages or by cough mechanism. Dying pneumococci release a preformed toxin, further contributing to this damage. The pneumococci are opsonized by leukocytes and begin to be cleared. Resolution results in the formation of jellylike yellowish-colored exudates. Absorption of these exudates is remarkably efficient, with little organization or permanent scaring. Lobar Pneumonia Lobar Pneumonia – Gray hepatization Strep. Pneumoniae Pneumonia Streptococcus pneumoniae produces few toxins. It causes diseases by its capacity to replicate in host tissues. The presence of a capsule allows an escape from phagocytosis, resulting in an intense inflammatory response in hosts who are immunologically naive. Colonization of the oropharynx by bacterial adherence to human pharyngeal cells is the usual first step. The alternative pathway of the complement is first activated. Anticapsular antibodies are effective in providing protection against pneumococcal infection. They appear 5-8 days after the onset of infection. By this time, fever usually disappears in the absence of treatment. Natural immunity follows infections as well as colonization. Conditions that predispose the patient to pneumococcal infection Defective antibody formation Agammaglobulinemia and hypogammaglobulinemia, multiple myeloma, chronic lymphocytic leukemia, lymphoma, and HIV infection Defective complement (C1 to C4) Defective splenic function Asplenia and splenectomy Chronic diseases Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, cirrhosis of the liver, and alcoholism Acute viral respiratory infections Post–influenza virus Pneumonia: The absence of predisposing factors is rare in pneumococcal pneumonia affecting elderly children, teenagers, and adults younger than 60 years. Meningitis: Predisposing factors include head trauma, cerebrospinal fluid leak, and respiratory tract infection. Pneumonia: Complications Pleural effusions Abscess Empyema. Meningitis (if present) Cranial nerve palsies (III, VI, VII, VIII) usually disappear within a few weeks. Vasculitis and cerebral infarction Approximately 10% of infants and children are left with persistent unilateral or bilateral sensory hearing loss. epilepsy, and mental retardation. Obstructive hydrocephalus Subdural empyema. 1.3. Atypical pneumonia (Interstitial pneumonia) Primary atypical pneumonia denotes the moderate amount of sputum, no physical findings of consolidation, moderate elevation of white cell count lack of alveolar exudate 1.3. Atypical pneumonia (Interstitial pneumonia) The etiologic agent in children: Virus (62%) Bacteria (53%) Both viral and bacterial pathogens-mixed infection (30%). The etiologic agent in adult: Bacteria (40%) Virus (11%). Mycoplasma infections are common among children and young adults. They occur sporadically or local epidemics in closed communities. Viral pneumonia can vary from a mild illness to a life-threatening disease with severe hypoxemia. Adults frequently are infected with both bacterial and viral pathogens; therefore, differentiating viral disease from bacterial disease may be impossible. Patients with the greatest risk for severe disease: Immunocompromised patients, Chronic illnesses. Nosocomial pneumonias: Adenovirus, Influenza A and B, Parainfluenza, RSV. Viruses are divided into categories depending on whether the pneumonia they cause is a primary manifestation or part of a multisystem syndrome of disease. Pneumonia as a primary manifestation influenza virus types A and B, RSV, adenovirus, parainfluenza virus, rhinovirus, hantavirus, CMV. Pneumonia as part of a multisystem syndrome Paramyxovirus species (measles), varicella-zoster virus, Epstein-Barr virus, CMV, herpes simplex virus Pathology Bilateral/unilateral involvement, Patchy lesions, Inflammatory infiltration confined within the walls, with: Edema Mononuclear cells (lympho, histio, plasma) In severe cases: Diffuse alvolar damage Hyaline membranes) Respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) infection Manifests primarily as bronchiolitis and/or viral pneumonia, Peak incidence of occurrence is observed at age 2-8 months. Reinfection with RSV occurs at all ages (limited to the URT). RSV bronchiolitis in the first year of life is one of the most important risk factors for the subsequent development of asthma. Risk for severe RSV infection: less than six weeks of age, infants with a history of prematurity, those with congenital heart disease, chronic lung conditions or immunodeficiency. Others: lower socioeconomic status, crowded living conditions, exposure to passive cigarette smoking avoidance of breast feeding. Respiratory viruses damage the respiratory tract stimulate the host to release multiple humoral factors, histamine, leukotriene C4, and virus-specific immunoglobulin E in RSV infection and bradykinin, interleukin-1, interleukin-6, and interleukin-8 in rhinovirus infections. RSV infections can also alter bacterial colonization patterns, increase bacterial adherence to respiratory epithelium, reduce mucociliary clearance, and alter bacterial phagocytosis by host cells. Lung RSV Pneumonia Influenza virus The most common cause of viral pneumonia in adults. Three serotypes of influenza virus exist: A, B, and C. Influenza type A is the serotype most frequently responsible for major epidemics and pandemics; it is the most frequent cause of viral pneumonia in adults. Influenza type A can alter surface antigens and infect livestock; perhaps, this ability accounts for its ability to create a reservoir for infection and cause epidemics in humans. Influenza type B cause illness, which usually is seen in relatively closed populations such as boarding schools. Influenza type C is less common and occurs as sporadic cases. Parainfluenza virus Parainfluenza infection occurs early in life and may cause pneumonia. Infection later in life is usually mild. Four antigenically distinct serotypes of the virus exist; however, types 1, 2, and 3 cause more severe disease than that of type 4. Parainfluenza viruses are second in importance to only RSV in causing lower respiratory tract disease in children and pneumonia and bronchiolitis in infants younger than 6 months. Adenovirus Type 7 viruses can cause bronchiolitis and pneumonia in infants. Types 4 and 7 viruses are responsible for outbreaks of respiratory disease in military recruits. Studies of atypical pneumonia in military personnel have shown that adenovirus is the etiology in as many as 40% of cases. Severe adenovirus pneumonia may occur in infants, immunocompromised patients, and rarely, healthy adults. Paramyxovirus Causing disease in unimmunized children and adults. Immunity to measles (rubeola) is maintained throughout one's lifetime. Pneumonia occurs in 5% of measles cases, with death from measles in 1 per 1,000 patients. Most deaths are due to pneumonia. CMV An extremely important cause of pneumonia in immunocompromised patients. Reactivation of latent infection is almost universal in transplant recipients and individuals infected with the human immunodeficiency virus. Additionally, CMV infection is immunosuppressive as well, causing further immunocompromise in these patients. The virus has been found in the cervix and in human milk, semen, and blood products. In cancer patients receiving allogenic bone marrow transplants, CMV pneumonia has a prevalence of 15% and a mortality rate of 85%. Varicella-zoster virus: Herpes simplex virus: In immunocompromised children/adults. Pneumonia may develop from primary infection or reactivation. Epstein-Barr virus: Pneumonia as a complication of mononucleosis is very uncommon. The virus can cause pneumonia in the absence of mononucleosis. Complications: Respiratory failure Pulmonary fibrosis Noncardiogenic pulmonary edema Superimposed bacterial infection Adult respiratory distress syndrome Reye syndrome Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome SARS First appeared in 2002 in China Coronavirus After incubation period of 2-10 days patients develop dry cough, malasie, myalgias, fever and chills 10% die of disease no specific treatment Can be detected by PCR or antibodies The lungs of the patients show diffuse alveolar damage and multinucleated giant cells Chronic Pneumonia Chronic pneumonia is most often a localized lesion in the immunocompetent patient, with or without regional lymph node involvement. There is granulomatous infection, which may be due to -bacteria M. Tuberculosis -fungi H.capsulatum, Blastomycosis, coccidioides Chronic Pneumonia Fungal pneumonia Endemic fungal pathogens (eg, Histoplasma capsulatum, Coccidioides immitis, Blastomyces dermatitidis, Paracoccidioides brasiliensis) cause infection in both healthy and immunocompromised host. Opportunistic fungal organisms (eg, Candida species, Aspergillus species, Mucor species, Cryptococcus neoformans) tend to cause pneumonia in patients with congenital or acquired defects in their host defenses. Etiology Workers or farmers with heavy exposure to bird, bat, or rodent droppings and other animal excreta. C. immitis, because of its virulence, also is a threat among laboratory personnel working with this fungus. Conditions that predispose patients to any of the opportunistic fungal pathogens are as follows: Acute leukemia or lymphoma during myeloablative chemotherapy Bone marrow transplantation Solid organ transplantation on immunosuppressive treatment Prolonged corticosteroid therapy AIDS Prolonged neutropenia from various causes Congenital immune deficiency syndromes. Histologic Findings: Caseating or necrotizing granulomas with intracellular organisms inside macrophages (eg, H capsulatum, C immitis) Fungal hyphae in Aspergillus and Mucor species Intracellular yeast organisms in Candida species. Complications: Blood vessel invasion (Dissemination and sepsis) Pulmonary hemoptysis, infarction, myocardial infarction, cerebral emboli, cerebral infarction, or blindness. Dissemimnation to other sites (brain, meninges, skin, liver, spleen, kidneys, adrenals, heart, eyes). Other complications Bronchopleural or tracheoesophageal fistulas Chronic pulmonary symptoms Mediastinal fibrosis (histoplasmosis) Broncholithiasis (histoplasmosis) Pericarditis and other rheumatologic symptoms. Tuberculosis Pulmonary infection with Mycobacterium tuberculosis is acquired as a result of inhaling the tuberculosis bacillus suspended in the aerosolized sputum coughed up by an infected individual with "open" tuberculosis. Two phases of this disease occur: Primary tuberculosis By definition, this infection occurs in an individual not previously exposed and sensitized to tubercle bacilli. Secondary (reactivation) tuberculosis By definition, this is tuberculosis which becomes clinically evident in an individual already sensitized to the tubercle bacillus. Primary Tuberculosis The sequence of events in primary infection typically involves: inhalation of infected airborne droplet particle size (approximately 3 microns) favors deep inhalation and retention of the organism the bacilli tend to locate in the subpleural midzone of lung the earliest radiographic appearance is an illdefined localized "atypical" pneumonia after a brief acute inflammatory reaction associated with a neutrophilic response, the bacilli invoke granuloma formation. By 2 to 8 weeks, the pneumonic focus becomes a more defined radiographic opaque single spheroidal lesion Ghon focus. In Non Immunized individuals (Children) Primary Tuberculosis: Self Limited disease Ghons complex or Primary complex. Primary Progressive TB 10% of adults, Immunosuppressed individuals Common in malnourished children Miliary TB and Meningitis. A single lesion (the Ghon focus) occurs just under the pleura in the midportion (in the lower part of the upper lobes -- the bestventilated area) of one lung. An active Ghon focus is a 1-1.5 cm area of gray-white inflammatory consolidation circumscribed from the surrounding lung tissue. The bacilli (either free or within phagocytes) find their way to the regional (tracheobronchial) lymph nodes, and in a few weeks, granulomas have walled off the bacilli in both locations. The combination of lesions in the lung and lymph node involvement is called the Ghon complex. Healed complexes are small and may be hard to detect by either pathologic or radiologic studies. Viable bacilli remain in the Ghon focus/complex for life. Entrance into the lymphatics permits multiorgan dissemination. - The minimal lesion in the apex consists of a 1-3 cm focal area of caseous consolidation remains localized/progress slowly rapid caseation a fibrotic wall surrounds the lesion. Microscopy: Tubercule formation (by the epitheloid cells) Langhans’ giant cells Caseation (caseous necrosis) Lymphocytic infiltration Fibrosis. Course of the disease The more usual course is the fibrosis and calcification of the Ghon complex; tubercle bacilli lie dormant even with fibrosis and calcification of the granulomas. The latent phase may persist throughout life, the only index of infection being a positive PPD (purified protein derivative) reaction and the presence of the obsolete fibrocalcific Ghon complex. Subsequent course varies: occasionally because of the virulence of the organism or poor host resistance, infection spreads either via airspaces, leading to a tuberculous bronchopneumonia, or Via the bloodstream, leading to formation of myriads of small granulomas in one or several organs (miliary tuberculosis). Secondary Tuberculosis Secondary/Reactive tuberculosis Reactivation of dormant bacilli is considered the most common source of secondary tuberculosis, but reinfection from an outside source is believed to occur in some cases. The cause of reactivation is presumed to be a decline in host immunocompetence. There is increased risk for reactivation in patients with AIDS, alcoholism, diabetes, certain malignancies, or undergoing steroid or radiation therapy. Post Primary in immunized individuals Reactivation or Reinfection Apical lobes or upper part of lower lobes Caseation, cavity - soft granuloma Pulmonary or extra-pulmonary Local or systemic/miliary Secondary TB arises in a previously sensitized individual, and occurs when : bacilli escape the original Ghon focus (endogenous) or, more bacilli enter the body from outside (exogenous). The infection usually reappears in the apical or posterior segments of one or both upper lobes (Simon's foci), and progress slowly. Secondary tuberculosis active TB, postprimary tuberculosis, adult tuberculosis, reinfection tuberculosis, cavitary tuberculosis The location of granulomas is typically in the apices of the lungs. This is probably due to relatively high tissue oxygen levels in this portion of the lung. The tubercle bacillus is aerophilic. The fibrotic reaction tends to confine the typical lesion, but concurrently there is an increased tendency to tissue destruction and cavitation. Cavitation favors proliferation of organism and spread to contacts. Dissemination: Entrance into the lymphatics permits multiorgan dissemination. "Miliary" tuberculosis is characterized by numerous minute granulomas in lung and/or extrapulmonary sites. Hypersensitivity enhances resistance and induces a more prompt response by activated macrophages and fibroblasts. It is the variable spectrum of the interaction of hypersensitivity and fibrotic reaction which determines the natural course of the disease, which ranges from cure through continuous progression, or multiple exacerbations to death. -tubercle formation (by the epitheloid cells) -Langhans’ giant cells -caseation -lymphocytic infiltration -fibrosis. Other Types of Pneumonia Congenital pneumonia Pneumonitis that presents within the first 24 hours after birth. Newborn infants typically have sterile respiratory mucosa at birth, with subsequent uncontested colonization by microorganisms from the mother or environment. Accelerated access to distal respiratory structures and bypass of much of the ciliary escalator occur in infants who require endotracheal intubation. In these infants, increased physical disruption of epithelial and mucous barriers also occurs. In addition, therapeutic exposure to high oxygen concentrations and airway pressures interferes with ciliary function and mucosal integrity. Pneumonia that becomes clinically evident within 24 hours of birth may originate at 3 different times. Overlap often exists among the 3 types, and assigning a particular pneumonic episode to one of these categories may be difficult. The 3 categories of congenital pneumonia are (1) true congenital pneumonia, (2) intrapartum pneumonia, (3) postnatal pneumonia. True congenital pneumonia is already established at birth. Transmission of congenital pneumonia usually occurs via 1 of 3 routes: 1. Hematogenous transmission: If the mother has a bloodstream infection, the microorganism can readily cross the few cell layers that separate the maternal from the fetal circulation at the villous pools of the placenta. 2. Ascending transmission: Ascending infection from the birth canal and aspiration of infected or inflamed amniotic fluid have significant common features. 3. Transmission via aspiration: Most bacterial infections produce clinical signs of infection in the mother, but infections may not be evident if the membranes rupture shortly after inoculation, similar to drainage of an abscess. Intrapartum pneumonia is acquired during passage through the birth canal. Intrapartum pneumonia may be acquired via hematogenous or ascending transmission, or it may result from aspiration of infected or contaminated maternal fluids or from mechanical or ischemic disruption of a mucosal surface that has been freshly colonized with a maternal organism of appropriate invasive potential and virulence. Infants who aspirate proinflammatory foreign material, such as meconium or blood, may manifest pulmonary signs immediately after or very shortly after birth. Postnatal pneumonia in the first 24 hours of life originates after the infant has left the birth canal. Colonization of a mucoepithelial surface with an appropriate pathogen from a maternal or environmental source and subsequent disruption allows the organism to enter the bloodstream, lymphatics, or deep parenchymal structures. Enteral feedings may result in aspiration events of significant inflammatory potential. Indwelling feeding tubes may further predispose infants to gastroesophageal reflux and other aspiration events. These infants are often relatively asymptomatic at birth or manifest noninflammatory pulmonary disease consistent with gestational age, but they develop signs that progress well after 24 hours. Agents of chronic congenital infection may cause pneumonia in the first 24 hours of life; Cytomegalovirus, Treponema pallidum, Toxoplasma gondii, and others, Chlamydia organisms presumably are transmitted at birth during passage through an infected birth canal, although most infants are asymptomatic during the first 24 hours and develop pneumonia only after the first 2 weeks of life. Pathology: Macroscopy The lung may have diffuse, multifocal, or very localized involvement with visibly increased density and decreased aeration. Frankly hemorrhagic areas and petechiae on pleural and intraparenchymal surfaces are common. Airway and intraparenchymal secretions may range from thin and watery to serosanguinous to frankly purulent and frequently are accompanied by small-to-moderate pleural effusions that display variable concentrations of inflammatory cells, protein, and glucose. Microscopy Mononuclear cells (macrophages, natural killer cells, small lymphocytes) usually are noted early, Granulocytes (eosinophils, neutrophils) typically become more prominent later. If systemic neutropenia is present, the number of inflammatory cells may be reduced. Microorganisms. Alveoli may be atelectatic from surfactant destruction or dysfunction, partially expanded with proteinaceous debris (often resembling hyaline membranes), or hyperexpanded secondary to partial airway obstruction from Hemorrhage in the alveoli and in distal airways is frequent. Vascular congestion is common; vasculitis and perivascular hemorrhage are seen less frequently. Inflammatory changes in interstitial tissues are less common in newborns than in older individuals. Examination of the placenta may be useful. An unusually large placenta with a thick umbilical cord or necrotizing funisitis is suggestive of congenital syphilis, with an increased risk of congenital pneumonia alba. Bronchiolitis Obliterans Organizing Pneumonia Characterized by the presence of granulation tissue in the distal air spaces. When associated with granulation tissue in the bronchiolar lumen, organizing pneumonia is qualified by the term bronchiolitis obliterans (BO). Hence, the term bronchiolitis obliterans organizing pneumonia is used. Organizing pneumonia may be classified according to whether (1) its cause is determined, (2) its cause is undetermined but occurring in a specific and relevant context, or (3) it is Cryptogenic (idiopathic) organizing pneumonia (COP). Cryptogenic organizing pneumonia is a clinicopathologic syndrome characterized by rapid resolution with corticosteroids but frequent relapses when treatment is tapered or stopped. Pathophysiology: Approximately one half of cases of Bronchiolitis obliterans organizing pneumonia (BOOP) are idiopathic. A variety of conditions are associated with BOOP as follows: Radiation therapy: In patients treated with radiation therapy for small cell bronchogenic carcinoma or breast cancer, BOOP may affect the ipsilateral or contralateral lung. Infections: Infection may be caused by Coxiella burnetii, Pseudomonas aeruginosa,Mycoplasma species, human herpesvirus 7 (after lung transplantation), Pneumocystis carinii in patients (after liver transplantation), influenza A virus, measles virus, parvovirus B19, HIV, Chlamydia species, Plasmodium vivax, or Plasmodium malariae. Drugs and toxins: BOOP is associated with exposure to minocycline; gold; cephalosporin; acebutolol; sulfasalazine; mesalazine; bucillamine; interferon beta-1a; nitrofurantoin; amiodarone; ticlopidine; carbamazepine; phenytoin; sotalol; rapid intravenous cyclophosphamide pulse therapy; a combination of cytosine arabinoside, anthracyclines, and massive Ltryptophan ingestion, Sauropus androgynus vegetable poisoning, exposure to paint aerosols in textile workers, nylon flock workers, silo-filler's disease, free-base cocaine use, and smoke inhalation. Associated pathologies Connective tissue disease Rheumatoid arthritis, Sjögren syndrome, ankylosing spondylitis, polymyositis-dermatomyositis, cutaneous vasculitis, Behçet disease, Wegener granulomatosis, ulcerative colitis, Crohn disease, systemic sclerosis, systemic lupus erythematosus, systemic lupus erythematosus with antiphospholipid syndrome, primary biliary cirrhosis, and thyroiditis Immunosuppressed states Hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT), graft versus host disease of the liver after allogenic bone marrow transplantation, renal transplantation, coronary artery bypass graft surgery, kidney transplantation with Fabry disease, T-cell leukemia, primary non-Hodgkin lymphoma, malignancies in children, myelodysplastic syndrome, recent surgery, severe pneumonia, adult respiratory distress syndrome, and acquired immune deficiency syndrome Pneumonia in Immunocompromised patients Pneumonia in the immunocompromised host involves infection and inflammation of the lower respiratory tract. It most commonly is seen in patients infected with a human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), myelosuppressive chemotherapy, organ transplantation, traditional immunosuppressive illness Hodgkin disease. Etiology P carinii (in HIV-seropositive individuals) Gram-negative bacilli Staphylococcus and Aspergillus species (predominant in patients with cancer) Fungi Viruses (particularly CMV) P. carinii initially with bone marrow transplantation and Streptococcus pneumoniae more common later Nosocomial bacteria initially in renal transplantation, with opportunistic pathogens more common later (eg, cytomegalovirus, P. carinii; Legionella, Aspergillus, Nocardia species) Mycobacterium avium-intracellulare (AIDS) Gram-negative bacilli initially with heart or liver transplantation. Complications: Pneumothorax Hypoglycemia (may occur with pentamidine) Respiratory failure Adult respiratory distress syndrome Superinfection Pleural effusion Empyema Death. ...in Immunocompromised patientsAspergillus and fungus ball Aspergillosis Chemical Pneumonies Many substances can cause chemical pneumonia, including liquids, gases, and small particles, such as dust or fumes, also called particulate matter. Some chemicals only harm the lungs; however, some toxic materials affect other organs in addition to the lungs and can result in serious organ damage or death. Chemical pneumonia includes: Insecticides Pool cleaning chemicals Gasoline fumes Toxic gas (phosgene, chlorine) Aspirated/Inhalated chemicals Complications of Chemical inhalation: Cyanosis Pneumonia Respiratory failure. Aspiration Pneumonia Aspiration (the act of taking foreign material into the lungs), can cause a number of syndromes determined by the quantity and nature of the aspirated material, the frequency of aspiration, and the host factors that predispose the patient to aspiration and modify the response. Three types of material cause 3 different pneumonic syndromes. Aspiration of gastric acid causes chemical pneumonia (Mendelson syndrome). Aspiration of bacteria from oral and pharyngeal areas causes bacterial pneumonia. Inhalation/aspiration of chemicals Aspiration of oil, eg, mineral oil or vegetable oil, causes exogenous lipoid pneumonia, a rare form of pneumonia. Organic dusts (hypersensitivity pneumonitis) Inorganic particulates (silica, asbestos, talc, zinc) Chemical fumes (sulfuric acid, hydrochloric acid, methyl isocyanate) Gases (oxygen, chlorine, nitrogen dioxide [silo-filler disease], ammonia, CO). Mendelson syndrome The parenchymal inflammatory reaction caused by a large volume of gastric contents independent of infection. If the pH of the aspirated fluid is less than 2.5, it has a greater potential for causing chemical pneumonia. The initial chemical burn is followed by an inflammatory cellular reaction fueled by the release of potent cytokines (tumor necrosis factor–a Bacterial pneumonia Nosocomial. The major pathogens involved are hospitalacquired flora through oropharyngeal colonization (eg, enteric gram-negative bacteria, staphylococci). In anaerobic pneumonia, the pathogenesis is related to the large volume of aspirated anaerobes (eg, as in persons with periodontal disease) and to host factors (eg, as in alcoholism) that suppress cough, mucociliary clearance, and phagocytic efficiency. Colonization of gram-negative organisms in the oropharynx, sedation, and intubation of the patient's airways are important pathogenetic factors in nosocomial pneumonia. Risk factors Conditions associated with altered or reduced consciousness Alcoholism Drug overdose Seizures Stroke Head trauma General anesthesia Dysphagia Esophageal strictures Esophageal neoplasm Esophageal diverticula Tracheoesophageal fistula Gastroesophageal reflux disease Multiple sclerosis Dementia Parkinson disease Myasthenia gravis Pseudobulbar palsy Mechanical conditions Esophageal conditions Neurologic disorders Nasogastric tube Endotracheal intubation Tracheostomy Upper gastrointestinal endoscopy Bronchoscopy Other types of conditions Protracted vomiting General deconditioning and debility Prolonged recumbency Amniotic material Eosinophilic pneumonia Characterized by pulmonary eosinophilia and infiltrates, with or without increased peripheral eosinophils in the blood. Causes: Primary Eosinophilic pneumonias are idiopathic and are not related to drugs, medications, or systemic diseases such as vasculitis. Secondary Eosinophilic pneumonias are induced by Parasites (eg, Ascaris lumbricoides, Strongyloides stercoralis), Medications (eg, amiodarone, nitrofurantoin). Histologic Findings Eosinophils with edema in alveolar spaces and bronchioles are observed. Additional cells are nonspecific and can include monocytes, histiocytes, and polymorphonuclear leukocytes or neutrophils (PMN). 2. Lung Abscess Lung Abscess Focal suppuration with necrosis of lung tissue Strep, Staph & Gram negative & anaerobes Mechanism: Aspiration of infected material Post pneumonic Septic embolism Neoplasms Direct trauma Spread from adjacent structures. Abscesses may occur in any location in the lung; they may be single or multiple. Abscesses due to aspiration occur most commonly in the right lung (because of the more vertical course of the right main stem bronchus) and are usually single. Morphologically an abscess is a cavity filled with suppurative debris. If communication exists with an airway, the exudate may drain, leading to air in the cavity, and an air-fluid level on chest x-ray. In chronic abscesses, there may be peripheral fibroblastic proliferation resulting in a fibrous wall. Complications: Empyema Systemic spread (pyemia/pyemic abscesses) Septicemia. Lung Abscess Lung Abscess Chronic Lung Abscess Fungal Abscess: Candida albicans Thank you for your interest