* Your assessment is very important for improving the work of artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download File - Ancient Greece Persia

History of science in classical antiquity wikipedia , lookup

Regions of ancient Greece wikipedia , lookup

Pontus (region) wikipedia , lookup

Greek contributions to Islamic world wikipedia , lookup

Pontic Greeks wikipedia , lookup

List of oracular statements from Delphi wikipedia , lookup

Ancient Greek literature wikipedia , lookup

Ancient Greek religion wikipedia , lookup

Ionian Revolt wikipedia , lookup

Second Persian invasion of Greece wikipedia , lookup

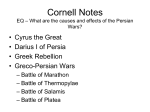

ANCIENT GREECE AND PERSIA THE WORLD'S FIRST CLASH OF CIVILIZATIONS GREEK PERSIAN WARS BATTLE OF SALAMIS MONUMENT THE GREATEST AND MOST DECISIVE BATTLES IN WORLD HISTORY The Greek Persian Wars started with the Battle of Marathon in 490 BC, which was the Persian Empire’s first assault wave against the West. The second assault wave came with a series of battles in 480-479 BC, including the Battle of Thermopylae that gained popular attention a few years ago with a 2007 movie focused on the last stand of 300 Spartans against the Persians in the mountain pass at Thermopylae. Reading below, you will quickly learn that lists of the greatest and most decisive battles in all of human history often include three battles of the Greek Persian Wars. Before turning our attention to battles of the Greek Persian Wars, we should take a moment to consider assertions that this or that battle was "the greatest and most decisive." Such contentions can result in a never-ending parlor game that fails to resolve differing opinions because the game is largely based on "what-if" questions. What if the outcome of a battle had been different? What if the victors had been defeated? What then? This parlor game is speculative and subject to ongoing debate so reasonable people can make persuasive Copyright © 2016 Ancient Greece and Persia: The World's First Clash of Civilizations. All Rights Reserved. arguments for differing views. Nevertheless, the game can be worthwhile because it sharpens the mind about the significance of historical events that relate to us today, as individuals and as a society. The point is simple – what happened to our predecessors and ancestors is a key ingredient in the mix that makes us what we are and binds us to one another. We are well advised to at least occasionally reflect on times long ago because understanding those past times is a necessary part of following the ancient Greek maxim – Know Thyself. Before departing for ancient and often confusing times, let’s consider the "what-if" question in a more recent and familiar context: What was the greatest and most decisive battle fought during World War II? A little internet research will suggest one likely answer is The Battle of Britain. What if Winston Churchill’s "blood, sweat and tears" had not been sufficient for the British to keep a stiff upper lip and The Battle of Britain ended in victory for Germany? Then, with all Europe under Hitler’s thumb, what if The Fuehrer did not need to divide his war-making forces and Germany was not fighting on two fronts after it attacked the Soviet Union? Then, with Europe and the Soviet Union subjugated, what if Hitler gazed with squinted eyes west across the Pacific Ocean to an isolated America, while Japan glared east across the Atlantic. Then what? Food for thought about happenings not so long ago. Now let’s go back in time about 2,500 years. We will begin by getting the lay of the land. THE LAY OF THE ANCIENT LAND Use the map below to follow along on the tour. The map shows numerous important place names. To help get our bearings, let’s describe the map starting at the bottom-center. Copyright © 2016 Ancient Greece and Persia: The World's First Clash of Civilizations. All Rights Reserved. LAND OF THE ANCIENT GREEKS AND WESTERN PERSIA The island at the bottom-center of the map is Crete in the Mediterranean Sea. South of Crete (beyond the map’s boundary) is the continent of Africa with Libya and Egypt as the two closest African countries to Crete. Moving up, northwest of Crete, you will see the city of Sparta in southern Greece. The area of southern Greece (up to the city of Corinth) is called the Peloponnese. The body of water to the far left (west) of Greece is the Ionian Sea, and further west (beyond the map’s boundary) is Italy. The body of water to the right (east) of Greece is the Aegean Sea. The Aegean Sea separates Greece from modern-day Turkey to the far right, and both the Ionian and Aegean Seas are part of the Mediterranean Sea. Moving north from Sparta to cross the Isthmus at Corinth and leave the area of the Peloponnese, you come to the city of Plataea. Although small, Plataea played outsized roles at the beginning and end of the Greek Persian Wars. The Wars started in 490 BC with the Battle of Marathon, and the Greek soldiers (called hoplites) who fought at Marathon consisted of 9,000 Athenians and 1,000 Plataeans. Eleven years later, in 479 BC, the final land battle against the Copyright © 2016 Ancient Greece and Persia: The World's First Clash of Civilizations. All Rights Reserved. Persians was fought near Plataea by an alliance of Greek city-states. For a moment, glance to the far right (east) across the Aegean Sea to modern-day Turkey (also known as Anatolia or Asia Minor), which was just a small part of the vast Persian Empire. Note the island of Samos just off the coast and, near the coast to the northwest of Samos, the city of Ephesus (famous in the ancient Greek, Roman and Christian eras). On the coast between Samos and Ephesus is Mount Mycale (not shown on the map). In 479 BC, the sea and land Battle of Mycale was fought about the same time as the Battle of Plataea. With the Greeks victorious in both battles, the Greek Persian Wars came to an end. Now back to Plataea on the Greek mainland. Moving south from Plataea you will pass a small, unnamed island just off the coast and, beyond that, you will see the island of Aegina. As with many of this map’s place names, Aegina will appear and reappear later in our narrative as historical events unfold. For example: Aegina is the likely place where the first coins of Europe were made; Aegina was a major economic (and sometimes military) competitor to Athens; Aegina’s rivalry with Athens was used by the cunning leader of Athens, Themistocles, to trick his fellow Athenians so they unwittingly prepared for a battle against the Persians that the Athenians did not see coming. But those stories will come later. Now go back up north from Aegina to that small, unnamed island between Aegina and Plataea. There is a fitting coincidence in the fact this island is unnamed on the map. If you were to ask a random person on the street to name a battle fought during the Greek Persian Wars, you would usually find yourself stared at as if you had three heads. But on rare occasions you would get a response, and the most likely answers would be either Marathon or Thermopylae. Fair enough, but those two battles were not decisive because the Persians came back again ten years after Marathon and the Greeks lost at Thermopylae. So what if you then asked, “What about the Battle of Salamis?” Once again, the odds are good you would be looked at as if you had three heads. That small unnamed island just off the coast to the south of Plataea and west of Athens is Salamis for which the 480 BC Battle of Salamis is named – and the Battle of Salamis was decisive. Granted, there were two more major battles after the Battle of Salamis, but Salamis is what really broke the Persians and their Great King, Xerxes, who fled the land of the Greeks after this battle. As will be discussed later, the Battle of Salamis is arguably the most significant battle of the Greek Persian Wars, and the Battle of Salamis has a strong claim to be acknowledged as the greatest and most decisive battle ever fought in all of world history. We also will see later that one man – and one man alone – had the amazing foresight, political cunning, tactical savvy and strategic genius to lead the Greeks to a victory that saved Western Civilization from subjugation by the Persian Empire. That man was Themistocles whose accomplishments we will consider when we learn later why he was the hero of another man with a very impressive military and political background – five-star general and U.S. President, Dwight D. Eisenhower. Back to the map: From the unnamed island of Salamis move east to Athens and, from there, go northeast to Marathon. Marathon is 26 miles from Athens, and the Battle of Marathon is Copyright © 2016 Ancient Greece and Persia: The World's First Clash of Civilizations. All Rights Reserved. where the Greek Persian Wars started in 490 BC. Shortly, we will discuss this profound event in some detail as well as the “Mysteries of Marathon.” But first, let’s finish the map. From Marathon, go northwest to Thermopylae, which is a mountain pass in northern Greece where the Battle of Thermopylae was fought in 480 BC. The dramatic last stand of King Leonidas and his 300 fellow Spartans, along with contingents of hoplites from other Greek citystates, made this struggle so memorable. To the east of Thermopylae you will see the northern edge of a large and long Greek island that stretches down the east coast of Greece beyond Marathon. This is the island of Euboea (not identified on the map but its major city of Eretria is identified). The northern point or head of Euboea was known as Artemisium in ancient times. It was in these waters off northern Euboea that the Battle of Artemisium took place while the Battle of Thermopylae was underway. So the Greeks fought two major battles simultaneously, on land and sea, in a futile effort to stop the advancing Persians. Now move far north to the area of Macedonia, which had a complex relationship with the Greeks to the south – a relationship that varied over time. In some ways Macedonia was “Greek” but in other ways it was not. During the time of the Greek Persian Wars, Macedonia was a Greek kingdom but beyond the influence sphere of the three major Greek city-states – Athens, Sparta and Thebes (Thebes is located on the map about halfway between Athens and Thermopylae). And for a period, Macedonia was even subjugated by Persia, so this is where the Persian Empire extended its tentacles the greatest distance into Western Civilization. But this is not what Macedonia is primarily remembered for. That came more than a century later with the rise of Macedonian King Philip II who, with his phalanxes of long spears, dominated all the other Greeks and then his son, Alexander the Great, used those same long-speared phalanxes to dominate the entire known world. But that is another story. From Macedonia on the map, move far to the east and you arrive in the land of Thrace. You are still in modern-day Europe, today’s Bulgaria. But during 490–479 BC, Thrace became part of the Persian Empire. Moving farther east you come to the city of Byzantium, later renamed Constantinople after the Roman Emperor Constantine I, or Constantine the Great (272–337 AD), who established Christianity as the official religion of the Roman Empire. Later, Constantinople was renamed again as Istanbul when the city was conquered by the Ottoman Empire in 1453 AD. Today, Istanbul is the most populous city in Turkey and serves as the “bridge” between the East and West. In fact, today there are two real bridges in Istanbul that connect “Asia” with “Europe” by crossing a narrow straight of water called the Bosporus. The Bosporus, in turn, connects the Sea of Marmara to the south with the Black Sea to the north (upper right corner of the map). (Note that the Bosporus, Sea of Marmara and Black Sea are not identified by name on the map.) During the time of the Greek Persian Wars, there was another “bridge” between the East and West. On the map move down to the city of Troy. This is the city made famous by the Trojan War (approx. 1200 BC) and Homer’s Iliad and Odyssey (approx. 750 BC). Just north of Troy and east of the island of Imbros, there is a long, narrow straight of water that connects the Aegean Copyright © 2016 Ancient Greece and Persia: The World's First Clash of Civilizations. All Rights Reserved. Sea with the Sea of Marmara. This narrow strip of water, separating East and West, was known as the Hellespont in ancient times (today it is called the Dardanelles). The Hellespont is where Xerxes, the fourth Great King of the Persian Empire, had his engineers lash together over 300 ships to build a gigantic pontoon bridge so the massive Persian army could cross from East to West and descend on the Greeks in 480 BC. (Actually, Xerxes needed to build two pontoon bridges because the first one was destroyed by a storm’s roiling waters. In response, Xerxes had the waters whipped 300 times and branded with hot irons while the Persian soldiers screamed at the disrespectful waters. Duly admonished and punished, the waters submitted to the Great King, and the huge Persian army safely crossed the Hellespont on the second pontoon bridge.) When Xerxes led his Persian hordes across the Hellespont on the second pontoon bridge, they arrived on a long peninsula in southern Thrace. In ancient times this peninsula was known as Thracian Chersonese. Today the peninsula is known as Gallipoli. (Twelve years before Xerxes crossed the Hellespont, Thracian Chersonese had been ruled by an enigmatic Greek leader – Miltiades – who played a major role in the Battle of Marathon that we will consider shortly.) From the Hellespont on the map, go southeast to the city of Sardes (often spelled Sardis) located in the land called Lydia. Previously, we mentioned that the island of Aegina probably was the location where the first coins in Europe were made. The Aeginetes got the idea for coins from the land of Lydia where the first coins in the world were made. About a century after the development of coinage, Lydian King Croesus (approx. 595–546 BC) came to power, and the city of Sardes was his capital. Croesus was the richest man in the world at the time, but his wealth did not protect Croesus from threats brewing in the east as the nascent Persian Empire was expanding in all directions under the rule of the empire’s founder and first Great King, Cyrus. Croesus was uncertain what to do about Cyrus so Croesus sent emissaries to Delphi to get advice (on the map you will find Delphi west of Plataea on the north shore of the Corinthian Gulf). Delphi was the home of the most famous oracle in the world. (Today, we tend to think of an “oracle” as a message or prediction that often is ambiguous and easily misinterpreted. But the word “oracle’ also can refer to the person who delivers the vague prediction, and the Oracle of Delphi was a priestess known as the Pythia.) The Pythia told King Croesus’ emissaries that if Croesus attacked Cyrus, Croesus would destroy a great empire. So Croesus attacked and, as predicted, Croesus destroyed a great empire – his own. Thus, Cyrus the Great extended the Persian Empire west to edge of the Aegean Sea. Sardes was one of the most important cities in the western portion of the vast Persian Empire. Sardes also was the western endpoint of the Persian Royal Road that extended east from Sardes for more than 1,500 miles (over 2,400 km) to the city of Susa. (To find Susa on a full map of the Persian Empire, go to the “Persian Culture” tab on this site and click on that map to enlarge it. Susa is located in the central, southern portion of the Persian Empire, east of Babylon and north of today’s Persian Gulf.) The full length of the Persian Royal Road could be traversed within a mere seven days – an amazing speed accomplished by relay riders on horseback who carried messages to and from the Great King. (Think about America’s pony express.) According to Herodotus (484–425 BC), the “Father of History” who is our primary source for what happened during the Greek Persian Wars, the Persian relay riders of the Royal Road adhered to a creed that much later became the unofficial creed of the United States Copyright © 2016 Ancient Greece and Persia: The World's First Clash of Civilizations. All Rights Reserved. Postal Service as inscribed on the James Farley Post Office in New Your City: “Neither snow nor rain nor heat nor gloom of night stays these couriers from the swift completion of their appointed rounds.” On the map move down to the city of Halicarnassus, the last destination on our tour. Halicarnassus was founded as a Greek colony – one of many Greek colonies on the coast of Anatolia to the east of Greece across the Aegean Sea as well as to the west across the Ionian Sea on the coast of Italy. Halicarnassus is perhaps best known as the site of one of the Seven Wonders of the Ancient World – the tomb of Mausolus who ruled the land of Caria (see map) from 377 to 353 BC. The word “mausoleum” is derived from Mausolus, so his tomb and World Wonder also is known as the Mausoleum at Halicarnassus. A century before Mausolus, another important ruler of the land of Caria resided in Halicarnassus – Queen Artemisia I. Her primary claim to fame was as a valiant fighter and ship commander during the Battle of Salamis (480 BC). Although she was from a Greek colony, Queen Artemisia I fought for Xerxes because all the Greek colonies in Anatolia were subjugated by the Persian Empire at that time. Finally, most of what we know about Queen Artemisia I – and, for that matter, most of what we know about everything related to the Greek Persian Wars – comes from the most famous person born in Halicarnassus – Herodotus (484–425 BC). Herodotus was the world’s first true historian, so he is known as the “Father of History.” His claim to fame is his masterpiece – The Histories – devoted to the Greek Persian Wars. Humbly following in Herodotus’ profound footsteps, we now turn our attention to a quick overview of the major battles of the Greek Persian Wars. The previous tour of the lay of the ancient land roughly followed the geography of the map. The following overview will summarize the major battles of the Greek Persian Wars in chronological order. In addition, there will be a few comments on the images associated with the battles. BATTLE OF MARATHON The Battle of Marathon, fought in 490 BC, was the Persian Empire’s first assault wave to wash away the cradle of Western Civilization. The odds against the Greeks were staggering. The Greeks were heavily outnumbered, although it is uncertain exactly by how many. A reasonable estimate is that about 40,000 Persian soldiers fought 10,000 Greeks (9,000 Athenians plus 1,000 Plataeans). In addition, there may have been another 40,000 Persian sailors, although most of them probably did not directly engage in the battle. The Persian advantages consisted of more than numbers – much more. The Persian archers were deadly at both long and short range. As the Greek and Persian formations marched toward each other, Persian archers would begin by aiming high to rain arrows at maximum distance, and as the enemy formations closed the archers would progressively lower their aim to finally shoot parallel to the ground and point blank into the midst of the oncoming Greeks. The Persians had hundreds of bowmen and the Greeks had few if any. Even more important, the Persians had their warhorses. The Persian cavalry numbered perhaps a thousand horses and riders using bows and arrows while the Greeks had none. The Persian Copyright © 2016 Ancient Greece and Persia: The World's First Clash of Civilizations. All Rights Reserved. horses could race up and down the sides or flanks of the enemy, out of the Greeks’ spearthrowing range but well within the range of the arrows whistling in from the deadly accurate bowmen atop their galloping steeds. Their cavalry was one the Persians’ greatest advantages, and that fact leads to perhaps the most intriguing of all the “Mysteries of Marathon.” After we summarize the various battles of the Greek Persian Wars, we will turn to those fascinating “Mysteries of Marathon,” beginning with the question: What happened to the Persian cavalry at Marathon? Now for a few brief comments about this website’s images associated with the Battle of Marathon. AESCHYLUS The most famous person to fight at Marathon was Aeschylus, and what he thought about his participation in the battle reveals a lot about the mentality of ancient Greeks. Today, we know Aeschylus because of his writings. He is the “Father of Tragedy” – the first of the renowned trio of ancient Greek tragedians, along with Sophocles and Euripides. Aeschylus’ surviving plays include: The Persians (based on the Battle of Salamis in which Aeschylus also fought ten years after Marathon); Seven Against Thebes; The Suppliants; The Oresteia; Prometheus Bound. A strong argument can be made that Aeschylus has only one rival who might be a worthy contender for the title of “best” playwright ever – Shakespeare. Given his profound literary reputation, one might expect Aeschylus to mention his accomplishments in the epitaph on his tomb that he most likely wrote about himself before he died in the land of Gela, in Sicily. Indeed, that epitaph does identify the lifetime accomplishment that was most important to Aeschylus and, as previously noted, his thinking provides insight into the minds of ancient Greeks: Beneath this stone lies Aeschylus, the Athenian, son of Euphorion, who died in Gela’s wheat-growing land. His glorious valor the hallowed Plain of Marathon can tell, Copyright © 2016 Ancient Greece and Persia: The World's First Clash of Civilizations. All Rights Reserved. and the long-haired Persians know it well. The Greeks revered valor and glory. “Valor” is akin to “courage.” Valor is internal; it resides within a person and is manifested by action. That action, for an ancient Greek man, often meant “stand your ground” and “fight to the death.” For an ancient Greek woman, valor often meant to “endure,” to “persevere” – to remain “steadfast” and “true.” For those familiar with Homer’s Odyssey, think of Penelope’s faithful 20-year wait for the return of her husband. “Glory” was different. Glory was external to the being of an ancient Greek. Glory was determined by others and what they thought about an individual, especially an individual’s valor. Glory meant recognition and respect. Ultimately, glory meant that an ancient Greek was worthy of the highest goal – to be remembered long after the person’s soul departed for the Underworld (Hades). The Battle of Marathon ranks extremely high in terms of both valor and glory. It naturally follows that the name of the man who led the Greeks in this first clash of civilizations would have been celebrated and his name passed down to following generations to be remembered in perpetuity. However, the leader of the Greeks at Marathon is uncertain. One of two possibilities is Miltiades, a complex character with a dubious reputation. The profile image of Miltiades’ smashed, bronze helmet is from the Archaeological Museum of Ancient Olympia. (Scroll down for a different perspective of a portrait image of an intact bronze Corinthian helmet [named after the city-state of Corinth].) Miltiades offered his helmet to the Temple of Zeus at Olympia, and the inscription on the helmet states, “Miltiades dedicates this helmet to Zeus.” It is cause for reflection that, 2,500 years after the fact, we can look upon a real helmet that was used in the real Battle of Marathon (although some scholars, who often seem to enjoy spoiling our otherwise uplifting imagination, suggest that Miltiades’ helmet may have been dedicated before the battle instead of being used in the battle). MILTIADES' HELMET MILTIADES’ HELMET Miltiades (550–489 BC) was born into a prominent Athenian family. In his mid-30s, Miltiades left his homeland to become the ruler of the Thracian Chersonese (today’s Gallipoli). Miltiades went to the Chersonese to replace his brother who had been the ruler until an ax cleaved his head. Upon his arrival, Miltiades went into mourning for his brother and invited all the local leaders to offer their condolences. They dutifully obliged and all of them ended up imprisoned Copyright © 2016 Ancient Greece and Persia: The World's First Clash of Civilizations. All Rights Reserved. by Miltiades who then hired 500 hundred mercenaries to ensure loyalty throughout the land. Miltiades also married the daughter of the King of Thrace (located immediately north of the Chersonese) in order to form an alliance and strengthen Miltiades’ rule. Miltiades maneuvers and manipulations worked well for a few years, but then an overwhelming threat emerged in the east. The Persian Empire, under the rule of Great King Darius (550–486 BC), was expanding toward the Chersonese and all of Thrace. Miltiades responded by demonstrating his well-deserved instinct for survival that relied on shrewd duplicity. He joined forces with Darius. Then for years Miltiades fought with the Persians, and his subservience lasted until Miltiades thought he could outfox Darius by abandoning the Great King in a battle campaign that should have ended with Darius’ death. But Great Kings are neither easily outfoxed nor easily killed. Darius survived so the tables turned and Miltiades had to run for his life. He ran straight back to Athens in 492 BC, two years before the battle of Marathon. There are several reasons to believe that Miltiades was the leader of the Athenians at Marathon, including the following three: First, when Miltiades returned to Athens he brought something with him that no other Athenian possessed – an up close and personal knowledge of exactly how the Persians thought and fought, their tactics and strategy. Second, subsequent to Miltiades’ death about a year after the Battle of Marathon, he was widely acknowledged as the Greek leader during the battle. The third and by far most persuasive reason to believe that Miltiades led the Greeks at Marathon is that the Father of History, Herodotus (484–425 BC), recognized Miltiades as the leader. (For an image and discussion of Herodotus, go to this website’s Resources/Contact Us page.) Herodotus’ The Histories, written a generation after Marathon, is without question the most authoritative source about the Greek Persians Wars in general and the Battle of Marathon in particular. While it is well established that Herodotus sometimes exaggerated and embellished his historical accounts, we must be very cautious to declare Herodotus wrong. Thus, the majority of scholars accept that Miltiades was, indeed, the Greek leader at the Battle of Marathon. However, there are potent arguments that Herodotus was, in fact, wrong. To be continued…. MARATHON TOMB OF 192 ATHENIANS MARATHON BEACH TODAY A decade later, in 480-79 BC, Persia’s second wave hit the West with a series of struggles on Copyright © 2016 Ancient Greece and Persia: The World's First Clash of Civilizations. All Rights Reserved. land and sea: BATTLE OF ARTEMISIUM A sea battle off the coast of Greece while a land battle was underway at Thermopylae. BATTLE OF THERMOPYLAE Leonidas, King of Sparta, made a famous last stand at the mountain pass in northern Greece. The dramatic battle was memorialized in a movie focused on the last 300 Spartans who fought and died in the shade because the Persian arrows were so many they blotted out the sun. LEONIDAS THERMOPYLAE ARROWHEADS THERMOPYLAE TODAY BATTLE OF SALAMIS After the Persians burned Athens to the ground, the Athenian leader, Admiral Themistocles, made his stand with his "wooden wall" of warships called triremes. The Persians had so many more fighters and ships that the Greeks had absolutely no chance. But there was one wildcard. Themistocles was the most cunning man in the entire world. THEMISTOCLES BATTLE OF SALAMIS BATTLE OF PLATAEA The final land battle of the Greek Persian Wars when the Spartan soldiers, called hoplites, slowly marched forward – the Spartans always moved with very slow and steadfast conviction – Copyright © 2016 Ancient Greece and Persia: The World's First Clash of Civilizations. All Rights Reserved. and proved that the Greek phalanx was an irresistible force against Persian hordes that were not an immovable object. BATTLE OF MYCALE This land and sea battle, in conjunction with the land Battle of Plataea, ended the Greek Persian Wars. CORITHIAN HELMET We are dealing with six battles that are mysterious in many ways, partly because most people know next to nothing about these clashes and partly because even expert historians who specialize in this era often do not understand exactly what happened. The final outcomes of the battles may be well known, but what occurred during the battles and, most importantly, how the ultimately victorious Greeks accomplished their feats, remain mysteries. Time to narrow our focus and start at the beginning: The Battle of Marathon is a prime candidate for being among the greatest and most decisive battles in world history. Also, this first battle of the Greek Persian Wars is an excellent example of facts shrouded in mystery. We will start with a summary of facts and then examine the "Mysteries of Marathon." To be continued.... PHALANX Copyright © 2016 Ancient Greece and Persia: The World's First Clash of Civilizations. All Rights Reserved. Copyright © 2016 Ancient Greece and Persia: The World's First Clash of Civilizations. All Rights Reserved.