* Your assessment is very important for improving the workof artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

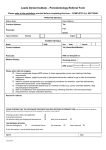

Download Prevention and treatment of periodontal diseases in

Maternal health wikipedia , lookup

Race and health wikipedia , lookup

Medical ethics wikipedia , lookup

Hygiene hypothesis wikipedia , lookup

Focal infection theory wikipedia , lookup

Patient safety wikipedia , lookup

Adherence (medicine) wikipedia , lookup

Management of multiple sclerosis wikipedia , lookup