* Your assessment is very important for improving the workof artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download 285 pdf - Hans L Zetterberg`s Archive

Universal grammar wikipedia , lookup

Philosophy of history wikipedia , lookup

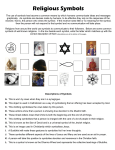

Symbol grounding problem wikipedia , lookup

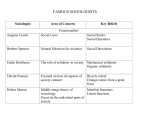

Sociological theory wikipedia , lookup

The Dispossessed wikipedia , lookup

Social theory wikipedia , lookup

State (polity) wikipedia , lookup

History of linguistics wikipedia , lookup

Tribe (Internet) wikipedia , lookup

Sociology of knowledge wikipedia , lookup

Social development theory wikipedia , lookup

Neohumanism wikipedia , lookup

Differentiation (sociology) wikipedia , lookup

Unilineal evolution wikipedia , lookup

Societal collapse wikipedia , lookup

Other (philosophy) wikipedia , lookup

Symbolic interactionism wikipedia , lookup

Symbolic behavior wikipedia , lookup