* Your assessment is very important for improving the workof artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download File - Fortismere A level Art history

Women in the Middle Ages wikipedia , lookup

Early Middle Ages wikipedia , lookup

Medieval music wikipedia , lookup

Islamic world contributions to Medieval Europe wikipedia , lookup

Medieval Inquisition wikipedia , lookup

England in the Middle Ages wikipedia , lookup

Estates of the realm wikipedia , lookup

Wales in the Early Middle Ages wikipedia , lookup

Dark Ages (historiography) wikipedia , lookup

European science in the Middle Ages wikipedia , lookup

Feudalism in the Holy Roman Empire wikipedia , lookup

Medieval technology wikipedia , lookup

Medievalism wikipedia , lookup

Late Middle Ages wikipedia , lookup

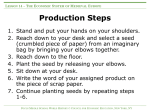

Historical background to Medieval Europe: For the first ten minutes of this lesson, go through the images on your handout nd try to learn as much about medieval Europe and medieval art (style, composition, medium etc) as you can. The more you look, the more you will be able to guess at, so take your time and do not give up when you have got a simple answer. Feedback: Now you have looked for yourselves, try to match up the portions of historical background to the relevant image. Think carefully about this, and don’t stick anything down until we have gone over the answers… The final collapse of Rome’s Roman power – the last western emperor abdicated in 476 – occurred shortly after a Bishop of Rome, Leo I, was stressing his role as direct heir to Peter. But for a century Rome declined, passing between warring parties including Lombards and Byzantines (Eastern Romans). The population shrank to perhaps 30,000 and the senate, a relic from the republic, vanished in 580. Giotto, Confirmation of the Rule, 1299, fresco Then arose the medieval papacy, a reshaping of western Christianity around the Pope in Rome, initiated by Gregory the Great in the sixth century. As Christian rulers emerged from across Europe, so the power of the Pope and the importance of Rome grew, especially for pilgrimages. As the wealth of the Popes grew, Rome became centre of a grouping of estates, cities and lands known as the Papal States. Rebuilding was funded by the Popes, Cardinals and other wealthy church officials. The Magyars' arrival in the Carpathian Basin depicted in the Illuminated Chronicle c. 1360 Charlemagne’s death in 814 brought about the beginning of a very turbulent period in European history. His empire had begun to crumble a decade earlier and then began to disintegrate into anarchy within the three nominal areas ruled by his descendants – roughly corresponding with present-day Germany, France and a central strip running from the Netherlands to Switzerland. It also came under constant attack from outside. Muslims from Spain marauded southern and central France in search of loot and slaves. Vikings harried the northern and western coastlands, and siled up the rivers to the interior – Cologne, Rouen, Nantes, Orleans, and Bordeaux had all fallen to them before 888 ad. Then a new menace appeared: Magyars from central Asia swept into Europe, penetrating as far as Pavia in Italy in 899 and southern France by 917. Not until 924 were they forced to withdraw to Hungary and lead a more settled life. In 911 the king of the western Franks granted territorial rights to a Viking band who had settled in what was later called Normandy, their leader being titled a duke and baptised a Christian the next year. The Normans were to play a very important part in medieval Europe, especially in the long struggle between popes and Holy Roman Emperors. By 1053 a group of Norman adventurers had moved into southern Italy, where they took possession of the last Byzantine colony in the West and and went on to oust the Muslims from Sicily, while Duke William effected the conquest of England in 1066. A segment of the Bayeux Tapestry depicting Odo, Bishop of Bayeux rallying Duke William's troops during the Battle of Hastings in 1066 Ground plan of Croxden Abbey, 1176. New social structures were built up from the complex relationships binding vassal to lord, in chains which extended from peasant to king – what is now called ‘the feudal system’, though there were several kinds of feudalism and none was systematic. Similarly, monasticism developed organically, gradually acquiring the importance of a supra-national force. But not until the 12th century did the arts start to revive. The Medieval society was complex, and was not so far away from what we would call a modern one. It was governed by laws, it had rules, the people had rights and obligations. There was a legal framework of land tenure, taxation and fiscal immunities. There was an urban organization and a rural one. The Feudal system had laws regarding the relationship between lords and peasants, and between the lords and the monarch. Any society requires some sort of armed force and the Middle Ages one is no different. Military organization was remarkable, based on the corps of hereditary aristocracy and their households, but also including bodies of professional soldiers, and the national levies. Henry VIII and the Order of the Garter, 1534, illuminated manuscript. Master of the Registrum Gregorii, Registrum Gregorii, 985-1000 A.D. Manuscript, Stadtbibliothek, Trier The Church played a huge role in the Middle Ages. By fulfilling social and religious needs and allying with those in power, it secured influence and wealth. It had extensive possessions; received as pious gifts, reclaimed by monks from the wilderness, or simply bought. People living on the Church lands were subject to its authority. Thus, besides teaching people religion, the Church was also a governing body, exercising its jurisdiction by controlling and punishing the unruly. It was the main educational agency in the society of the early Middle Ages, but also was capable of ruling with the same power and duties as a monarch. All these territories had to be organized. In order to enforce justice and protect the lands from invaders armies were needed. The abbots and bishops who were the rulers of these estates were therefore the source of all local authority. They maintained order, held the courts, and raised the army. They were judges and officials of the king and had power to condemn criminals to death. They directed the schools, collected the feudal dues, and made war and peace. The elements which shaped European feudalism were the practice of commendation, the holding of fiefs, and the grants of immunity. Commendation was the act by which a free man accepted to be a vassal, commending himself to a more powerful member of the society, like a noble, a bishop, or an abbot. The vassal promised to serve his lord faithfully, in war or with advice and did not lose his position as a free man, or sink on the social scale. The lord was bound by his own obligations to support and protect his vassals and did his best to have as many as possible, as a large number of followers added importance and strength. In the later Middle Ages the old feudal order of the society was changed by the emancipation of serfs. As the serfs frequently left their land, the landlords reduced the burdens imposed upon their tenants, and tried to attract new ones. The lords who needed large sums of money for a crusade or a local war sold to their serfs the exemption from certain obligations. This custom spread, because to a certain extent landowners had to compete for labourers. Emancipation was also looked upon as a pious act, and many lords decided to free high numbers of serfs. In most of France, the worst burdens of serfdom disappeared by the beginning of the thirteenth century, and in many parts there were no serfs at all. The life of the peasants was still hard, but eventually they all became freemen. Serfs who became members of the clergy were freed at the same time, and many rose to high positions, even to the Papal throne. Medieval illustration of serfs harvesting wheat with reaping-hooks, on a calendar page for August. Queen Mary's Psalter c, 1310 Cosimo Tura, Fresco from the Palazzo Schifanoia, c. 1476 With the towns and merchant class gaining importance in the medieval society, the old order of feudalism began to change. The merchants and generally the burghers became so wealthy that the kings decided to have them as allies in their power struggle against the nobles. Throughout the Middle Ages the upper classes were themselves engaged in trade. The manorial lord sold the produce of his estates and at fairs and markets purchased everything he needed for himself and his family. In the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries, noblemen and bishops, abbots and kings themselves had ships which were doing trade with foreign countries for their profit. A considerable number of the traders of the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries were cadets of good families, as in a knight’s family, only the eldest succeeded to the family estate and honours, the rest had to provide for themselves. What strengthened the position of traders in the medieval society was their organization into powerful and wealthy guilds, which also consolidated even more the political position of the towns. Locksmith, 1451 The towns became emancipated through their growth, which was wholly due to commerce and manufacturing. From the twelfth to the fourteenth century conditions in towns improved. It was sort of win-win situation, as the lords greatly contributed to the development of commerce. They found it to their advantage to make better roads, to build bridges, and to police the routes, since for these services they demanded heavy taxes from the merchants. Later the charges consisted of a fixed amount, and were no longer dictated by the lord’s pleasure. By the wealth and influence of their Guilds, the townsmen position within the Middle Ages society considerably improved. They became influent and powerful, and were able to obtain exemptions from many burdens. By different means, from buying or taking advantage of political instability, they secured more privileges, until the towns became in many cases self-governing communities. Teaching at Paris, Grandes Chroniques de France, late 14th-century , Illuminated manuscript. Many Universities took the Guilds as models, the University of Paris being such an example. The right to teach belonged to the masters, corresponding to the masterworkmen, while the students corresponded to the apprentices. In a guild, an apprentice had to work a number of years and to prove their skills before they became full members. In a similar manner, the students had to study for six years and pass examinations before becoming masters in art.