* Your assessment is very important for improving the work of artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download Document

Focal infection theory wikipedia , lookup

HIV trial in Libya wikipedia , lookup

Transmission (medicine) wikipedia , lookup

Hygiene hypothesis wikipedia , lookup

Infection control wikipedia , lookup

Diseases of poverty wikipedia , lookup

HIV and pregnancy wikipedia , lookup

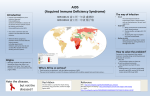

Chronic Care Programme Treatment guidelines HIV/Aids Chronic condition Alternative names Consultations protocols Preferred treating provider Notes preferred as indicated by option referral protocols apply Provider General Practitioner Physician Paediatrician Cardiologist Neurologist Neurosurgeon Maximum consultations per annum Initial consultation Follow-up consultation Tariff codes New Patient Option/plan GMHPP Gold Options G1000, G500 and G200. Blue Options B300 and B200. GMISHPP Existing patient Stable Unstable Controlled Uncontrolled 1 1 3 1 0183; 0142; 0187; 0108 1 5 Investigations protocols ICD 10 coding G40.-G41. General Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome(AIDS) is a set of symptoms and infections resulting from the damage to the human immune system caused by the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV). This condition progressively reduces the effectiveness of the immune system and leaves individuals susceptible to opportunistic infections and tumors. HIV is transmitted through direct contact of a mucous membrane or the bloodstream with a bodily fluid containing HIV, such as blood, semen, vaginal fluid, preseminal fluid, and breast milk. This transmission can involve anal, vaginal or oral sex, blood transfusion, contaminated hypodermic needles, exchange between mother and baby during pregnancy, childbirth, or breastfeeding, or other exposure to one of the above bodily fluids. AIDS is now a pandemic. In 2007, an estimated 33.2 million people lived with the disease worldwide, and it killed an estimated 2.1 million people, including 330,000 children. Over three-quarters of these deaths occurred in sub-Saharan Africa, retarding economic growth and destroying human capital. Most researchers believe that HIV originated in sub-Saharan Africa during the twentieth century. The disease was first identified by the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention in 1981 and its cause identified by American and French scientists in the late 1980s. Although treatments for AIDS and HIV can slow the course of the disease, there is currently no vaccine or cure. Antiretroviral treatment reduces both the mortality and the morbidity of HIV infection, but these drugs are expensive and routine access to antiretroviral medication is not available in all countries. Due to the difficulty in treating HIV infection, preventing infection is a key aim in controlling the AIDS epidemic, with health organizations promoting safe sex and needle-exchange programmes in attempts to slow the spread of the virus Signs and symptoms The symptoms of AIDS are primarily the result of conditions that do not normally develop in individuals with healthy immune systems. Most of these conditions are infections caused by bacteria, viruses, fungi and parasites that are normally controlled by the elements of the immune system that HIV damages. Opportunistic infections are common in people with AIDS. HIV affects nearly every organ system. People with AIDS also have an increased risk of developing various cancers such as Kaposi's sarcoma, cervical cancer and cancers of the immune system known as lymphomas. Additionally, people with AIDS often have systemic symptoms of infection like fevers, sweats (particularly at night), swollen glands, chills, weakness, and weight loss. The specific opportunistic infections that AIDS patients develop depend in part on the prevalence of these infections in the geographic area in which the patient lives. Pulmonary infections X-ray of Pneumocystis jirovecii caused pneumonia. There is increased white (opacity) in the lower lungs on both sides, characteristic of Pneumocystis pneumonia Pneumocystis pneumonia (originally known as Pneumocystis carinii pneumonia, and still abbreviated as PCP, which now stands for Pneumocystis pneumonia) is relatively rare in healthy, immunocompetent people, but common among HIV-infected individuals. It is caused by Pneumocystis jirovecii. Before the advent of effective diagnosis, treatment and routine prophylaxis in Western countries, it was a common immediate cause of death. In developing countries, it is still one of the first indications of AIDS in untested individuals, although it does not generally occur unless the CD4 count is less than 200 cells per µL of blood. Tuberculosis (TB) is unique among infections associated with HIV because it is transmissible to immunocompetent people via the respiratory route, is easily treatable once identified, may occur in early-stage HIV disease, and is preventable with drug therapy. However, multidrug resistance is a potentially serious problem. Even though its incidence has declined because of the use of directly observed therapy and other improved practices in Western countries, this is not the case in developing countries where HIV is most prevalent. In early-stage HIV infection (CD4 count >300 cells per µL), TB typically presents as a pulmonary disease. In advanced HIV infection, TB often presents atypically with extrapulmonary (systemic) disease a common feature. Symptoms are usually constitutional and are not localized to one particular site, often affecting bone marrow, bone, urinary and gastrointestinal tracts, liver, regional lymph nodes, and the central nervous system. Gastrointestinal infections Esophagitis is an inflammation of the lining of the lower end of the esophagus (gullet or swallowing tube leading to the stomach). In HIV infected individuals, this is normally due to fungal (candidiasis) or viral (herpes simplex-1 or cytomegalovirus) infections. In rare cases, it could be due to mycobacteria. Unexplained chronic diarrhea in HIV infection is due to many possible causes, including common bacterial (Salmonella, Shigella, Listeria or Campylobacter) and parasitic infections; and uncommon opportunistic infections such as cryptosporidiosis, microsporidiosis, Mycobacterium avium complex (MAC) and viruses, astrovirus, adenovirus, rotavirus and cytomegalovirus, (the latter as a course of colitis). In some cases, diarrhea may be a side effect of several drugs used to treat HIV, or it may simply accompany HIV infection, particularly during primary HIV infection. It may also be a side effect of antibiotics used to treat bacterial causes of diarrhea (common for Clostridium difficile). In the later stages of HIV infection, diarrhea is thought to be a reflection of changes in the way the intestinal tract absorbs nutrients, and may be an important component of HIV-related wasting. Neurological diseases Toxoplasmosis is a disease caused by the single-celled parasite called Toxoplasma gondii; it usually infects the brain causing toxoplasma encephalitis but it can infect and cause disease in the eyes and lungs. Progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy (PML) is a demyelinating disease, in which the gradual destruction of the myelin sheath covering the axons of nerve cells impairs the transmission of nerve impulses. It is caused by a virus called JC virus which occurs in 70% of the population in latent form, causing disease only when the immune system has been severely weakened, as is the case for AIDS patients. It progresses rapidly, usually causing death within months of diagnosis. AIDS dementia complex (ADC) is a metabolic encephalopathy induced by HIV infection and fueled by immune activation of HIV infected brain macrophages and microglia which secrete neurotoxins of both host and viral origin. Specific neurological impairments are manifested by cognitive, behavioral, and motor abnormalities that occur after years of HIV infection and is associated with low CD4+ T cell levels and high plasma viral loads. Prevalence is 10–20% in Western countries but only 1–2% of HIV infections in India. This difference is possibly due to the HIV subtype in India. Cryptococcal meningitis is an infection of the meninx (the membrane covering the brain and spinal cord) by the fungus Cryptococcus neoformans. It can cause fevers, headache, fatigue, nausea, and vomiting. Patients may also develop seizures and confusion; left untreated, it can be lethal. Tumors and malignancies Kaposi's sarcoma Patients with HIV infection have substantially increased incidence of several malignant cancers. This is primarily due to co-infection with an oncogenic DNA virus, especially Epstein-Barr virus (EBV), Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus (KSHV), and human papillomavirus (HPV). Kaposi's sarcoma (KS) is the most common tumor in HIV-infected patients. The appearance of this tumor in young homosexual men in 1981 was one of the first signals of the AIDS epidemic. Caused by a gammaherpes virus called Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpes virus (KSHV), it often appears as purplish nodules on the skin, but can affect other organs, especially the mouth, gastrointestinal tract, and lungs. High-grade B cell lymphomas such as Burkitt's lymphoma, Burkitt's-like lymphoma, diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL), and primary central nervous system lymphoma present more often in HIV-infected patients. These particular cancers often foreshadow a poor prognosis. In some cases these lymphomas are AIDS-defining. Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) or KSHV cause many of these lymphomas. Cervical cancer in HIV-infected women is considered AIDS-defining. It is caused by human papillomavirus (HPV). In addition to the AIDS-defining tumors listed above, HIV-infected patients are at increased risk of certain other tumors, such as Hodgkin's disease and anal and rectal carcinomas. However, the incidence of many common tumors, such as breast cancer or colon cancer, does not increase in HIV-infected patients. In areas where HAART is extensively used to treat AIDS, the incidence of many AIDS-related malignancies has decreased, but at the same time malignant cancers overall have become the most common cause of death of HIV-infected patients. Other opportunistic infections AIDS patients often develop opportunistic infections that present with non-specific symptoms, especially low-grade fevers and weight loss. These include infection with Mycobacterium aviumintracellulare and cytomegalovirus (CMV). CMV can cause colitis, as described above, and CMV retinitis can cause blindness. Penicilliosis due to Penicillium marneffei is now the third most common opportunistic infection (after extrapulmonary tuberculosis and cryptococcosis) in HIV-positive individuals within the endemic area of Southeast Asia. Diagnosis Scanning electron micrograph of HIV-1, colored green, budding from a cultured lymphocyte. AIDS is the most severe acceleration of infection with HIV. HIV is a retrovirus that primarily infects vital organs of the human immune system such as CD4+ T cells (a subset of T cells), macrophages and dendritic cells. It directly and indirectly destroys CD4+ T cells. Once HIV has killed so many CD4+ T cells that there are fewer than 200 of these cells per microliter (µL) of blood, cellular immunity is lost. Acute HIV infection progresses over time to clinical latent HIV infection and then to early symptomatic HIV infection and later to AIDS, which is identified either on the basis of the amount of CD4+ T cells remaining in the blood, and/or the presence of certain infections, as noted above. In the absence of antiretroviral therapy, the median time of progression from HIV infection to AIDS is nine to ten years, and the median survival time after developing AIDS is only 9.2 months. However, the rate of clinical disease progression varies widely between individuals, from two weeks up to 20 years. Many factors affect the rate of progression. These include factors that influence the body's ability to defend against HIV such as the infected person's general immune function. Older people have weaker immune systems, and therefore have a greater risk of rapid disease progression than younger people. Poor access to health care and the existence of coexisting infections such as tuberculosis also may predispose people to faster disease progression. The infected person's genetic inheritance plays an important role and some people are resistant to certain strains of HIV. An example of this is people with the homozygous CCR5Δ32 variation are resistant to infection with certain strains of HIV. HIV is genetically variable and exists as different strains, which cause different rates of clinical disease progression. Sexual transmission Sexual transmission occurs with the contact between sexual secretions of one person with the rectal, genital or oral mucous membranes of another. Unprotected receptive sexual acts are riskier than unprotected insertive sexual acts, and the risk for transmitting HIV through unprotected anal intercourse is greater than the risk from vaginal intercourse or oral sex. However, oral sex is not entirely safe, as HIV can be transmitted through both insertive and receptive oral sex. The risk of HIV transmission from exposure to saliva is considerably smaller than the risk from exposure to semen, one would have to swallow liters of saliva from a carrier to run a significant risk of becoming infected. Sexual assault greatly increases the risk of HIV transmission as protection is rarely employed and physical trauma to the vagina frequently occurs, facilitating the transmission of HIV. Other sexually transmitted infections (STI) increase the risk of HIV transmission and infection, because they cause the disruption of the normal epithelial barrier by genital ulceration and/or microulceration; and by accumulation of pools of HIV-susceptible or HIV-infected cells (lymphocytes and macrophages) in semen and vaginal secretions. Epidemiological studies from sub-Saharan Africa, Europe and North America suggest that genital ulcers, such as those caused by syphilis and/or chancroid, increase the risk of becoming infected with HIV by about four-fold. There is also a significant although lesser increase in risk from STIs such as gonorrhea, Chlamydial infection and trichomoniasis, which all cause local accumulations of lymphocytes and macrophages. Transmission of HIV depends on the infectiousness of the index case and the susceptibility of the uninfected partner. Infectivity seems to vary during the course of illness and is not constant between individuals. An undetectable plasma viral load does not necessarily indicate a low viral load in the seminal liquid or genital secretions. However, each 10-fold increase in the level of HIV in the blood is associated with an 81% increased rate of HIV transmission. Women are more susceptible to HIV-1 infection due to hormonal changes, vaginal microbial ecology and physiology, and a higher prevalence of sexually transmitted diseases. People who have been infected with one strain of HIV can still be infected later on in their lives by other, more virulent strains. Exposure to blood-borne pathogens This transmission route is particularly relevant to intravenous drug users, hemophiliacs and recipients of blood transfusions and blood products. Sharing and reusing syringes contaminated with HIV-infected blood represents a major risk for infection with HIV. Needle sharing is the cause of one third of all new HIV-infections in North America, China, and Eastern Europe. The risk of being infected with HIV from a single prick with a needle that has been used on an HIVinfected person is thought to be about 1 in 150 (see table above). Post-exposure prophylaxis with anti-HIV drugs can further reduce this risk. This route can also affect people who give and receive tattoos and piercings. Universal precautions are frequently not followed in both subSaharan Africa and much of Asia because of both a shortage of supplies and inadequate training. The WHO estimates that approximately 2.5% of all HIV infections in sub-Saharan Africa are transmitted through unsafe healthcare injections. Because of this, the United Nations General Assembly has urged the nations of the world to implement precautions to prevent HIV transmission by health workers. The risk of transmitting HIV to blood transfusion recipients is extremely low in developed countries where improved donor selection and HIV screening is performed. However, according to the WHO, the overwhelming majority of the world's population does not have access to safe blood and between 5% and 10% of the world's HIV infections come from transfusion of infected blood and blood products. Perinatal transmission The transmission of the virus from the mother to the child can occur in utero during the last weeks of pregnancy and at childbirth. In the absence of treatment, the transmission rate between a mother and her child during pregnancy, labor and delivery is 25%. However, when the mother takes antiretroviral therapy and gives birth by caesarean section, the rate of transmission is just 1%. The risk of infection is influenced by the viral load of the mother at birth, with the higher the viral load, the higher the risk. Breastfeeding also increases the risk of transmission by about 4 %. Misconceptions A number of misconceptions have arisen surrounding HIV/AIDS. Three of the most common are that AIDS can spread through casual contact, that sexual intercourse with a virgin will cure AIDS, and that HIV can infect only homosexual men and drug users. Other misconceptions are that any act of anal intercourse between gay men can lead to AIDS infection, and that open discussion of homosexuality and HIV in schools will lead to increased rates of homosexuality and AIDS. The Pathophysiology. The pathophysiology of AIDS is complex, as is the case with all syndromes. Ultimately, HIV causes AIDS by depleting CD4+ T helper lymphocytes. This weakens the immune system and allows opportunistic infections. T lymphocytes are essential to the immune response and without them, the body cannot fight infections or kill cancerous cells. The mechanism of CD4+ T cell depletion differs in the acute and chronic phases. During the acute phase, HIV-induced cell lysis and killing of infected cells by cytotoxic T cells accounts for CD4+ T cell depletion, although apoptosis may also be a factor. During the chronic phase, the consequences of generalized immune activation coupled with the gradual loss of the ability of the immune system to generate new T cells appear to account for the slow decline in CD4+ T cell numbers. Although the symptoms of immune deficiency characteristic of AIDS do not appear for years after a person is infected, the bulk of CD4+ T cell loss occurs during the first weeks of infection, especially in the intestinal mucosa, which harbors the majority of the lymphocytes found in the body. The reason for the preferential loss of mucosal CD4+ T cells is that a majority of mucosal CD4+ T cells express the CCR5 coreceptor, whereas a small fraction of CD4+ T cells in the bloodstream do so. HIV seeks out and destroys CCR5 expressing CD4+ cells during acute infection. A vigorous immune response eventually controls the infection and initiates the clinically latent phase. However, CD4+ T cells in mucosal tissues remain depleted throughout the infection, although enough remain to initially ward off life-threatening infections. Continuous HIV replication results in a state of generalized immune activation persisting throughout the chronic phase. Immune activation, which is reflected by the increased activation state of immune cells and release of proinflammatory cytokines, results from the activity of several HIV gene products and the immune response to ongoing HIV replication. Another cause is the breakdown of the immune surveillance system of the mucosal barrier caused by the depletion of mucosal CD4+ T cells during the acute phase of disease. This results in the systemic exposure of the immune system to microbial components of the gut’s normal flora, which in a healthy person is kept in check by the mucosal immune system. The activation and proliferation of T cells that results from immune activation provides fresh targets for HIV infection. However, direct killing by HIV alone cannot account for the observed depletion of CD4+ T cells since only 0.01-0.10% of CD4+ T cells in the blood are infected. A major cause of CD4+ T cell loss appears to result from their heightened susceptibility to apoptosis when the immune system remains activated. Although new T cells are continuously produced by the thymus to replace the ones lost, the regenerative capacity of the thymus is slowly destroyed by direct infection of its thymocytes by HIV. Eventually, the minimal number of CD4+ T cells necessary to maintain a sufficient immune response is lost, leading to AIDS Cells affected The virus, entering through which ever route, acts primarily on the following cells: 1. Lymphoreticular system: 1. CD4+ T-Helper cells 2. CD4+ Macrophages 3. CD4+ Monocytes 4. B-lymphocytes 2. Certain endothelial cells 3. Central nervous system: 1. Microglia of the nervous system 2. Astrocytes 3. Oligodendrocytes 4. Neurones - indirectly by the action of cytokines and the gp-120 The effect The virus has cytopathic effects but how it does it is still not quite clear. It can remain inactive in these cells for long periods, though. This effect is hypothesized to be due to the CD4-gp120 interaction. The most prominent effect of the HIV virus is its T-helper cell suppression and lysis. The cell is simply killed off or deranged to the point of being function-less (they do not respond to foreign antigens). The infected B-cells can not produce enough antibodies either. Thus the immune system collapses leading to the familiar AIDS complications, like infections and neoplasms (vide supra). Infection of the cells of the CNS cause acute aseptic meningitis, subacute encephalitis, vacuolar myelopathy and peripheral neuropathy. Later it leads to even AIDS dementia complex. The CD4-gp120 interaction (vide supra) is also permissive to other viruses like Cytomegalovirus, Hepatitis virus, Herpes simplex virus, etc. These viruses lead to further cell damage i.e. cytopathy. Molecular basis For details, see: Structure and genome of HIV, HIV replication cycle HIV tropism Treatment There is currently no vaccine or cure for HIV or AIDS. The only known methods of prevention are based on avoiding exposure to the virus or, failing that, an antiretroviral treatment directly after a highly significant exposure, called post-exposure prophylaxis (PEP). PEP has a very demanding four week schedule of dosage. It also has very unpleasant side effects including diarrhea, malaise, nausea and fatigue. Antiviral therapy Current treatment for HIV infection consists of highly active antiretroviral therapy, or HAART. This has been highly beneficial to many HIV-infected individuals since its introduction in 1996 when the protease inhibitor-based HAART initially became available. Current optimal HAART options consist of combinations (or "cocktails") consisting of at least three drugs belonging to at least two types, or "classes," of antiretroviral agents. Typical regimens consist of two nucleoside analogue reverse transcriptase inhibitors (NARTIs or NRTIs) plus either a protease inhibitor or a non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor (NNRTI). Because HIV disease progression in children is more rapid than in adults, and laboratory parameters are less predictive of risk for disease progression, particularly for young infants, treatment recommendations are more aggressive for children than for adults. In developed countries where HAART is available, doctors assess the viral load, rapidity in CD4 decline, and patient readiness while deciding when to recommend initiating treatment. HAART allows the stabilization of the patient’s symptoms and viremia, but it neither cures the patient of HIV, nor alleviates the symptoms, and high levels of HIV-1, often HAART resistant, return once treatment is stopped. Moreover, it would take more than the lifetime of an individual to be cleared of HIV infection using HAART. Despite this, many HIV-infected individuals have experienced remarkable improvements in their general health and quality of life, which has led to the plummeting of HIV-associated morbidity and mortality. In the absence of HAART, progression from HIV infection to AIDS occurs at a median of between nine to ten years and the median survival time after developing AIDS is only 9.2 months. HAART is thought to increase survival time by between 4 and 12 years. For some patients, which can be more than fifty percent of patients, HAART achieves far less than optimal results, due to medication intolerance/side effects, prior ineffective antiretroviral therapy and infection with a drug-resistant strain of HIV. Non-adherence and non-persistence with therapy are the major reasons why some people do not benefit from HAART. The reasons for non-adherence and non-persistence are varied. Major psychosocial issues include poor access to medical care, inadequate social supports, psychiatric disease and drug abuse. HAART regimens can also be complex and thus hard to follow, with large numbers of pills taken frequently. Side effects can also deter people from persisting with HAART, these include lipodystrophy, dyslipidaemia, diarrhoea, insulin resistance, an increase in cardiovascular risks and birth defects. Anti-retroviral drugs are expensive, and the majority of the world's infected individuals do not have access to medications and treatments for HIV and AIDS. Future research It has been postulated that only a vaccine can halt the pandemic because a vaccine would possibly cost less, thus being affordable for developing countries, and would not require daily treatments. However, even after almost 30 years of research, HIV-1 remains a difficult target for a vaccine. Research to improve current treatments includes decreasing side effects of current drugs, further simplifying drug regimens to improve adherence, and determining the best sequence of regimens to manage drug resistance. A number of studies have shown that measures to prevent opportunistic infections can be beneficial when treating patients with HIV infection or AIDS. Vaccination against hepatitis A and B is advised for patients who are not infected with these viruses and are at risk of becoming infected. Patients with substantial immunosuppression are also advised to receive prophylactic therapy for Pneumocystis jiroveci pneumonia (PCP), and many patients may benefit from prophylactic therapy for toxoplasmosis and Cryptococcus meningitis as well. Alternative medicine Various forms of alternative medicine have been used to treat symptoms or alter the course of the disease. Acupuncture has been used to alleviate some symptoms, such peripheral neuropathy, but cannot cure the HIV infection. Several randomized clinical trials testing the effect of herbal medicines have shown that there is no evidence that these herbs have any effect on the progression of the disease, but may instead produce serious side-effects. Some data suggest that multivitamin and mineral supplements might reduce HIV disease progression in adults, although there is no conclusive evidence on if they reduce mortality among people with good nutritional status. Vitamin A supplementation in children probably has some benefit. Daily doses of selenium can suppress HIV viral burden with an associated improvement of the CD4 count. Selenium can be used as an adjunct therapy to standard antiviral treatments, but cannot itself reduce mortality and morbidity. Current studies indicate that that alternative medicine therapies have little effect on the mortality or morbidity of the disease, but may improve the quality of life of individuals afflicted with AIDS. The psychological benefits of these therapies are the most important use Medicine formularies Plan or option GMHPP Gold Options G1000, G500 and G200 Blue Options B300 and B200 GMISHPP Blue Option B100 [Link to appropriate Mediscor formulary] [Core] n/a Epidemiology The AIDS pandemic can also be seen as several epidemics of separate subtypes; the major factors in its spread are sexual transmission and vertical transmission from mother to child at birth and through breast milk. Despite recent, improved access to antiretroviral treatment and care in many regions of the world, the AIDS pandemic claimed an estimated 2.1 million (range 1.9– 2.4 million) lives in 2007 of which an estimated 330,000 were children under 15 years. Globally, an estimated 33.2 million people lived with HIV in 2007, including 2.5 million children. An estimated 2.5 million (range 1.8–4.1 million) people were newly infected in 2007, including 420,000 children. Sub-Saharan Africa remains by far the worst affected region. In 2007 it contained an estimated 68% of all people living with AIDS and 76% of all AIDS deaths, with 1.7 million new infections bringing the number of people living with HIV to 22.5 million, and with 11.4 million AIDS orphans living in the region. Unlike other regions, most people living with HIV in sub-Saharan Africa in 2007 (61%) were women. Adult prevalence in 2007 was an estimated 5.0%, and AIDS continued to be the single largest cause of mortality in this region. South Africa has the largest population of HIV patients in the world, followed by Nigeria and India. South & South East Asia are second worst affected; in 2007 this region contained an estimated 18% of all people living with AIDS, and an estimated 300,000 deaths from AIDS. India has an estimated 2.5 million infections and an estimated adult prevalence of 0.36%. Life expectancy has fallen dramatically in the worst-affected countries; for example, in 2006 it was estimated that it had dropped from 65 to 35 years in Botswana. Prognosis Without treatment, the net median survival time after infection with HIV is estimated to be 9 to 11 years, depending on the HIV subtype, and the median survival rate after diagnosis of AIDS in resource-limited settings where treatment is not available ranges between 6 and 19 months, depending on the study. In areas where it is widely available, the development of HAART as effective therapy for HIV infection and AIDS reduced the death rate from this disease by 80%, and raised the life expectancy for a newly-diagnosed HIV-infected person to about 20 years. As new treatments continue to be developed and because HIV continues to evolve resistance to treatments, estimates of survival time are likely to continue to change. Without antiretroviral therapy, death normally occurs within a year. Most patients die from opportunistic infections or malignancies associated with the progressive failure of the immune system. The rate of clinical disease progression varies widely between individuals and has been shown to be affected by many factors such as host susceptibility and immune function health care and co-infections, as well as which particular strain of the virus is involved References 1. Weiss RA (May 1993). "How does HIV cause AIDS?" Science (journal) 260 (5112): 1273–9. PMID 8493571. 2. Divisions of HIV/AIDS Prevention (2003). HIV and Its Transmission. Centers for Disease Control & Prevention. Retrieved on 2006-05-23. 3. San Francisco AIDS Foundation (2006-04-14). How HIV is spread. Retrieved on 200605-23. 4. Kallings LO (2008). "The first postmodern pandemic: 25 years of HIV/AIDS". J Intern Med 263 (3): 218–43. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2796.2007.01910.x. PMID 18205765. 5. UNAIDS, WHO (December 2007). 2007 AIDS epidemic update (PDF). Retrieved on 2008-03-12. 6. Bell C, Devarajan S, Gersbach H (2003). "The long-run economic costs of AIDS: theory and an application to South Africa" (PDF). World Bank Policy Research Working Paper No. 3152. Retrieved on 2008-04-28. 7. Gao F, Bailes E, Robertson DL, et al (1999). "Origin of HIV-1 in the Chimpanzee Pan troglodytes troglodytes". Nature 397 (6718): 436–441. doi:10.1038/17130. PMID 9989410. 8. Gallo RC (2006). "A reflection on HIV/AIDS research after 25 years". Retrovirology 3: 72. doi:10.1186/1742-4690-3-72. PMID 17054781. 9. Palella FJ Jr, Delaney KM, Moorman AC, et al (1998). "Declining morbidity and mortality among patients with advanced human immunodeficiency virus infection. HIV Outpatient Study Investigators". N. Engl. J. Med 338 (13): 853–860. PMID 9516219. 10. Holmes CB, Losina E, Walensky RP, Yazdanpanah Y, Freedberg KA (2003). "Review of human immunodeficiency virus type 1-related opportunistic infections in sub-Saharan Africa". Clin. Infect. Dis. 36 (5): 656–662. PMID 12594648. 11. Guss DA (1994). "The acquired immune deficiency syndrome: an overview for the emergency physician, Part 1". J. Emerg. Med. 12 (3): 375–384. PMID 8040596. 12. Guss DA (1994). "The acquired immune deficiency syndrome: an overview for the emergency physician, Part 2". J. Emerg. Med. 12 (4): 491–497. PMID 7963396. 13. Feldman C (2005). "Pneumonia associated with HIV infection". Curr. Opin. Infect. Dis. 18 (2): 165–170. PMID 15735422. 14. Decker CF, Lazarus A (2000). "Tuberculosis and HIV infection. How to safely treat both disorders concurrently". Postgrad Med. 108 (2): 57–60, 65–68. PMID 10951746. 15. Zaidi SA, Cervia JS (2002). "Diagnosis and management of infectious esophagitis associated with human immunodeficiency virus infection". J. Int. Assoc. Physicians AIDS Care (Chic Ill) 1 (2): 53–62. PMID 12942677. 16. Pollok RC (2001). "Viruses causing diarrhoea in AIDS". Novartis Found. Symp. 238: 276–83; discussion 283–8. PMID 11444032. 17. Guerrant RL, Hughes JM, Lima NL, Crane J (1990). "Diarrhea in developed and developing countries: magnitude, special settings, and etiologies". Rev. Infect. Dis. 12 (Suppl 1): S41–S50. PMID 2406855. 18. Luft BJ, Chua A (2000). "Central Nervous System Toxoplasmosis in HIV Pathogenesis, Diagnosis, and Therapy". Curr. Infect. Dis. Rep. 2 (4): 358–362. PMID 11095878. 19. Sadler M, Nelson MR (1997). "Progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy in HIV". Int. J. STD AIDS 8 (6): 351–357. PMID 9179644. 20. Gray F, Adle-Biassette H, Chrétien F, Lorin de la Grandmaison G, Force G, Keohane C (2001). "Neuropathology and neurodegeneration in human immunodeficiency virus infection. Pathogenesis of HIV-induced lesions of the brain, correlations with HIVassociated disorders and modifications according to treatments". Clin. Neuropathol. 20 (4): 146–155. PMID 11495003. 21. Grant I, Sacktor H, McArthur J (2005). "HIV neurocognitive disorders", in H. E. Gendelman, I. Grant, I. Everall, S. A. Lipton, and S. Swindells. (ed.): The Neurology of AIDS (PDF), 2nd, London, UK: Oxford University Press, 357–373. ISBN 0-19-852610-5. 22. Satishchandra P, Nalini A, Gourie-Devi M, et al (2000). "Profile of neurologic disorders associated with HIV/AIDS from Bangalore, South India (1989–1996)". Indian J. Med. Res. 11: 14–23. PMID 10793489. 23. Wadia RS, Pujari SN, Kothari S, Udhar M, Kulkarni S, Bhagat S, Nanivadekar A (2001). "Neurological manifestations of HIV disease". J. Assoc. Physicians India 49: 343–348. PMID 11291974. 24. Boshoff C, Weiss R (2002). "AIDS-related malignancies". Nat. Rev. Cancer 2 (5): 373– 382. PMID 12044013. 25. Yarchoan R, Tosatom G, Littlem RF (2005). "Therapy insight: AIDS-related malignancies — the influence of antiviral therapy on pathogenesis and management". Nat. Clin. Pract. Oncol. 2 (8): 406–415. PMID 16130937. 26. Palefsky J (2007). "Human papillomavirus infection in HIV-infected persons". Top HIV Med 15 (4): 130–3. PMID 17720998. 27. Bonnet F, Lewden C, May T, et al (2004). "Malignancy-related causes of death in human immunodeficiency virus-infected patients in the era of highly active antiretroviral therapy". Cancer 101 (2): 317–324. PMID 15241829. 28. Skoulidis F, Morgan MS, MacLeod KM (2004). "Penicillium marneffei: a pathogen on our doorstep?". J. R. Soc. Med. 97 (2): 394–396. PMID 15286196. 29. Alimonti JB, Ball TB, Fowke KR (2003). "Mechanisms of CD4+ T lymphocyte cell death in human immunodeficiency virus infection and AIDS.". J. Gen. Virol. 84 (7): 1649– 1661. doi:10.1099/vir.0.19110-0. PMID 12810858. 30. (2003) An Atlas of Differential Diagnosis in HIV Disease, Second Edition. CRC PressParthenon Publishers, 22-27. ISBN 1-84214-026-4. 31. Morgan D, Mahe C, Mayanja B, Okongo JM, Lubega R, Whitworth JA (2002). "HIV-1 infection in rural Africa: is there a difference in median time to AIDS and survival compared with that in industrialized countries?". AIDS 16 (4): 597–632. PMID 11873003. 32. Clerici M, Balotta C, Meroni L, et al (1996). "Type 1 cytokine production and low prevalence of viral isolation correlate with long-term non progression in HIV infection". AIDS Res. Hum. Retroviruses. 12 (11): 1053–1061. PMID 8827221. 33. Morgan D, Mahe C, Mayanja B, Whitworth JA (2002). "Progression to symptomatic disease in people infected with HIV-1 in rural Uganda: prospective cohort study". BMJ 324 (7331): 193–196. doi:10.1136/bmj.324.7331.193. PMID 11809639. 34. Gendelman HE, Phelps W, Feigenbaum L, et al (1986). "Transactivation of the human immunodeficiency virus long terminal repeat sequences by DNA viruses". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 83 (24): 9759–9763. PMID 2432602. 35. Bentwich Z, Kalinkovich, A, Weisman Z (1995). "Immune activation is a dominant factor in the pathogenesis of African AIDS.". Immunol. Today 16 (4): 187–191. PMID 7734046. 36. Tang J, Kaslow RA (2003). "The impact of host genetics on HIV infection and disease progression in the era of highly active antiretroviral therapy". AIDS 17 (Suppl 4): S51– S60. PMID 15080180. 37. Quiñones-Mateu ME, Mas A, Lain de Lera T, Soriano V, Alcami J, Lederman MM, Domingo E (1998). "LTR and tat variability of HIV-1 isolates from patients with divergent rates of disease progression". Virus Research 57 (1): 11–20. PMID 9833881. 38. Campbell GR, Pasquier E, Watkins J, et al (2004). "The glutamine-rich region of the HIV1 Tat protein is involved in T-cell apoptosis". J. Biol. Chem. 279 (46): 48197–48204. doi:10.1074/jbc.M406195200. PMID 15331610. 39. Kaleebu P, French N, Mahe C, et al (2002). "Effect of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) type 1 envelope subtypes A and D on disease progression in a large cohort of HIV1-positive persons in Uganda". J. Infect. Dis. 185 (9): 1244–1250. PMID 12001041. 40. Rothenberg RB, Scarlett M, del Rio C, Reznik D, O'Daniels C (1998). "Oral transmission of HIV". AIDS 12 (16): 2095–2105. PMID 9833850. 41. Mastro TD, de Vincenzi I (1996). "Probabilities of sexual HIV-1 transmission". AIDS 10 (Suppl A): S75–S82. PMID 8883613. 42. Koenig MA, Zablotska I, Lutalo T, Nalugoda F, Wagman J, Gray R (2004). "Coerced first intercourse and reproductive health among adolescent women in Rakai, Uganda". Int Fam Plan Perspect 30 (4): 156–63. doi:10.1363/ifpp.30.156.04. PMID 15590381. 43. Laga M, Nzila N, Goeman J (1991). "The interrelationship of sexually transmitted diseases and HIV infection: implications for the control of both epidemics in Africa". AIDS 5 (Suppl 1): S55–S63. PMID 1669925. 44. Tovanabutra S, Robison V, Wongtrakul J, et al (2002). "Male viral load and heterosexual transmission of HIV-1 subtype E in northern Thailand". J. Acquir. Immune. Defic. Syndr. 29 (3): 275–283. PMID 11873077. 45. Sagar M, Lavreys L, Baeten JM, et al (2004). "Identification of modifiable factors that affect the genetic diversity of the transmitted HIV-1 population". AIDS 18 (4): 615–619. PMID 15090766. 46. Lavreys L, Baeten JM, Martin HL, et al (March 2004). "Hormonal contraception and risk of HIV-1 acquisition: results of a 10-year prospective study". AIDS 18 (4): 695–7. PMID 15090778. 47. Fan H (2005). in Fan, H., Conner, R. F. and Villarreal, L. P. eds: AIDS: science and society, 4th, Boston, MA: Jones and Bartlett Publishers. ISBN 0-7637-0086-X. 48. WHO, UNAIDS Reaffirm HIV as a Sexually Transmitted Disease. WHO (2003-03-17). Retrieved on 2006-01-17. 49. Financial Resources Required to Achieve, Universal Access to HIV Prevention, Treatment Care and Support (pdf). UNAIDS. Retrieved on 2008-04-11. 50. Blood safety....for too few. WHO (2001). Retrieved on 2006-01-17. 51. Coovadia H (2004). "Antiretroviral agents—how best to protect infants from HIV and save their mothers from AIDS". N. Engl. J. Med. 351 (3): 289–292. PMID 15247337. 52. Coovadia HM, Bland RM (2007). "Preserving breastfeeding practice through the HIV pandemic". Trop. Med. Int. Health. 12 (9): 1116–1133. PMID 17714431. 53. Blechner MJ (1997). Hope and mortality: psychodynamic approaches to AIDS and HIV. Hillsdale, NJ: Analytic Press. ISBN 0-88163-223-6. 54. Guss DA (1994). "The acquired immune deficiency syndrome: an overview for the emergency physician, Part 1". J Emerg Med 12 (3): 375–84. PMID 8040596. 55. Hel Z, McGhee JR, Mestecky J (June 2006). "HIV infection: first battle decides the war". Trends Immunol. 27 (6): 274–81. doi:10.1016/j.it.2006.04.007. PMID 16679064. 56. Mehandru S, Poles MA, Tenner-Racz K, Horowitz A, Hurley A, Hogan C, Boden D, Racz P, Markowitz M (September 2004). "Primary HIV-1 infection is associated with preferential depletion of CD4+ T lymphocytes from effector sites in the gastrointestinal tract". J. Exp. Med. 200 (6): 761–70. doi:10.1084/jem.20041196. PMID 15365095. 57. Brenchley JM, Schacker TW, Ruff LE, Price DA, Taylor JH, Beilman GJ, Nguyen PL, Khoruts A, Larson M, Haase AT, Douek DC (September 2004). "CD4+ T cell depletion during all stages of HIV disease occurs predominantly in the gastrointestinal tract". J. Exp. Med. 200 (6): 749–59. doi:10.1084/jem.20040874. PMID 15365096. 58. Appay V, Sauce D (January 2008). "Immune activation and inflammation in HIV-1 infection: causes and consequences". J. Pathol. 214 (2): 231–41. doi:10.1002/path.2276. PMID 18161758. 59. Brenchley JM, Price DA, Schacker TW, Asher TE, Silvestri G, Rao S, Kazzaz Z, Bornstein E, Lambotte O, Altmann D, Blazar BR, Rodriguez B, Teixeira-Johnson L, Landay A, Martin JN, Hecht FM, Picker LJ, Lederman MM, Deeks SG, Douek DC (December 2006). "Microbial translocation is a cause of systemic immune activation in chronic HIV infection". Nat. Med. 12 (12): 1365–71. doi:10.1038/nm1511. PMID 17115046. 60. Textbook of Pathology by Harsh Mohan, ISBN 81-8061-368-2 61. Textbook of Pathology by Harsh Mohan, ISBN 81-8061-368-2 62. World Health Organization (1990). "Interim proposal for a WHO staging system for HIV infection and disease". WHO Wkly Epidem. Rec. 65 (29): 221–228. PMID 1974812. 63. Centers for Disease Control (CDC) (1982). "Persistent, generalized lymphadenopathy among homosexual males.". MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 31 (19): 249–251. PMID 6808340. 64. Barré-Sinoussi F, Chermann JC, Rey F, et al (1983). "Isolation of a T-lymphotropic retrovirus from a patient at risk for acquired immune deficiency syndrome (AIDS)". Science 220 (4599): 868–871. doi:10.1126/science.6189183. PMID 6189183. 65. 1993 Revised Classification System for HIV Infection and Expanded Surveillance Case Definition for AIDS Among Adolescents and Adults. CDC (1992). Retrieved on 2006-0209. 66. Kumaranayake L, Watts C (2001). "Resource allocation and priority setting of HIV/AIDS interventions: addressing the generalized epidemic in sub-Saharan Africa". J. Int. Dev. 13 (4): 451–466. doi:10.1002/jid.798. 67. Weber B (2006). "Screening of HIV infection: role of molecular and immunological assays". Expert Rev. Mol. Diagn. 6 (3): 399–411. doi:10.1586/14737159.6.3.399. PMID 16706742. 68. Tóth FD, Bácsi A, Beck Z, Szabó J (2001). "Vertical transmission of human immunodeficiency virus". Acta Microbiol Immunol Hung 48 (3-4): 413–27. doi:10.1556/AMicr.48.2001.3-4.10. PMID 11791341. 69. Smith DK, Grohskopf LA, Black RJ, et al (2005). "Antiretroviral Postexposure Prophylaxis After Sexual, Injection-Drug Use, or Other Nonoccupational Exposure to HIV in the United States". MMWR 54 (RR02): 1–20. 70. Donegan E, Stuart M, Niland JC, et al (1990). "Infection with human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) among recipients of antibody-positive blood donations". Ann. Intern. Med. 113 (10): 733–739. PMID 2240875. 71. Kaplan EH, Heimer R (1995). "HIV incidence among New Haven needle exchange participants: updated estimates from syringe tracking and testing data". J. Acquir. Immune Defic. Syndr. Hum. Retrovirol. 10 (2): 175–176. PMID 7552482. 72. Bell DM (1997). "Occupational risk of human immunodeficiency virus infection in healthcare workers: an overview.". Am. J. Med. 102 (5B): 9–15. PMID 9845490. 73. European Study Group on Heterosexual Transmission of HIV (1992). "Comparison of female to male and male to female transmission of HIV in 563 stable couples". BMJ. 304 (6830): 809–813. PMID 1392708. 74. Varghese B, Maher JE, Peterman TA, Branson BM,Steketee RW (2002). "Reducing the risk of sexual HIV transmission: quantifying the per-act risk for HIV on the basis of choice of partner, sex act, and condom use". Sex. Transm. Dis. 29 (1): 38–43. PMID 11773877. 75. Leynaert B, Downs AM, de Vincenzi I (1998). "Heterosexual transmission of human immunodeficiency virus: variability of infectivity throughout the course of infection. European Study Group on Heterosexual Transmission of HIV". Am. J. Epidemiol. 148 (1): 88–96. PMID 9663408. 76. Facts about AIDS & HIV. avert.org. Retrieved on 2007-11-30. 77. Johnson AM, Laga M (1988). "Heterosexual transmission of HIV". AIDS 2 (suppl. 1): S49-S56. PMID 3130121. 78. N'Galy B, Ryder RW (1988). "Epidemiology of HIV infection in Africa". Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes 1 (6): 551-558. PMID 3225742. 79. Deschamps MM, Pape JW, Hafner A, Johnson WD Jr. (1996). "Heterosexual transmission of HIV in Haiti". Annals of Internal Medicine 125 (4): 324–330. PMID 8678397. 80. Cayley WE Jr. (2004). "Effectiveness of condoms in reducing heterosexual transmission of HIV". Am. Fam. Physician 70 (7): 1268–1269. PMID 15508535. 81. Module 5/Guidelines for Educators (Microsoft Word). Durex. Retrieved on 2006-04-17. 82. PATH (2006). "The female condom: significant potential for STI and pregnancy prevention". Outlook 22 (2). 83. Condom Facts and Figures. WHO (August 2003). Retrieved on 2006-01-17. 84. Dias SF, Matos MG, Goncalves, A. C. (2005). "Preventing HIV transmission in adolescents: an analysis of the Portuguese data from the Health Behaviour School-aged Children study and focus groups". Eur. J. Public Health 15 (3): 300–304. PMID 15941747. 85. Weiss HA (February 2007). "Male circumcision as a preventive measure against HIV and other sexually transmitted diseases". Curr. Opin. Infect. Dis. 20 (1): 66–72. doi:10.1097/QCO.0b013e328011ab73. PMID 17197884. 86. Eaton LA, Kalichman S (December 2007). "Risk compensation in HIV prevention: implications for vaccines, microbicides, and other biomedical HIV prevention technologies". Curr HIV/AIDS Rep 4 (4): 165–72. doi:10.1007/s11904-007-0024-7. PMID 18366947. 87. Recommendations for Prevention of HIV Transmission in Health-Care Settings. Retrieved on 2008-04-28. 88. Kerr T, Kimber J, Debeck K, Wood E (December 2007). "The role of safer injection facilities in the response to HIV/AIDS among injection drug users". Curr HIV/AIDS Rep 4 (4): 158–64. doi:10.1007/s11904-007-0023-8. PMID 18366946. 89. Wodak A, Cooney A (2006). "Do needle syringe programs reduce HIV infection among injecting drug users: a comprehensive review of the international evidence". Subst Use Misuse 41 (6-7): 777–813. doi:10.1080/10826080600669579. PMID 16809167. 90. WHO HIV and Infant Feeding Technical Consultation (2006). Consensus statement (PDF). Retrieved on 2008-03-12. 91. Hamlyn E, Easterbrook P (August 2007). "Occupational exposure to HIV and the use of post-exposure prophylaxis". Occup Med (Lond) 57 (5): 329–36. doi:10.1093/occmed/kqm046. PMID 17656498. 92. A Pocket Guide to Adult HIV/AIDS Treatment February 2006 edition. Department of Health and Human Services (February 2006). Retrieved on 2006-09-01. 93. A Pocket Guide to Adult HIV/AIDS Treatment February 2006 edition. Department of Health and Human Services (February 2006). Retrieved on 2006-09-01. 94. Guidelines for the Use of Antiretroviral Agents in Pediatric HIV Infection (PDF). Department of Health and Human Services Working Group on Antiretroviral Therapy and Medical Management of HIV-Infected Children (2005-11-03). Retrieved on 2006-01-17. 95. Guidelines for the Use of Antiretroviral Agents in HIV-1-Infected Adults and Adolescents (PDF). Department of Health and Human Services Panel on Clinical Practices for Treatment of HIV Infection (2005-10-06). Retrieved on 2006-01-17. 96. Martinez-Picado J, DePasquale MP, Kartsonis N, et al (2000). "Antiretroviral resistance during successful therapy of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 infection". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 97 (20): 10948–10953. PMID 11005867. 97. Dybul M, Fauci AS, Bartlett JG, Kaplan JE, Pau AK; Panel on Clinical Practices for Treatment of HIV. (2002). "Guidelines for using antiretroviral agents among HIV-infected adults and adolescents". Ann. Intern. Med. 137 (5 Pt 2): 381–433. PMID 12617573. 98. Blankson JN, Persaud D, Siliciano RF (2002). "The challenge of viral reservoirs in HIV-1 infection". Annu. Rev. Med. 53: 557–593. PMID 11818490. 99. Palella FJ, Delaney KM, Moorman AC, Loveless MO, Fuhrer J, Satten GA, Aschman DJ, Holmberg SD (1998). "Declining morbidity and mortality among patients with advanced human immunodeficiency virus infection". N. Engl. J. Med. 338 (13): 853–860. PMID 9516219. 100. Wood E, Hogg RS, Yip B, Harrigan PR, O'Shaughnessy MV, Montaner JS (2003). "Is there a baseline CD4 cell count that precludes a survival response to modern antiretroviral therapy?". AIDS 17 (5): 711–720. PMID 12646794. 101. Chene G, Sterne JA, May M, Costagliola D, Ledergerber B, Phillips AN, Dabis F, Lundgren J, D'Arminio Monforte A, de Wolf F, Hogg R, Reiss P, Justice A, Leport C, Staszewski S, Gill J, Fatkenheuer G, Egger ME and the Antiretroviral Therapy Cohort Collaboration (2003). "Prognostic importance of initial response in HIV-1 infected patients starting potent antiretroviral therapy: analysis of prospective studies". Lancet 362 (9385): 679–686. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(03)14229-8. PMID 12957089. 102. King JT, Justice AC, Roberts MS, Chang CH, Fusco JS and the CHORUS Program Team (2003). "Long-Term HIV/AIDS Survival Estimation in the Highly Active Antiretroviral Therapy Era". Medical Decision Making 23 (1): 9–20. PMID 12583451. 103. Tassie JM, Grabar S, Lancar R, Deloumeaux J, Bentata M, Costagliola D and the Clinical Epidemiology Group from the French Hospital Database on HIV (2002). "Time to AIDS from 1992 to 1999 in HIV-1-infected subjects with known date of infection". Journal of acquired immune deficiency syndromes 30 (1): 81–7. PMID 12048367. 104. Becker SL, Dezii CM, Burtcel B, Kawabata H, Hodder S. (2002). "Young HIVinfected adults are at greater risk for medication nonadherence". MedGenMed. 4 (3): 21. PMID 12466764. 105. Nieuwkerk P, Sprangers M, Burger D, Hoetelmans RM, Hugen PW, Danner SA, van Der Ende ME, Schneider MM, Schrey G, Meenhorst PL, Sprenger HG, Kauffmann RH, Jambroes M, Chesney MA, de Wolf F, Lange JM and the ATHENA Project (2001). "Limited Patient Adherence to Highly Active Antiretroviral Therapy for HIV-1 Infection in an Observational Cohort Study". Arch. Intern. Med. 161 (16): 1962–1968. PMID 11525698. 106. Kleeberger C, Phair J, Strathdee S, Detels R, Kingsley L, Jacobson LP (2001). "Determinants of Heterogeneous Adherence to HIV-Antiretroviral Therapies in the Multicenter AIDS Cohort Study". J. Acquir. Immune Defic. Syndr. 26 (1): 82–92. PMID 11176272. 107. Heath KV, Singer J, O'Shaughnessy MV, Montaner JS, Hogg RS (2002). "Intentional Nonadherence Due to Adverse Symptoms Associated With Antiretroviral Therapy". J. Acquir. Immune Defic. Syndr. 31 (2): 211–217. PMID 12394800. 108. Burgoyne RW, Tan DH (March 2008). "Prolongation and quality of life for HIVinfected adults treated with highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART): a balancing act". J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 61 (3): 469–73. doi:10.1093/jac/dkm499. PMID 18174196. 109. Karlsson Hedestam GB, Fouchier RA, Phogat S, Burton DR, Sodroski J, Wyatt RT (February 2008). "The challenges of eliciting neutralizing antibodies to HIV-1 and to influenza virus". Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 6 (2): 143–55. doi:10.1038/nrmicro1819. PMID 18197170. 110. Laurence J (2006). "Hepatitis A and B virus immunization in HIV-infected persons". AIDS Reader 16 (1): 15–17. PMID 16433468. 111. Power R, Gore-Felton C, Vosvick M, Israelski DM, Spiegel D (June 2002). "HIV: effectiveness of complementary and alternative medicine". Prim. Care 29 (2): 361–78. PMID 12391716. Retrieved on 2008-04-28. 112. Nicholas PK, Kemppainen JK, Canaval GE, et al (February 2007). "Symptom management and self-care for peripheral neuropathy in HIV/AIDS". AIDS Care 19 (2): 179–89. doi:10.1080/09540120600971083. PMID 17364396. Retrieved on 2008-04-28. 113. Liu JP, Manheimer E, Yang M (2005). "Herbal medicines for treating HIV infection and AIDS". Cochrane Database Syst Rev (3): CD003937. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD003937.pub2. PMID 16034917. Retrieved on 2008-04-28. 114. Irlam JH, Visser ME, Rollins N, Siegfried N (2005). "Micronutrient supplementation in children and adults with HIV infection". Cochrane Database Syst Rev (4): CD003650. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD003650.pub2. PMID 16235333. 115. Hurwitz BE, Klaus JR, Llabre MM, et al (January 2007). "Suppression of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 viral load with selenium supplementation: a randomized controlled trial". Arch. Intern. Med. 167 (2): 148–54. doi:10.1001/archinte.167.2.148. PMID 17242315. Retrieved on 2008-04-28. 116. McNeil DG Jr. "U.N. agency to say it overstated extent of H.I.V. cases by millions", New York Times, 2007-11-20. Retrieved on 2008-03-18. 117. Zwahlen M, Egger M (2006). "Progression and mortality of untreated HIVpositive individuals living in resource-limited settings: update of literature review and evidence synthesis" (PDF). UNAIDS Obligation HQ/05/422204. Retrieved on 2008-0319. 118. Knoll B, Lassmann B, Temesgen Z (2007). "Current status of HIV infection: a review for non-HIV-treating physicians". Int J Dermatol 46 (12): 1219–28. doi:10.1111/j.1365-4632.2007.03520.x. PMID 18173512. 119. Lawn SD (2004). "AIDS in Africa: the impact of coinfections on the pathogenesis of HIV-1 infection". J. Infect. Dis. 48 (1): 1–12. PMID 14667787. 120. Campbell GR, Watkins JD, Esquieu D, Pasquier E, Loret EP, Spector SA (2005). "The C terminus of HIV-1 Tat modulates the extent of CD178-mediated apoptosis of T cells". J. Biol. Chem. 280 (46): 38376–39382. PMID 16155003. 121. Senkaali D, Muwonge R, Morgan D, Yirrell D, Whitworth J, Kaleebu P (2005). "The relationship between HIV type 1 disease progression and V3 serotype in a rural Ugandan cohort". AIDS Res. Hum. Retroviruses. 20 (9): 932–937. PMID 15585080. 122. Gottlieb MS (2006). "Pneumocystis pneumonia--Los Angeles. 1981". Am J Public Health 96 (6): 980–1; discussion 982–3. PMID 16714472. 123. Centers for Disease Control (CDC) (1982). "Opportunistic infections and Kaposi's sarcoma among Haitians in the United States". MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 31 (26): 353–354; 360–361. PMID 6811853. 124. Altman LK. "New homosexual disorder worries officials", The New York Times, 1982-05-11. 125. Kher U. "A Name for the Plague", Time, 1982-07-27. Retrieved on 2008-03-10. 126. Centers for Disease Control (CDC) (1982). "Update on acquired immune deficiency syndrome (AIDS)—United States.". MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 31 (37): 507–508; 513–514. PMID 6815471. 127. Curtis T. "The origin of AIDS", Rolling Stone, pp. 54–59, 61, 106, 108. Retrieved on 2008-03-10. 128. Hooper E (1999). The River : A Journey to the Source of HIV and AIDS, 1st, Boston, MA: Little Brown & Co, 1–1070. ISBN 0-316-37261-7. 129. Worobey M, Santiago ML, Keele BF, et al (2004). "Origin of AIDS: contaminated polio vaccine theory refuted". Nature 428 (6985): 820. doi:10.1038/428820a. PMID 15103367. 130. Berry N, Jenkins A, Martin J, et al (2005). "Mitochondrial DNA and retroviral RNA analyses of archival oral polio vaccine (OPV CHAT) materials: evidence of macaque nuclear sequences confirms substrate identity". Vaccine 23: 1639–1648. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2004.10.038. PMID 15705467. 131. Oral Polio Vaccine and HIV / AIDS: Questions and Answers. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2004-03-23). Retrieved on 2006-11-20. 132. Gilbert MT, Rambaut A, Wlasiuk G, Spira TJ, Pitchenik AE, Worobey M (2007). "The emergence of HIV/AIDS in the Americas and beyond". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 104 (47): 18566–70. doi:10.1073/pnas.0705329104. PMID 17978186. 133. (2006) "The impact of AIDS on people and societies", 2006 Report on the global AIDS epidemic (PDF), UNAIDS. Retrieved on 2006-06-14. 134. Ogden J, Nyblade L (2005). Common at its core: HIV-related stigma across contexts (PDF). International Center for Research on Women. Retrieved on 2007-02-15. 135. Herek GM, Capitanio JP (1999). "AIDS Stigma and sexual prejudice" (PDF). American Behavioral Scientist 42 (7): 1130-1147. doi:10.1177/0002764299042007006. Retrieved on 2006-03-27. 136. Snyder M, Omoto AM, Crain AL (1999). "Punished for their good deeds: stigmatization for AIDS volunteers". American Behavioral Scientist 42 (7): 1175–1192. doi:10.1177/0002764299042007009. 137. Herek GM, Capitanio JP, Widaman KF (2002). "HIV-related stigma and knowledge in the United States: prevalence and trends, 1991-1999". Am J Public Health 92 (3): 371–7. PMID 11867313. Retrieved on 2008-03-10. 138. Greener R (2002). "AIDS and macroeconomic impact", in S, Forsyth (ed.): State of The Art: AIDS and Economics. IAEN, 49–55. 139. Over M (1992). "The macroeconomic impact of AIDS in Sub-Saharan Africa, Population and Human Resources Department" (PDF). The World Bank. Retrieved on 2008-05-03. 140. Duesberg PH (1988). "HIV is not the cause of AIDS". Science 241 (4865): 514, 517. doi:10.1126/science.3399880. PMID 3399880. 141. Papadopulos-Eleopulos E, Turner VF, Papadimitriou J, et al (2004). "A critique of the Montagnier evidence for the HIV/AIDS hypothesis". Med Hypotheses 63 (4): 597– 601. doi:10.1016/j.mehy.2004.03.025. PMID 15325002. 142. For evidence of the scientific consensus that HIV is the cause of AIDS, see (for example): o , (2000). "The Durban Declaration". Nature 406 (6791): 15–6. doi:10.1038/35017662. PMID 10894520. Retrieved on 2008-05-03. o Cohen J (1994). "The Duesberg Phenomenon: A Berkeley virologist and his supporters continue to argue that HIV is not the cause of AIDS. A 3-month investigation by Science evaluates their claims." (PDF). Science 266 (5191): 1642–1649. o Focus on the HIV-AIDS Connection: Resource links. National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases. Retrieved on 2006-09-07. o O'Brien SJ, Goedert JJ (1996). "HIV causes AIDS: Koch's postulates fulfilled". Curr. Opin. Immunol. 8 (5): 613–8. PMID 8902385. o Galéa P, Chermann JC (1998). "HIV as the cause of AIDS and associated diseases". Genetica 104 (2): 133–42. PMID 10220906. 143. Smith TC, Novella SP (2007). "HIV denial in the Internet era". PLoS Med. 4 (8): e256. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.0040256. PMID 17713982. 144. Watson J (2006). "Scientists, activists sue South Africa's AIDS 'denialists'". Nat. Med. 12 (1): 6. doi:10.1038/nm0106-6a. PMID 16397537. 145. Baleta A (2003). "S Africa's AIDS activists accuse government of murder". Lancet 361 (9363): 1105. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(03)12909-1. PMID 12672319. 146. Cohen J (2000). "South Africa's new enemy". Science 288 (5474): 2168–70. doi:10.1126/science.288.5474.2168. PMID 10896606. Further reading 2007 AIDS epidemic update (pdf). UNAIDS. Retrieved on 2008-03-21. UNAIDS Annual Report - Making the money work (pdf). UNAIDS. Retrieved on 200803-21. Financial Resources Required to Achieve, Universal Access to HIV Prevention, Treatment Care and Support (pdf). UNAIDS. Retrieved on 2008-03-21. Practical Guidelines for Intensifying HIV Prevention (pdf). UNAIDS. Retrieved on 200803-21.