* Your assessment is very important for improving the workof artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download Approach to chronic cough in children

Survey

Document related concepts

Gastroenteritis wikipedia , lookup

Oesophagostomum wikipedia , lookup

Sexually transmitted infection wikipedia , lookup

Traveler's diarrhea wikipedia , lookup

Neonatal infection wikipedia , lookup

Dirofilaria immitis wikipedia , lookup

Leptospirosis wikipedia , lookup

Hospital-acquired infection wikipedia , lookup

Tuberculosis wikipedia , lookup

Neisseria meningitidis wikipedia , lookup

African trypanosomiasis wikipedia , lookup

Hepatitis C wikipedia , lookup

Hepatitis B wikipedia , lookup

Schistosomiasis wikipedia , lookup

Chagas disease wikipedia , lookup

Middle East respiratory syndrome wikipedia , lookup

Transcript

Approach to chronic cough in

children

د هالة الرفاعي

• INTRODUCTION

• Coughing is an important defensive reflex that

protects from aspiration of foreign

• materials, and enhances clearance of

secretions and particulates from the airways.

Healthy children may

• cough on a daily basis; one study documented

an average of 11 cough episodes every 24

hours

• However, a cough may also be the presenting

symptom of a serious underlying pulmonary or

• extrapulmonary disease. The causes of chronic

cough in children are quite different from that of

adults,

• so evaluation and management of children

should not be based on adult protocols.

Adolescents 15 years

• and older may be evaluated using guidelines for

adults

• The differential diagnosis of chronic cough in

children includes subacute and chronic

infections

• bacterial bronchitis

• pertussis,

• mycoplasma, tuberculosis

• foreign body aspiration, and cough dominant

• asthma

• Gastroesophageal reflux, upper airway cough

syndrome (formerly

• known as postnasal drip syndrome), and

sinusitis are sometimes implicated because of

associations with

• chronic cough in adults, but their role in

causing chronic cough in children is

controversial [

• Less

• common disorders must be excluded if the

cough is unusually severe and/or frequent, or

when there is

• evidence of failure to thrive, growth

retardation, purulent sputum, exertional

dyspnea, hypoxemia, chest

• pain, or hemoptysis

• chronic cough appears to be common, with an

estimated prevalence of 5 to 7

• percent in preschoolers, and 12 to 15 percent in

older children

• Cough is more common among

• boys than girls up to 11 years of age

• and may be less common in developing countries

than in

• affluent countries [

DEFINITION

• There is no consensus as to the length of time in

the definition of chronic cough in

• children. The American College of Chest

Physicians, Thoracic Society of Australia and New

Zealand,

• and many studies have defined chronic cough as

one that lasts more than four weeks, because

most acute

• respiratory infections in children resolve within

this interva

• In comparison, guidelines from the

• British Thoracic Society define chronic cough

as one that lasts more than eight weeks

• However,

• these guidelines also describe a "prolonged

acute cough" as one that lasts at least three

weeks

PHYSIOLOGY

• Each cough occurs through the stimulation of

a complex reflex arc

• This

• is initiated by the irritation of cough receptors

that exist not only in the epithelium of the

upper and lower

• respiratory tracts, but also in the pericardium,

esophagus, diaphragm, stomach, and external

ear

•

•

•

•

Chemical receptors sensitive to acid, heat

mechanical cough receptors can

be triggered by touch or displacement.

The proximal airways (larynx and trachea) are

more sensitive to

• mechanical stimulation, the distal airways more

sensitive to chemical stimulation. Irritation at the

• bronchiolar and alveolar level does not cause

cough

• Impulses from stimulated cough receptors

traverse afferent branches of the vagus nerve to a

"cough

• center" in the medulla and nucleus tractus

solitarius, which itself is under control by higher

cortical

• centers. The cough center generates an efferent

signal that travels down the vagus, phrenic, and

spinal

• motor nerves to expiratory musculature to

produce the cough

• The mechanical events of a cough can be

divided into three phases

• Inspiratory phase: Inhalation, which generates the

volume necessary for an effective cough.

• Compression phase: Closure of the larynx combined

with contraction of muscles of chest wall,

• diaphragm, and abdominal wall result in a rapid rise in

intrathoracic pressure.

• Expiratory phase: The glottis opens, resulting in high

expiratory airflow and the coughing sound.

• Large airway compression occurs. The high flows

dislodge mucus from the airways and allow

• removal from the tracheobronchial tree.

• The specific pattern of the cough depends on the

site and type of stimulation. Mechanical laryngeal

• stimulation results in immediate expiratory

stimulation (sometimes termed the expiratory

reflex),

• probably to protect the airway from aspiration;

stimulation distal to the larynx causes a more

prominent

• inspiratory phase, presumably to generate the

airflow necessary to remove the stimulus

• Cough is an important defensive reflex that is

required to maintain the health of the

• lungs. Children who do not cough effectively

are at risk for atelectasis, recurrent

pneumonia, and chronic

• airways disease from aspiration and retention

of secretions

• Many disorders can impair a child's ability to

• cough effectively, resulting in persistent

cough. Children with neuromuscular disease

and chest wall

• deformities may not generate a deep enough

inspiratory volume or expiratory flow

necessary for

• effective clearance of secretions due to

defective "pump" mechanisms

• Children with reduced

• function of the abdominal wall musculature are particularly

at risk for ineffective cough. Children with

• tracheobronchomalacia

• ("floppy" airways), or with obstructive airways diseases,

often do not generate

• the high flow rates needed for effective clearance of

secretions. Individuals with laryngeal disorders,

• including those with tracheostomies, may not achieve

sufficient laryngeal closure to generate the

• increased intrathoracic pressures necessary for an effective

cough [

DIAGNOSTIC APPROACH

• Children with chronic cough should be

evaluated with a detailed history, physical

examination, chest

• radiograph, and (if the child is able)

spirometry

• This evaluation often provides sufficient

• information to categorize the cough as specific

(ie, caused by an underlying disease) or

nonspecific

• Specific cough — The causes of specific

chronic cough fall into the following general

categories

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

Asthma

Persistent bacterial bronchitis

Chronic suppurative lung disease and bronchiectasis

Airway abnormality (congenital, foreign body, or

neoplastic)

Aspiration

Chronic or less common infections

Interstitial lung disease

Extrapulmonary causes: cardiac abnormalities, ear

conditions

• The sequence of evaluation for these

disorders is informed by the age and

presenting features of the

• child. Identification of the presenting features

and cough characteristics is important

because many are

• easily recognizable and strongly suggestive of

a specific cause; this is less true in adults.

• Key symptoms and signs — Certain symptoms

and signs are highly predictive of a specific

cough.

• These signs or symptoms narrow the

diagnostic possibilities and call for further

specific testing or

• referral

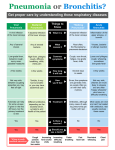

• Chronic wet cough

• Wheezing or crepitations

• Onset after an episode of choking, or sudden

onset while eating or playing

• Abnormal chest radiography or spirometry

• Associated cardiac or neurologic abnormalities

• Failure to thrive, feeding difficulties, or

hemoptysis

• the symptom of a chronic wet cough, with or

without production of purulent sputum, is

• always pathologic and warrants investigations

for a persistent endobronchial infection

(persistent

• bacterial bronchitis or chronic suppurative

lung disease), retained airway foreign body, or

• immunodeficiency

• Nonspecific cough — If symptoms suggesting

specific cough are absent and the chest

radiograph and

• spirometry are normal

• the possibility of asthma should be considered

and pursued with an empiric

• trial of bronchodilators and other asthma

medications

• If there is no response, the child should be

considered to have a nonspecific cough, and

the medication

• should be stopped. The child and parents

should be reassured and the patient observed

over time for

• possible emergence of specific symptoms

• HISTORY — The diagnostic approach outlined

above requires a detailed history, which should

focus on

• the following key elements

• Age and circumstances at onset — Neonatal

onset of coughing should prompt consideration

of

• congenital malformations (eg,

tracheobronchomalacia), conditions predisposing

to aspiration

• tracheoesophageal fistula, laryngeal cleft, or a

neurological disorder), or chronic pulmonary

infections

• (eg, cystic fibrosis or ciliary dyskinesia

• A cough that begins suddenly while playing or eating,

especially in the toddler age range, should raise

• suspicion of an aspirated foreign body in the airway.

The physician should specifically ask about a

• history of choking, because this may have occurred

weeks before and the family may not voluntarily

• recall the information. Even if there is no history of

choking, a foreign body remains a diagnostic

• possibility

• An episode of severe pneumonia can damage

the airways, making the child vulnerable to

chronic cough.

• More rarely, severe pneumonia may cause

frank bronchiectasis. A psychogenic or

habitual cough also

• often begins after an upper respiratory

infection.

Nature of the cough

• .

• Chronic paroxysmal cough triggered by

exercise, cold air, sleep, or allergens is

• often seen in patients with asthma.

• Barking or brassy cough suggests a process in

the trachea or more

• proximal airways, such as airway malacia,

laryngotracheobronchitis, spasmodic croup, or

foreign body

• Staccato cough in young infants can be the

result of infection with Chlamydia

trachomatis. Cough that is

• honking ("Canadian Gooselike")

• and disappears at night suggests a

psychogenic or habitual cough.

• A chronic productiv coughe

• suggests a suppurative process, and may require

further

• investigation to exclude

• Bronchiectasis

• cystic fibrosis immune deficiency, or congenital

• malformation

• active infection

• Acute or subacute paroxysmal cough suggests

infection with pertussis or parapertussis; this

characteristic

• cough can be retriggered by subsequent upper

respiratory illness

Timing and triggers

• The timing and triggers associated with cough

can help guide diagnosis

• Cough

• due to asthma typically occurs following

exposure to characteristic asthma triggers (ie,

allergens, smoke,

• exercise, cold air, or viral infection), and

typically worsens during sleep

• Cough associated with nasal

• problems typically is worst during changes of

position,

• while cough due to bronchiectasis typically is

• worst and most productive early in the day.

• Cough that is triggered during swallowing is

suggestive of aspiration, either primary or due

totracheoesophageal fistula or laryngeal

abnormalities

• Cough in the first hour after meals, or which is

• worse while supine, may reflect

gastroesophageal reflux

Associated symptoms

• A history of dyspnea or hemoptysis should trigger

a search for an underlying

• lung disease

• Hemoptysis should also raise concerns of

bronchiectasis, cavitary lung disease (tuberculosis

• or bacterial abscesses), heart failure,

hemosiderosis, neoplasm, foreign bodies,

vascular lesions, endobronchial lesions,

catamenial bleeding, and clotting disorders

• Cough, with or without symptoms of

pancreatic insufficiency, recurrent

endobronchial infection, and/or

• failure to thrive should raise suspicion of cystic

fibrosis

• Cough associated with persistent fever, and/or

• failure to thrive, or weight loss should raise

suspicion of chronic infection and immune

deficiency

• Children with neurologic impairment or

seizures frequently have chronic aspiration

• Anaphylactic reactions to food can include

cough but are unlikely to present with

recurrent cough in the

• absence of other symptoms of anaphylaxis

Past medical history

• The past medical history should include an

account of the pregnancy, labor, and

• delivery, as well as the neonatal course

• Low birth weight and/or premature neonates

are at risk for

• developing atopic sensitization and asthma.

• The past medical history should also include

questions related to eczema and pulmonary

infections. In

• preschool children, a history of infantile

eczema is often associated with inhalant

allergy

Family history

• Family history of atopy or asthma increases

the risk in offspring, and suggests a

• diagnosis of either allergic rhinitis or asthma

in the child with chronic cough

• Family history of

• cystic fibrosis or primary ciliary dyskinesia should raise

suspicion for these disorders.

• A careful history

• should be obtained for current illness in family

members or close contacts; such individuals with

cough,

• weight loss, and night sweats should arouse suspicion

of tuberculosis. In some cases, the possibility of

• HIV transmission from mother to child should be

assessed

• Social history and environmental exposures

• Passive or active exposure to smoke from tobacco

• marijuana, cocaine or other chemical irritants can

result in chronic cough

• In addition, woodburning

• stoves cause indoor air

• pollution and can predispose children to

respiratory infection s Gas stoves are also

associated with

• respiratory symptoms in children

• It is important to elicit any history of contact with

pets or other animals, as cough may be induced

by

• allergy to the animals. Similarly, the location of

the child's home and travel history may be

relevant.

• Local epidemiology can inform the diagnostic

considerations, especially with respect to

endemic fungal

• and parasitic infections

• Histoplasmosis is commonly associated with

exposure to birds and

• bats, and echinococcosis with exposure to

dogs and sheep

• Medications — Response to prior therapy may

yield some diagnostic clues regarding the

cause of

• chronic cough. Previous response to

antihistamines suggests a component of

rhinitis and postnasal drip,

• while a response to inhaled bronchodilators

suggests possible asthma.

• Any medications taken by the patient should

be reviewed carefully; angiotensin converting

enzyme

• (ACE) inhibitors are a wellestablished

• cause of chronic cough. Patients previously

treated with cytotoxic

• drugs or thoracic radiation are at risk of

interstitial lung disease.

PHYSICAL EXAMINATION

• General examination — The physical

examination should pay close attention to the

following signs of

• chronic underlying disease

• General appearance of chronic illness

• Poor growth, thinness, or obesity

• Increased work of breathing, retractions, accessory

muscle use, chest wall hyperinflation or

• deformity, abnormal breath sounds (reduced intensity,

asymmetry, wheezing, stridor, crackles)

• Shiners, swollen nasal turbinates, nasal obstruction,

nasal polyps, allergic nasal crease, halitosis,

• tonsillar hypertrophy, pharyngeal cobblestoning, high

arched or cleft palate, hoarseness

•

•

•

•

Tympanic membrane scarring or frank otorrhea

Abnormal heart sounds, abnormal pulses

Hepatoand/

or splenomegaly, abdominal masses, bloating,

rectal prolapse

• Edema of the extremities, cyanosis and/or

clubbing of the digits

• Rashes and other skin lesions (eg, scars of healed

recurrent impetigo)

Chest examination

• Polyphonic wheezing (ie, many different

pitches) with cough is typical of asthma; the

wheezing occurs

• on expiration and sometimes also on

inspiration

• Many children with asthma are also atopic

and exhibit

• signs of rhinitis, conjunctivitis, and/or eczema

• Other causes of polyphonic wheezing include

viral

• bronchiolitis, obliterative bronchiolitis,

bronchiectasis (cystic fibrosis, allergic

bronchopulmonary

• aspergillosis, primary ciliary dyskinesia),

bronchopulmonary dysplasia, heart failure,

immunodeficiency, bronchomalacia, and

aspiration syndromes.

Monophonic wheezing

• Monophonic wheezing (a single, distinct noise

of one pitch and starting and stopping at one

discrete

• time) and cough should always raise suspicion

of large airway obstruction caused by foreign

body

• aspiration or malacia and/or stenosis of the

central airways

• lymphadenopathy, and mediastinal

• tumors can cause extrinsic large airway

obstruction. Tuberculosis should always be

considered in a child

• with a monophonic wheeze, particularly in

areas where the disease is prevalent

CHEST RADIOGRAPHY

• In addition to a thorough history and physical

examination, a chest

• radiograph should be obtained. If foreign body

aspiration is suspected because of the age, clinical

• presentation or history, frontal films should be

obtained during both inspiration and expiration, to

• evaluate for unilateral lung hyperinflation that would

suggest airway obstruction. Similar information can

• be obtained from the combination of frontal, right

lateral decubitus, and left lateral decubitus

• radiograph

PULMONARY FUNCTION TESTS

• Spirometry will show signs of obstruction in

diseases that

• obstruct the airways, and restriction in

interstitial or chest wall restrictive processes.

Suboptimal effort on

• the part of the child will also result in a

restrictive picture; thus, spirometry should be

conducted by a

• technician proficient in testing children

• If an obstructive pattern is seen on the expiratory

flowvolume

• loop, the reversibility of the obstruction

• can be assessed by measuring FEV1 before and

after inhalation of a bronchodilating agent. A

positive

• response to bronchodilators establishes the

presence of airway reactivity, and is suggestive of

asthma but

• does not rule out other disorders

BRONCHOSCOPY

• The primary indication for urgent

bronchoscopy in children with chronic cough

• is for suspected foreign body aspiration.

• Bronchoscopy is also valuable in the

evaluation of suspected airway malacia,

tracheoesophageal fistula,

• or stenosis

• Patients with presumed infectious etiologies in

whom a sputum sample is not obtained or

• yields negative results can be evaluated with

flexible bronchoscopy to perform

bronchoalveolar lavage

• for bacterial, fungal, and mycobacterial cultures.

Bronchial brushings can also be taken for patients

with

• suspected ciliary dyskinesia, although nasal

brushings also may be used

OTHER TESTS

• Esophageal pH monitoring —

• Whether gastroesophageal reflux disease

(GERD) is an important cause

• of isolated chronic cough in children is

controversial. Most authorities suggest that

this is not a common

• Sinus imaging

• Tuberculin testing

• Allergy testing

SUMMARY AND RECOMMENDATIONS

• There is no consensus definition of the time frame for

chronic cough in children. Chronic cough is

• often defined as a cough lasting more than four weeks,

because most acute respiratory infections in

• children resolve within this interval. Other schemes

define chronic cough as one that last more than

• eight weeks but also recognize that a relentlessly

progressive cough often warrants evaluation prior

• to eight weeks

• Chronic cough can be a symptom of congenital

anomalies, genetic disease, airway

obstruction,

• infection, airway inflammation without

infection (as in asthma), neoplasia, or

psychogenic

• processes

• The evaluation of a child with chronic cough

should include a detailed history, physical

• examination, chest radiograph, and

spirometry (when possible

• Symptoms and signs that are highly predictive of

a specific cough include chronic wet cough,

• wheezing or crepitations, onset after a choking

episode, abnormal chest radiography or

spirometry,

• associated cardiac or neurologic abnormalities,

and failure to thrive, feeding difficulties, or

• hemoptysis. These signs or symptoms narrow the

diagnostic possibilities and call for further

• specific testing or referral

• The symptom of a chronic wet cough in a

young child, usually indicates persistent

bacterial

• sinusitis or retained foreign body

شكرا •