* Your assessment is very important for improving the workof artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download European Retail Forum - the European Environmental Bureau

Product placement wikipedia , lookup

Marketing mix modeling wikipedia , lookup

Multicultural marketing wikipedia , lookup

Food marketing wikipedia , lookup

Multi-level marketing wikipedia , lookup

Marketing communications wikipedia , lookup

Street marketing wikipedia , lookup

Online shopping wikipedia , lookup

Direct marketing wikipedia , lookup

Visual merchandising wikipedia , lookup

Planned obsolescence wikipedia , lookup

Integrated marketing communications wikipedia , lookup

Marketing strategy wikipedia , lookup

Youth marketing wikipedia , lookup

Global marketing wikipedia , lookup

Consumer behaviour wikipedia , lookup

Advertising campaign wikipedia , lookup

Neuromarketing wikipedia , lookup

Supermarket wikipedia , lookup

Product planning wikipedia , lookup

Sensory branding wikipedia , lookup

European Retail Forum

Issue sheet # 3

Marketing and effective

communication

In a globalised economy, average consumption levels are on the rise due to:

increasing world population;

the expansion of middle and lower-income consumers and of a general culture of consumerism

economic systems in industrialised societies based on consumption and production

These levels of consumption are unsustainable, and the improvements in energy efficiency and the emergence

of new technologies do not outweigh them (called the ‘rebound effect’), resulting in increased environmental

damage. Changes in lifestyles are therefore necessary. For consumers this entails considering whether

material consumption is necessary and modifying the ways in which they choose and use products and

services. Given that the public behaves within the societal structure in which it lives, there is also a need for

economic models, public policy and business behaviour and models to reflect sustainable consumption and

production as a central objective.

Introduction

Advertising1, communications2 and marketing3 aim to encourage the purchase of goods or services, in other

words to encourage consumption. They are used to create customer demand, satisfy customer requirements

and retain customer loyalty. Product communication to the consumer is mainly part of the promotion

instrument. The effectiveness of marketing instruments is usually measured in increased sales. Improvements

in customer satisfaction or customer loyalty could also be objectives of marketing instruments even if it is hard

to measure direct impact.

Within the context of sustainable consumption and production (SCP), future use of these sales tools will need

to refined, to help in addressing the issue of the ‘rebound effect’ and to make consumption patterns more

sustainable. For instance, they can be used to communicate more sustainable lifestyle messages, rather than

simply aiming to increase sales of better performing (environmentally and socially) products. This requires

coherence between a companies CSR or sustainability objectives and its marketing objectives and practices.

However, retailers and producers alone cannot achieve such a shift – public policy frameworks and more

sustainable economic models are needed, to ensure a harmonised approach and the right framework

conditions for SCP.

As a start, corporate and product advertising, communications and marketing have a role to play alongside

According to Wikipedia, advertising is a form of communication intended to persuade its viewers, readers or listeners to take some

action. It usually includes the name of a product or service and how that product or service could benefit the consumer, to persuade

potential customers to purchase or to consume that particular brand. Modern advertising developed with the rise of mass production in

the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Commercial advertisers often seek to generate increased consumption of their products or

services through branding, which involves the repetition of an image or product name in an effort to associate related qualities with the

brand in the minds of consumers.

1

According to Wikipedia, corporate communication is the communication issued by a corporate/organization/body/institute to all its

public(s). Publics can be both internal (employees, stakeholders, i.e. share and stock holders) and external (agencies, channel partners,

media, government, industry bodies and institutes, educational institutes and general public). The Corporate Communication area will

help this organization to build its message, combining its vision, mission and values and will also support the organization by

communicating its message, activities and practices to all of its stakeholders. Organizations can strategically communicate to their

audiences through public relations and advertising.

2

According to Wikipedia, marketing is the process by which companies advertise products or services to potential customers. It is an

integrated process through which companies create value for customers and build strong customer relationships in order to capture

value from customers in return. Marketing is used to create the customer, to keep the customer and to satisfy the customer. The

evolution of marketing was caused due to mature markets and overcapacities in the last decades. Companies then shifted the focus from

production to the customer in order to stay profitable. The term marketing concept holds that achieving organizational goals depends on

knowing the needs and wants of target markets and delivering the desired satisfactions. It proposes that in order to satisfy its

organizational objectives, an organization should anticipate the needs and wants of consumers and satisfy these more effectively than

competitors.

3

1

consumer information and education in general, in changing consumer consumption patterns. These enable

consumers to question whether material consumption is necessary, and when it is, to find, choose and use

environmentally friendlier products and services, by providing information, ensuring availability and

affordability.

Sales tools can also have a role in leveraging the company’s sustainability credentials to build brand equity. In

order to do this, it is vital to ensure consistency with the respective corporate sustainability strategy; any

claims made must be presented in a specific, accurate and unambiguous manner.

Scope

The subject of marketing and effective communication in the context of SCP is not easily addressed, given that

the financial success of a retail company is based on its sales. At the heart of the debate is how to develop a

public that is informed of sustainability issues to be able to behave sustainably, beyond their purchasing

decisions – that is, in their use and end-of-life management decisions of the products they purchase. The

starting point is to make it much easier to behave sustainably than unsustainably, including without making

conscious decisions to make sustainable choices.

Retailers are well-placed to help add to solutions as they form a bridge between the supply base and customers,

with the potential to influence a very large number of people. “Retail is almost unique in its ability to reach out to

a very large number of people in their everyday lives to push the sustainability agenda and raise awareness of

the issues.”5

Since retailers alone cannot create a sustainably behaving public, the focus of this issue paper is in what

retailers can do now, before looking at what more is needed for retailers to be able to do more. Helping people

to behave more sustainably means making better performing products more easily available and attractive to

the public, and communicating messages of sustainable behaviour. Coherence between CSR/sustainability

objectives and the communications strategy/activities/messages of retailers is central to this, as is the

availability and easier accessibility of these better performing products.

Marketing instruments to promote green buying

For the marketing of better performing products, companies use marketing instruments which are well

established for other products. The key challenge is to build trust that such products produce real advantages

for the environment and perform equally well as the product formerly used.

In the competitive world between different brands, named brands and own brands and between numerous

retailers, consumers decide on the success of different marketing instruments through their daily purchasing

decisions.

Customer-focused marketing is based on the four Ps: product, promotion, price and placement. For fast

moving consumer goods (FMCG)6, a consumer will stay in a store up to 45 minutes but will decide, on average,

within 5 seconds which of a different product type to choose from the shelf. Furthermore, studies show that a

typical consumer can take in a maximum of 7 messages for each product, including the name of the product.

The most important determinants in the consumer’s decision to purchase or not to purchase a particular

product are the price and performance/quality of products. The marketing ‘mix’ used by the retailer, is

therefore very important in helping to shape the sustainable consumer before they enter the store and after

they have left it.

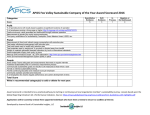

Assessing the effectiveness of marketing and consumer information

Methods for assessing the effectiveness of marketing and communication tools differ depending on the actor

(producer, retailer, environmental or consumer NGO etc.) and the initiative. For retailers and producers the

success of a marketing initiative will usually be assessed on the basis of increased sales, numbers of people

visiting the store etc. Sales data and market research allow for a better understanding of consumer attitudes,

beliefs and behaviours that can then be fed into the planning process, driving innovation and guiding key

business decisions, including pricing, packaging and distribution. Nevertheless, from a sustainability

« Stern – Initial comments from the Retail Sector », Retail Sector Working Group, 2007. The response from the retail sector to the

Stern Report on the economics of climate change.

6

Frequently purchased at relatively low cost of essential or non essential goods such as food, toiletries

REFERENCE MISSING HERE

5

2

perspective the real challenge is to ensure that the consumer will develop loyalty to better performing products

(purchasing these instead of poorer performing ones), and changing their habits when using and finally

disposing of the product. For instance, reverting to compact washing powder requires using less product.

The EU Legal Framework

At European level, the renewed sustainable development strategy adopted by the European Council in 2006

called for an action plan on Sustainable Consumption and Production. The SCP and SIP (sustainable industrial

policy) action plan was adopted in June 20088. The Action Plan is the EU’s contribution to a global (UNEP)

process on sustainable consumption and production, building upon both the Rio and the Johannesburg

Summits. The Johannesburg Plan of Implementation includes the following as measures to be taken as part of

plans and programmes on SCP:

Develop production and consumption policies to improve the products and services provided, while

reducing environmental and health impacts, using, where appropriate, science-based approaches, such

as life-cycle analysis;

Develop awareness-raising programmes on the importance of sustainable production and consumption

patterns … through … education, public and consumer information, advertising and other media…;

Develop and adopt, where appropriate, on a voluntary basis, effective, transparent, verifiable, nonmisleading and non-discriminatory consumer information tools to provide information relating to

sustainable consumption and production, including human health and safety aspects

The EU’s action plan sets out measures aimed at improving the environmental performance of products and

fostering their uptake by consumers and public authorities. It contains other concrete proposals: on the

production side:

extension of the Eco-design directive to cover all energy related products. Minimum requirements are

set for products with significant environmental impact, focusing on key environmental aspects

revision of the EMAS Regulation

On the consumption side:

extension of the energy labelling directive to include more products;

revision of the eco-label Regulation;

the setting up of the Retail Forum;

communication on green public procurement.

However, there is currently no public policy framework on ecodesign (beyond energy-related products), to help

to send clear signals to manufacturers on the need to make improvements to their products, nor are there

harmonised, agreed tools on how to identify the key environmental or sustainability impacts of products or

how to choose between impacts when deciding improvement measures (for example between water

consumption and chemical substances). There is also not a clear consensus, based on sound scientific,

measurable and transparent criteria, of what is meant by “sustainable” “green”, “ecological”, “environmentally

friendly”, “environmentally friendlier” etc. products.

Despite these fundamental policy gaps, retailers need to move forward on making better performing products

available on the market. Better performing products, we propose, include all products which go beyond

minimum legal requirements from an environmental perspective. It therefore includes products such as ecolabelled products and other certified schemes, but also those which are not subject to third party verification.

The EU’s SCP action plan did not propose the development of sustainable consumption policy. This is needed if

we are to address this important issue, beyond the current Action Plan approach of labelling and consumer

information.

There is also currently no specific EU legislation regulating environmental communication and marketing. There is

however a general directive on unfair commercial practices, which covers misleading commercial practices and

applies therefore to misleading environmental claims (see Art. 6 of Directive 2005/29/EC). This Directive ensures

that consumers are not misled and that any claim made by traders in the EU is clear, truthful, accurate and

substantiated, thus enabling consumers to make informed and meaningful choices. Furthermore, the Directive

aims to ensure, promote and protect fair competition in the area of commercial practices. In order to develop a

common understanding and a convergence of practices when implementing and applying the Directive, the

Commission has recently published a document ("Guidance on the implementation/application of directive

8

(COM (2008) 397 final)

3

2005/29/EC on unfair commercial practices") on the key concepts and provisions of the Directive, perceived to

be problematic. A chapter of this document is devoted to misleading environmental claims. 9

Opportunities and Barriers

The EU’s SCP action plan does not include a vision on where we need to go, nor clear objectives to help us

achieve that vision. Such a public policy framework is needed to help retailers, manufacturers, governments

and civil society organisations to work together towards a common goal.

A major challenge towards sustainable consumption patterns is to foster in consumers long-term

environmental values which they integrate into purchasing behaviour and decisions. Such values changes are

better supported by coherent messages from ‘education’ tools such as awareness-raising, formal education,

advertising, media, etc. For such education to be effective, however, identical or similar messages must be

given by a number of different sources.

Due to their strategic position in the supply chain, retailers are important conveyers of such messages. They

also have a long experience in working with other players along the supply chain, such as manufacturers,

NGOs, media, public authorities etc. These messages have maximum effect if they are clear, simple and, when

possible, highlight the financial advantage for the consumer.

The current EU2020 (Lisbon Strategy post-2010) offers the opportunity for the Retail Forum to communicate

on the need for economic policy to include measures on truer pricing, such as VAT reduction on better

performing products. Support for economic policy that is coherent with sustainability needs to be made public.

Opportunities

Consumers are increasingly aware of environmental issues - in particular, climate change - and are more and

more receptive to environmental messages. For instance, according to the Eurobarometer survey on

Europeans’ attitudes towards SCP, the level of environmental awareness of the impact of consumer products is

high: some 55% say they fully know or know the most significant impacts of the products they buy.

Consequently, there is an opportunity to develop national messages on sustainability issues, to which retailers

can contribute and participate.

Environmental sustainability has already become a competitive tool for retailers, particularly due to public

interest in climate change. Individual retailers are already competing on climate change activities, and on

other sustainability issues. The opportunities for better coherence between sustainability objectives and

marketing objectives and messages is therefore much easier than in the past.

To demonstrate their commitment and increase their credibility, many large retailers have already set up

partnerships and/or are running campaigns with environmental or consumer NGOs, manufacturers and public

authorities (environment ministries, environmental agencies) etc. Partnerships with NGOs may take different

forms. Most frequently, NGOs provide assistance in the development of the environmental sustainability

strategy of the company, the communication of environmental information and the identification of

environmentally friendlier products.

Retailers may also decide to promote voluntary initiatives from manufacturers (such as the wash right

campaign), or other schemes such as the EU eco-label as part of their product selection activities. The easier

availability of better performing products on shop shelves can be improved through increased efforts by buyers

to identify the better performing products across a wider range of product groups.

On the wider public policy framework, 2012 is a key year when reviews of SCP Action Plan and the Ecodesign

of Energy-Related Products Directive will take place. These will be a prime opportunity to develop an Action

Plan with more details, clearer objectives, and more support mechanisms including ‘education’ elements

involving collaborative activities in which retailers could participate more systematically.

9

Beyond the "black list" contained under Annex I of the Directive, where some practices are always considered unfair, and therefore

prohibited, regardless of the impact they have on the consumer's behaviour, the above mentioned Guidelines highlight two different

situations, regarding environmental claims, which may occur:

(i)

Objective misleading practice: the environmental claim is misleading because it contains false information and is therefore

untruthful.

(ii)

Subjective misleading practice: the environmental claim is misleading because it deceives or is likely to deceive the average

consumer, even if the information contained therein is factually correct.

Breaches of binding codes of conduct containing environmental commitments may also be considered misleading actions

4

Barriers

Gaps in key public policy areas, including in SCP and products mean the wider societal framework does not

exist to help guide retailers, manufacturers, or the public towards sustainable behaviour. Where tools do exist

– Energy-related Products Directive, Ecolabel – these cover a very narrow range of products and on their own

cannot build the ‘critical mass’ of sustainable behaviour. Additionally, recent political decisions on consumer

successes such as the Energy Label now no longer communicate clear messages about the performance of the

products in relation to the A-G range.

Many studies on consumer behaviour demonstrate the wide gap between what consumers say and what they

do. Understanding and overcoming this barrier should be a priority, using research that already exists10. When

asked, consumers often identify the following barriers to environmentally friendly consumption habits:

lack of understanding how they, as consumers, can make a difference;

lack of information about what they can do;

that purchasing environmentally friendlier products is financially onerous;

doubts about the quality and level of performance of environmentally friendlier products.

These remarks partially stem from the absence of a definition of environmentally friendlier products. Making

better use of the scientific research already available (recognised LCA approaches with sound criteria for each

product category, etc.) could solve some of the confusion.

In the absence of definitions and clear rules of what can be called “environmentally friendlier”, some

environmental claims appear merely to be “green washing” These tend to be picked up by the media and are

therefore potentially damaging to a company’s credentials, and to consumer confidence in general. Only 6 %

of respondents to the EU barometer survey claimed to fully trust producers’ claims.

For this reason, many retail companies, fearing attacks from NGOs, the media or legislators, are reluctant to

promote products which meet standards beyond legal minima, such as the GlobalGan (the BRC consumer

goods standard which covers 100% of non-food products).

Well-designed LCA tools can identify what the key environmental impacts are and where along the lifecycle of

the product they occur, whether in production, use or disposal. Misconceptions about areas of greatest

environmental impact lead to the general conclusion that claims may not always convey the overall picture.

Yet to deliver an effective communication, it is important to convey the whole picture.

Consumers also sometimes expect environmentally friendlier products to cost more than standard products:

they therefore tend to be niche markets. However, prices could be reduced by means of public procurement,

which would allow economies of scale. Consumers also occasionally question the performance of

environmentally friendlier products. These issues become especially relevant in periods of economic

uncertainty. What about economic reform policy? There is a COMM strand of work on this – roadmap on

elimination of environmentally harmful subsidies, ecological fiscal reform (including reduced VAT, bonus-malus

schemes, etc).

The competitive nature of purchasing (individual retailers trying to get the best ‘offer’ on a product) has

prevented retailers from sharing best practice on sustainability issues such as criteria selection for better

performing products. Overcoming the challenges of sustainability (how to encourage manufacturers to make

better performing products, how to identify these, how to reduce environmental impacts, etc) requires

collaborative effort. The tension between sustainability and competition needs to be reduced, with retailers

working together more than in the past, to create a market-wide demand for better performing products. DG

Competition needs to be part of the discussion, to avoid anti-trust arguments coming when these are not

appropriate.

There is also a practical obstacle to the promotion of environmentally friendlier products, namely that the

supply does not always meet the demand, as is the case for organic products. This forces retailers to source

globally (for example organic products from China), jeopardising the environment credentials of the product.

Legal barriers

Lack of public policy and appropriate legislative measures to back-up sustainable consumption, and particularly

Most notably, studies undertaken by Tim Jackson, Professor of Sustainable Development at Surrey University in the UK. For a list of

his relevant work, see: http://www.surrey.ac.uk/resolve/view_profiles.php?teamMember_ID=15

10

5

product policy. No comprehensive legal basis for improving products, beyond the Energy-related Products

Directive, Ecolabel, and Energy Label. General Product Safety Directive does not link safety and sustainability.

The legal dimension can also prove to be an obstacle. In particular, the amount of mandatory on-pack

information required may cause that the key messages are overlooked.

National implementation is not always in line with EU legislation, as in fishing quotas, preventing clear, simple,

homogeneous information as well as an agreement on what is sustainable.

Increasingly, positions taken by Commission officials on antitrust rules may also create barriers as they

prevent collective choice-editing decisions (e.g. energy efficient light bulbs in the UK).

Internal barriers

In smaller retail companies, environmental challenges are often misunderstood or under evaluated.

For larger companies, diverging views can be had between the marketing and sustainability departments as to

what is a “sexy” product or message to put forward. Moreover, retail companies are often structured in such a

way as to leave as much discretion as possible to each shop regarding what they sell and the messages they

convey, limiting the possibilities for large scale marketing and communication. According to a recent study on

retailers and CSR11, progress along change trajectories towards effective CSR requires both ‘internal’ and

‘external’ strategic and operational alignment.

To communicate their general company sustainability strategy, larger retailers use sustainability reports. Yet

generally these are not directly addressed to consumers but to shareholders etc. Communication on this point

needs to be improved to help improve the credibility of the retail brand.

Transfer of Good Practices

Companies to give one, max. 2 examples of successful

Conclusions and possible areas for action

Changing consumer habits and consumption patterns towards more sustainable ones is a long-term objective.

Key challenges

Development of clearer policy on SC and SP – links to innovation

Economic policy that reflects sustainability of products and services – stimulate discussion during EU2020 and

economic recovery exit strategies

sound definition and common understanding of what are better environmentally performing products and

what the key environmental hot spots are for each product family (making better use of available science +

framework to elaborate guidelines);

identifying what messages should be conveyed, in order to support consumers making informed choices

and to promote behavioural change;

closing the gap between what consumers say and what they do;

make environmentally friendlier products affordable;

convincing consumers to buy an environmentally friendlier product a second time with a view to a final

change in consumer behaviour;

reconciling product information and broader messages (sustainable life-style etc.), without ignoring the

fact that information overload negates the benefit of the information.

What retailers can do

facilitate access to environmentally friendlier products (choice editing) at affordable prices;

“CSR business models and change trajectories in the retail industry: A Dynamic Benchmark Exercise (1995-2007); LEI Wageningen

UR, The Hague; October 2009

11

6

all environmental claims should be clear, credible and comparable. “Green washing” should be avoided by

relying on verifiable, transparent information and easy-to-understand labels;

relaying sustainable consumption messages through participation in government and civil society

campaigns (e.g. sustainable energy Europe week, mobility week, world environment day…);

communicate the company’s vision on sustainability and ensure that the stores concerned meet the

respective messages communicated and are consistent at all stages.

What policy-makers can do

improve the knowledge base, identifying the hot spots according to consistent and credible LCAs. Current

environmental LCA databases are often incomplete (missing emission factors for many common ingredients

and components). Harmonisation between these databases is needed to make them interoperable.

Intensify efforts for better consumer education by public authorities and other players consumers trust.

Messages must also be consistent over time.

facilitate access to environmentally friendlier products (choice editing) at affordable prices; - bonus/malus,

VAT reduction, shift from labour to resources

Revise mandatory rules on packaging information. Other instruments like additional information by SMS or

on websites probably appropriate.

Stimulate and promote the ecolabel and organic schemes to increase the number of products with such

labels. Enhance knowledge and credibility of these schemes.

What retailers and other stakeholders can do

collaborate further with all the relevant stakeholders along the supply chain, including public authorities,

to share best practices regarding the promotion of environmentally friendlier products and to develop simple

common messages on issues to be identified and/or build on existing initiatives.

conduct marketing and communication assessments to focus more on sustainability criteria, including

comparison between the effectiveness of different communication tools;

conduct campaigns linking consumption and lifestyle. For some products the major environmental impacts

are related to the way the products are used and dealt with as waste; some types of products promote more

sustainable lifestyles than others. Involve all relevant parties in such campaigns to make a sustainable lifestyle

trendy.

build-on existing best practices, partnerships, campaigns and voluntary actions carried out by relevant

stakeholders

7