* Your assessment is very important for improving the work of artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download Part IV: Stars

Corona Australis wikipedia , lookup

Rare Earth hypothesis wikipedia , lookup

Canis Minor wikipedia , lookup

Auriga (constellation) wikipedia , lookup

Dialogue Concerning the Two Chief World Systems wikipedia , lookup

Tropical year wikipedia , lookup

Corona Borealis wikipedia , lookup

Astronomical unit wikipedia , lookup

International Ultraviolet Explorer wikipedia , lookup

Dyson sphere wikipedia , lookup

Observational astronomy wikipedia , lookup

Cassiopeia (constellation) wikipedia , lookup

History of Solar System formation and evolution hypotheses wikipedia , lookup

Cygnus (constellation) wikipedia , lookup

Solar System wikipedia , lookup

Canis Major wikipedia , lookup

Formation and evolution of the Solar System wikipedia , lookup

Perseus (constellation) wikipedia , lookup

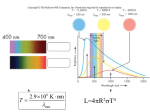

Stellar classification wikipedia , lookup

H II region wikipedia , lookup

Planetary habitability wikipedia , lookup

Aquarius (constellation) wikipedia , lookup

Astronomical spectroscopy wikipedia , lookup

Future of an expanding universe wikipedia , lookup

Stellar kinematics wikipedia , lookup

Corvus (constellation) wikipedia , lookup

Timeline of astronomy wikipedia , lookup

Standard solar model wikipedia , lookup