* Your assessment is very important for improving the work of artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download Amino Acids

Discovery and development of integrase inhibitors wikipedia , lookup

Discovery and development of proton pump inhibitors wikipedia , lookup

Discovery and development of direct Xa inhibitors wikipedia , lookup

Ribosomally synthesized and post-translationally modified peptides wikipedia , lookup

Metalloprotein wikipedia , lookup

Discovery and development of ACE inhibitors wikipedia , lookup

168397_P001-012.qxd7.0:02 Protein structure 5-20-04

2010.4.4

9:45 AM

Page 1

UNIT I:

Protein Structure

and Function

1

Amino Acids

I. OVERVIEW

Proteins are the most abundant and functionally diverse molecules in

living systems. Virtually every life process depends on this class of

molecules. For example, enzymes and polypeptide hormones direct and

regulate metabolism in the body, whereas contractile proteins in muscle

permit movement. In bone, the protein collagen forms a framework for

the deposition of calcium phosphate crystals, acting like the steel

cables in reinforced concrete. In the bloodstream, proteins, such as

hemoglobin and plasma albumin, shuttle molecules essential to life,

whereas immunoglobulins fight infectious bacteria and viruses. In short,

proteins display an incredible diversity of functions, yet all share the

common structural feature of being linear polymers of amino acids. This

chapter describes the properties of amino acids. Chapter 2 explores

how these simple building blocks are joined to form proteins that have

unique three-dimensional structures, making them capable of performing specific biologic functions.

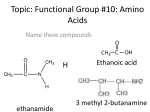

II. STRUCTURE OF THE AMINO ACIDS

Although more than 300 different amino acids have been described in

nature, only 20 are commonly found as constituents of mammalian proteins. [Note: These are the only amino acids that are coded for by DNA,

the genetic material in the cell (see p. 395).] Each amino acid (except

for proline, which has a secondary amino group) has a carboxyl group,

a primary amino group, and a distinctive side chain (“R-group”) bonded

to the α-carbon atom (Figure 1.1A). At physiologic pH (approximately

pH 7.4), the carboxyl group is dissociated, forming the negatively

charged carboxylate ion (– COO–), and the amino group is protonated

(– NH3+). In proteins, almost all of these carboxyl and amino groups are

combined through peptide linkage and, in general, are not available for

chemical reaction except for hydrogen bond formation (Figure 1.1B).

Thus, it is the nature of the side chains that ultimately dictates the role

A

Free amino acid

Common to all α-amino

acids of proteins

C OH

CO

COOH

+H N

3

Cα H

R

Amino

group

Side chain

is distinctive

for each amino

acid.

Carboxyl

group

α-Carbon is

between the

carboxyl and the

amino groups.

Amino acids combined

B through

peptide linkages

NH-CH-CO-NH-CH-CO

R

R

Side chains determine

properties of proteins.

Figure 1.1

Structural features of amino acids

(shown in their fully protonated form).

1

168397_P001-012.qxd7.0:02 Protein structure 5-20-04

2010.4.4

9:45 AM

Page 2

2

1. Amino Acids

an amino acid plays in a protein. It is, therefore, useful to classify the

amino acids according to the properties of their side chains, that is,

whether they are nonpolar (have an even distribution of electrons) or

polar (have an uneven distribution of electrons, such as acids and

bases; Figures 1.2 and 1.3).

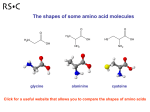

A. Amino acids with nonpolar side chains

Each of these amino acids has a nonpolar side chain that does not

gain or lose protons or participate in hydrogen or ionic bonds

(Figure 1.2). The side chains of these amino acids can be thought of

as “oily” or lipid-like, a property that promotes hydrophobic interactions (see Figure 2.10, p. 19).

1. Location of nonpolar amino acids in proteins: In proteins found in

aqueous solutions––a polar environment––the side chains of the

nonpolar amino acids tend to cluster together in the interior of the

protein (Figure 1.4). This phenomenon, known as the hydrophobic

NONPOLAR SIDE CHAINS

COOH

+H N

3

C

H

+H

3N C

H

H

Glycine

H

CH2

C

H3C

CH

CH3

C

H

H

C

CH3

Leucine

H3N C H

COOH

+H

3N

H

CH2

CH3

Isoleucine

Phenylalanine

COOH

+H N

3

C

COOH

H

CH2

CH2

+H N

2

C

CH2

H2C

CH

S

Tryptophan

C

CH2

COOH

+

H

Valine

COOH

+H N

3

CH

H3C

CH3

N

H

3N

Alanine

COOH

C

+H

CH3

pK2 = 9.6

+H N

3

COOH

COOH

pK1 = 2.3

C

CH2

CH2

H

CH3

Methionine

Proline

Figure 1.2

Classification of the 20 amino acids commonly found in proteins, according to the charge and polarity of their

side chains at acidic pH is shown here and continues in Figure 1.3. Each amino acid is shown in its fully protonated

form, with dissociable hydrogen ions represented in red print. The pK values for the α-carboxyl and α-amino

groups of the nonpolar amino acids are similar to those shown for glycine. (Continued in Figure 1.3.)

168397_P001-012.qxd7.0:02 Protein structure 5-20-04

2010.4.4

9:45 AM

Page 3

II. Structure of the Amino Acids

3

UNCHARGED POLAR SIDE CHAINS

pK1 = 2.2

COOH

+H N

3

COOH

+H N

3

C

H

H

C

OH

+H N

3

C

H

H

C

OH

H

C

OH

pK3 = 10.1

Tyrosine

COOH

+H N

3

H

C

CH2

C

CH2

NH2

COOH

H

CH2

O

CH2

Threonine

COOH

H

pK2 = 9.1

CH3

Serine

+H N

3

C

COOH

+H N

3

Asparagine

H

CH2

pK3 = 10.8

C

O

C

pK1 = 1.7

SH

pK2 = 8.3

NH2

Glutamine

Cysteine

ACIDIC SIDE CHAINS

pK1 = 2.1

COOH

+H

pK3 = 9.8

3N

C

COOH

pK3 = 9.7

H

+H

3N

H

CH2

CH2

C

O

C

CH2

OH

pK2 = 3.9

C

O

OH

pK2 = 4.3

Aspartic acid

BASIC SIDE CHAINS

pK1 = 2.2

pK1 = 1.8

pK3 = 9.2

pK2 = 9.2

COOH

+H N

3

C

+H

H

CH2

C

+HN

C

H

pK2 = 6.0

pK2 = 9.0

COOH

3N C

+H

H

3N

COOH

C

CH2

CH2

CH

CH2

CH2

NH

CH2

CH2

CH2

NH3+

N

pK3 = 10.5

H

H

C NH2+

pK3 = 12.5

NH2

Histidine

Lysine

Arginine

Figure 1.3

Classification of the 20 amino acids commonly found in proteins, according to the charge and polarity

of their side chains at acidic pH (continued from Figure 1.2).

168397_P001-012.qxd7.0:02 Protein structure 5-20-04

2010.4.4

9:45 AM

Page 4

4

1. Amino Acids

Nonpolar amino

acids ( ) cluster

in the interior of

soluble proteins.

Nonpolar amino

acids ( ) cluster

on the surface of

membrane proteins.

Cell

membrane

Polar amino acids

( ) cluster on

the surface of

soluble proteins.

Soluble protein

Membrane protein

Figure 1.4

Location of nonpolar amino acids

in soluble and membrane proteins.

Secondary amino

group

Primary amino

group

COOH

+H N

2

H2C

C

COOH

H

+H N

3

CH2

C

H

CH3

CH2

Alanine

Proline

Figure 1.5

Comparison of the secondary

amino group found in proline with

the primary amino group found

in other amino acids, such as

alanine.

+H N

3

COOH

C H

CH2

effect, is the result of the hydrophobicity of the nonpolar R-groups,

which act much like droplets of oil that coalesce in an aqueous

environment. The nonpolar R-groups thus fill up the interior of the

folded protein and help give it its three-dimensional shape.

However, for proteins that are located in a hydrophobic environment, such as a membrane, the nonpolar R-groups are found on

the outside surface of the protein, interacting with the lipid environment (see Figure 1.4). The importance of these hydrophobic

interactions in stabilizing protein structure is discussed on p. 19.

Sickle cell anemia, a sickling disease of red

blood cells, results from the substitution of polar

glutamate by nonpolar valine at the sixth position

in the β subunit of hemoglobin (see p. 36).

2. Proline: Proline differs from other amino acids in that proline’s

side chain and α-amino N form a rigid, five-membered ring structure (Figure 1.5). Proline, then, has a secondary (rather than a primary) amino group. It is frequently referred to as an imino acid.

The unique geometry of proline contributes to the formation of the

fibrous structure of collagen (see p. 45), and often interrupts the

α-helices found in globular proteins (see p. 26).

B. Amino acids with uncharged polar side chains

These amino acids have zero net charge at neutral pH, although the

side chains of cysteine and tyrosine can lose a proton at an alkaline

pH (see Figure 1.3). Serine, threonine, and tyrosine each contain a

polar hydroxyl group that can participate in hydrogen bond formation

(Figure 1.6). The side chains of asparagine and glutamine each

contain a carbonyl group and an amide group, both of which can

also participate in hydrogen bonds.

1. Disulfide bond: The side chain of cysteine contains a sulfhydryl

group (–SH), which is an important component of the active site

of many enzymes. In proteins, the –SH groups of two cysteines

can become oxidized to form a dimer, cystine, which contains a

covalent cross-link called a disulfide bond (–S–S–). (See p. 19 for

a further discussion of disulfide bond formation.)

Tyrosine

O

H

Carbonyl O

group C

Hydrogen

bond

Many extracellular proteins are stabilized by

disulfide bonds. Albumin, a blood protein that

functions as a transpor ter for a variety of

molecules, is an example.

2. Side chains as sites of attachment for other compounds: The

Figure 1.6

Hydrogen bond between the

phenolic hydroxyl group of tyrosine

and another molecule containing a

carbonyl group.

polar hydroxyl group of serine, threonine, and, rarely, tyrosine, can

serve as a site of attachment for structures such as a phosphate

group. In addition, the amide group of asparagine, as well as the

hydroxyl group of serine or threonine, can serve as a site of attachment for oligosaccharide chains in glycoproteins (see p. 165).

168397_P001-012.qxd7.0:02 Protein structure 5-20-04

2010.4.4

9:45 AM

Page 5

II. Structure of the Amino Acids

C. Amino acids with acidic side chains

The amino acids aspartic and glutamic acid are proton donors. At

physiologic pH, the side chains of these amino acids are fully ionized,

containing a negatively charged carboxylate group (–COO–). They are,

therefore, called aspartate or glutamate to emphasize that these amino

acids are negatively charged at physiologic pH (see Figure 1.3).

D. Amino acids with basic side chains

The side chains of the basic amino acids accept protons (see Figure

1.3). At physiologic pH the side chains of lysine and arginine are fully

ionized and positively charged. In contrast, histidine is weakly basic,

and the free amino acid is largely uncharged at physiologic pH.

However, when histidine is incorporated into a protein, its side chain

can be either positively charged or neutral, depending on the ionic

environment provided by the polypeptide chains of the protein. This

is an important property of histidine that contributes to the role it

plays in the functioning of proteins such as hemoglobin (see p. 31).

E. Abbreviations and symbols for commonly occurring amino acids

Each amino acid name has an associated three-letter abbreviation

and a one-letter symbol (Figure 1.7). The one-letter codes are determined by the following rules:

1. Unique first letter: If only one amino acid begins with a particular

letter, then that letter is used as its symbol. For example, I =

isoleucine.

2. Most commonly occurring amino acids have priority: If more

than one amino acid begins with a particular letter, the most common of these amino acids receives this letter as its symbol. For

example, glycine is more common than glutamate, so G = glycine.

3. Similar sounding names: Some one-letter symbols sound like the

amino acid they represent. For example, F = phenylalanine, or W

= tryptophan (“twyptophan” as Elmer Fudd would say).

4. Letter close to initial letter: For the remaining amino acids, a one-

letter symbol is assigned that is as close in the alphabet as possible to the initial letter of the amino acid, for example, K = lysine.

Furthermore, B is assigned to Asx, signifying either aspartic acid

or asparagine, Z is assigned to Glx, signifying either glutamic acid

or glutamine, and X is assigned to an unidentified amino acid.

F. Optical properties of amino acids

The α-carbon of an amino acid is attached to four different chemical

groups and is, therefore, a chiral or optically active carbon atom.

Glycine is the exception because its α-carbon has two hydrogen

substituents and, therefore, is optically inactive. Amino acids that

have an asymmetric center at the α-carbon can exist in two forms,

designated D and L, that are mirror images of each other (Figure

1.8). The two forms in each pair are termed stereoisomers, optical

isomers, or enantiomers. All amino acids found in proteins are of the

L-configuration. However, D-amino acids are found in some antibiotics and in plant and bacterial cell walls. (See p. 253 for a discussion of D-amino acid metabolism.)

5

1

Unique first letter:

Cysteine

Histidine

Isoleucine

Methionine

Serine

Valine

2

C

H

I

=

=

=

=

=

=

M

S

V

=

=

=

=

=

Ala

Gly

Leu

Pro

Thr

A

=

=

=

=

=

G

L

P

T

Similar sounding names:

Arginine

Asparagine

Aspartate

Glutamate

Glutamine

Phenylalanine

Tyrosine

Tryptophan

4

Cys

His

Ile

Met

Ser

Val

Most commonly occurring

amino acids have priority:

Alanine

Glycine

Leucine

Proline

Threonine

3

=

=

=

=

=

=

=

=

=

=

=

=

=

=

Arg

Asn

Asp

Glu

Gln

Phe

Tyr

Trp

=

=

=

=

=

=

=

=

R

N

D

E

(“aRginine”)

(contains N)

("asparDic")

("glutEmate")

Q (“Q-tamine”)

F (“Fenylalanine”)

Y (“tYrosine”)

W (double ring in

the molecule)

Letter close to initial letter:

Aspartate or

asparagine

Glutamate or

glutamine

Lysine

Undetermined

amino acid

=

Asx =

B (near A)

=

Glx =

Z

=

=

Lys =

K (near L)

X

Figure 1.7

Abbreviations and symbols for the

commonly occurring amino acids.

OH

CO

H

C

+H3N

CH3

e

nin

-Ala

L

HO

OC

H C

N

H C H3+

3

D-A

lan

ine

Figure 1.8

D and L forms of alanine

are mirror images.

168397_P001-012.qxd7.0:02 Protein structure 5-20-04

2010.4.4

9:45 AM

Page 6

6

1. Amino Acids

III. ACIDIC AND BASIC PROPERTIES OF AMINO ACIDS

Amino acids in aqueous solution contain weakly acidic α-carboxyl

groups and weakly basic α-amino groups. In addition, each of the acidic

and basic amino acids contains an ionizable group in its side chain.

Thus, both free amino acids and some amino acids combined in

peptide linkages can act as buffers. Recall that acids may be defined as

proton donors and bases as proton acceptors. Acids (or bases)

described as “weak” ionize to only a limited extent. The concentration of

protons in aqueous solution is expressed as pH, where pH = log 1/[H+]

or –log [H+]. The quantitative relationship between the pH of the solution and concentration of a weak acid (HA) and its conjugate base (A–)

is described by the Henderson-Hasselbalch equation.

OH–

H20

CH3COOH

A. Derivation of the equation

FORM I

(acetic acid, HA)

FORM II

H+ (acetate, A– )

Buffer region

[II] > [I]

1.0

Equivalents OH– added

Consider the release of a proton by a weak acid represented by HA:

CH3COO–

[I] = [II]

HA

weak

acid

Ka

pKa = 4.8

[I] > [II]

0

3

4

5

6

pH

Figure 1.9

Titration curve of acetic acid.

H+

proton

7

A–

salt form

or conjugate base

+

The “salt” or conjugate base, A–, is the ionized form of a weak acid.

By definition, the dissociation constant of the acid, Ka, is

0.5

0

→

←

[H+] [A–]

[HA]

[Note: The larger the Ka, the stronger the acid, because most of the

HA has dissociated into H+ and A–. Conversely, the smaller the Ka,

the less acid has dissociated and, therefore, the weaker the acid.]

By solving for the [H+] in the above equation, taking the logarithm of

both sides of the equation, multiplying both sides of the equation by

–1, and substituting pH = – log [H+ ] and pKa = – log Ka, we obtain

the Henderson-Hasselbalch equation:

pH

pKa + log

[A– ]

[HA]

B. Buffers

A buffer is a solution that resists change in pH following the addition of

an acid or base. A buffer can be created by mixing a weak acid (HA) with

its conjugate base (A–). If an acid such as HCl is then added to such a

solution, A– can neutralize it, in the process being converted to HA. If a

base is added, HA can neutralize it, in the process being converted to

A–. Maximum buffering capacity occurs at a pH equal to the pKa, but a

conjugate acid/base pair can still serve as an effective buffer when the

pH of a solution is within approximately ±1 pH unit of the pKa. If the

168397_P001-012.qxd7.0:02 Protein structure 5-20-04

2010.4.4

9:45 AM

Page 7

III. Acidic and Basic Properties of Amino Acids

OH–

7

OH–

H20

COOH

+H N C H

3

–

H20

COO

+H N C H

3

CH3

H+

FORM I

pK1 = 2.3

CH3

FORM II

–

COO

H2N C H

H+

pK2 = 9.1

CH3

FORM III

Alanine in acid solution

(pH less than 2)

Alanine in neutral solution

(pH approximately 6)

Alanine in basic solution

(pH greater than 10)

Net charge = +1

Net charge = 0

(isoelectric form)

Net charge = –1

Figure 1.10

Ionic forms of alanine in acidic, neutral, and basic solutions.

amounts of HA and A– are equal, the pH is equal to the pKa. As shown in

Figure 1.9, a solution containing acetic acid (HA = CH3 – COOH) and

acetate (A– = CH3 – COO–) with a pKa of 4.8 resists a change in pH from

pH 3.8 to 5.8, with maximum buffering at pH 4.8. At pH values less than

the pKa, the protonated acid form (CH3 – COOH) is the predominant

species. At pH values greater than the pKa, the deprotonated base form

(CH3 – COO–) is the predominant species in solution.

C. Titration of an amino acid

1. Dissociation of the carboxyl group: The titration curve of an

amino acid can be analyzed in the same way as described for

acetic acid. Consider alanine, for example, which contains both

an α-carboxyl and an α-amino group. At a low (acidic) pH, both of

these groups are protonated (shown in Figure 1.10). As the pH of

the solution is raised, the – COOH group of Form I can dissociate

by donating a proton to the medium. The release of a proton

results in the formation of the carboxylate group, – COO–. This

structure is shown as Form II, which is the dipolar form of the

molecule (see Figure 1.10). This form, also called a zwitterion, is

the isoelectric form of alanine, that is, it has an overall (net)

charge of zero.

2. Application of the Henderson-Hasselbalch equation: The dissoci-

ation constant of the carboxyl group of an amino acid is called K1,

rather than Ka, because the molecule contains a second titratable

group. The Henderson-Hasselbalch equation can be used to

analyze the dissociation of the carboxyl group of alanine in the

same way as described for acetic acid:

K1

[H+] [II]

[I]

where I is the fully protonated form of alanine, and II is the isoelectric form of alanine (see Figure 1.10). This equation can be

rearranged and converted to its logarithmic form to yield:

168397_P001-012.qxd7.0:02 Protein structure 5-20-04

2010.4.4

9:45 AM

Page 8

8

1. Amino Acids

pH

pK1 + log

[II]

[I]

3. Dissociation of the amino group: The second titratable group of

COO

H2N C H

alanine is the amino (– NH3+) group shown in Figure 1.10. This is

a much weaker acid than the – COOH group and, therefore, has a

much smaller dissociation constant, K2. [Note: Its pKa is therefore

larger.] Release of a proton from the protonated amino group of

Form II results in the fully deprotonated form of alanine, Form III

(see Figure 1.10).

–

CH3

4. pKs of alanine: The sequential dissociation of protons from the

FORM III

Region of

buffering

Region of

buffering

[II] = [III]

Equivalents OH– added

2.0

pI = 5.7

1.5

1.0

5. Titration curve of alanine: By applying the Hender son-

[I] = [II]

pK

p

K2 = 9.

9.1

pK1 = 2.3

0.5

0

0

2

4

6

8

10

pH

p

COOH

+H N C H

3

CH3

carboxyl and amino groups of alanine is summarized in Figure

1.10. Each titratable group has a pKa that is numerically equal to

the pH at which exactly one half of the protons have been

removed from that group. The pK a for the most acidic group

(–COOH) is pK1, whereas the pKa for the next most acidic group

(– NH3+) is pK2.

COO

3N C H

–

+H

CH3

Hasselbalch equation to each dissociable acidic group, it is possible to calculate the complete titration curve of a weak acid. Figure

1.11 shows the change in pH that occurs during the addition of

base to the fully protonated form of alanine (I) to produce the

completely deprotonated form (III). Note the following:

a. Buffer pairs: The – COOH/– COO– pair can serve as a buffer in

the pH region around pK 1, and the – NH 3+/– NH 2 pair can

buffer in the region around pK2.

b. When pH = pK: When the pH is equal to pK 1 (2.3), equal

FORM II

amounts of Forms I and II of alanine exist in solution. When

the pH is equal to pK2 (9.1), equal amounts of Forms II and III

are present in solution.

Figure 1.11

The titration curve of alanine.

c. Isoelectric point: At neutral pH, alanine exists predominantly

FORM I

as the dipolar Form II in which the amino and carboxyl groups

are ionized, but the net charge is zero. The isoelectric point

(pI) is the pH at which an amino acid is electrically neutral, that

is, in which the sum of the positive charges equals the sum of

the negative charges. For an amino acid, such as alanine, that

has only two dissociable hydrogens (one from the α-carboxyl

and one from the α-amino group), the pI is the average of pK1

and pK2 (pI = [2.3 + 9.1]/2 = 5.7, see Figure 1.11). The pI is

thus midway between pK1 (2.3) and pK2 (9.1). pI corresponds

to the pH at which the Form II (with a net charge of zero) predominates, and at which there are also equal amounts of

Forms I (net charge of +1) and III (net charge of –1).

168397_P001-012.qxd7.0:02 Protein structure 5-20-04

2010.4.4

9:45 AM

Page 9

III. Acidic and Basic Properties of Amino Acids

Separation of plasma proteins by charge typically

is done at a pH above the pI of the major proteins, thus, the charge on the proteins is negative.

In an electric field, the proteins will move toward

the positive electrode at a rate determined by

their net negative charge. Variations in the mobility pattern are suggestive of certain diseases.

9

A

pH = pK + log

D. Other applications of the Henderson-Hasselbalch equation

The Henderson-Hasselbalch equation can be used to calculate how

the pH of a physiologic solution responds to changes in the concentration of a weak acid and/or its corresponding “salt” form. For example, in the bicarbonate buffer system, the Henderson-Hasselbalch

equation predicts how shifts in the bicarbonate ion concentration,

[HCO3–], and CO2 influence pH (Figure 1.12A). The equation is also

useful for calculating the abundance of ionic forms of acidic and

basic drugs. For example, most drugs are either weak acids or weak

bases (Figure 1.12B). Acidic drugs (HA) release a proton (H+), causing a charged anion (A–) to form.

→

←

HA

Pulmonary obstruction causes an

increase in carbon dioxide and

causes the pH to fall, resulting

in respiratory acidosis.

LUNG

ALVEOLI

CO2 + H2O

B

H2CO3

BH

→

←

H+ + HCO3-

DRUG ABSORPTION

–

pH = pK + log [Drug ]

[Drug-H]

At the pH of the stomach (1.5), a

drug like aspirin (weak acid,

pK = 3.5) will be largely protonated

(COOH) and, thus, uncharged.

Uncharged drugs generally cross

membranes more rapidly than

charged molecules.

STOMACH

H+ + A–

Weak bases (BH+) can also release a H+. However, the protonated

form of basic drugs is usually charged, and the loss of a proton produces the uncharged base (B).

+

[HCO3– ]

[CO2]

An increase in HCO3–

causes the pH to rise.

6. Net charge of amino acids at neutral pH: At physiologic pH,

amino acids have a negatively charged group (– COO–) and a

positively charged group (– NH3+), both attached to the α-carbon.

[Note: Glutamate, aspartate, histidine, arginine, and lysine have

additional potentially charged groups in their side chains.]

Substances, such as amino acids, that can act either as an acid

or a base are defined as amphoteric, and are referred to as

ampholytes (amphoteric electrolytes).

BICARBONATE AS A BUFFER

B+ H

+

A drug passes through membranes more readily if it is uncharged.

Thus, for a weak acid such as aspirin, the uncharged HA can permeate through membranes and A– cannot. For a weak base, such

as morphine, the uncharged form, B, penetrates through the cell

membrane and BH+ does not. Therefore, the effective concentration

of the permeable form of each drug at its absorption site is determined by the relative concentrations of the charged and uncharged

forms. The ratio between the two forms is determined by the pH at

the site of absorption, and by the strength of the weak acid or base,

which is represented by the pK a of the ionizable group. The

Henderson-Hasselbalch equation is useful in determining how much

drug is found on either side of a membrane that separates two compartments that differ in pH, for example, the stomach (pH 1.0–1.5)

and blood plasma (pH 7.4).

Lipid

membrane

H+

AH+

HA

H+

AH+

HA

LUMEN OF

STOMACH

BLOOD

Figure 1.12

The Henderson-Hasselbalch

equation is used to predict: A,

changes in pH as the concentrations

of HCO3– or CO2 are altered;

or B, the ionic forms of drugs.

168397_P001-012.qxd7.0:02 Protein structure 5-20-04

2010.4.4

9:45 AM

Page 10

10

1. Amino Acids

A Linked concept boxes

Amino acids

(fully protonated)

can

Release H+

cross-linked

B Concepts

within a map

Degradation

of body

protein

is produced by

Simultaneous

synthesis and

degradation

Amino

acid

pool

Protein

turnover

leads to

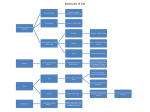

IV. CONCEPT MAPS

Students sometimes view biochemistry as a blur of facts or equations to

be memorized, rather than a body of concepts to be understood. Details

provided to enrich understanding of these concepts inadvertently turn

into distractions. What seems to be missing is a road map—a guide that

provides the student with an intuitive understanding of how various topics fit together to make sense. The authors have, therefore, created a

series of biochemical concept maps to graphically illustrate relationships

between ideas presented in a chapter, and to show how the information

can be grouped or organized. A concept map is, thus, a tool for visualizing the connections between concepts. Material is represented in a hierarchic fashion, with the most inclusive, most general concepts at the top

of the map, and the more specific, less general concepts arranged

beneath. The concept maps ideally function as templates or guides for

organizing information, so the student can readily find the best ways to

integrate new information into knowledge they already possess.

A. How is a concept map constructed?

1. Concept boxes and links: Educators define concepts as “per-

Synthesis

of body

protein

is consumed by

Amino

acid

pool

C Concepts cross-linked

to other chapters and

to other books in the

Lippincott Series

. . . how the

protein folds

into its native

conformation

Structure

of Proteins

2

. . . how altered

protein folding

leads to prion

disease, such

as CreutzfeldtJakob disease

Lippincott's

Illustrated

Reviews

gy

o

l

io

b

ro

ic

M

Figure 1.13

Symbols used in concept maps.

ceived regularities in events or objects.” In our biochemical maps,

concepts include abstractions (for example, free energy), processes (for example, oxidative phosphorylation), and compounds

(for example, glucose 6-phosphate). These broadly defined concepts are prioritized with the central idea positioned at the top of

the page. The concepts that follow from this central idea are then

drawn in boxes (Figure 1.13A). The size of the type indicates the

relative importance of each idea. Lines are drawn between concept boxes to show which are related. The label on the line

defines the relationship between two concepts, so that it reads as

a valid statement, that is, the connection creates meaning. The

lines with arrowheads indicate in which direction the connection

should be read (Figure 1.14).

2. Cross-links: Unlike linear flow charts or outlines, concept maps

may contain cross-links that allow the reader to visualize complex

relationships between ideas represented in different parts of the

map (Figure 1.13B), or between the map and other chapters in

this book or companion books in the series (Figure 1.13C). Crosslinks can thus identify concepts that are central to more than one

discipline, empowering students to be effective in clinical situations, and on the United States Medical Licensure Examination

(USMLE) or other examinations, that bridge disciplinary boundaries. Students learn to visually perceive nonlinear relationships

between facts, in contrast to cross-referencing within linear text.

V. CHAPTER SUMMARY

Each amino acid has an α-carboxyl group and a primary α-amino

group (except for proline, which has a secondary amino group). At

physiologic pH, the α-carboxyl group is dissociated, forming the negatively charged carboxylate ion (– COO–), and the α-amino group is protonated (– NH3+). Each amino acid also contains one of 20 distinctive

168397_P001-012.qxd7.0:02 Protein structure 5-20-04

2010.4.4

9:45 AM

Page 11

V. Chapter Summary

11

Amino acids

are composed of

α-Carboxyl group

(–COOH)

α-Amino group

(–NH2)

when protonated can

Side chains

(20 different ones)

Release H

+

and act as

is

is

Deprotonated (COO–)

at physiologic pH

Protonated (NH3+ )

at physiologic pH

Weak acids

grouped as

described by

Henderson-Hasselbalch

equation:

[A–]

pH = pKa + log

[HA]

Nonpolar

side chains

Alanine

Glycine

Isoleucine

Leucine

Methionine

Phenylalanine

Proline

Tryptophan

Valine

Uncharged polar

side chains

Asparagine

Cysteine

Glutamine

Serine

Threonine

Tyrosine

Acidic

side chains

Aspartic acid

Glutamic acid

characterized by

Side chain dissociates

to –COO– at

physiologic pH

Basic

side chains

predicts

Arginine

Histidine

Lysine

Buffering capacity

predicts

characterized by

Side chain is protonated and

generally has a

positive charge

at physiologic pH

Buffering occurs

±1 pH unit of pKa

predicts

found

found

found

found

Maximal buffer

when pH = pKa

On the outside of proteins that function in an aqueous environment

and in the interior of membrane-associated proteins

predicts

In the interior of proteins that function

in an aqueous environment and on

the surface of proteins (such as membrane

proteins) that interact with lipids

In proteins, most

α-COO– and

α-NH3+ of amino

acids are

combined through

peptide bonds.

Therefore, these

groups are not

available for

chemical reaction.

Figure 1.14

Key concept map for amino acids.

pH = pKa when [HA] = [A– ]

Thus, the chemical

nature of the side

chain determines

the role that the

amino acid plays

in a protein,

particularly . . .

Structure

of Proteins

. . . how the

protein folds

into its native

conformation.

2

168397_P001-012.qxd7.0:02 Protein structure 5-20-04

2010.4.4

12

9:45 AM

Page 12

1. Amino Acids

side chains attached to the α-carbon atom. The chemical nature of this side chain determines the function of

an amino acid in a protein, and provides the basis for classification of the amino acids as nonpolar ,

uncharged polar, acidic, or basic. All free amino acids, plus charged amino acids in peptide chains, can serve

as buffers. The quantitative relationship between the pH of a solution and the concentration of a weak acid

(HA) and its conjugate base (A–) is described by the Henderson-Hasselbalch equation. Buffering occurs

within ±1pH unit of the pKa, and is maximal when pH = pKa, at which [A–] = [HA]. The α-carbon of each amino

acid (except glycine) is attached to four different chemical groups and is, therefore, a chiral or optically active

carbon atom. Only the L-form of amino acids is found in proteins synthesized by the human body.

Study Questions

Choose the ONE correct answer.

Equivalents OH– added

1.1 The letters A through E designate certain regions on

the titration curve for glycine (shown below). Which

one of the following statements concerning this curve

is correct?

E

2.0

D

1.5

1.0

C

0.5

B

A

0

0

2

4

6

8

Correct answer = C. C represents the isoelectric

point or pI, and as such is midway between pK1

and pK 2 for this monoamino monocarboxylic

acid. Glycine is fully protonated at Point A. Point

B represents a region of maximum buffering, as

does Point D. Point E represents the region

where glycine is fully deprotonated.

10

pH

A. Point A represents the region where glycine is

deprotonated.

B. Point B represents a region of minimal buffering.

C. Point C represents the region where the net charge

on glycine is zero.

D. Point D represents the pK of glycine’s carboxyl

group.

E. Point E represents the pI for glycine.

1.2 Which one of the following statements concerning the

peptide shown below is correct?

Gly-Cys-Glu-Ser-Asp-Arg-Cys

A. The peptide contains glutamine.

B. The peptide contains a side chain with a secondary

amino group.

C. The peptide contains a majority of amino acids with

side chains that would be positively charged at pH 7.

D. The peptide is able to form an internal disulfide

bond.

1.3 Given that the pI for glycine is 6.1, to which electrode,

positive or negative, will glycine move in an electric

field at pH 2? Explain.

Correct answer = D. The two cysteine residues

can, under oxidizing conditions, form a disulfide

bond. Glutamine’s 3-letter abbreviation is Gln.

Proline (Pro) contains a secondary amino group.

Only one (Arg) of the seven would have a positively charged side chain at pH 7.

Correct answer = negative electrode. When the

pH is less than the pI, the charge on glycine is

positive because the α-amino group is fully protonated. (Recall that glycine has H as its R

group).