* Your assessment is very important for improving the work of artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download An action plan to prevent and combat threadworm

Survey

Document related concepts

Transcript

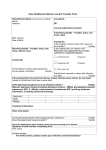

NTCLINICAL NT CLINICAL is an essential resource for extending your knowledge base. You can achieve your continuing professional development PREP requirements by reflecting on these articles. 00 UPDATE An action plan to prevent and combat threadworm infection AUTHOR Janet Blake, BA, RGN, is community nurse, Kingston Hospital, Surrey. ABSTRACT Blake, J. (2003) An action plan to prevent and combat threadworm infection. Nursing Times; 99: 42, 18–19. Threadworm infection is common in preschool and school-age children and is easily spread to the entire family. The infection can be treated using medication, which should be taken by all members of the family, but good hygiene measures are equally important to ensure reinfection does not occur. Threadworm infection is especially common in preschool and school-age children, but can spread to the entire family. People in every socioeconomic group are at risk of contracting the infection (Russell, 1991). Around 40 per cent of children under the age of 10 are likely to have threadworms at some stage. At least 20 per cent of all children are affected at any one time. Nearly half the parents who report threadworm infection in their child report repeat infection in the same year (Ibarra,1989). Threadworms (pinworms) are known as Enterobius vermicularis. They look like pieces of white cotton thread and live in the rectum of humans. They are harmless. If they are infected, children can continue to attend nursery school or school, but parents should inform the school that the infection is being treated. Transmission Threadworms are transmitted via eggs on the fingers and under the fingernails. Following contact between the hands and the mouth, eggs hatch and larvae are released into the small intestine (Box 1). The female adult worm deposits eggs just outside the anus at night, which causes itching. Scratching results in the collection of eggs on the fingers and under the fingernails. The entire process of transfer will then be easily repeated. The eggs can be spread among family members through sharing bath towels. They can survive for a couple of weeks on clothing, bedding and in general household dust. A family pet is never responsible. The only host for threadworms is a human. The symptoms and consequences of infection The main symptom of the infection is a tickling or itching of the anal area at night. Sleep may be disturbed and some children develop sore bottoms. Usually worms are only seen in the toilet, if at all. Many people who have the infection will show no symptoms. In a study of 172 Swedish children aged 4–10, 41 children (24 per cent) had a positive tape-test for the eggs but only five of them had symptoms. Thus 21 per cent of the children studied were symptom-free carriers of the worm (Herrström et al, 1997). Although complications of threadworm infection are very rare, nurses should be alert to what has been reported in the scientific literature. The most common complication is bacterial infection of the skin around the anus. In girls and women worms may migrate from the skin around the anus over the perineum to enter the vagina. Threadworms or eggs have been found in routine vaginal and cervical smears (Chung et al, 1997), and in peritoneal granulomas (Sun et al, 1991). Urinary tract infections, especially in girls, can be related to threadworms (Kropp et al, 1978). There is a possible relationship between the infection and enuresis. Diagnosis If there is any doubt about the diagnosis, then a test using transparent adhesive tape to collect eggs around the anus may be done. The presence of the eggs can be confirmed by microscope. The standard test has changed very little since it was developed (Jones, 1988; Jacobs, 1942). It should be done early in the day before the patient washes the anal area after rising. If infection is mild, it may be necessary to carry out tests over three or four mornings. The patient or parent may take samples themselves on the second and subsequent BOX 1. THREADWORM INFECTION FACT LIST ● At least 20 per cent of all children are affected by threadworms at any one time ● Threadworms live in the rectum of humans ● The female worms lay their eggs on the skin around the anus at night ● ‘Itchy bottom’ is the most common symptom, but symptoms may be absent ● Eggs on the fingers and under nails transfer to people and clothing and are swallowed ● Eggs can survive for up to two weeks on clothing, towels, bedding, in carpets and in dust ● Piperazine and mebendazole are both effective treatments of the disease ● Drug treatment must be combined with hygienic measures to prevent reinfection NT 21 October 2003 Vol 99 No 42 www.nursingtimes.net KEYWORDS BOX 2. THREADWORM ACTION DAY BOX 3. PREVENTING REINFECTION Threadworm Action Day will be held on 22 October and provides nurses with an opportunity to promote general infection control routines. Fred Worm is a friendly cartoon character that will be used to engage children and help put adults at ease by discussing the problem. Visit www.fredworm.com ● Keep ■ Public health ■ Threadworms ■ Treatment the nails short ● Wash hands and scrub nails before every meal or snack and after using the toilet ● Bath or shower every morning (removes eggs laid at night) Chung, D.I. et al (2003) Live Enterobius vermicularis in the posterior fornix of the vagina of a Korean woman. Korean Journal of Parasitology; 35: 67–69. Ibarra, J. (1989) Towards a viable approach to the thread-worm problem. Health at School; 5: 54–57. ● Wear occasions, bringing the tape to the nurse in sealed bags. An alternative method is to trap a few of the worms when they come out of the anus at night (Ibarra, 2001). Hypoallergenic tape pressed against the anus as the child goes to bed, with snugly fitting underpants to hold the tape in place make a suitable worm trap. Alternatively, petroleum jelly used in the same way may collect worms overnight. The samples should be kept in a plastic bag to be viewed by the nurse. Drug treatment Medication is necessary to remove the infection. It is available over the counter or on prescription. Effective drug treatments for threadworm include piperazine (paralyses the worms which are then expelled in the faeces) and/or mebendazole (prevents sugar absorption by the worms resulting in their death in a few days). Piperazine is the most common drug used in the UK for the treatment of threadworm infection, and may come combined with a mild laxative to help clear the paralysed worms quickly. A second dose is given 14 days later to ensure that any worms that were unhatched at the time of the first dose will be cleared from the system. Strict hygienic measures should be taken to prevent re-infection. It is best to treat the entire family on the same day. For people who are unable or unwilling to receive the drug treatment, such as pregnant mothers, the infection can be cleared by strict hygiene combined with mechanical removal (see other treatment options) of the eggs throughout the day until all the worms die or are cleared from the system. Contraindications A woman who is pregnant, planning a pregnancy or breastfeeding should see her GP before embarking on a treatment regimen, as should anyone who has a neurological disease. Similarly, children under two years of age will need to be seen by a doctor before they are treated with drugs. Any patient who is suspected of having roundworm infection or other secondary infestations should also be referred to a GP. Mebendazole is not for children under two. People should not be treated with piperazine if they have epilepsy, a gut blockage, liver disease or severely decreased kidney function. Check that the patient is not allergic to any of the components. NT 21 October 2003 Vol 99 No 42 www.nursingtimes.net pyjamas or pants in bed (clean ones every night) REFERENCES ● Change underwear every day ● Disinfect the toilet seat, toilet handle, and door handle regularly ● Damp dust and vacuum bedrooms daily ● Towels should not be shared Providing reassurance and advice The nurse is probably the health professional best suited to minimise the embarrassment of discussing ‘itchy bottoms’ and to ensure that the necessary hygienic practices are effectively communicated to a family. Parents, especially parents new to this problem such as parents of toddlers, can feel guilt and humiliation. They need to be reassured that they are not failing as parents and are not running a shamefully dirty household (Box 2). Other treatment options Mechanical removal of the eggs may be the only treatment option for some individuals. Measures to remove eggs include (Ibarra, 2001): ● The application of tape or jelly around the anus at night, followed by washing or wet-wiping the perianal area after rising from bed and at three-hourly intervals during the day; ● For babies, nappies should be changed and bottoms cleaned every three hours. Frequency is important as the larvae contained inside the eggs develop in 4–6 hours and some may hatch and migrate back into the rectum. ● Combining these measures with good hygiene can end the infection naturally after 2–3 weeks as the worms are expelled or die over that period. Preventing reinfection Good hygienic practices are listed in Box 3. Drug treatment must be combined with strict hygiene measures to prevent reinfection. Ibarra (2001) stresses that threadworm infection presents the opportunity for nurses to reinforce key personal hygiene measures. Not only will proper handwashing protect against threadworms, but also against a wide range of other infections, including gastroenteritis. She advocates that primary schools and nurseries should be encouraged to supervise handwashing until children are seven years old: ‘Good habits cheerfully established in the early years will set a child up for life.’ ■ Ibarra, J. (2001) Threadworms: a starting point for family hygiene. British Journal of Community Nursing; 6: 8, 414–420. Jacobs, A.H. (1942) Enterobiasis in children: incidence symptomatology and diagnosis with a simplified Scotch cellulose tape technique. Journal of Paediatrics; 21: 497–503. Jones, J. (1988) Pinworms. American Family Physician; 38: 159–164. Herrström, P. et al (1997) Enterobius vermicularis and finger sucking in young Swedish children. Scandinavian Journal of Primary Health Care; 15: 146–148. Kropp, K.A. et al (1978) Enterobius vermicularis (pinworms), introital bacteriology and recurrent urinary tract infection in children. Journal of Urology; 120: 480–482. Russell, L.J. (1991) The pinworm, Enterobius vermicularis. Primary Care; 18: 13–24. Sun, T. et al (1991) Enterobius egg granuloma of the vulva and peritoneum: review of the literature. The American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene; 45; 249–253. Mattia, A.R. (1992) Perianal mass and recurrent cellulites due to Enterobius vermicularis. The American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene; 47; 6, 811–815. This article has been double-blind peer-reviewed. For related articles on this subject and links to relevant websites see www. nursingtimes.net 19