* Your assessment is very important for improving the workof artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download The Health Profession Assistant: Consideration for the Dental

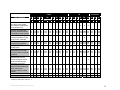

Survey

Document related concepts

Water fluoridation in the United States wikipedia , lookup

Dental implant wikipedia , lookup

Crown (dentistry) wikipedia , lookup

Amalgam (dentistry) wikipedia , lookup

Periodontal disease wikipedia , lookup

Forensic dentistry wikipedia , lookup

Remineralisation of teeth wikipedia , lookup

Focal infection theory wikipedia , lookup

Dental emergency wikipedia , lookup

Dentistry throughout the world wikipedia , lookup

Special needs dentistry wikipedia , lookup

Transcript