* Your assessment is very important for improving the workof artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

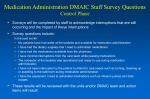

Download MEDICATION/POLYPHARMACY EFFECTS ON OLDER PERSONS

Survey

Document related concepts

Transcript