* Your assessment is very important for improving the work of artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download Infectious_Diseases - Geriatrics Care Online

Eradication of infectious diseases wikipedia , lookup

Onchocerciasis wikipedia , lookup

Hepatitis C wikipedia , lookup

Typhoid fever wikipedia , lookup

Dirofilaria immitis wikipedia , lookup

Human cytomegalovirus wikipedia , lookup

Tuberculosis wikipedia , lookup

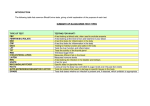

Clostridium difficile infection wikipedia , lookup

African trypanosomiasis wikipedia , lookup

Gastroenteritis wikipedia , lookup

Marburg virus disease wikipedia , lookup

Middle East respiratory syndrome wikipedia , lookup

Rocky Mountain spotted fever wikipedia , lookup

Hepatitis B wikipedia , lookup

Oesophagostomum wikipedia , lookup

Schistosomiasis wikipedia , lookup

Neonatal infection wikipedia , lookup

Traveler's diarrhea wikipedia , lookup

Leptospirosis wikipedia , lookup

Coccidioidomycosis wikipedia , lookup

INFECTIOUS DISEASES OBJECTIVES Know and understand: • Factors that influence immune function in elderly people • Ways in which infectious diseases may present atypically in older patients • Criteria for initiating antibiotic therapy for residents of long-term-care facilities • How to diagnose and manage infectious diseases that are common in the elderly Slide 2 TOPICS COVERED • Predisposition to infection • General principles for diagnosis and management of infections • Epidemiology, diagnosis, and management of specific infectious syndromes • Fever of unknown origin Slide 3 CONSEQUENCES OF INFECTION • Mortality—Infection is a major cause of death in older adults • Morbidity—Infection often exacerbates underlying illness or leads to hospitalization Infection 40% All other causes 60% Major cause of death in adults 65 years Slide 4 AGE-RELATED ALTERATIONS IN IMMUNE FUNCTION • Immune response declines with age, a phenomenon known as immune senescence • The main features are depressed T-cell responses and depressed T-cell/macrophage interactions • The most marked deficits of immunity in the elderly: Drying and thinning of the skin and mucous membranes Poor antibody production Decreased production of IL-2 and T-cell “help” Slide 5 IMPACT OF COMORBIDITY ON IMMUNE FUNCTION • The impact of comorbidities on innate immune function and host resistance is greater than the impact of age itself • Comorbid diseases also indirectly complicate infections (eg, community-acquired pneumonia in an elderly person with multiple comorbidities often requires hospitalization) Slide 6 IMPACT OF NUTRITIONAL STATUS ON IMMUNE FUNCTION • On hospital admission, global undernutrition is present in 30%–60% of patients 65 years • 11% of older outpatients suffer from undernutrition, mostly due to reversible conditions such as depression, poorly controlled diabetes mellitus, and medication side effects • Some nutritional interventions may boost immune function in older adults, but results vary with the population studied and the supplements used Slide 7 ATYPICAL PRESENTATION • Older adults may present without typical signs and symptoms, even if the infection is severe • Fever may be absent in 30%–50% of frail older adults with serious infections • Fever in elderly nursing-home residents can be redefined as: Temperature > 2°F (1.1°C) over baseline, or Oral temperature > 99°F (37.2°C) on repeated measures, or Rectal temperature > 99.5°F (37.5°C) on repeated measures Slide 8 ANTIBIOTIC MANAGEMENT • Drug distribution, metabolism, excretion, and interactions can be altered with age • Even in the absence of disease, aging is associated with a reduction in renal function • Antibiotic interactions occur with many medications commonly prescribed for elderly people • Risk factors for poor adherence include poor cognitive function, impaired hearing or vision, multiple medications, and financial constraints Slide 9 SUGGESTED MINIMUM CRITERIA FOR INITIATION OF ANTIBIOTIC THERAPY IN THE LONG-TERM-CARE SETTING (1 of 2) Condition Minimum Criteria Urinary tract infection, without catheter Fever AND one of the following: new or worsening urgency, frequency, suprapubic pain, gross hematuria, CVA tenderness, incontinence Urinary tract infection, with catheter Fever OR one of the following: new CVA tenderness, rigors, new-onset delirium Skin and soft-tissue infection Fever OR one of the following: redness, tenderness, warmth, new or increasing swelling of affected site Slide 10 SUGGESTED MINIMUM CRITERIA FOR INITIATION OF ANTIBIOTIC THERAPY IN THE LONG-TERM-CARE SETTING (2 of 2) Condition Minimum Criteria Respiratory infection Fever > 102°F (38.9°C) AND RR > 25 or productive cough Fever > 100 < 102°F AND RR > 25, pulse > 100, rigors, or new-onset delirium If afebrile but with COPD: new or increased cough with purulent sputum If afebrile without COPD: new or increased cough AND either RR > 25 or new-onset delirium Fever without source of infection New-onset delirium or rigors If antibiotics instituted as a diagnostic test (not recommended), discontinue in 3–5 days if no improvement and evaluation negative Slide 11 BACTEREMIA AND SEPSIS • Elderly patients with bacteremia are less likely than younger adults to have chills or sweating, and fever is commonly absent • GI and genitourinary sources of bacteremia are more common than in younger adults • Mortality rate with nosocomial gram-negative bacteremia: 5%–35% in younger adults, 37%–50% in elderly patients Slide 12 MANGEMENT OF BACTEREMIA AND SEPSIS • Similar in older and younger patients • Rapid administration of antibiotics aimed at the most likely sources is essential • Early “goal-directed” therapy for volume resuscitation has proven benefit • In septic adults age 75, adjunctive therapy with activated protein C has a survival benefit despite a slightly increased risk of serious bleeding Slide 13 PNEUMONIA: EPIDEMIOLOGY • Patients 65 account for over 50% of cases • Cumulative 2-year risk for long-term-care residents is about 30% • Mortality in elderly patients is 3 to 5 that of younger adults • Comorbidity is the strongest independent predictor of mortality Slide 14 CAUSES OF PNEUMONIA Slide 15 COMMUNITY-ACQUIRED PNEUMONIA Infectious Diseases Society of America guidelines suggest the following as first-line therapy for adults over 60, with or without comorbidity: • β-lactam/β-lactamase combination or advancedgeneration cephalosporin (ceftriaxone or cefotaxime), with or without a macrolide • Alternatively, one of the newer fluoroquinolones with enhanced activity against S. pneumoniae (levofloxacin, moxifloxacin, gemifloxacin) Slide 16 NURSING HOME AND HOSPITAL-ACQUIRED PNEUMONIA • Initial regimens should be broadly inclusive, followed by step-down therapy to narrower coverage if the causative agent is identified • For MRSA-colonized patients or patients in units with high rates of MRSA, initial regimens should include vancomycin or linezolid until MRSA is excluded • Patients with improving hospital-acquired pneumonia not caused by nonfermenting gram-negative bacilli (eg, Pseudomonas, Stenotrophomonas) can receive short courses of antibiotics (8 days) Slide 17 REDUCING THE RISK OF PNEUMONIA • Immunization • Smoking cessation • Aggressive treatment of comorbidities (eg, minimizing aspiration risk in post-stroke patients, limited use of sedative hypnotics) • System changes with attention to infection control may be particularly effective in the nursing home Slide 18 INFLUENZA • Annual influenza vaccination is recommended for all adults over 50 • Treatment with M2 inhibitors or neuraminidase inhibitors is most effective if initiated within 24 hours of symptom onset • Oseltamivir (oral) is easier to use than zanamivir (inhaled) • Older adults appeared to be less susceptible to the H1N1 pandemic of 2009 but are more likely to be hospitalized for H1N1 than younger adults Slide 19 URINARY TRACT INFECTION (UTI) • One of the most common illnesses in older adults • As in younger adults, gram-negative bacilli are most common • Older adults are more likely to have resistant isolates, such as Pseudomonas aeruginosa, and gram-positive organisms, including enterococci, coagulase-negative staphylococci, and Streptococcus agalactiae • Additional organisms in patients with indwelling catheters include enterococci, S. aureus, and fungi, particularly Candida spp. Slide 20 ASYMPTOMATIC BACTERURIA • Affects up to 15% of women in the community and 40% of women in nursing homes • Incidence in men is approximately half that in women • Treatment is not recommended No clinical benefit Associated with adverse effects, expense, potential for selection of resistant organisms Slide 21 LOWER-TRACT UTI (CYSTITIS) IN OLDER WOMEN • Characterized by dysuria, frequency, and urgency • 3‒7 days of therapy sufficient for uncomplicated cystitis • Fluoroquinolones (FQs) more efficacious than TMP-SMX in recent trials (TMP-SMX resistance usually >10%–20%) • Options in some settings are amoxicillin (particularly for enterococcal infection) and first-generation cephalosporins for patients with FQ intolerance • Culture not required unless first-line therapy fails Slide 22 UPPER-TRACT UTI (PYELONEPHRITIS) IN OLDER WOMEN • Characterized by fever, chills, nausea, and flank pain; commonly accompanied by lower-tract symptoms • Requires 7–21 days of therapy • Consider IV antibiotics for patients with suspected urosepsis, those with upper tract disease due to relatively resistant bacteria such as enterococci, and those unable to tolerate oral medications • Culture and sensitivity data should be obtained in most cases Slide 23 UTI IN OLDER MEN • Causative organisms and treatment choices are similar to those for older women • Usually due to obstructive prostatic disease or functional disability; 14 days of therapy needed • If prostatitis is suspected, 6 weeks of therapy is usually required • Culture and sensitivity data should guide therapy for virtually all UTIs in older men Slide 24 TUBERCULOSIS: EPIDEMIOLOGY • Patients 65 account for 25% of active cases in US • In long-term-care residents, prevalence of skin-test reactivity is 30%–50%, due to high rates of exposure in the early 1900s • Thus, most active cases in older adults are due to reactivation • Primary infection is of particular concern in nursinghome outbreaks Slide 25 TUBERCULOSIS: PRESENTATION • Older adults may present with fatigue, anorexia, decreased functional status, or low-grade fever instead of classic symptoms • Lung involvement common (75%); pneumonic processes in older adults should raise suspicion • Elderly patients are more likely than younger adults to have extrapulmonary disease • Virtually any body structure can be involved, and that organ system can account for the major presenting symptom Slide 26 TUBERCULOSIS: SKIN TESTING • Induration ≥15 mm 48 to 72 hours after placement of a 5-tuberculin-unit PPD indicates a positive test in all situations • Induration ≥10 mm is considered positive in nursinghome residents, recent converters (previous PPD <5 mm), immigrants from countries with high endemicity of TB, underserved US populations, and people with specific risk factors • Induration 5 mm is considered positive in HIVinfected patients, those with a history of close contact with people with active TB, and those with chest radiographs consistent with TB Slide 27 TUBERCULOSIS: MANAGEMENT • Treatment of active TB is similar to that in younger adults • Regardless of age, anyone with a positive PPD should be treated with isoniazid for 9 months if: They have never been treated in the past Active disease is excluded Slide 28 INFECTIVE ENDOCARDITIS • In the elderly, associated with degenerative valvular disorders and prosthetic valves • Age does not increase mortality risk • Treatment is IV antibiotics for 2–6 weeks • Consider surgery for severe valvular dysfunction, recurrent emboli, marked heart failure, myocardial abscess, fungal endocarditis, or failure of antibiotics to sterilize blood cultures Slide 29 AHA GUIDELINES FOR ENDOCARDITIS PROPHYLAXIS (1 of 3) • Cardiac conditions requiring prophylaxis Prosthetic cardiac valve Previous infective endocarditis Cardiac transplant recipients with cardiac valvulopathy Unrepaired cyanotic congenital heart disease Repaired congenital heart disease with residual defects at the site or adjacent to the site of a prosthetic patch or device Congenital heart disease completely repaired with prosthetic material or device (prophylaxis needed for only the first 6 mo after repair procedure) Slide 30 AHA GUIDELINES FOR ENDOCARDITIS PROPHYLAXIS (2 of 3) • Procedures warranting prophylaxis (only in patients with cardiac conditions listed on previous slide) Dental procedures requiring manipulation of gingival tissue, manipulation of the periapical region of teeth, or perforation of the oral mucosa (includes extractions, implants, reimplants, root canals, teeth cleaning during which bleeding is expected) Invasive procedures of the respiratory tract involving incision or biopsy of respiratory tract mucosa Surgical procedures involving infected skin, skin structures, or musculoskeletal tissue Slide 31 AHA GUIDELINES FOR ENDOCARDITIS PROPHYLAXIS (3 of 3) • Procedures not warranting prophylaxis All dental procedures not listed on previous slide All noninvasive respiratory procedures All gastrointestinal and genitourinary procedures Slide 32 ENDOCARDITIS PROPHYLAXIS REGIMENS Situation Regimen (Single Dose 30–60 Min Before Procedure)* Oral Amoxicillin 2 g po Unable to take oral medication Ampicillin 2 g, cefazolin 1 g, or ceftriaxone 1 g IM or IV Allergic to penicillins or ampicillin Cephalexin 2 g, clindamycin 600 mg, azithromycin 500 mg, or clarithromycin 500 mg po Allergic to penicillins or ampicillin and unable to take oral medication Cefazolin 1 g, ceftriaxone 1 g, or clindamycin 600 mg IM or IV Slide 33 PROSTHETIC DEVICE INFECTIONS • Device removal usually required for cure • Early and prolonged antibiotic intervention (for months), combined with aggressive surgical drainage, may be successful if symptoms have been present only for a brief duration • When full functionality is the goal, the best course is device removal and administration of antibiotics for 6–8 weeks, followed by reimplantation • Administration of prophylactic antibiotics other than for heart valves remains controversial Slide 34 SEPTIC ARTHRITIS • More likely in joints with underlying pathology • Early arthrocentesis is indicated in any mono- or oligoarticular syndrome, to exclude infection • S. aureus is the most likely pathogen • Aggressive antibiotic therapy should be combined with serial arthrocentesis in uncomplicated cases • Surgical drainage required when conservative strategy fails Slide 35 OSTEOMYELITIS • S. aureus is the predominant organism • GI and genitourinary flora are more common than in younger adults, so a specific microbiologic diagnosis is useful • Infections of pressure ulcers and diabetic foot infections commonly require surgical consultation plus aggressive antimicrobial therapy aimed at mixed aerobic and anaerobic bacteria Slide 36 HIV INFECTION AND AIDS • Heterosexual activity is the primary mode of infection in older adults • Untreated older adults progress to AIDS more rapidly than young adults, but response to HAART is similar • Management is similar to that used for younger adults, except that more aggressive CVD prevention is warranted • HIV is probably the most treatable infectious cause of dementia and much more likely to reverse with therapy than syphilis (which is more commonly tested) Slide 37 BACTERIAL MENINGITIS • Older adults account for most meningitis-associated fatalities • Ceftriaxone or cefotaxime, plus vancomycin, are recommended as empiric therapy until a specific isolate can be tested for antimicrobial susceptibility • Ampicillin is the drug of choice for Listeria spp. • More resistant gram-negative rods (eg, Pseudomonas spp.) require ceftazidime or an extended-spectrum penicillin, with or without intrathecal aminoglycoside therapy Slide 38 NEUROSYPHILIS • Possible underlying process in stroke or dementia; also consider in unilateral deafness, gait disturbances, uveitis, and optic neuritis • Positive CSF serology (VDRL test) may be diagnostic, but the sensitivity is only 75% in most series • Optimal treatment is penicillin G Slide 39 REACTIVATED VARICELLA ZOSTER VIRUS (HERPES ZOSTER, SHINGLES) • Advancing age is the major risk factor • The most disabling complication, postherpetic neuralgia, is common in older adults • Zoster vaccine is recommended for all immunocompetent adults ≥ 60 yr old and reduces the risk of zoster and post-herpetic neuralgia by >50% Slide 40 FACIAL NERVE PALSY (BELL’S PALSY) • Associated with at least 3 infectious causes: herpes simplex virus, varicella zoster virus, and Borrelia burgdorferi (which causes Lyme disease) • If facial nerve palsy occurs as part of an episode of varicella zoster virus, antiviral treatment is indicated and corticosteroids should be administered as well • If Lyme disease is suspected on a clinical basis: Oral amoxicillin, 500 mg four times per day for 14 days; or Oral doxycycline, 100 mg twice per day for 14 days; or IV ceftriaxone, 2 g per day for 14 days Slide 41 GASTROINTESTINAL INFECTIONS • Can present diagnostic dilemmas in the absence of fever or elevated WBC counts; a high index of suspicion is necessary • Diagnostic aids: Intra-abdominal infection—CT or labeled WBC study Cholecystitis, appendicitis, abscess—ultrasound Ischemic bowel—often requires angiography or flexible sigmoidoscopy • Treat infectious diarrhea as in younger adults Slide 42 CLOSTRIDIUM DIFFICILE INFECTION • Recent increase in incidence and severity, especially in older adults • First-line treatment: Metronidazole in mild to moderate disease Vancomycin in severe disease • Relapse is more common in older adults and may require tapering the vancomycin dose • Prevention: Reduce unneeded antibiotics and duration of needed antibiotic use Slide 43 FEVER OF UNKNOWN ORIGIN • Defined as temperature > 38.3°C (101°F) for at least 3 weeks, undiagnosed after 1 week of medical evaluation • About 35% of cases are due to treatable infections, especially intra-abdominal abscess, bacterial endocarditis, and tuberculosis • Collagen vascular diseases are more common causes than in younger patients (about 30% of cases) • Neoplastic disease accounts for another 20% of cases Slide 44 EVALUATING FEVER OF UNKNOWN ORIGIN IN OLDER ADULTS (1 of 2) 1. Confirm fever; conduct thorough history (include travel, MTB exposure, drugs, constitutional symptoms, symptoms of giant cell arteritis) and physical exam. Discontinue nonessential medications. 2. Initial laboratory evaluation: CBC with differential, liver enzymes, ESR, blood cultures 3, PPD skin testing, TSH, antinuclear antibody. Consider antineutrophilic cytoplasmic-antibody or HIVantibody testing. 3. a) Chest or abdomen or pelvic CT scan—if no obvious source; or b) Temporal artery biopsy—if symptoms or signs are consistent with giant cell arteritis or polymyalgia rheumatica and increased ESR; or c) Site-directed work-up on basis of symptoms or laboratory abnormalities, or both. Slide 45 EVALUATING FEVER OF UNKNOWN ORIGIN IN OLDER ADULTS (2 of 2) 4. If 3a is performed and no source is found, then 3b, and vice versa. 5. a) BM biopsy—yield best if hemogram abnormal—send for H&E, special stains, cultures, or b) Liver biopsy—very poor yield unless abnormal liver enzymes or hepatomegaly. 6. Indium-111 labeled white blood cell or gallium-67 scan—nuclear scans can effectively exclude infectious cause of FUO if negative. 7. Laparoscopy or exploratory laparotomy. 8. Empiric trial—typically reserved for antituberculosis therapy in rapidly declining host or high suspicion for tuberculosis (ie, prior positive PPD). Slide 46 SUMMARY • Immune function and host resistance are compromised in elderly people as a consequence of both immune senescence and comorbid disease • A redefinition of fever should be considered in the frail older patient • There are suggested criteria for initiating antibiotic therapy in residents of long-term-care facilities • Careful selection of first-line therapy is warranted in older patients with pneumonia Slide 47 CASE 1 (1 of 4) • A 79-year-old man in an assisted-living facility has cough, shortness of breath, and pleuritic chest pain. • He has a history of heart failure with bifascicular block and chronic kidney disease with a baseline creatinine of 1.8 mg/dL. • His medications are lisinopril, furosemide, and simvastatin. • On examination, he is awake and alert. Respiratory rate is 22 breaths per minute, temperature is 39.2°C (102.5°F), heart rate is 90 beats per minute, and blood pressure is 130/80 mmHg. Slide 48 CASE 1 (2 of 4) • Chest auscultation reveals crackles in the left lower lobe, and a chest radiograph shows an infiltrate. Community-acquired pneumonia is diagnosed, and the patient is admitted to the hospital. • His creatinine is now 3.5 mg/dL, with an estimated creatinine clearance of 20 mL/min. • Sputum for gram stain is not obtainable; a urine for Streptococcus pneumoniae and Legionella antigen detection is sent. Slide 49 CASE 1 (3 of 4) Which is the most appropriate initial antibiotic choice? (A) Moxifloxacin 200 mg/d (B) Ceftriaxone 1 gram/d plus azithromycin 500 mg/d (C) Levofloxacin 750 mg/d (D) Aztreonam 2 grams q8h plus vancomycin 1 gram q24h Slide 50 CASE 1 (4 of 4) Which is the most appropriate initial antibiotic choice? (A) Moxifloxacin 200 mg/d (B) Ceftriaxone 1 gram/d plus azithromycin 500 mg/d (C) Levofloxacin 750 mg/d (D) Aztreonam 2 grams q8h plus vancomycin 1 gram q24h Slide 51 CASE 2 (1 of 3) • A 78-year-old man comes to the office because he volunteers at the local hospital and is required to get a tuberculin skin test annually. • A tuberculosis skin test (PPD) using 5 tuberculin units was done a year ago when he started volunteering. At that time, the test was read as 4 mm of induration and interpreted as negative. • On retesting now, there is 16 mm of induration. He has no symptoms, and chest radiograph is negative. He is on warfarin for atrial fibrillation but has no other problems and no other medications. Slide 52 CASE 2 (2 of 3) What is the most appropriate next step in management? (A) Observation only (B) Annual chest radiography (C) Repeat PPD testing in 6 mo (D) Treatment with pyrazinamide plus rifampin for 2 mo (E) Treatment with isoniazid for 9 mo Slide 53 CASE 2 (3 of 3) What is the most appropriate next step in management? (A) Observation only (B) Annual chest radiography (C) Repeat PPD testing in 6 mo (D) Treatment with pyrazinamide plus rifampin for 2 mo (E) Treatment with isoniazid for 9 mo Slide 54 CASE 3 (1 of 3) • A 72-year-old man is seen for preoperative assessment in anticipation of a prostate biopsy. • He has asymptomatic aortic stenosis with a stable III/VI holosystolic murmur and type II diabetes mellitus controlled by diet. • He is allergic to penicillin but has taken cephalexin or clindamycin for dental procedures in the past without difficulty. Slide 55 CASE 3 (2 of 3) Which of the following is the most appropriate recommendation regarding endocarditis prophylaxis for the biopsy? (A) No prophylaxis (B) Oral cephalexin (C) Intravenous cefazolin (D) Oral cephalexin plus oral clindamycin (E) Intravenous cefazolin plus intravenous clindamycin Slide 56 CASE 3 (3 of 3) Which of the following is the most appropriate recommendation regarding endocarditis prophylaxis for the biopsy? (A) No prophylaxis (B) Oral cephalexin (C) Intravenous cefazolin (D) Oral cephalexin plus oral clindamycin (E) Intravenous cefazolin plus intravenous clindamycin Slide 57 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Editor: Annette Medina-Walpole, MD GRS7 Chapter Author and Question Writer: Kevin Paul High, MD, MSc Pharmacotherapy Editor: Judith L. Beizer, PharmD Medical Writers: Beverly A. Caley Faith Reidenbach Managing Editor: Andrea N. Sherman, MS Copyright 2010 American Geriatrics Society Slide 58