* Your assessment is very important for improving the work of artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download REGION II: Southeastern Minnesota

Great Lakes tectonic zone wikipedia , lookup

Post-glacial rebound wikipedia , lookup

Geomorphology wikipedia , lookup

Algoman orogeny wikipedia , lookup

Geology of Great Britain wikipedia , lookup

Sedimentary rock wikipedia , lookup

Clastic rock wikipedia , lookup

Marine geology of the Cape Peninsula and False Bay wikipedia , lookup

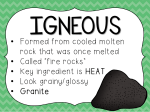

Southeastern Minnesota GEOLOGIC OVERVIEW Buried very deep under the surface of Southeastern Minnesota are ancient igneous rocks similar to the North Shore. On top of all these older rocks are several hundred feet of rock laid down in shallow seas about 600 million years ago. There is also some glacial debris brought in from other areas. The entire area has been eroded for the last 300 million years by wind, water and ice. Deep river valleys carved by glacial melt-water are the major surface features. These valleys easily show layers of rock that would normally be buried. Most of Minnesota has been covered by glacial ice several times in the last 15,000 years but one thing separates Southeastern Minnesota. The last ice age – the Wisconsin - did not cover Southeastern Minnesota. For this reason there is much less glacial sediment and more deeply carved river valleys compared to the rest of the state. When the climate began to warm up and the glaciers elsewhere began to melt, the glacial melt water flowed over this area and carved deep valleys. These deep river valleys show the history and evolution of life in Minnesota through fossils and layers of rock that are shown instead of being deeply buried. Surface water, wind and glaciers are not the only force that has shaped Southeastern Minnesota. Naturally acidic groundwater has slowly eroded bedrock and created incredible land features such as caves and sinkholes. These are the forces that have shaped this region. ROCKS Rock cycle processes in the past include deposition of sediment at the bottom of shallow seas and erosion and weathering by flowing glacial melt water. Rock cycle processes that are occurring today are normal weathering and erosion by precipitation, runoff, and rivers. In Southeast Minnesota there is also weathering and erosion of underground rocks from naturally acidic groundwater. Shale: During the Cambrian and Ordovician time periods, about 600 million years ago, most of Minnesota was covered by shallow seas. The oldest (and deepest) rocks are shale. The greenish-grayblack sedimentary rock was formed by mud-like clay particles falling out of ocean water making thin, flat layers on the bottom that hardened into rock. The greenish color is thought to be from the digestive processes of marine worms. Sandstone: Sand with iron and calcite minerals layered on the bottom of the ocean. They were pressed and cemented together to form this sedimentary rock. These sandstone layers range from white to yellow to red. The Jordan layer of sandstone holds a significant amount of groundwater and much of this area gets drinking water out of this sandstone. Dolomite: This gray sedimentary rock is dominated by the minerals calcium and magnesium. Dolomite is also formed as these minerals dropped out of ocean water in layers and cemented into a hard rock. Limestone: As the ocean water continued to deepen and quiet, calcium carbonate was deposited from the warm seawater and the shells of many marine animals. These materials were pressed and cemented together to form rock. Limestone in Southeastern Minnesota is a yellow-tan-gray sedimentary rock. FOSSILS: Marine animals were common in the shallow seas of Minnesota 500-600 million years ago. Marine fossils may be found in practically any sedimentary rock cut or quarry in Southeastern Minnesota. Park along a road cut (where you can see rock layers) and look at the ground in the ditch. Rainwaters continually wash fossils out of the soft rock into the ditches. The sedimentary rocks that you find fossils in formed on the bottom of an ocean, to touch a fossil is to go back in time. MAJOR FEATURES Driftless Area: Extreme Southeastern Minnesota has a rugged landscape of broad valleys and ridges. It was apparently never covered by glaciers (glaciated) or was glaciated so early that no evidence remains. Soft sandstone hills and spires (spikes) are common here but they are not found in the rest of Minnesota where glaciers eroded them. Large, old river valleys were deepened and widened from glacial melt waters but were never scoured or buried in glacial sediment. Why wasn’t this area glaciated? Highlands to the northeast and northwest deflected the southward flowing ice. The Root River Valley near Eagle Bluff Residential Environmental Learning Center will show you one of these wide river valleys that was carved by glacial melt water thousands of years ago, not the current Root River. The Root River is a post-glacial river. Karst Topography: Nine counties in Southeastern Minnesota have a karst landscape, including eastern Rice County. Karst is a landscape that develops in areas with limestone and dolomite at the surface that is dissolved by naturally acidic groundwater. Six features are dominant in karst regions. - Streams that disappear underground - Valleys with no streams - Caves - Springs - Sinkholes - Little flowing surface water Karst forms naturally when limestone is dissolved by slightly acidic water. Groundwater mixes with carbon dioxide to form a weak acid (carbonic acid). Carbon dioxide gas comes from the air and from bacteria decomposing in the soil. Below the water table, limestone is always in contact with the groundwater. This contact speeds up the dissolving of the rock. Cracks and holes are formed in the rock. Larger spaces are called passageways, caverns, or caves. If a cave roof falls in, the hole at the surface is called a sinkhole. Water moves fast in karst regions. In non-karst areas, water must pass slowly through pore spaces of rocks and soil, slowing the water down. Cracks and holes in karst rocks let water through easily. Pollutants can also get into the groundwater easily. Runoff from storms can become groundwater in hours or minutes. Sewage, fertilizers, oils, and other harmful materials can damage groundwater very quickly in karst regions. This pollution puts our greatest natural resource, groundwater used for drinking water, at severe risk.