* Your assessment is very important for improving the work of artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download in Elderly People

Remote ischemic conditioning wikipedia , lookup

Management of acute coronary syndrome wikipedia , lookup

Heart failure wikipedia , lookup

Cardiac contractility modulation wikipedia , lookup

Coronary artery disease wikipedia , lookup

Myocardial infarction wikipedia , lookup

Cardiac surgery wikipedia , lookup

Jatene procedure wikipedia , lookup

Electrocardiography wikipedia , lookup

Dextro-Transposition of the great arteries wikipedia , lookup

Quantium Medical Cardiac Output wikipedia , lookup

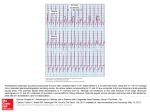

Significance of Chronic Sinus Bradyeardia in Elderly People By NEIL S. AGRUSS, M.D., ELAINE Y. RosIN, M.D., ROBERT J. ADOLPH, M.D., AND NOBLE 0. FOWLER, M.D. SUMMARY Downloaded from http://circ.ahajournals.org/ by guest on June 18, 2017 It may be difficult to evaluate sinus bradyeardia in the elderly since sinus rates below 50 beats/min may occur normally with aging. Seven asymptomatic bradyeardic subjects (heart rates 41-51 beats/min), ages 67-79 years, with no evidence of impaired cardiac performance and taking no drugs, were compared with four age-matched controls (heart rates 60-84 beats/min). Autonomic function was tested with the Valsalva maneuver, amyl nitrite inhalation, methoxamine infusion, head-up tilt, and atropine intravenously (2 mg). Cardiac index at rest was normal in bradyeardic subjects (2.4 0.1 SEM); increased cardiac stroke volume (SV) compensated for the slow heart rate. With supine bicycle exercise, increase in cardiac output per 100 ml increase in oxygen consumption was normal in bradyeardics (885 + 60 ml compared to 907 171 ml in controls). This exercise response was achieved mainly by increased SV in bradyeardics and by increased heart rate in controls. Significant increases in cardiac output occurred with both atropine and atrial pacing in bradyeardics, but not in controls. Autonomic impairment was not found. Increased vagal tone in bradyeardics was suggested by a lesser heart rate response to exercise and passive tilting. Hence, a heart rate below 50 beats/min in elderly people does not necessarily indicate depressed cardiac performance. Further evaluation of the significance of bradycardia in these subjects requires long-term observation. Additional Indexing Words: Heart rate Cardiac output Response to atrial pacing Response to atropine Autonomic function Exercise response RE'esponse to passive head-up tilt S INUS bradyeardia in the adult may be defined as a heart rate below 60 beats/ min with a normal sequence of cardiac activation. Recent reports have emphasized L chronic sinoatrial bradyeardia as a cause of From the Division of Cardiology, Department of Medicine, University of Cincinnati College of Medicine, Cincinnati General Hospital, Cincinnati, Ohio 45229. Supported in part by the National Institute of Health Grants HE-06307 and HE-5445, and the Heart Association of Southwestern Ohio. Address for reprints: Neil S. Agruss, M.D., Cardiac Research Laboratory, H/3, Cincinnati General Hospital, Cincinnati, Ohio 45229. Received: March 2, 1972; revision accepted for publication May 31, 1972. 924 cerebral dysfunction, syncope, and other symptoms of diminished cardiac output or regional blood flow.'-6 Most patients reported have been over 50-60 years of age, with resting heart rates near 40-50 beats/min. Associated cardiac rhythm and AV conduction disturbances have been frequent. Without these a decision as to whether or not sinus bradyeardia causes symptoms may be difficult, since dizziness, fatigue, weakness, exertional dyspnea and syncope can result from a variety of noncardiac disorders in the elderly, and the resting heart rate tends to diminish with age.7 This paper reports hemodynamic data obtained from seven elderly asymptomatic bradyeardic subjects during supine rest Circulation, Volume XLVI, November 1972 925 SINUS BRADYCARDIA IN THE ELDERLY Downloaded from http://circ.ahajournals.org/ by guest on June 18, 2017 supine bicycle exercise, and during sustained increase of the heart rate by atrial pacing. Autonomic nerve function was evaluated from the response of the heart rate and blood pressure to head-up tilt, Valsalva maneuver, amyl nitrite inhalation, intravenous methoxamine, and a 2.0 mg intravenous dose of atropine. The data were compared to those obtained from a group of age-matched con- and were averaged. No more than 2 min elapsed between duplicate cardiac output determinations. Systemic arterial and right atrial pressures were recorded on an Electronics-for-Medicine photographic recorder using Statham P23dB pressure transducers. Gauges were leveled 10 cm above the table top for all supine studies, and at the level of the midright atrium, as determined fluoroscopically, during head-up tilt. A bipolar electrode catheter* was used for pacing the right trols. Following placement of all catheters the resting cardiac output (CO), heart rate (1HR1), and brachial artery (BA) pressure were measured. The HR and BA pressure xvere then continuously recorded during the Valsalva maneuver,9 during inhalation of amyl nitrite, and following a 2-min intravenous infusion of methoxamine, 0.06 mg/ kg. The subject was then tilted head-up to a 450 angle with the horizontal. CO, HR, and BA pressure measurements were made after 3 min of tilt. Following return to the horizontal position and after a 10-min rest, the atrial rate was slowly increased by atrial pacing. After at least 5 min had elapsed at pacing rates of approximately 70 and 90 beats/min in the bradycardic subjects, and 90 beats/min in controls, the CO, HR, and BA pressure were measured. The atrial rate was then increased by 10 beats/min increments to 150 beats/min or until second degree AV block appeared. The postpacing recovery time of the sinus node pacemaker was observed following sudden cessation of the highest pacing rate attained. The subjects then exercised in the supine position on a bicycle ergometer, maintaining a work rate of 150 kg-meters/min (1200 ft lbs/min). This work level increased oxygen consumption two and a half to three times control. During the sixth and seventh min of exercise expired air was collected and CO, HR, and BA pressure were measured. After the subjects rested 15 min, the circulatory response to exercise at a controlled heart rate was measured in four of the seven bradyeardic subjects. The resting HR was increased by atrial pacing to rates slightly above those attained spontaneously dur- Methods The bradycardic subjects were seven men, ages 67-79 years, with resting heart rates between 41 and 51 beats/min. Each had chronic sinus bradyeardia as determined from two or more electrocardiograms recorded over a 6-month, or longer period of time. Additional electrocardiographic findings were: first degree AV block in two subjects (PR interval-0.24 sec in each); first degree AV block (PR interval 0.48 sec) and left anterior hemiblock in one subject; intermittent RBBB (unrelated to heart rate) in one subject; and possible left ventricular hypertrophy (voltage criteria only) in one subject. No subject at any time had electrocardiographic evidence of an atrial or ventricular tachyarrhythmia, SA block, sinus arrest, AV junctional rhythm, or second or third degree AV block. All seven subjects were asymptomatic and had no history of heart disease or hypertension; none was taking medication. No subject had athletic training or was engaged in a prescribed exercise program. Chest roentgenograms were normal in each subject, and none had clinical or laboratory evidence of impaired cardiac reserve, hypothyroidism, diabetes, chronic renal disease, neurologic disease, malignancy, hyperlipidemia, anemia, or electrolyte disturbance. Four healthy subjects, three men and one woman, ages 61-79 years, with resting heart rates between 60 and 84 beats/min, served as the control group. Each had normal electrocardiograms and chest X-rays; none was taking medication. Informed consent was obtained from all 11 subjects before the study. On the day before study each subject was acquainted with the equipment and procedures to be employed, and trained in the Valsalva maneuver. All subjects were studied in the postabsorptive state without receiving premedication. Cardiac outputs were measured by the dye-dilution technic (indocyanine green). Methods for determining heart rate, stroke volume, and oxygen consumption have been previously reported.8 Duplicate cardiac output determinations during rest, head-up tilt, exercise, various rates of atrial pacing, or following atropine agreed within 10% Circulation, Volume XLVI, November 1972 atrium. ing exercise; exercise was then performed as before. The CO, HR, and BA pressure were again measured during the seventh minute of exercise. Following a 15-min rest period, each subject received 2.0 mg of atropine intravenously in 2 min. Four minutes after the injection CO, HR, and BA pressures were again measured. Resting CO, HR, and BA pressure measurements were obtained in each subject before head-up tilt, *NBIH Catheter, U. S. Catheter & Corporation, Clens Falls, New York. Instrumiient AGRUSS ET AL. 926 before atrial pacing and exercise studies, and before atropine. Results Downloaded from http://circ.ahajournals.org/ by guest on June 18, 2017 Individual and group mean data for both the bradyeardic and control subjects are shown in the figures. The mean age and body surface area were similar in both groups. Right atrial pressure was normal and not significantly different in the two groups at rest and during subsequent interventions. Other than the HR and stroke index (SI), the resting baseline data for the two groups were similar (figs. 1 and 2). The mean heart rates of the two groups differed significantly (P< 0.001). There was no significant difference in mean resting cardiac index (fig. 1). Cardiac index (CI) was similar to that reported for normal subjects of similar age.7 10 The difference in SI between the groups was statistical- PACING CONTROLS BRADYCARDIGS 0@ 3.0 0 I, I ly significant (P < 0.001). Although there was no significant difference in the mean brachial artery pressure, the pulse pressure, as expected, was greater in the bradyeardic group. Oxygen consumption of the groups were similar (fig. 3), and both values were normal for the age of the subjects.7 10 Atrial pacing was successful in significantly increasing the HR in six of seven bradyeardic subjects. One (C.S.) developed second-degree AV block at a paced rate of 52 beats/min. The difference in mean paced HR between the groups was not significant. Atrial pacing significantly increased the CI of the bradyeardic group, but not in the controls (fig. 1). The mean paced CI in bradyeardic subjects was not significantly different from that of the control group. The response of the HR, CI, and SI to muscular exercise is summarized in figure 2. The CI rose to similar levels in the two groups. Although the differences between the groups for HR and SI were not statistically significant, the bradyeardic subjects tended to achieve a higher stroke output and lower HR during exercise than did the control subjects, findings similar to those at rest. Oxygen consumption increased comparably in both T I* 0 l 0, -3 ' 80 Ge 70- -9 2.5 60 8 50 7 I1 2t. 1..0 0 40 2.0 -- 30 -4 N~~~~~~~~~H ( ET4,MI 72±5 88±1 (60-84) (86-90) Beats/Minute 45±2 83±4 (41- 51) (69-91) Figure 1 CI values at rest and during atrial pacing are shown ). for each control and bradycardic subject ( The mean values are shown by (o) and SEM by vertical bars. The mean resting HR of the control subjects was 72 + 5 beats/min (range: 60-84); the mean HR during atrial pacing was 88 ±+1 beats/min (range: 86-90). The mean resting HR of the bradycardic group was 45 + 2 beats/min (range: 41-51); the mean HR during pacing was 83 + 4 beats/mmn (range: 69-91). Theresponse of the HR, Sl nd CI to muscular3 20~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~ ---- 40 80 60 100 120 ( 0 HR (BEATS/MIN) ____&d.ycardics Figure 2 The response of the HR, Si, and CI to muscular exercise is shown in the control (.--- -e) and brady- cardic (.---*) subjects. The SI is plotted on the ordinate and the HR on the abscissa; the isopleths represent levels of CI. The closed circle to the left of each connected pair represents resting values and the closed circle to the right represents exercise values. Circulation, Volume XLVI, November 1972 SINUS BRADYCARDIA IN THE ELDERLY 927 13 11 9 7 5 Downloaded from http://circ.ahajournals.org/ by guest on June 18, 2017 *- 3 *Bradycardic x-x 200 600 400 Control 800 1000 (cc /minute) vo2 Figure 3 The relationship between CO and oxygen consumption (VQ2) at rest and during exercise is ) subjects. The symbols (. or x) shown for the control (X X) and bradycardic ( on the left represent resting values and those on the right, exercise values. (The slope of each line is a function of the exercise factor.) groups during exercise. In addition, the increases in CO per 100 ml increase in oxygen consumption (exercise factor) were similar (fig. 3). The bradycardic group had an exercise factor of 907 171 ml/ 100 ml and the 60 ml/ 100 ml. The exercise factors compare closely to those found by Granath and associates10 in a group of normal elderly individuals. Figure 3 shows the relation of oxygen consumption to cardiac control group, 885 + output for all subjects. The ability of the heart to increase stroke volume during exercise while maintaining the HR constant, at a rate just above that achieved during the previous exercise period, was evaluated in four bradycardic subjects. As figure 4 shows, the increase in CI for each of the subjects was similar to that during the Circulation, Volume XLVI, November 1972 preceding exercise period, when HR was not controlled, and resulted almost entirely from an increase in stroke volume. With 2.0 mg atropine intravenously, HR increased significantly in both groups of subjects (fig. 5). The bradycardic subjects had a significantly greater absolute and percentage increase in HR than did the controls (P < 0.05). Bradycardic subjects tended to have a more limited HR response during exercise than to atropine when compared to the control subjects. Following atropine mean CI did not differ significantly between the two groups (fig. 5). A statistically significant increase in mean CI was found in the bradycardic group (P < 0.001). The difference between the mean resting CI and postatropine CI in the control group was not significant. 928 AGRUSS ET AL. 8Or <-Cs~~~~~~~~~~'I \ 70 -\\ *\ £EAelcise -Pace 60 ATROPINE Eae,c,se , S\\ -5 - - X s W,W, H. 40 -1 FH -_ *9 B.G. c'9 6 11 5 -..J 3.0 n _I 30f_ 4 Rest-Pace BRADYCARDICS 8 7 50 CONTROLS 9 3 20 2 IV' 60 80 '- 100 120 140 HR (BEATS /MIN) Figure 4 6. Downloaded from http://circ.ahajournals.org/ by guest on June 18, 2017 lines connecting the solid circles show the change from rest to rest-pace. The atrioventricular conduction system was stressed by atrial pacing. Four bradyeardic subjects developed second-degree AV block at paced rates of 105 beats/min or less (105, 100, 91 and 52 beats/min, respectively). The lowest rate at which AV block occurred in the control subjects was 107 beats/min. Following sudden cessation of pacing, at the highest rate attainable, spontaneous sinoatrial activity returned within 1.1 sec (range 0.6-1.1) in each subject. AV junctional rhythm was not seen in any subject following the administration of atropine. Blood pressure responded normally9' 11 during the Valsalva maneuver in all control and bradyeardic subjects. All individuals showed a narrowing of the pulse pressure during phase II and an overshoot of the BP during phase IV. The average percentage increase in HR during the strain (phase II) was similar in both groups: 27% for controls and 26% for bradycardic subjects. Slowing of the HR occurred during phase IV in all subjects, but in the bradyeardic group the rate usually did not decrease below the control HR. Following amyl nitrite inhalation or intravenous meth- 2.5 '311 At the left of the figure the relationship of HR, SI, and CI is shown in four bradycardic subjects at rest and during exercise. To the right are plotted the HR, SI, and CI for these same four subjects during atrial pacing, while at rest (Rest-Pace) and while exercising (Exercise-Pace). The solid lines connecting the solid circles show the change from rest to exercise, and from rest-pace to rest-exercise. The straight dashed 2.0 72±5 108±12 (60-84) (90-143) 45±2 91±4 (41-51) (70-101) Beats/ Minute Figure 5 Cl values at rest and after intravenous administration of atropine are shown for each control and bradycardic subject. (*). The mean values are shown by (o) and SEM by vertical bars. The mean resting and postatropine heart rates for each group are shown the bottom of the figure. The range of HR is at shown in parentheses. no significant difference in per cent of HR change existed between the groups. Figure 6 shows the response of the HR to head-up tilt in both groups of subjects. The control subjects had a significantly greater percentage increase in HR during tilt (24%) than did the bradyeardic subjects (11%). The CI decreased to similar levels in both groups during tilt. In neither group did the mean BA pressure change significantly. oxamine Discussion It is known that the resting HR and CO tend to diminish with age,7 but data relating to the cardiac performance of asymptomatic elderly patients with resting heart rates of 40-50 beats/min are lacking. We therefore studied seven asymptomatic elderly subjects with sinus bradycardia and compared their cardiac performance with that of a group of Circulation, Volume XLVI, November 1972 SINUS BRADYCARDIA IN THE ELDERLY TILT 100 r 90 80 F -1.1 qll.14 -1. c 70 t q) 11. 60 50 Downloaded from http://circ.ahajournals.org/ by guest on June 18, 2017 40 30 Supine Tilt Figure 6 The HR at rest and during head-up tilt is shown for each control (---a-) and bradycardic ( ) subject. The means at rest and during tilt are shown by (o) and SEM by vertical bars, and are connected by the heavy line. age-matched control subjects. Although we found bradyeardic subjects to differ from normal in several respects, they had normal cardiac performance at rest and during exercise, and had no evidence of autonomic nervous system dysfunction. Although both groups achieved similar levels of CO during exercise the bradyeardics tended to do so by means of a higher stroke output and lower HR. This is similar to the resting hemodynamic pattern of the bradyeardics wherein they maintained a normal CO by an increased stroke output. With the HR held constant during exercise in four of the bradyeardic subjects it was found that levels of CO could be achieved that were similar to those attained when the HR was allowed to change. This ability to vary left ventricular stroke output in order to maintain a normal CO during stress tends to be lacking in patients with chronic heart disease.'2 Following the administration of atropine, bradyeardic subjects had a much greater Circulation, Volume XLVI, November 1972 929 absolute and percentage increase in HR. This would suggest that increased vagal tone13 was an important factor in the slow heart rates in the bradyeardic subjects. It is possible that had the exercise stress been greater the bradycardic subjects would have achieved heart rates similar to the controls, since withdrawal of vagal tone accounts in part for the increase in HR during exercise.14 Most studies 15, 16 have shown no signfficant change in CO with either atrial pacing or atropine in normal subjects. Despite apparently normal cardiac function in all subjects, we found that CO increased significantly only in bradyeardic subjects when HR was increased by atrial pacing or atropine. The explanation for this finding is not clear. It would be of interest to study the CO response to these interventions in bradyeardic athletes. Several significant similarities existed between the bradyeardic and control groups. The resting and exercise cardiac outputs of the two groups were similar. Both groups of subjects had similar increases in CO per 100 ml increase in oxygen consumption, the exercise factor. The resting cardiac outputs were normal for the age of the subjects.7 The exercise cardiac outputs and exercise factors were in agreement with the values that Granath and his associates found in a group of similarly aged normal men performing supine bicycle exercise.10 It is thus concluded that normal cardiac performance was present in our group of bradyeardic subjects. By the tests described in this study, no evidence of autonomic nervous system dysfunction was found in any subject. The normal responses of the BP and HR to the Valsalva maneuver and of the HR to manipulation of the BP suggests that an intact baroreceptor reflex arc was present and that sympathetic and parasympathetic pathways were also intact.17 In addition, none of the bradyeardic subjects had clinical evidence of generalized dysfunction of the sympathetic nervous system, e.g. orthostatic hypotension, diminished sweating, or pupillary changes. Although all subjects had an increase in HR during headup tilt, the response of the HR in the 930 AGRUSS ET AL. bradyeardic subjects was significantly less than that of the control subjects. A diminished increase in HR during head-up tilt can be seen in patients who are in congestive heart failure."' 19 However, none of the bradycardic subjects had any evidence of impaired cardiac performance. It is possible that an increased level of vagal tone accounted for the blunted HR response to tilt in the bradyeardic subjects. Downloaded from http://circ.ahajournals.org/ by guest on June 18, 2017 Although a significant number of our bradycardic subjects had evidence of impaired AV conduction, this was the only evidence suggestive of cardiac disease. Unlike the findings in patients with so called "sick sinus node" disease, serial electrocardiograms showed normal sinus node activity, the recovery time of sinoatrial discharge following atrial pacing was normal, and our studies showed normal left ventricular performance. Because of the patient's age, however, coronary artery disease or degenerative disease in the SA node or atrial muscle must be considered. Only by long term followup of these asymptomatic bradyeardic subjects will we learn whether their bradycardia will remain benign. There is a need for comparable studies in a symptomatic group of subjects with sinus bradyeardia, especially with regard to the effects of atrial pacing, exercise and atropine. As shown in this report, significant degrees of sinus bradyeardia may be associated with aging. In this latter setting, increased vagal tone may be a significant contributing factor to the bradyeardia, and more importantly, normal cardiac performance can be present. Therefore, the implications and management of sinus bradycardia depend upon the setting in which it occurs. 3. RASMUSSEN K: Chronic sinoatrial heart block. Amer Heart J 81: 38, 1971 4. FERRER MI: The sick sinus syndrome in atrial disease. JAMA 206: 645, 1968 5. SCHUILMAN CL, RUBENSTEIN JJ, YURCHAK PM, DESANCTIs RW: The `sick sinus" syndrome: Clinical spectrum. (Abstr) Circulation 42 (suppl III): III-42, 1970 6. FRUEHAN CT, OBEID AI, SMULYAN H, EIcH RH: Sick sinus syndrome: One year's experience. (Abstr) Circulation 42 (suppl III): III-154, 1970 7. BRANDFONBREN-ER M, LANDOWNE M, SHOCK NW: Changes in cardiac output with age. Circulation 12: 557, 1955 8. ADOLPH RJ, HOLMES JC, FUKUSUMI H: Hemodynamic studies in patients with chronically implanted pacemakers. Amer Heart J 76: 829, 1968 9. GoRLIN R, KNOWLES JH, STOREY CF: The 10. 11. 12. 13. 14. 15. 16. 17. References 1. FOWLER NO, FENTrON JC, CONWAY GF: Syncope and cerebral dysfunction caused by bradyeardia without atrioventricular block. Amer Heart J 80: 303, 1970 2. WALTER PF, REID SD JR, WENGER NK: Transient cerebral ischemia due to arrhythmia. Ann Intern Med 72: 471, 1970 18. 19. Valsalva maneuver as a test of cardiac function. Amer J Med 22: 197, 1957 GRANATH A, JONSSON B, STRANDELL T: Circulation in healthy old men, studied by right heart catheterization at rest and during exercise in supine and sitting position. Acta Med Scand 176: 425, 1964 STONE DJ, LYON AF, TEIRSTEIN AS: A reappraisal of the circulatory effects of the Valsalva maneuver. Amer J Med 39: 923, 1965 BICKELMANN AG, LIPPSCHurz EJ, WEINSTEIN L: The response of the normal and abnormal heart to exercise. Circulation 28: 238, 1963 CHAMBERLAIN DA, TURNER P, SNEDDON JM: Effects of atropine on heart rate in healthy men. Lancet 2: 12, 1967 ROBINSON BF, EPSTELN SE, BEISER GD, BRAUNWALD E: Control of heart rate by the autonomic nervous system. Circ Res 19: 400, 1966 Ross J JR, LINHART JW, BRAUNWALD E: Effects of changing heart rate in man by electrical stimulation of the right atrium. Circulation 32: 549, 1965 KosowsKY BD, STEIN E, LAU SH, LISTER JW, HAF-1 JI, DAMIATO AN: A comparison of the hemodynamic effects of tachycardia produced by atrial pacing and atropine. Amer Heart J 72: 594, 1966 THOMSON PD, MELMON KL: Clinical assessment of autonomic function. Anesthesiology 29: 724, 1968 HICKLER RB, HOSKINS RG, HAMLIN JT III: The clinical evaluation of faulty orthostatis mechanisms. Med Clin Amer 44: 1237, 1960 ABELMANN WH, FAREEDUDDIN K: Increased tolerance of orthostatic stress in patients with heart disease. Amer J Cardiol 23: 354, 1969 Circulation, Volume XLVI, November 1972 Significance of Chronic Sinus Bradycardia in Elderly People NEIL S. AGRUSS, ELAINE Y. ROSIN, ROBERT J. ADOLPH and NOBLE O. FOWLER Downloaded from http://circ.ahajournals.org/ by guest on June 18, 2017 Circulation. 1972;46:924-930 doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.46.5.924 Circulation is published by the American Heart Association, 7272 Greenville Avenue, Dallas, TX 75231 Copyright © 1972 American Heart Association, Inc. All rights reserved. Print ISSN: 0009-7322. Online ISSN: 1524-4539 The online version of this article, along with updated information and services, is located on the World Wide Web at: http://circ.ahajournals.org/content/46/5/924 Permissions: Requests for permissions to reproduce figures, tables, or portions of articles originally published in Circulation can be obtained via RightsLink, a service of the Copyright Clearance Center, not the Editorial Office. Once the online version of the published article for which permission is being requested is located, click Request Permissions in the middle column of the Web page under Services. Further information about this process is available in the Permissions and Rights Question and Answer document. Reprints: Information about reprints can be found online at: http://www.lww.com/reprints Subscriptions: Information about subscribing to Circulation is online at: http://circ.ahajournals.org//subscriptions/