* Your assessment is very important for improving the work of artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download Original papers QJM

Survey

Document related concepts

Transcript

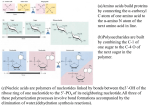

Q J Med 1999; 92:495–503 Original papers QJM Hyperphenylalaninaemia in children with falciparum malaria C.O. ENWONWU1,2 B.M. AFOLABI3, L.A. SALAKO3, E.O. IDIGBE3, H. AL-HASSAN4 and R.A. RABIU5 From the Departments of 1OCBS, School of Dentistry, and 2Biochemistry, School of Medicine, University of Maryland, Baltimore, Maryland, USA, 3Nigerian Institute of Medical Research, Lagos, 4Specialist Hospital, Sokoto, and 5Massey Street Children Hospital, Lagos, Nigeria Received 5 February 1999 and in revised form 5 July 1999 Summary Brain monoamine levels may underlie aspects of the cerebral component of falciparum malaria. Since circulating amino acids are the precursors for brain monoamine synthesis, we measured them in malaria patients and controls. Malaria elicited significantly elevated plasma levels of phenylalanine, particularly in comatose patients, with the Tyr/Phe (%) ratio reduced from 83.3 in controls to 39.5 in infected children, suggesting an impaired phenylalanine hydroxylase enzyme system in malaria infection. Malaria significantly increased the apparent K for m Trp, Tyr and His, with no effect on K for Phe. m(app) Using the kinetic parameters of NAA transport at the human blood–brain barrier, malaria significantly altered brain uptake of Phe (+96%), Trp (−28%) and His (+31%), with no effect on Tyr (−8%), compared with control findings. Our data suggest impaired cerebral synthesis of serotonin, dopamine and norepinephrine, and enhanced production of histamine, in children with severe falciparum malaria. Introduction Malaria is a major cause of morbidity and mortality in sub-Saharan Africa, and kills more than one million children annually.1,2 The factors that determine whether a child develops mild or severe malaria are numerous and complex.1 Severe Plasmodium falciparum malaria is a multisystem disease involving several metabolic disturbances and endocrine dysfunctions,1,2 with recurrent paroxysms of high fever, persistent vomiting, confusion, seizures, and loss of consciousness (cerebral malaria) among the danger signs.2–5 Resting energy expenditure may be increased by as much as 30%.3 The fever elicits several host responses, such as altered fat and carbohydrate metabolism, increased catabolism of skeletal muscle, complex alterations in the metabol- ism of individual amino acids, and enhanced nitrogen excretion, with changes in the priority for protein synthesis, and increased gluconeogenesis, among others.2,6,7 The host’s responses, especially those mediated through cytokine cascade, may determine disease severity.8,9 The cytokines stimulate release of glucocorticoids which in turn inhibit cytokine gene expression, in addition to promoting catabolism of muscle proteins and increased mobilization of amino acids to the liver.9–11 Abnormalities of hepatic2,12 and renal13 functions are seen in a significant proportion of children with severe malaria. Plasmodium falciparum infection is considered one of the commonest causes of acute encephalopathies in children residing in falciparum-malaria- Address correspondence to Professor C.O. Enwonwu, Departments of Biochemistry and OCBS, Schools of Medicine and Dentistry, 666 West Baltimore Street, Room 4G31, Baltimore, MD 21201-1586, USA © Association of Physicians 1999 496 C.O. Enwonwu et al. infected countries.2,14 There is good evidence that some common disorders of central monoamine metabolism may underlie the pathogenesis of metabolic encephalopathies.15,16 Studies in mice and rats with Plasmodium berghei infection indicate significantly reduced whole brain contents of 5-hydroxytryptamine (serotonin) and norepinephrine, while levels of dopamine and histamine remain unaltered.17 Large neutral amino acids circulating in blood plasma are precursors for the synthesis in brain of the monoamines, as well as other putative neurotransmitters such as carnosine, and important cofactors such as S-adenosyl-methionine,18 and alterations in their concentrations or turnover in the brain could affect monoaminergic functions.19 This latter idea derives from reports that the rate-limiting steps in cerebral biosyntheses of these neurotransmitters are not saturated by normal concentrations of the relevant precursor amino acids in brain cells, and that, therefore, amino acid transport at the blood–brain barrier (BBB) plays a critical role in the overall regulation.18 Studies of changes in the free amino acid (AA) plasma pool in malaria are limited, contradictory, and based mainly on the avian malaria Plasmodium lophurae in ducklings,20,21 with the animals demonstrating selective increases in plasma concentrations of specific amino acids.21 Since the brain is uniquely vulnerable to plasma hyperaminoacidaemia,18 our study was designed to examine the changes in plasma free amino acids in African children with P. falciparum malaria. We also evaluated plasma levels of free cortisol and ascorbate, as additional indices of the metabolic consequences of the disease. Methods Approval for this study was by the Ethical Committees of the Nigerian Institute of Medical Research, Yaba, Lagos, the Lagos State Health Management Board, and the Ministry of Health, Sokoto State. Informed consent was obtained from the accompanying parents or guardians of the patients, who were assured of the confidentiality of individual results. Study areas and patients The studies were carried out at the Massey Street Children’s Hospital, Lagos, and the Sokoto Specialist Hospital, Sokoto City, Sokoto State. Both hospitals are located in very high-density areas with deplorable environmental sanitation, and grossly inadequate basic amenities such as potable water as well as an unreliable electricity supply. The former hospital draws its patients from a population of about 2 million people residing in the Lagos metropolis, while Sokoto Specialist Hospital draws its patients not only from Sokoto State, but also from the two neighbouring states of Kebbi and Zamfara. As in most states in Nigeria, malaria is endemic in the study areas, especially during the rainy season, with Plasmodium falciparum predominating. We recruited 28 randomly-selected children (13 females and 15 males, ages 14–156 months, mean±SD age 65.14±49.05) from the lowsocioeconomic urban communities in Sokoto and Lagos. These children, 13 from Sokoto and the rest from Lagos, were selected from a much larger group of patients who presented at the hospitals during a 3-week period in 1997, with fever of varying degrees ranging from 38.0 to 40.8 °C. The children recruited from the two hospitals showed no significant difference in mean weights for age Z-scores and were, therefore, treated as one single group for the purposes of the study. Most of the children complained of persistent fever of a few days duration, with loss of appetite, nausea, vomiting and headache. Exclusion criteria were presence of a chronic illness, congenital abnormalities, other overt infectious diseases, severe malnutrition as exemplified clinically by kwashiorkor or marasmus, and food consumption within 6 h prior to presentation at the hospital. Each patient was given a full clinical examination. In particular, presence of jaundice, pallor, hepatomegaly and spleen enlargement were carefully documented. Four of the patients presented at the hospital with severelyimpaired consciousness, absent corneal reflexes, repeated convulsions of the whole body, poor motor response to noxious stimuli, evidence of respiratory distress, and other features associated with cerebral malaria.22 The depth of coma was not measured. For comparative purposes, 28 children (mean age 72.1±18.8 months), distributed equally between genders and without malaria and overt signs of other infections, were recruited as the control group. These control children (14 each from Lagos and Sokoto) resided in the same low-socioeconomic-status urban communities as the children with malaria. They were enrolled in the study when they visited the hospitals (out-patient clinics) and the primary health-care centres for routine immunizations and a countrywide oral health screening program. The control children were recruited into the study during the same time interval as the malaria-infected children, and like the latter, they were predominantly of Hausa, Fulani, and Yoruba ethnic origins. Clinical methods Axillary temperature was measured with a mercury thermometer, using 1 min stabilization time. Pyrexia was defined as any temperature of 37.5 °C and above. Finger prick blood was obtained from each malaria patient for examination for malaria parasites 497 Hyperphenylalaninaemia in malaria and determination of packed cell volume (PCV). Thick and thin blood films were prepared on the same slide for each child. The slide was stained using buffered Giemsa23, and examined under oil immersion at ×700 magnification. Laboratory diagnosis of malaria was based on observation of any stage of development of malaria parasites within the red blood cells. Species of the parasite was determined from the thin film. Parasite density was determined as previously described,23 using the thick film preparation. Four hundred fields were examined and certified to contain no parasites before a slide was declared negative. Anthropometry Body weight of each child was measured to the nearest 0.1 kg using a scale whose precision was frequently checked. Height was measured to the nearest mm. Assessment of nutritional status was predicated on weight-for-height as an index of current nutritional state, and on height-for-age (stunting) as an index of past nutrition. Using computer programs developed by the WHO, Geneva, and the CDC, Atlanta, for nutritional anthropometry (Epi Info version 5.0 lb, 1993), weight-for-age, height-for-age, and weight-for-height Z-scores were calculated, and interpreted relative to the standard values of the National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS) published by the US Department of Health, Education and Welfare.24 The Z-score cutoff point chosen was −2 standard deviations from the reference median. Biochemical studies Sample collection Venous blood was collected at 09:00–11:00 h into heparinized tubes following fasting periods that lasted 6–12 h for the various subjects. At this stage, one male patient with malaria was excluded from the group because of inadequate blood collection. The blood-filled vacutainer tubes were retained in an ice-cooled chest until centrifuged (2000 g for 10 min) usually within 30 min after collection. The separated plasma was divided into aliquots for storage at −70 °C until analyzed. The aliquot for cortisol assay was stored in a siliconized tube. The aliquot for ascorbate assay was stabilized with an equal volume of freshly prepared 10% metaphosphoric acid before storage. Assays Levels of free amino acids in plasma were measured by reverse-phase HPLC following pre-column derivatization with phenylisothiocyanate.25 Phenylalanine shares the same transporter at the blood brain barrier (BBB) with valine, methionine, isoleucine, leucine, tyrosine, tryptophane and histidine, and all these amino acids possess different affinities for the transport site.26 To calculate brain uptake of these amino acids, the following equations26,27 were used: A B [AA] K =K 1+S m(app) m K (AA) m [AA].v max = +[AA]. K d [AA]+K m(app) where K is the apparent or normalized Km for m(app) amino acid (e.g. Phe), K is the measured K for m m that amino acid, [AA]/K (AA) is the concentration m divided by the measured Km for all other amino acids which share that transporter (e.g. Tyr, Trp, Ile, Leu, Met, Val, His), v is brain uptake for that amino acid, v is the measured v for that amino acid, max max [AA] is the plasma concentration of that amino acid, and K is the measured passive diffusion constant. d Values for K , v , and K for the large neutral m max d amino acids (LNAA) at human brain capillaries have been reported by Hargreaves and Pardridge.27 Determination of cortisol concentration in plasma was carried out with the ‘Gamma Coat’ 125IRadioimmunoassay Kit (Incstar), as previously described.28 The kit contained test tubes coated with rabbit anti-cortisol serum, 125I-labelled cortisol in phosphate-buffered saline, ANS (8-anilino1-naphthalene sulphonic acid) with 0.02 M sodium azide preservative, cortisol serum blank (cortisol-free processed human serum), phosphate-buffered saline, and cortisol standards in processed human serum in concentrations of 0, 1, 3, 10, 25 and 60 mg/dl (0, 28, 83, 276, 690 and 1655 nmol/l). Using unextracted plasma (10 ml), cortisol concentrations were determined as indicated in the instruction manual that came with the kit. Precision was checked using recovery from spiked, pooled serum samples, and was in the range of 93–102%. The reference ranges for plasma cortisol levels were 193–690 nmol/l (mornings) and 55–248 nmol/l (evenings). Plasma concentration of total ascorbic acid (dihydro-plus-dehydro-forms) was determined following derivatization with 2,4-dinitrophenylhydrazine as previously described.29 For interpretation of the data, we considered values <11 mmol/l to signify frank deficiency, values between 11 and 23 mmol/l as marginal or moderate risk of developing clinical deficiency signs, and values >23 mmol/l as normal.30 Statistical analysis Results were expressed as means±SD. Statistical differences between means were evaluated by using Student’s t-test when comparing groups, or by an analysis of variance of repeated measurements when 498 C.O. Enwonwu et al. comparing more than two situations. Differences between proportions were analyzed using x2 test. The level of significance was chosen as p<0.05. Results With the exception of four children who were comatose, the rest were alert on admission. The main presenting symptoms in the 27 patients included loss of appetite (96%), vomiting (70%), convulsions (30%), headache (22%), diarrhoea (26%), fever (100%), splenomegaly (10%) and hepatomegaly (24%). Pre-medication with analgesics (62%), chloroquine (41%), antihistaminics (11%), or multivitamins including folate (33%) was noted in some of the patients. The packed cell volume (PCV) in the sick children varied from 15% to 51%, with 23% of them having a PCV of less than 30%. Similarly, marked variability was noted in malaria parasite density among the patients (range 22–386 076/ml, with geometric mean parasite density of 2669/ml). The percentages of the patients who were underweight, stunted or wasted, as indicated by their weight-for-age (WAZ), height-for-age (HAZ), and weight-for-height (WHZ) Z-scores were 30.8, 17.4, and 20.0, respectively, an observation suggestive of protein-energy malnutrition (PEM) in a good number of the children.31 The most prominent changes in the plasma free amino acid profiles in the children with malaria in comparison to the non-infected children were significant ( p<0.05) increases in phenylalanine and histidine, and a decrease in arginine levels (Table 1). Non-significant alterations between the two groups were observed in the levels of most of the dietary essential and non-essential amino acids. The ratio (%) of Tyr/Phe decreased markedly from 83.3 in the non-infected children to 39.5 in the malaria group. The sum (SNAA) of the large neutral amino acids, including histidine (Val, Met, Ile, Leu, Phe, Trp, Tyr, His) which share the same transporter at the BBB, increased by 32% in the malaria group compared with the level in the non-infected group. Phenylalanine accounted for a good proportion of the increase in the children with malaria. For initial semi-quantitative evaluation of the potential effects of changing plasma amino acid concentrations on brain availability of each individual large neutral amino acid, we calculated the amino acid ratio,32 an approach that incorrectly assumed that all the large neutral amino acids have the same affinity for the BBB transporter.18,26,27 Nonetheless, the crude assessment indicated significantly increased Phe ratio (Phe/SNAA)% from 12.2 in the non-infected group to 24.7 in the malaria group (Table 1). The His and Trp ratios were significantly altered in the malaria group, but the Tyr ratio was unaffected. Using the K (apparent) for each amino acid,26,27 and published m kinetic parameters of transport (K , V and K ) for m max d the NAA at the human BBB,27 we derived more accurate data on the brain uptake of the various amino acids. As shown in Table 2, the apparent K m for Phe was not altered in the malaria group. In contrast, the infection produced a 25% significant increase in apparent K in each of Trp, Tyr, and His m compared with values for the control children. Malaria infection elicited significant increases in brain uptake of Phe (+96%) and His (+31%), a reduction in uptake of Trp (−28%), and no change in Tyr uptake, compared with findings in the control group (Table 2). The patients with malaria were further classified into three sub-groups of those who were comatose, those with parasite density in excess of 13 000/ml, and patients pre-medicated with folate before presentation at the study site. Excluded from the second sub-group were children in coma or those pre-medicated with folate. As shown in Table 3, the four patients in coma showed the highest degree of hyperphenylalaninaemia, which was not markedly different from the level in patients with high parasite density, but significantly higher (+86%) than the level observed in nine children with a history of premedication with folate. As summarized in Table 4, the malaria patients demonstrated prominently increased plasma free cortisol concentrations, with marked reductions in mean plasma total ascorbate levels compared to findings in the non-infected control children. Only 4 of the 27 patients (15%) had plasma ascorbate level within the normal range, while the rest had levels <23 mmol/l. Discussion Plasmodium falciparum is considered one of the commonest causes of acute encephalopathies in children in most endemic countries.1,4,14 Since disorders of central monoamine metabolism may underlie the pathogenesis of metabolic encephalopathies,16,18 the present studies focused primarily on circulating plasma levels of the large neutral amino acids, many of which serve as precursors for synthesis in brain of the monoamines (serotonin, dopamine, noradrenaline, and histamine).18,19,26,33 As shown in Table 1, increased plasma Phe was the most conspicuous change in the children with malaria, with Phe levels 2–3-fold those seen in uninfected children, and within the range of values reportedly characteristic of some individuals heterozygous for phenylketonuria.34 Our findings were consistent with reports showing plasma Phe concentrations 45–86% above 499 Hyperphenylalaninaemia in malaria Table 1 Plasma amino acid levels (mmol/l) Amino acids Malaria group (n=24)* Controls (n=26)* Threonine Valine Methionine Isoleucine Leucine Phenylalanine Tryptophane Lysine Histidine Arginine Tyrosine Glutamic acid Serine Asparagine Glycine Taurine Alanine SNAA Tyr/Phe(%) Phe/SNAA (%) Trp/(SNAA (%)) Tyr/SNAA (%) His/SNAA (%) SEAA SNEA SEAA/SNEA (%) 91.46±29.96 200.52±55.70 27.56±7.46 50.60±9.05 140.48±45.50 155.11±23.79a 38.90±7.11 156.46±42.11 108.77±20.26a 85.25±23.43a 61.30±14.86 268.28±90.30 171.98±53.18 58.47±9.52 257.99±78.35 116.27±39.63 378.53±60.09 783.24 39.52 24.69 5.23 8.49 16.13 1055.11 1312.82 80.37 102.11±18.20 188.08±26.55 25.13±5.65 52.62±11.05 96.55±21.77 64.52±8.08** 44.30±10.11 118.68±22.14 68.79±12.99** 123.10±18.77** 53.72±11.18 188.62±25.56 165.30±25.57 69.82±11.88 331.67±69.97 146.13±44.21 390.27±41.77 593.71 83.26** 12.19** 8.06** 9.95 13.10** 883.88 1345.53 65.69 Data are means±SD. SNAA, sum of large neutral amino acids (Val, Met, Ile, Leu, Phe, Trp, Tyr, His); SEAA, sum of essential amino acids (includes Arg, His); SNEA, sum of non-essential amino acids. * Three and two haemolysed samples discarded from malaria and control groups, respectively. ** Significantly different ( p<0.005 or 0.05) from same entry in other group. Table 2 Apparent K and calculated brain uptake of amino acids m Amino acid Phenylalanine Tryptophan Tyrosine Histidine Apparent K (mM) m Uptake (v) (pmol/min) Controls Malaria group Controls Malaria group 0.34±0.03 4.04±0.12 1.71±0.06 6.86±0.11 0.35±0.08 5.03±0.07 2.13±0.02 8.50±0.14 1.02 0.20 0.36 0.43 2.00 0.14 0.33 0.56 (+2.3%) (+24.5%)* (+24.7%)* (+23.9%)* (+96.1%)* (−28.2%)* (−8.3%) (+30.7%)* Data (means±SD) based on findings in 24 children in each group of children. Values in parentheses represent percent change from control value. * Significantly different (p<0.05) from corresponding control value. normal, in ducklings infected with Plasmodium lophurae.20,21 Factors predisposing to hyperphenylalaninemia include glucocorticoid-mediated catabolism of skeletal muscles in infections with increased release of Phe, PKU heterozygosity, hepatic disease and renal pathology with release of putative uraemic toxins that may affect phenylalanine hydroxylase, among others.7,18,35 Some of these factors, particularly impaired liver function2,36 and hypercortisolaemia,10 as indicated in Table 4, are frequent features of severe falciparum malaria in children. The pathological consequences of hyperphenylalaninemia are mainly in the brain,37,38 and may include such features as mental retardation, spasticity, and seizures.18 Indeed, a tripling of plasma Phe level to about 200 mM, as observed in the present study (Tables 1 and 3), may cause seizures, mood changes, insomnia, nausea, abdominal pain and diarrhoea,18,26 which are among the features commonly 500 C.O. Enwonwu et al. Table 3 Plasma phenylalanine and tyrosine in subgroups of malaria patients Subgroup Amino acid (mmol/l) Comatose patients (n=4) Parasite density >13 000 per ml (n=6)** Folate-treated (n=9)*** Phenylalanine Tyrosine Tyr/Phe (%) 241.93±46.34* 201.65±55.78 129.93±41.08* 77.88±26.78* 78.67±29.75 54.90±14.55* 32.3* 39.0 42.3* * Subgroups significantly different from each other ( p<0.05). ** Comatose children as well as those treated with folate were excluded from this sub-group. *** Sub-group did not include any comatose child. Table 4 Plasma cortisol and ascorbate levels Plasma cortisol (nM/l) Ascorbate (mmol/l) Malaria group (n=24) Non-infected controls (n=24) 1021.26±351.94* (range 304–1518) 19.52±5.77* 502.18±182.55* (range 93–799) 26.44±3.42* Data are means±SD. * Significantly different for malaria patients vs. controls. encountered in severe malaria.2,4,14 In the very limited number of comatose patients evaluated in the present study, mean plasma Phe level was as high as 242 mmol/l, a value four-fold the normal Phe concentration in plasma (Table 3). Plasma amino acid abnormalities characterize several health conditions including protein energy malnutrition (PEM),39,40 infections,7,28,41,42 severe trauma,43 and stress, as well as sepsis.44,45 In PEM, with the possible exceptions of His and Phe, whose plasma concentrations are marginally well maintained, all indispensable amino acids are reduced in concentration so that EAA/NEA ratio declines, but His/NEA ratio is slightly elevated.39,40,46 The activities of key Phe39,47 and His46,47 catabolic enzymes are reduced in PEM. In a study of stressed and/or septic patients, Vente and colleagues44 noted a 70% increase in plasma Phe over control level, with virtually all the other essential amino acids in plasma reduced by 10–30%, an observation prompting the suggestion that a correlation exists between plasma Phe levels and mortality during sepsis.44,45 There are also reports that in experimentally-induced sand-flyfever virus infection in healthy human adults, plasma amino acid levels compared with pre-inoculation control levels were Phe (+4%), Val (−33%), Thr (−26%), Leu (−33%), Ile (−31%), Tyr (−24%), Trp (−15%), Met (−16%) and His (−17%).42 In multiple-trauma patients compared with controls, plasma Phe is elevated (+33%) whilst its urinary excretion is increased by 13.3 times, mainly due to a faster clearance rate.48 What emerges from the numerous published studies on the alterations of plasma amino acid levels in infections, sepsis, and malnutrition is that: (i) not all individual essential amino acids change in exactly the same manner; (ii) the magnitude of the changes often correlates with the degree of the host’s febrile response; and (iii) the reported increases in plasma Phe in the various conditions do not approach the magnitude encountered in patients with severe malaria (Tables 1 and 3). It must also be emphasized that the critical factors underlying brain uptake of any individual amino acid under various conditions are not only the plasma level of the specific amino acid, but also the alterations in plasma concentrations of the amino acids that share the same transporter with the former at the BBB.18,26 The complex alterations in metabolism of individual amino acids in an infection are influenced by fever.7 The African child suffering from an acute episode of malaria may experience a resting energy expenditure increase of about 30%.3 The phenylalanine hydroxylating system complex consists of phenylalanine hydroxylase (PAH; EC 1.14.16.1), a regulatory cofactor tetrahydrobiopterin (THB), and dihydropteridine reductase (DHPR; EC 1.6.99.7) which keeps the cofactor in its active tetrahydro-form.49 DHPR deficiency and/or defective synthesis of THB, will elicit inadequate THB-dependent hydroxylase activities (Phe hydroxylase, Tyr hydroxylase, Trp hydroxylase), and consequently, impaired synthesis of dopamine, norepinephrine and serotonin, in addition to hyperphenylalaninaemia.49 In our study, patients pre-medicated with folic acid showed less prominent hyperphenylalaninaemia (Table 3), an observation suggestive of an increased dietary requirement for this vitamin in falciparum malaria and consistent with other reports of folate deficiency in severe malaria.50 Plasmodium falciparum possesses an endogenous folate synthesis Hyperphenylalaninaemia in malaria pathway, but also utilises exogenous folate.51 Studies of intraerythrocytic P. falciparum grown in continuous culture51 have shown that the parasite utilises pterin from exogenous folate degradation as a precursor for synthesis of 5-CH3-H4 Pte Glu5 (5-methyltetrahydrofolate), and that the extremely low rate of de novo synthesis from GTP or guanosine (30.7±9.2 pmol/0.1 ml packed cells/24 h) as compared with the rate of synthesis from exogenous folate, intact or degraded forms (1732± 207 pmol/0.1 ml packed cells/24 h) suggests a predominance of the latter pathway in the acquisition of folate cofactors for the parasites. We have no explanation for the observation that pre-treatment with folic acid reduced the changes in plasma phenylalanine and tyrosine levels in patients with malaria (Table 3). It is possible that severe malaria elicits deficient activity of DHPR through mechanisms that are still unclear. There are, however, suggestions that DHPR may be involved in other enzyme systems,52 and this enzyme may keep folate in the active, tetrahydro form.53 The latter role could explain the low serum folate levels observed in some PKU patients with DHPR deficiency,54 and the inclusion of tetrahydrofolate in the therapy for these patients.52,55 Phenylalanine is transported solely by the L-system,18,27 and its K at the BBB is 4- to 29-fold m lower than those for other large neutral amino acids which share the same transporter.27 As indicated in Table 2, malaria infection had no effect on the apparent K for Phe but elicited a significant increase m (+25%) in the apparent K for Trp, Tyr and His. m Consequently, the uptake of Phe into the brain was calculated to be double in malaria patients compared with the controls, while the uptake of Trp was significantly reduced (Table 2). Both tyrosine hydroxylase and tryptophane hydroxylase, ratelimiting enzymes in the syntheses of dopamine/ norepinephrine and serotonin, respectively, are competitively inhibited by increased phenylalanine.57 Loo58 has demonstrated serotonin deficiency in experimental hyperphenylalaninaemia. Similarly, in autopsied brains of PKU patients, Phe levels increase five-fold, Tyr and Trp levels are reduced, and brain contents of serotonin, dopamine and norepinephrine substantially reduced.59 Some workers17 have argued that the significantly reduced brain serotonin and norepinephrine levels in rodents infected with P. berghei may play a role in the occurrence of cerebral vasodilation in malaria. The occurrence of seizures in severe malaria2,4,5 may be related to decreased brain levels of serotonin and catecholamines (putative inhibitory neurotransmitters)60 resulting from hyperphenylalaninaemia-induced reduction in brain levels of tryptophan and tyrosine. In an animal model system of spontaneous seizures, brain levels 501 of the inhibitory monoamine neurotransmitters are significantly decreased.61 The markedly increased brain uptake of histidine in children with malaria (Table 2) would favour an elevated brain level of histamine.62 The K for m L-histidine carboxylase (EC 4.1.1.22) in the brain is much higher than the level that can be saturated by normal brain contents of free histidine.62 Thus, elevated brain levels of histidine would promote enhanced synthesis of histamine (imidazolethylamine).62,63 It is purely speculative at this stage whether or not the brain burden of histamine is increased in malaria, but this merits some careful studies, since elevated brain levels of this monoamine may promote increased cerebral capillary permeability, resulting in cerebral oedema and elevated intracranial pressure, among other effects.63 These are pathophysiological alterations associated with cerebral malaria.2,4 Nitric oxide (NO) is implicated in some aspects of the pathogenesis of severe malaria,64,65 and the significantly reduced plasma arginine observed in the malaria patients (Table 1) could be due to increased utilization of this amino acid by the nitric oxide synthase (NOS) pathway. Our studies also demonstrated a two-fold elevation in plasma level of free cortisol in the children with malaria compared with the non-infected group (Table 4), an observation consistent with reports by others10 and attributable to stimulation of the hypothalamus-pituitary-adrenal axis by pro-inflammatory cytokines.8–10 The increased circulating levels of glucocorticoids would play a role not only in mobilizing free amino acids from the periphery to the liver, but also in suppressing excessive/inappropriate cytokine production.7,9 The marked reduction of plasma ascorbate in malaria (Table 4) confirmed earlier reports by others,66 and could be due to reduced dietary intake, and enhanced utilization in cell mediated immunity as well as in free radical quenching. There are suggestions that there is a cerebral component in virtually all cases of falciparum malaria.14 Despite the very limited number of children with falciparum malaria examined in the present studies, the findings suggest an urgent need to evaluate some of the symptoms encountered in this disease within the context of major alterations in the metabolism of monoamines in the brain. It is perhaps relevant that the consumer-initiated complaints associated with excessive intake of aspartame (L-aspartylL-phenylalanine methyl ester)-containing food products include mood changes, insomnia, seizures, nausea, diarrhoea, abdominal pain, and irregular menses.67 Some of these are features of severe malaria.1,2,4,5 Unlike blood levels of aspartic acid, blood concentrations of phenylalanine rise markedly after ingestion of aspartame, and the rise is linearly related to the dose of aspartame.68 The absence of 502 C.O. Enwonwu et al. any substantial increase in plasma aspartic acid level precludes this amino acid from participating in the observed changes.60 17. Acknowledgements 18. This study was supported in part by the Nestle Foundation, Lausanne, Switzerland. The excellent administrative assistance of Ms. Judy Pennington is also acknowledged. 19. 20. References 1. Greenwood B, Marsh K, Snow R. Why do some African children develop severe malaria. Parasitol Today 1991; 7:277–81. 2. Molyneux ME, Taylor TE, Wirima JJ, Bogstein A. Clinical features and prognostic indicators in paediatric cerebral malaria: a study of 131 comatose Malawian children. Q J Med 1989; 71:441–59. 3. Stettler N, Schutz Y, Whitehead R, Jequier E. Effect of malaria and fever on energy metabolism in Gambian children. Ped Res 1992; 31:102–6. 4. Crawley J, Smith S, Kirkham F, Muthini P, Waruiru C, Marsh K. Seizures and status epilepticus in childhood cerebral malaria. Q J Med 1996; 89:591–7. 5. Walker O, Salako LA, Sowunmi A, Thomas JO, Sodeinde O, Bondi FS. Prognostic risk factors and post-mortem findings in cerebral malaria in children. Trans Roy Soc Trop Med Hyg 1992; 86:491–3. 6. Solomons NW, Keusch GT. Nutritional implications of parasitic infections. Nutr Rev 1981; 39:149–61. 7. Beisel WR. Infection-induced malnutrition: from cholera to cytokines. Am J Clin Nutr 1995; 62:813–19. 8. Baptista JL, Vanham G, Wery M, Marck EV. Cytokine levels during mild and cerebral falciparum malaria in children living in a mesoendemic area. Trop Med Int Hlth 1997; 2:673–9. 9. Rook GAW, Hernandez-Pando R, Lightman SL. Hormones, peripherally activated prohormones, and regulation of the Th1/Th2 balance. Immunol Today 1994; 15:301–3. 10. Dekker E, Romijn JA, Moeniralam HS, Waruiru C, Ackermans MT, Timmer JG, Endert E, Peshu N, Marsh K, Sauerwein HP. The influence of alanine infusion on glucose production in ‘malnourished’ African children with falciparum malaria. Q J Med 1997; 90:455–60. 11. Meier CA. Mechanisms of immunosuppression by glucocorticoids. Eur J Endocrinol 1996; 134:50. 12. Sowunmi A. Hepatomegaly in acute falciparum malaria in children. Trans Roy Soc Trop Med Hyg 1996; 90:540–2. 13. Anstey NM, Granger DL, Weinberg JB. Nitrate levels in malaria. Trans Roy Soc Trop Med Hyg 1997; 91:238. 14. Desowitz RS. The pathophysiology of malaria after Maegraith. Ann Trop Med Parasitol 1987; 81:599–606. 15. Rossi-Fanelli F, Freund H, Krause R, Smith AR, Howard James J, Castorina-Ziparo S, Fischer JE. Induction of coma in normal dogs by the infusion of aromatic amino acids and its prevention by the addition of branched-chain amino acids. Gastroenterol 1982; 83:664–71. 16. Abumrad NN, Miller B. The physiology and nutritional 21. 22. 23. 24. 25. 26. 27. 28. 29. 30. 31. 32. 33. 34. 35. significance of plasma free amino acid levels. J Parent Enteral Nutr 1983; 7:163–70. Roy S, Chattopadhyay RN, Maitra SK. Changes in brain neurotransmitters in rodent malaria. Indian J Malariol 1993; 30:183–5. Pardridge WM. Brain metabolism: A perspective from the blood-brain barrier. Physiol Rev 1983; 63:1481–535. Michalak A, Butterworth RF. Selective increases of extracellular brain concentrations of aromatic and branched-chain amino acids in relation to deterioration of neurological status in acute (ischemic) liver failure. Metabol Br Dis 1997; 12:259–69. Siddiqui WA, Trager W. Free amino acids of blood plasma and erythrocytes of normal ducks and ducks infected with malarial parasite, Plasmodium lophurae. Nature 1967; 214:1046–7. Sherman IW. Transport of amino acids and nucleic acid precursors in malarial parasites. Bull WHO 1977; 55:211–25. Warrell DA, Molyneux ME, Beales PF. Severe and Complicated Malaria. Trans Roy Soc Trop Med Hyg 1990; 84 (Supplement 2):1–65. World Health Organization. Advances in Malaria Chemotherapy, Technical Report Series 711, 1984: 2–30. NCHS. Growth Curves for Children from Birth to 18 years. United States Department of Health, Education and Welfare. DHEW Publication PHS 78–1650: 1977. Heinrikson R, Meredith SA. Amino acid analysis by reversephase HPLC: precolumn derivatization with phenylisothiocyanate. Anal Biochem 1984; 136:65–74. Pardridge WM. Blood-brain barrier carrier-mediated transport and brain metabolism of amino acids. Neurochem Res 1998; 23:635–44. Hargreaves KM, Pardridge WM. Neutral amino acid transport at the human blood-brain barrier. J Biol Chem 1988; 263:19392–7. Enwonwu CO, Falkler WA, Idigbe EO, Afolabi BM, Ibrahim M, Onwujekwe D, Savage KO, Meeks V. Pathogenesis of cancrum oris (noma): confounding interactions of malnutrition with infection. Am J Trop Med Hyg 1999; 60:223–32. Vanderjagt DJ, Garry PJ, Bhagavan HN. Ascorbic acid intake and plasma levels in healthy elderly people. Am J Clin Nutr 1987; 46:290–4. Jacob RA. Assessment of human vitamin C status. J Nutr 1990; 120:1480–5. DeOnis M, Monteiro C, Akre J, Clugston G. The worldwide magnitude of protein-energy malnutrition: an overview from the WHO global database on child growth. Bull WHO 1993; 71:703–12. Fernstrom JD, Wurtman RJ. Brain serotonin content: physiological regulation by plasma neutral amino acids. Science 1972; 178:414–16. Enwonwu CO. Amino acid availability and control of histaminergic systems in the brain, In: Huether G. ed. Amino Acid Availability and Brain Function in Health and Disease, NATO ASI Series, Vol H20, 1988:167–73. Knox WE. Phenylketonuria. In: Stanbury JB, Wyngaarden JB, Fredrickson DS. eds. The Metabolic Basis of Inherited Disease. New York, McGraw-Hill, 1972:266–95. Jeevanandam M. Trauma and sepsis. In: Cynober LA, ed. Amino Acid Metabolism and Therapy in Health and Hyperphenylalaninaemia in malaria 36. 37. 38. 39. 40. 41. 42. 43. 44. 45. 46. 47. 48. 49. 50. 51. 52. Nutritional Disease. Boca Raton FL, CRC Press, 1995:245–55. White NJ, Ho M. The pathophysiology of malaria. Adv Parasitiol 1992; 31:83–173. Scriver CR, Clow CL. Phenylketonuria: epitome of human biochemical genetics. N Engl J Med 1980; 303:1336–42. Kaufman S. Regulation of the activity of hepatic phenylalanine hydroxylase. In: Weber G, ed. Advances in Enzyme Regulation, Vol. 25. Oxford, Pergamon Press, 1986:37–64. Jackson AA, Grimble RF. Malnutrition and amino acid metabolism. In: Suskind RM, Lewinter-Suskind, eds. The Malnourished Child. Nestle Nutrition Workshop Series, Vol. 19. New York, Vevey/Raven Press, 1990:73–94. Alleyne GAO, Hay RW, Picou DI, Stanfield JP, Whitehead RG. Protein-Energy Malnutrition. London, Edward Arnold, 1977:54–62. Wannemacher, Jr. RW, Pekarek RS, Bartellon PJ, Vollmer RT, Beisel WR. Changes in individual plasma amino acids following experimentally induced sand fly fever virus infection. Metabolism 1972; 21:67–76. Wannemacher Jr RW. Key role of various individual amino acids in host response to infection. Am J Clin Nutr 1977; 30:1269–80. Jeevanandam M. Trauma and sepsis. In: Cynober LA, ed. Amino Acid Metabolism and Therapy in Health and Nutritional Disease. Boca Raton, CRC Press, 1995:245–55. Vente JP, Von Meyenfeldt MF, Van Eijk HMH, Van Berlo CLH, Gouma DJ, Van Der Linden CJ, Soeters PB. Plasma amino acid profiles in sepsis and stress. Ann Surg 1989; 209:57–62. Freund H, Atamian S, Holroyde J, Fischer J. Plasma amino acids as predictors of the severity and outcome of sepsis. Ann Surg 1979; 190:571–6. Antener I, Verwilghen AM, Van Geert C, Mauron J. Biochemical study of malnutrition. VI: Histidine and its metabolites. Internat J Vit Nutr Res 1982; 53:199–209. Edozien JC, Obasi ME. Protein and amino acid metabolism in kwashiorkon. Clin Sci 1965; 29:1–24. Jeevanandam M, Young DH, Ramias L, Schiller WR. Aminoaciduria of severe trauma. Am J Clin Nutr 1989; 49:814–22. Dhondt JL, Farriaux JP. Atypical cases of phenylketonuria. Eur J Pediatr 1987; 146:A38–43. Migasena P, Areekul S. Capillary permeability function in malaria. Ann Trop Med Parasitol 1987; 81:549–60. Krungkrai J, Webster HK, Yuthavong Y. De novo and salvage biosynthesis of pteroylpetaglutamates in the human malaria parasite, Plasmodium falciparum. Mol Biochem Parasitol 1989; 32:25–38. Kaufman S. Tetrahydrobiopterin and hydroxylation systems 53. 54. 55. 56. 57. 58. 59. 60. 61. 62. 63. 64. 65. 66. 67. 68. 503 in health and disease. In: Lovenberg W, Levine RA, eds. Unconjugated Pterins in Neurobiology: Basic and Clinical Aspects. London, Taylor and Francis, 1987:1–28. Pollock RJ, Kaufman S. Dihydrofolate reductase is present in brain. J Neurochem 1978; 30:253–6. Kaufman S, Holtzman N, Milstein S, Butler IJ, Krumholz A. Phenylketonuria due to a deficiency of dihydropteridine reductase. N Engl J Med 1975; 293:785–90. Kaufman S. Phenylketonuria and its variants. In: Harris H, Hirschhorn K, eds. Advances in Human Genetics, Vol 13. New York, Plenum Press, 1983:217–97. Choi TB, Pardridge WM. Phenylalanine transport at the human blood-brain barrier. Studies with isolated human brain capillaries. J Biol Chem 1986; 261:6536–41. Maher TJ. Modification of synthesis, release, and function of catecholaminergic systems by phenylalanine. In: Huether G, ed. Amino Acid Availability and Brain Function in Health and Disease. NATO ASI Series, Vol. H20, 1988:201–6. Loo YH. Serotonin deficiency in experimental hyperphenylalaninemia. J Neurochem 1974; 23:139–47. McKean CM. The effects of high phenylalanine concentrations on serotonin and catecholamine metabolism in the human brain. Brain Res 1972; 47:469–76. Pardridge WM. Potential effects of the dipeptide sweetener aspartame on the brain. In: Wurtman RJ, Wurtman JJ, eds. Nutrition and the Brain, Vol. 7. New York, Raven Press, 1986:199–224. Jobe PC, Ko KH, Dailey JW. Abnormalities in norepinephrine turnover rate in the central nervous system of the genetically epilepsy-prone rat. Brain Res 1984; 290:357–60. Enwonwu CO, Okolie EE. Differential effects of protein malnutrition and ascorbic acid deficiency on histidine metabolism in the brain of infant nonhuman primates. J Neurochem 1983; 41:230–8. Schwartz JC, Arrang JM, Garbarg M, Pollard H, Ruat M. Histaminergic transmission in the mammalian brain. Physiol Rev 1991; 71:1–51. Grau GE, de Kossodo S. Cerebral malaria: mediators, mechanical obstruction or more? Parasitol Today 1994; 10:408–9. Clark IA, Rockett KA. The cytokine theory of human cerebral malaria. Parasitol Today 1994; 10:410–12. Thurnham DI, Singkamani R, Kaewichit R, Wongworapat K. Influence of malaria infection on peroxyl-radical trapping capacity in plasma from rural and urban Thai adults. Br J Nutr 1991; 64:257–71. Centers for Diseases Control. Evaluation of Consumer Complaints Related to Aspartame Use. CDC, 1984. Stegink LD. Aspartame metabolism in humans: acute dosing studies. In: Stegink LD, Filer LJ, eds. Aspartame Physiology and Biochemistry. New York, Marcel Dekker, 1984:509–53.