* Your assessment is very important for improving the workof artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download CP11/31 - Mortgage Market Review - updated 1/2/12

Securitization wikipedia , lookup

Syndicated loan wikipedia , lookup

Household debt wikipedia , lookup

Federal takeover of Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac wikipedia , lookup

Interbank lending market wikipedia , lookup

Public finance wikipedia , lookup

Security interest wikipedia , lookup

Credit rationing wikipedia , lookup

Financialization wikipedia , lookup

Peer-to-peer lending wikipedia , lookup

Moral hazard wikipedia , lookup

Interest rate ceiling wikipedia , lookup

Continuous-repayment mortgage wikipedia , lookup

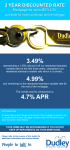

Adjustable-rate mortgage wikipedia , lookup

United States housing bubble wikipedia , lookup

Yield spread premium wikipedia , lookup

Mortgage broker wikipedia , lookup