* Your assessment is very important for improving the workof artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download About Medieval Europe - Core Knowledge Foundation

Holy Roman Empire wikipedia , lookup

Role of Christianity in civilization wikipedia , lookup

Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse wikipedia , lookup

History of Christianity wikipedia , lookup

Christian culture wikipedia , lookup

History of Christian thought on persecution and tolerance wikipedia , lookup

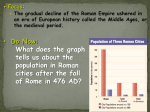

Christendom wikipedia , lookup

CK_4_TH_HG_P087_242.QXD 10/6/05 9:02 AM Page 111 Representative Peoples in the Roman Empire Among the peoples who settled in what had been the Roman Empire were the Vandals in Gaul and Spain, the Franks in Gaul, and the Angles and Saxons in England. The English words vandal and vandalism are derived from the Vandals, a Germanic group that invaded western Europe in the 400s CE. They had originated in the area south of the Baltic Sea and moved west beginning in the 300s gated by William the Conquer The Middle Ages The term Middle Ages refers to European culture and was coined to denote the time between the end of the Roman Empire and the beginning of the Renaissance. While other cultures may have had their own middle ages, they do not coincide with this era in European history. The term Middle Ages itself is a historical term and a result of some prejudice by Renaissance and later historians, who also called the period the Dark Ages. The early Middle Ages, roughly from the fall of Rome to around 1100 CE, were grim times for most of Europe; lawlessness was common and invasion was a recurrent event. The one exception was the period around the reign of Charlemagne (774–814 CE). Beginning around 1050 CE, however, a civilization took form that saw such achievements as the beginnings of the growth of trade and towns, the rule of law, the Crusades, the flourishing of courtly love, chivalry, Gothic cathedrals, and more. The official end of the Roman Empire in the West is considered to have come in 476 CE, when Odoacer, a German war leader, deposed the last Roman emperor. But the changes in the West had begun long before. The authority of Rome and Roman law had gradually been eroded along the frontier. What was left of the government structure of the Roman Empire in the provinces soon disintegrated. The Germanic groups who had moved into the empire had neither codified legal History and Geography: World 111 CK_4_TH_HG_P087_242.QXD 10/6/05 9:02 AM Page 112 II. Europe in the Middle Ages systems nor organized government on a large scale. They did not live in cities and did not participate in complex trading networks. They were nomadic herders and farmers who lived in small communities and were governed by local chiefs or kings who based their rule on custom and tradition. None of the nomadic peoples had written languages. In the years after the end of the Roman Empire and the ascendancy of the Germanic peoples, the trading networks of the old empire broke down. Education and the arts suffered from lack of interest. People retreated to their landholdings and looked to local warlords to secure law and order. In this absence of governmental organization, two institutions emerged as central to the establishment of order—the Church and feudalism. C. Developments in the History of the Christian Church Teaching Idea Before discussing the spread of Christianity in the medieval period, you may wish to review with students the early history of the religion and its spectacular growth during the time of the Roman Empire. Christianity grew out of Judaism. At the time of the death of Jesus, there were only a handful of Christians. The apostles, especially St. Paul, helped spread the religion throughout the Mediterranean. Christianity continued to grow steadily, despite occasional persecution. However, it remained a minority religion (most Romans were polytheists who worshipped many gods) until the conversion of the emperor Constantine in 312. After the emperor converted, Christianity rapidly became the dominant religion of the Roman Empire. Growing Power of the Pope During the early Middle Ages, the church that later became known as the Roman Catholic Church was the single largest and most important organization in western Europe. The Church provided stability in the face of political upheavals and economic hardships. This stability was evident both in its organization and in its message: life on Earth might be brutally hard, but it was the means to a joyful life in heaven. Christians during the early Middle Ages looked at life on Earth as a time of testing and preparation for life after death. In general, although not everyone in the early Middle Ages was religious, many people were. And even those who were not especially religious in their personal beliefs may have appreciated the order and structure that Christianity brought to everyday life. Because of the central position of the Church in the West, the pope, the head of the Church in the West, grew from a local Roman authority to become a powerful secular as well as religious figure by the end of the 11th century. As the Christian church grew during the time of the Roman Empire, it developed a structure and a hierarchy. At the local level was the parish, a congregation of worshippers in a local community who were looked after by a priest. Many parishes made up a diocese overseen by a bishop. Several dioceses were then combined into a province overseen by an archbishop. At the top of the Church was the pope, also known as the Bishop of Rome. Over the years, power slowly transferred from bishops as a group to the pope as an individual. By the 11th century, in part through the doctrine of Petrine supremacy (St. Peter is considered the first pope), popes claimed the authority of God on Earth; that is, what they said and did reflected God’s will. Based on this concept, popes sometimes extended their authority to claim papal supremacy over secular rulers. Wielding political influence and the threat of excommunication—withholding the sacraments from an individual—various popes enforced and enlarged the power of the Church. A new level of papal power was achieved during the reign of Pope Innocent III from 1198 to 1216 CE. Innocent III set standards for regular worship among lay Christians; he approved new religious orders; and he built up the role of the papacy as the main forum for diplomacy among European political leaders, such that leaders often felt compelled to follow his decisions. 112 Grade 4 Handbook