* Your assessment is very important for improving the work of artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download Chapter 1: Mendel`s breakthrough: patterns, particles and principles

Survey

Document related concepts

Transcript

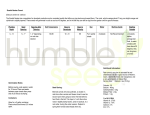

Chapter 1: Mendel’s breakthrough: patterns, particles and principles of heredity please read pages 10 through 13 R. Ward: Spring 2001 Slide 1 of Chapter 1 •One of Mendel’s express aims was to understand how first generation traits (parents) would disappear in the second generation (F1 or hybrid) and reappear in the third generation (F2) •Gregor Mendel conducted experiments with peas between 1857 and 1863 lPresented results in 1865 lPoorly received/understood: Karl Wilhelm von Nageli, a noted Swiss botanist. Nageli, whose thinking sometimes veered from science to mysticism, dismissed Mendel's work Note: Correns, one of three re-discoverers in 1900, was a nephew of Nageli! 1 Plant life cycles Endosperm is 3N 2 copies of egg chromosomes, 1 of sperm Maternal tissue: seed coat=ovule wall Pod/fruit wall= ovary wall From: Plant Life Cycles and Angiosperm Development: Susan R. Singer from Embryology: Constructing the Organism (S.F. Gilbert and A. M. Raunio, eds.) 1997. Sinauer Associates, Sunderland, MA. Seed First 2N cell=zygote Sperm and eggs= gametes (N) Slide 2 of Chapter 1 R. Ward: Spring 2001 •Review the life cycles of plants and be familiar with these terms: lSporophytic lGametes or maternal tissue (sperm and eggs) lpollination and Fertilization lZygote 2 Mendel’s Experimental Organism R. Ward: Spring 2001 Slide 3 of Chapter 1 •experimental organism was the garden pea: advantagesØnaturally self pollinated which generates “true breeding” plants (later we’ll call these homozygous plants) Øeasily cross fertilized or cross-pollinated Øreadily available clear-cut alternative forms of traits Øseed traits (color, shape) allowed for easy generation of large data sets 3 Mendel’s traits Slide 4 of Chapter 1 R. Ward: Spring 2001 ltwo of Mendel’s traits exhibited Xenia •XENIA: genetic differences among pollen grains can manifest as phenotypic differences in seed set on female parent in P generation. lXenia genes expressed in embryo (including cotyledons) or endosperm. But not seed coat or pod attributes lgenotypes of both egg and pollen determine phenotype lphenotype of F1 generation manifest in F1 seeds produced on true breeding female parent. •Phenotype could vary within a pod •seed shape: round vs wrinkled – embryo/cotyledon trait •seed color: yellow vs green lMendel referred to this as “albumen” color lactually is color of cotyledon, which is embyronic tissue lfive of Mendel’s traits manifest in flowers, pods or stem morphology •phenotype of F1 generation manifest in plants grown from seeds produced by cross pollination •pod shape: inflated vs constricted lNote: P generation pods contain F1 seed, and F1 pods contain F2 seeds, etc.! lTherefore, parental generation pods have same genotype and phenotype irrespective of pollen genotype •pod color: green vs yellow •flower/pod position: axillary vs terminal •stem length: standard vs dwarf 4 Fn seed vs. Fn plants pollen P plant P plant Male (pollen source) Female (emasculated) F1 F2 plants F1 seed P seed R. Ward: Spring 2001 P seed F2 seed Slide 5 of Chapter 1 •P generation fruit tissue (ovary walls=pericarp, ovule walls=seed coat) is derived from cells that are direct descendents of the parental mitotic divisions of the zygote/embryo in the seed from which the P generation plant arose. All such tissue is therefore genetically identical on a single plant, even if the P generation plant was pollinated/fertilized by a genetically different plant. •Seeds on P generation plants used as females in a cross-fertilization carry F1 generation embryos. •Seeds can have three distinct tissuesØembryo, including cotyledons (can be different from mother plant) Øseed coat (derived from maternal tissue just like the fruit wall or pericarp is) Øendosperm- derived from union of two clones of the egg and one clone of the sperm •The embryo represents the progeny, so fruits and seeds are bi-generational. •This is important when considering mendel’s experiments since some traits are expressed in embryonic tissue which is enclosed within ovule walls (seed coats) and ovary walls (pericarp) 5 Xenia in Pea P1 male •purple flower •yellow seeds •yellow pod P1 female •white flower •green seeds •green pod true breeding (all progeny from self pollination identical to mother plant) R. Ward: Spring 2001 F1 seed •all seed on female in the cross will have yellow seed (since seed color is an embryonic trait, and yellow is dominant to green) •but pods are maternal tissue and not affected by the pollen genotype F1 plant •purple flower only •Seeds: ¼ green, ¾ yellow •green pod only Slide 6 of Chapter 1 •segregation for xenia traits can be viewed among seeds within pods of F1 plants. •segregation for non-xenia traits only manifest on plants derived from the seed on the F1 plants (i.e., F2 seed). 6 Gregor Mendel: context and tools • Background: the historical puzzle of inheritance Fig. 1.6 from Hartwell et al •Genetics involves: Øcareful observation of populations over generations R. Ward: Spring 2001 Slide 7 of Chapter 1 Øanalysis of carefully acquired data on individuals Ødevelopment and testing of theoretical frameworks •Mendel was the first person to put these three elements together to form a theory of inheritance Øa great deal of observation took place in the time before Mendel -huge efforts at cataloging species was conducted (Linnaeus, Darwin) -cross fertilization within and among species was induced and observed •Artificial selection was the first applied genetic practice Øplants and animals were domesticated through selection of individuals that exhibited favorable traits (e.g., nonaggressiveness in the progenitors of domesticated dogs, horses, cattle etc.; longer seed retention in cereals, etc.) •The puzzle of passing on desirable traits Øby Mendel’s birth (1822), plant and animal breeders were able to generate individuals with new and valued combinations of traits by controlled matings Øbut the value of these progeny as parents was unpredictable (i.e., the value of an individuals own progeny was unpredictable) •Sheep breeding was a particularly important activity in Moravia, and at a 1837 conference of the Moravian Sheep Breeders Society, the Abbott Cyril Napp proposed that breeders needed to discover three things: Øwhat is inherited Øhow is it inherited, and Øwhat is the role of chance in inheritance? •before Mendel, blending, preformation (e.g., the idea of a homunculus) and other erroneous theories were proposed to explain the contradiction between 1) the obvious reality that members of a species had progeny who were of the same species; and 2) the equally obvious reality that variation of individual phenotype (appearance) exists within and among families •Mendel’s work laid the foundation for our current view of heredity •Key features of his approach include: Øfocus on a single species, the naturally self-pollinated but easily cross-pollinated annual pea (Pisum sativum) Øfocus on traits that had distinct, mutually exclusive (“antagoni -furthermore- Mendel worked with only two forms of each of the seven traits he studied Øselection and propagation of “pure-breeding lines” which upon self-pollination produce progeny that are collectively identical in form to their parents and to each other. Pure-breeding lines in a self-pollinated crop can be maintained in a pure state throughout multiple generations simply by isolating their progeny from other lines. Øcareful control of matings between plants of different pure-lines, with attention to which parent was used as the female. Øgeneration of large datasets consisting of observations on individual progeny plants -note that the word ‘plant’ here is inclusive of the embryo within a seed. Øcomparison of such results with predictions based on hypothetical models 7 Creating a monohybrid P1 male •yellow seeds P1 female •green seeds F1 seed •all seed on female in the cross will have yellow seed (since seed color is an embryonic trait, and yellow is dominant to green) true breeding (all progeny from self pollination identical to mother plant) R. Ward: Spring 2001 Slide 8 of Chapter 1 •Genetic Analysis According to Mendel •The embryos (i.e., progeny plants) that develop within the seeds of a plant used as a female in a cross (or hybridization) are deemed an “F1” generation if the parents differed in at least one trait. •analyses of the progeny of plants grown from the F1 seed was the basis of Mendel’s work •Mendel began his work by focusing on one trait at a time Øanalysis of the frequencies of alternate forms of a single trait in the P, F1, subsequent generations of one cross is called “Monohybrid analyses” Øin reality, the parents used in Mendel’s monohybrid crosses must have differed for other traits. Øthe key is that Mendel ignored the other traits and focused on only one at a time (at first) 8 P, F1, and F2 generations R. Ward: Spring 2001 Slide 9 of Chapter 1 •Figure 1.9: Monohybrid analysis of seed color in pea (an embryonic trait) •Mendel took pollen from a yellow seeded pure breeding line and placed it on stigmas of emasculated flowers of plants from a green seeded pure breeding line •The F1 seeds (which matured in the pods on the female parent), were all yellow Øthe reciprocal cross was also made (using the yellow seeded pure breeding line as the male parent) Øagain, all of the F1 seeds were yellow •Mendel planted the F1 seeds and allowed them to self pollinate and develop mature seed. •The F2 seeds (which matured on the F1 plants) included both yellow and green forms of the seed color trait, in a ratio of approximately 3 yellow for every 1 green seed. •These results refuted the concept of blending, since the green form of the trait in the P generation reappeared in the F2 generation after disappearing in the F1 generation. •Mendel observed that there are two kinds of behavior of yellow pea derived plants: Øsome breed true (have only yellow seed progeny upon self pollination) Øsome generate both yellow and green seed upon self pollination •Mendel hypothesized that Ø1) for each trait, each plant carries two discrete copies of a unit of inheritance (which we now call genes) Ø2) these genes come in two forms, which we now call “alleles” Ø3) one allele is dominant and the other is recessive -the yellow allele of the seed color gene in pea is dominant to the green allele of the same gene. •The P generation plants in Fig. 1.9 either carry two dominant alleles (the yellow parent), or two recessive alleles (the green parent) •F1 generation seeds in Figure 1.9 carry one yellow and one green allele. •end •end 9 The Law of Segregation R. Ward: Spring 2001 Slide 10 of Chapter 1 •Figure 1.10: The law of segregation is two part Ø1) gametes (sperm and eggs) contain only one allele of a given gene; -pure breeding yellow peas form gametes that all have the yellow allele, and -pure breeding green peas form gametes that all have the green allele -F1 generation plants form both kinds of gametes in equal quantities ( ½ with the yellow allele, and ½ with the green allele). -in other words, both alleles can reside in and pass through an F1 generation without any change in their fundamental behavior -so alleles are SEGREGATED from each other in gamete formation Ø2) Individual progeny are created from the random union of one male gamete and one female gamete. 10 Self pollination of the F1 Generation R. Ward: Spring 2001 Slide 11 of Chapter 1 •gametes have only one allele (Y or y) •the two alleles of an F1 appear in equal frequencies in that F1’s gametes •since the frequency of ‘Y’ equals the frequency of ‘y’ in both eggs and pollen of an F1, •the probability of a random male gamete carrying ‘Y’ = 0.5, which equals the probability of it carrying the ‘y’ allele •gametic union in self fertilization is random, leading to four possible ways to form a zygote: Ø (egg-derived written first): Yy, YY, yY, and yy •each of those outcomes has a probability of ¼, by two lines of reasoning: Ønone of the four is more likely than the other, so they are equally probable Øthe “Law of the Product” states that the probability of two (or more) independent events occurring simultaneously ( or sequentially) equals the product of the probabilities of the individual events. 11 The outcomes of two “events” are independent if they satisfy two constraints: v1) the outcome of one event doesn’t influence the outcome of the other event; and v2) they can occur together (i.e., they are not mutually exclusive) vexamples: Ø two consecutive coin tosses- one coin doesn’t influence the other; and it’s possible to do Ø a ‘Y’ egg combining with a ‘y’ sperm- the probability of the egg being ‘Y’ is not affected by the identity of the sperm; and zygotes always derive from one sperm and one egg R. Ward: Spring 2001 Slide 12 of Chapter 1 12 Law of the Sum v if an event can be achieved by two or more mutually exclusive routes, the probability of the event equals the sum of all possible routes. v the Yy genotype in the F2 generation depicted in both Figures 1.9 and 1.11 can occur in one of two mutually exclusive routes: Ø Ø v Since the probability of both routes equals 0.5, and they are mutually exclusive, we add the probabilities to determine the probability of a heterozygous F2 plant. R. Ward: Spring 2001 Slide 13 of Chapter 1 •“events” are in the eye of the beholder •possible events in the context of genetics: Øthe genotype of a gamete randomly selected from one plant Øthe phenotype of a plant randomly selected from a population of plants Øa zygote is formed by union of an egg carrying ‘Y’ and a sperm c Øa zygote is formed by union of an egg carrying ‘Y’ and a sperm c 13 Laws of probability in Action just one way to form YY or yy two mutually exclusive ways to achieve Yy R. Ward: Spring 2001 Slide 14 of Chapter 1 14 Frequencies and ratios vFrequencies are used in genetics to represent the proportion that one class of individuals represents of a whole population. vA list of the frequencies of all classes is a “frequency distribution”. A complete frequency distribution must sum to 1.0 . vWe often speak of “ratios” in genetics. Frequency distributions are converted to ratios by using the numerator of the fractional frequencies after application of a common denominator. R. Ward: Spring 2001 Slide 15 of Chapter 1 15 Frequencies and corresponding ratios: examples vBelow are examples of frequency distributions and their corresponding ratios Frequency distribution Ratio 0.75 yellow, 0.25 green 3 yellow : 1 green 0.25 YY, 0.5Yy, 0.25 yy 1 YY : 2 Yy : 1 yy 0.8 tall, 0.2 short 4 tall : 1 short R. Ward: Spring 2001 Slide 16 of Chapter 1 16 Inter-converting frequencies and ratios v Assume you have 25 blue, 50 green, and 25 black marbles for a total of 100 marbles. v The Frequency distribution of marble colors is 1/4 blue : 1/2 green : 1/4 black . v The ratio of marble colors is 1 : 2 : 1 (blue/green/black) v To convert from fractional frequencies to ratios, Ø apply a common denominator to each frequency, (in this case the common denominator is 4, so the freq. dist. becomes 1/4 blue : 2/4 green : 1/4 black). Ø Then use the numerators to represent the ratios: 1 blue : 2 green : 1 black. v To convert a ratio to frequencies, Ø sum each of the values in the ratio expression (in this case 1, 2 and 1, which sums to 4) ; Ø and use that as the denominator under each of the ratio values. So a ratio of 1 : 2 :1 translates into a frequency distribution of 1/4 : 2/4 : 1/4. R. Ward: Spring 2001 Slide 17 of Chapter 1 17 Ratios and Frequencies of a subset of classes v Ratios among classes remain constant even if one or more classes is discarded v If we discard all of the black marbles from the slide above, the ratio of blue to green marbles is unchanged and remains: Ø 1 blue : 2 green v But the frequencies in an original population do not equate with the correct frequencies in a subset of classes. We had 1/4 blue and 1/2 green when we had the black marbles included, but that cannot be a complete frequency distribution since it does not sum to 1.0 . v To derive the correct frequencies of a subset of classes, first write down the ratios (1 : 2), and then convert that to a frequency distribution. The sum of ratio values is 1+2=3, so using 3 as the denominator, the ratio of 1 : 2 converts to a frequency distribution of 1/3 and 2/3. R. Ward: Spring 2001 Slide 18 of Chapter 1 18 Frequencies and Ratios: an application (1 of 2) ¼ ¼ 1/4 YY ¼ ¼ 1/4 yy 2/4 Yy •Ratio of homozygous to heterozygous Yellow F2 Progeny: 1 YY : 2 Yy; •Which is equivalent to a frequency distribution of 1/3 YY and 2/3 Yy R. Ward: Spring 2001 Slide 19 of Chapter 1 From fig. 1.12, Hartwell •When we look only at the yellow progeny we are •If you know the ratio of the occurrences of two events (for instance 1 YY for every 2 Yy), you can convert the ratio into frequency distribution (frequency of each type of event- 1/4, 1/2, etc.) by summing the values in the ratio ( in this case 2+1) and using that sum as a denominator for each events ratio value. 19 Frequencies and Ratios: an application (2 of 2) Yellow F2’s YY Yy 1/3 YY 2/3 Yy Self pollination F3 1/3 * [1/1 YY] =4/12 YY 2/3 * [1/4 YY 2/4 Yy 1/4 yy] = 2/12 YY 4/12 Yy 2/12 yy Ratio 6(=4+2) YY : 4 Yy :2 yy Yellow F3’s Ratio 6 YY : 4 Yy Frequencies 6/10 YY, 4/10 Yy; or 3/5 YY, 2/5 Yy R. Ward: Spring 2001 Slide 20 of Chapter 1 •Why multiply the frequencies of genotypes derived from Yy by 2/3? •Because two independent events are required for a given genotype to occur in the progeny of a Yy F2 plant. Øfirst, the F2 had to be Yy. That probability is 2/3 Øsecond, the probability of, say, YY is 1/4 in the progeny of a Yy F2 •Since these two events are independent, we multiply the two probabilities: 2/3 * 1/4 = 2/12 20 Some Definitions R. Ward: Spring 2001 Slide 21 of Chapter 1 •Phenotype- appearance •Genotype- Alleles present in cells of a plant for one or more genes •Homozygous- both alleles of a gene are identical •Heterozygous- the two alleles are different 21 Further proof of the law of segregation and Ratios: Progeny testing of F2 seed ¼ 1/4 YY ¼ ¼ ¼ 1/4 yy 2/4 Yy •Ratio of homozygous to heterozygous Yellow F2 Progeny: 1 YY : 2 Yy; •Which is equivalent to a frequency distribution of 1/3 YY and 2/3 Yy R. Ward: Spring 2001 Slide 22 of Chapter 1 From fig. 1.12, Hartwell •As shown earlier, self-pollination of an F1 plant generates F2 seed that has a segregation ratio of 3:1 yellow to green seeds 22 Mendels experiments 1 of 2 pure-breeding (plant, grow, collect pollen) P plant x pure-breeding (plant, grow, grow, emasculate) Harvest ->F2 seed: 3:1 ratio of yellow to green seeds (in pods of F1 plants) 1/3 Y breed true 2/3 Y segregate F2 plants P plant F1 plant(s) F2 plant F2 plants Harvest-> F1 seed:all yellow (in pods of female plant) Slide 23 of Chapter 1 R. Ward: Spring 2001 all green F3 (pure breeding) •Mendel’s Monohybrid experiment with seed color (an embryo trait) •F2 segregated in a 3:1 ratio of yellow to green (F2 seed is in F1 plant pods) •Progeny tests of F2 seed were conducted Øgrow F2 plants from F2 seed Øharvest F3 seed from each plant separately, categorize F2 plants as having progeny that are: -all green (pure breeding green- yy homozygotes) -all yellow (pure breeding yellow- YY homozygotes) - 3:1 yellow to green segregation- Yy heterozygotes ØResults showed : •that all green F2 seeds produced plants that on self pollination had only green seeds. •1/3 of yellow F2 seeds produced plants that on self pollination had only yellow seeds, and •2/3 of yellow F2 seeds produced plants that on self pollination had yellow and green seeds in a 3:1 ratio •Mendel also conducted test crosses of F2 plants yellow F2 seeds Øcross yellow F2 plants with pure breeding green parent Ø1/3 of yellow F2 plants pollinated with pollen from pure breeding green parent had only yellow seed (Yy) Ø2/3 of yellow F2 plants pollinated with pollen from pure breeding green parent had 1/2 green and 1/2 yellow seed 23 Mendels experiments 1 of 2 R. Ward: Spring 2001 Slide 24 of Chapter 1 24 Dihybrid crosses R. Ward: Spring 2001 Slide 25 of Chapter 1 25 Dihybrid cross introduction Monohybrid F1 F2 3 Yellow: 1 Green Di hy br id Cr os s 3 Round: 1 Wrinkled Note: Round/Wrinkled trait is a xenia trait like seed color X Dihybrid F1 R. Ward: Spring 2001 Slide 26 of Chapter 1 26 What progeny will appear in the dihybrid F2? Dihybrid F1 SELF POLLINATION ? •would only ‘parental’ phenotypes occur? •i.e., yellow round and green wrinkled in a 3:1 ratio? •or could ‘recombinants’ occur, i.e., •yellow wrinkled or green round? R. Ward: Spring 2001 Slide 27 of Chapter 1 27 Recombinants did occur in the dihybrid F2 Phenotypes seen in the Pods on dihybrid F1 plants indicates unknown allele R. Ward: Spring 2001 Slide 28 of Chapter 1 •both parental and recombinant phenotypes occurred in the F2 generation Øseeds in pods on selfed F1 dihybrid plants Øgreen round and yellow wrinkled seeds were not present in the parents and are new combinations of the parental traits. We call these ‘recombinant’ phenotypes. •without progeny testing, we don’t know if a yellow seed is homozygous dominant or heterozygous; the same is true for round seeds •to indicate this uncertainty, we represent a dominant phenotype with a the dominant allele symbol (‘Y’ or ‘R’), followed by a dash. The dash indicates that the second allele could be either the dominant or the recessive form. •for recessive phenotypes, we know the genotype (wrinkled is ‘rr’ yy’) 28 Dihybrid Data confirms monohybrid 3:1 416 : 140 3.18 : 1 R. Ward: Spring 2001 Slide 29 of Chapter 1 •Mendel observed the combined phenotype 556 F2 seeds •in the parental classes there were: Ø315 of the parental phenotype with both dominant traits (yellow, round) Ø32 of the parental phenotype with both recessive traits (green, wrinkled) •in the recombinant classes there were: Ø108 of the green, round; and Ø101 of the yellow, wrinkled •grouping the yellows together (ignoring the seed shape trait), there were 416 round seeds •grouping the green seeds together (ignoring the seed shape trait), there were 140 wrinkled seeds Øthis gives a 416: 140 ratio, or a 3.18: 1 ratio, which is the expected ratio for a monohybrid segregation with dominance. 29 Dihybrid Data confirms monohybrid 3:1 (2) 423 : 133 2.97 : 1 R. Ward: Spring 2001 Slide 30 of Chapter 1 •the ratio of round : wrinkled (ignoring the color trait) was also very close to 3 : 1 30 Independent assortment: Mendel’s second law vthe law of segregation applied for both traits vin other words, the two traits segregated independently of each other Ø i.e., green occurred independent of wrinkled even though they were together in the parents vWe say that alleles of these two genes “assort” independently of each other vit would be simpler, and still accurate to say that these two genes “segregate independently” from each other R. Ward: Spring 2001 Slide 31 of Chapter 1 •“Law of independent assortment: during gamete formation, different pairs of alleles segregate independently of each other” (Hartwell et al pg 22) 31 Dihybrids form four kinds of gametes R. Ward: Spring 2001 Slide 32 of Chapter 1 •gametes receive one or the other, but not both types of alleles at a single heterozygous gene •this is true for each gene, so gametes in a dihybrid (considering only the genes of interest), will receive one allele from the color gene, and one from the shape gene. •the law of independent assortment states that this joint distribution occurs such that the allele that a gamete receives for one gene does not influence which allele it receives from a second gene. •Since the probabilities of ‘Y’ and ‘y’ are equal (i.e., both = 0.5), and the same is true for ‘R’ vs. ‘r’, and the segregation for Y/y is independent of R/r, each of the joint outcomes (YR, Yr, yR, yr) each equal 0.5 x 0.5 = 0.25 or ¼. 32 dihybrid punnett R. Ward: Spring 2001 Slide 33 of Chapter 1 •the Punnet square illustrates that there are 16 ways to combine the four types of gametes together in fertilization. Each of these ways has a probability of 1/16. •But there are only 9 genotypes and 4 phenotypes possible 33 dihybrid punnett (2) 1 2 4 5 2 3 5 6 4 5 7 8 5 6 8 9 R. Ward: Spring 2001 ID Geno. cnt 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 YYRR YYRr YYrr YyRR YyRr Yyrr yyRR yyRr yyrr 1 2 1 2 4 2 1 2 1 Slide 34 of Chapter 1 •in this case, each cell in the punnett square has the same probability Øbecause each gamete has an equal probability, and the product of the frequencies of the two gametes combining to make a cell in the punnett square is the frequency of that cell. In this case, all gametes have a probability of 1/4, and all cells in the punnett have a frequency of 1/16 (1/4* 1/4) by the law of the product •There are 4 gametes from a dihybrid. The general formula for the number of gametes is 2n, where n is the number of heterozygous loci in the plant generating the gametes. •There are 9 distinct genotypes (ignoring parental origin of alleles) in the progeny of a dihybrid. The general formula is for the number of genotypes in the progeny of a selfed plant is 3n where n =the number of heterozygous loci. The ratio of genotypes is based on the number of ways that a given F2 genotype can occur. Each of the cells represents a way that a genotype can occur in the F2. If a genotype can occur 2 ways (YYRr, YyRR, Yyrr, yyRr), then its probability is 2 * 1/16 (i.e., 1/16 + 1/16), because of the law of the sum. •In this case we have only 4 phenotypes. 34 Phenotypic frequencies in a dihybrid F2 vY- and R- each have a frequency of 3/4 in the F2. vyy and rr each have a frequency of 1/4 in the F2 vcombinations that are possible (phenotypically) in the F2 are: Ø Y-R- prob= 3/4*3/4= 9/16 Ø Y-rr prob=3/4*1/4=3/16 Ø yyR- prob=1/4*3/4=3/16 Ø yyrr prob=1/4*1/4=1/16 vF2 ratio is then: 9:3:3:1 R. Ward: Spring 2001 Slide 35 of Chapter 1 35 Independence of segregation proved by ratio of the four phenotypes in a dihybrid F2 R. Ward: Spring 2001 Slide 36 of Chapter 1 •product law only works if two events are independent. •If seed color and shape were controlled by a single gene (pleiotropy), then the frequency of Y-R- would have been 3/4, not 9/16. •So independent assortment proven by the presence of recombinants, and the predicted ratios or frequencies based on the law of the product. 36 Mendel used test crosses to confirm genotypic ratios in dihybrid F2s R. Ward: Spring 2001 Slide 37 of Chapter 1 •crosses to a plant that is homozygous recessive at all loci (that you are studying) is called a test cross. •This figure illustrates testcross outcomes for each of the 4 genotypes that produce the Yellow Round phenotype in the F2. Each testcross has a unique outcome, thereby defining the genotype of the tested plant. •Mendel found that the genotypic ratios matched that which was predicted by the law of independent assortment. 37 Summary: Mendel’s Contributions v inferred the existence of genes, units of inheritance the reappearance of ‘hidden’ traits that disappeared in an F1 generation v disproved the theory of blended inheritance v demonstrated that both the male and female parent contribute equally to the next generation v revealed the two basic principles of gene transmission: v explained Ø segregation of each gene’s alleles during gamete formation Ø the independent assortment of alleles of two or more genes R. Ward: Spring 2001 Slide 38 of Chapter 1 38