* Your assessment is very important for improving the workof artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download final report on the alaska traditional diet survey

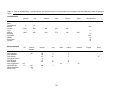

Survey

Document related concepts

Transcript